Interview 054 • Sep 26th 2016

- Interview by Lou Noble, Portrait of Wynn Miller by Emily Van Ness

About Wynn Miller

Wynn Miller’s career has spanned over 30 years, both as an award winning advertising photographer and photojournalist. His late 1970’s work, capturing skateboarder Tony Alva and his fellow Dogtown skateboarders, has achieved iconic status. Miller’s exhibit, Freshjives Mad Dog Chronicles, has traveled the world with showings in Tokyo, Paris, Los Angeles and New York.

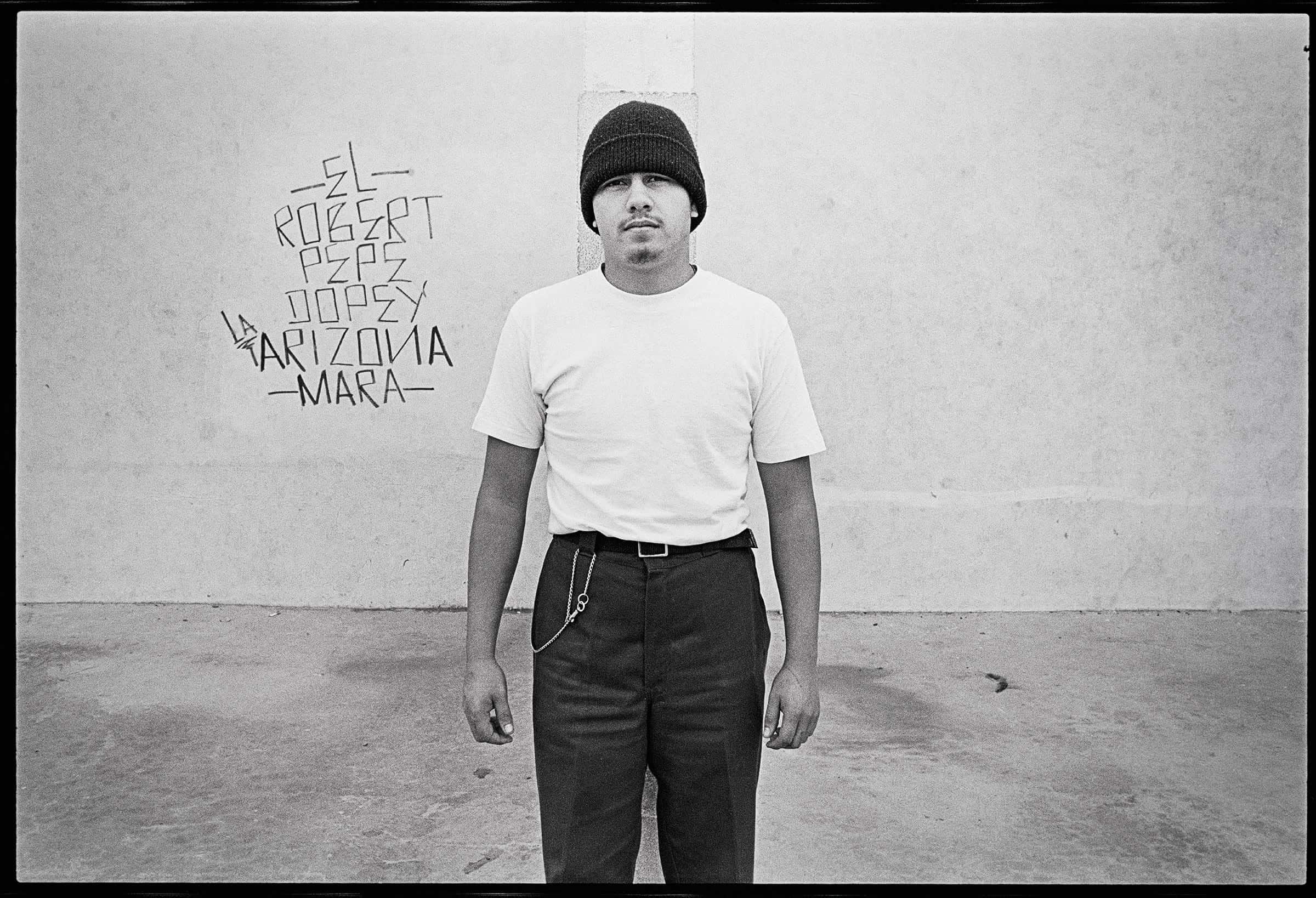

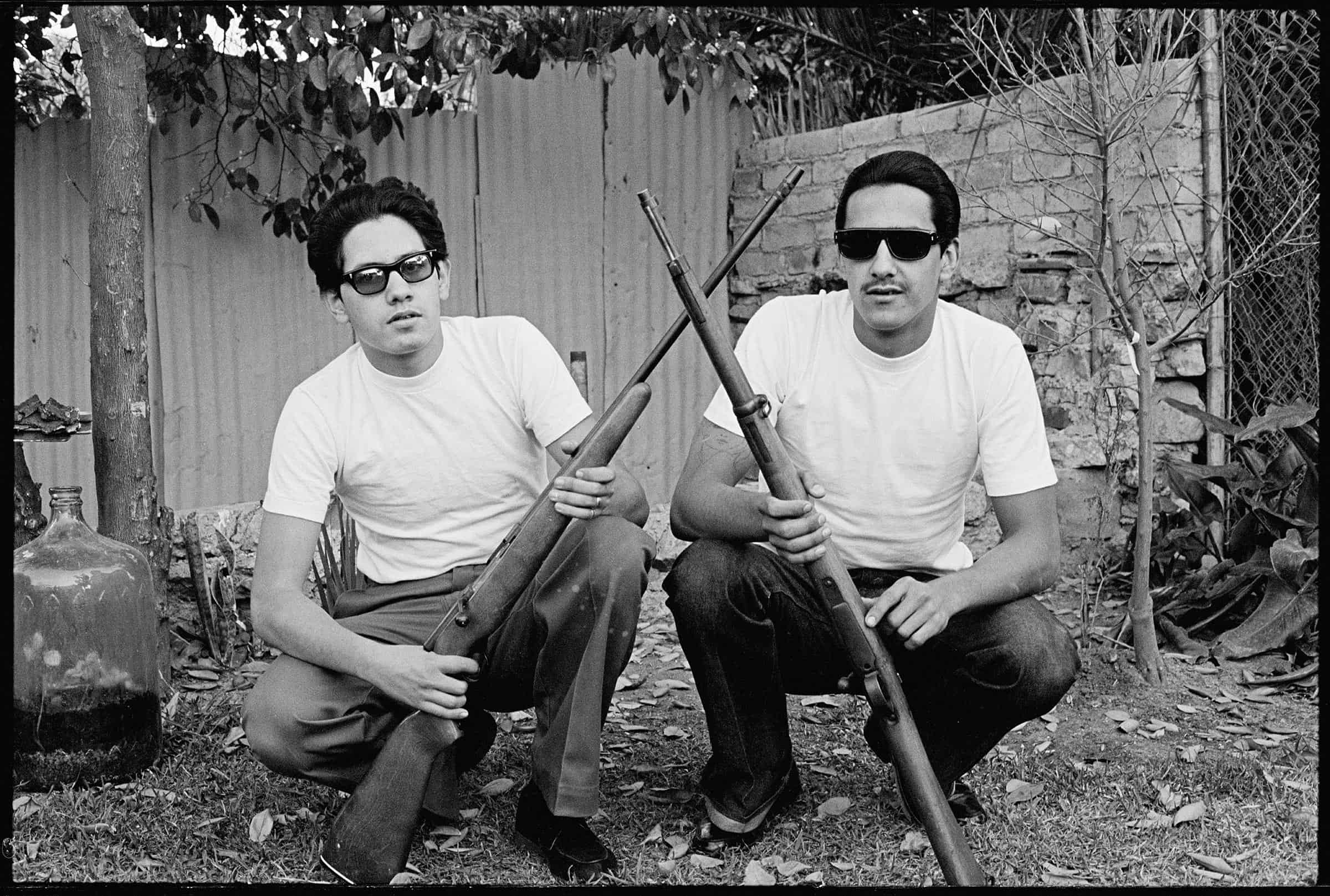

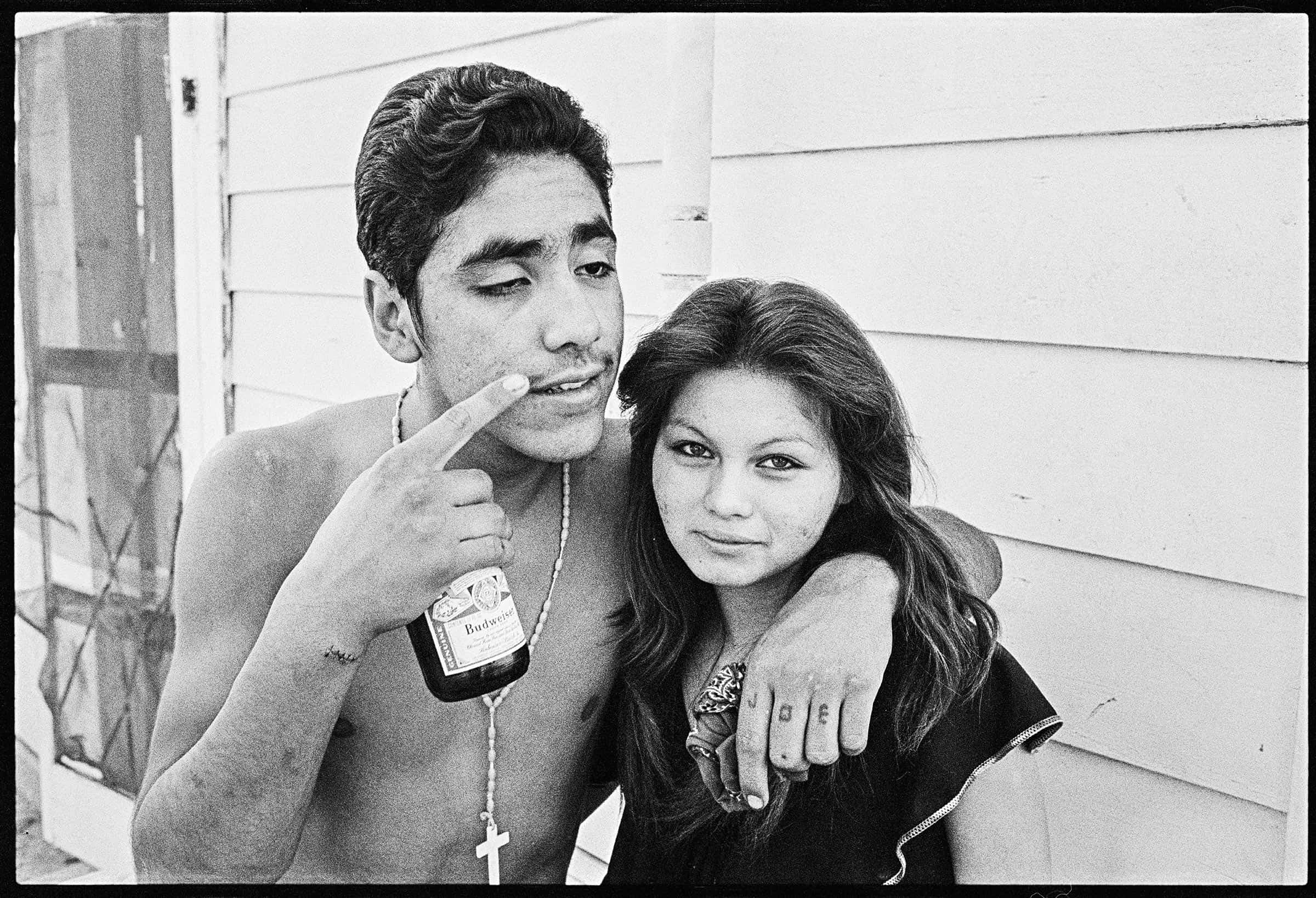

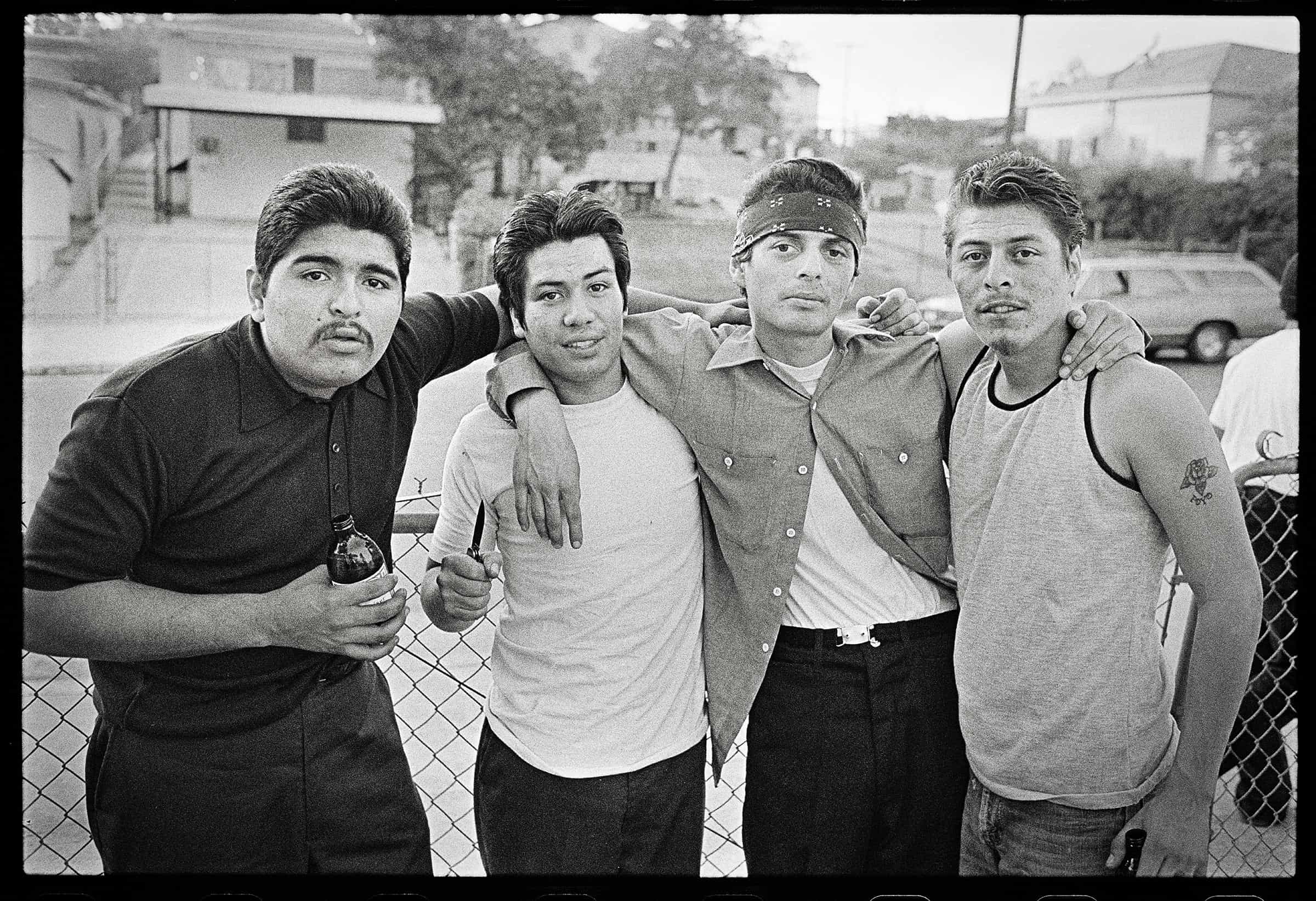

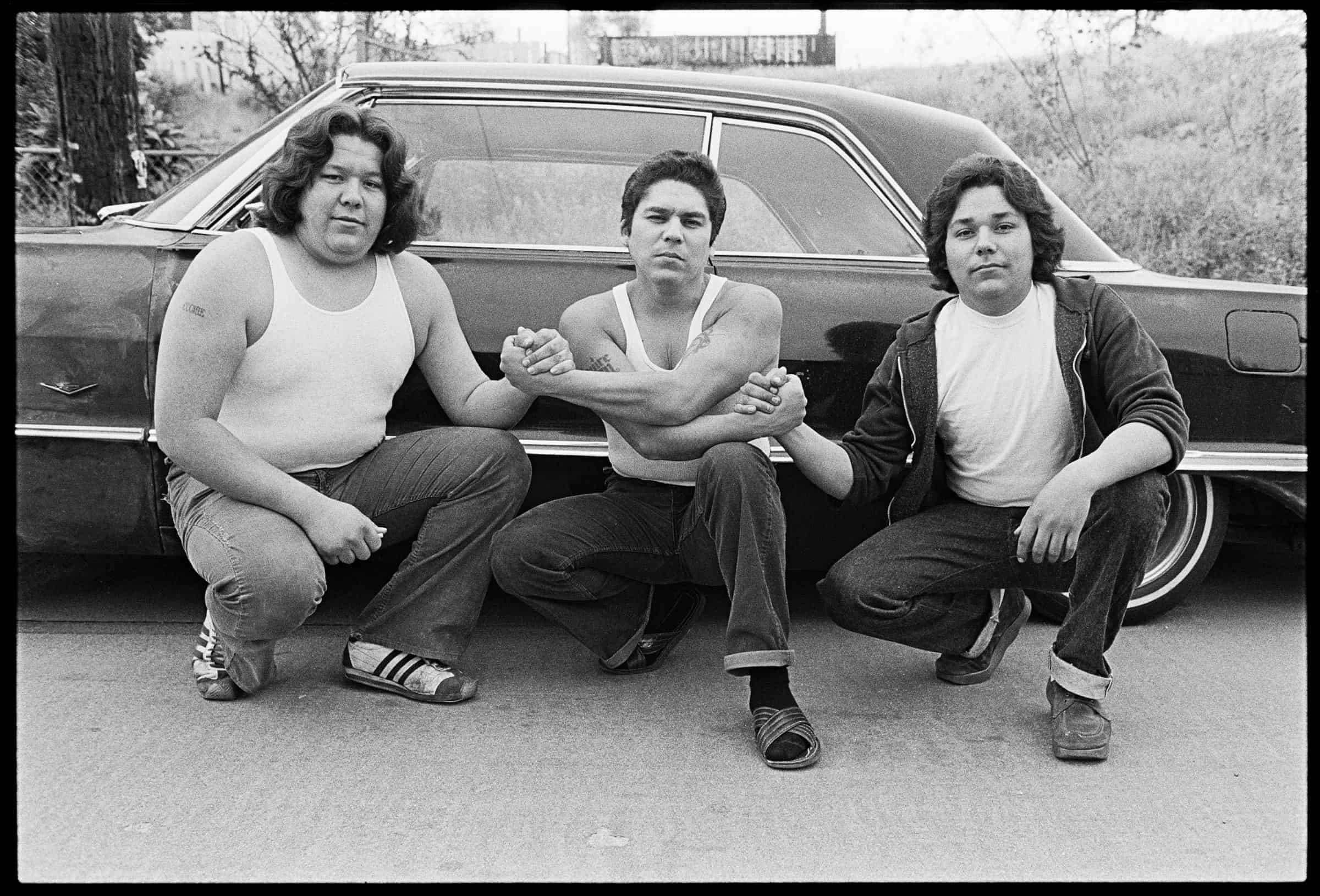

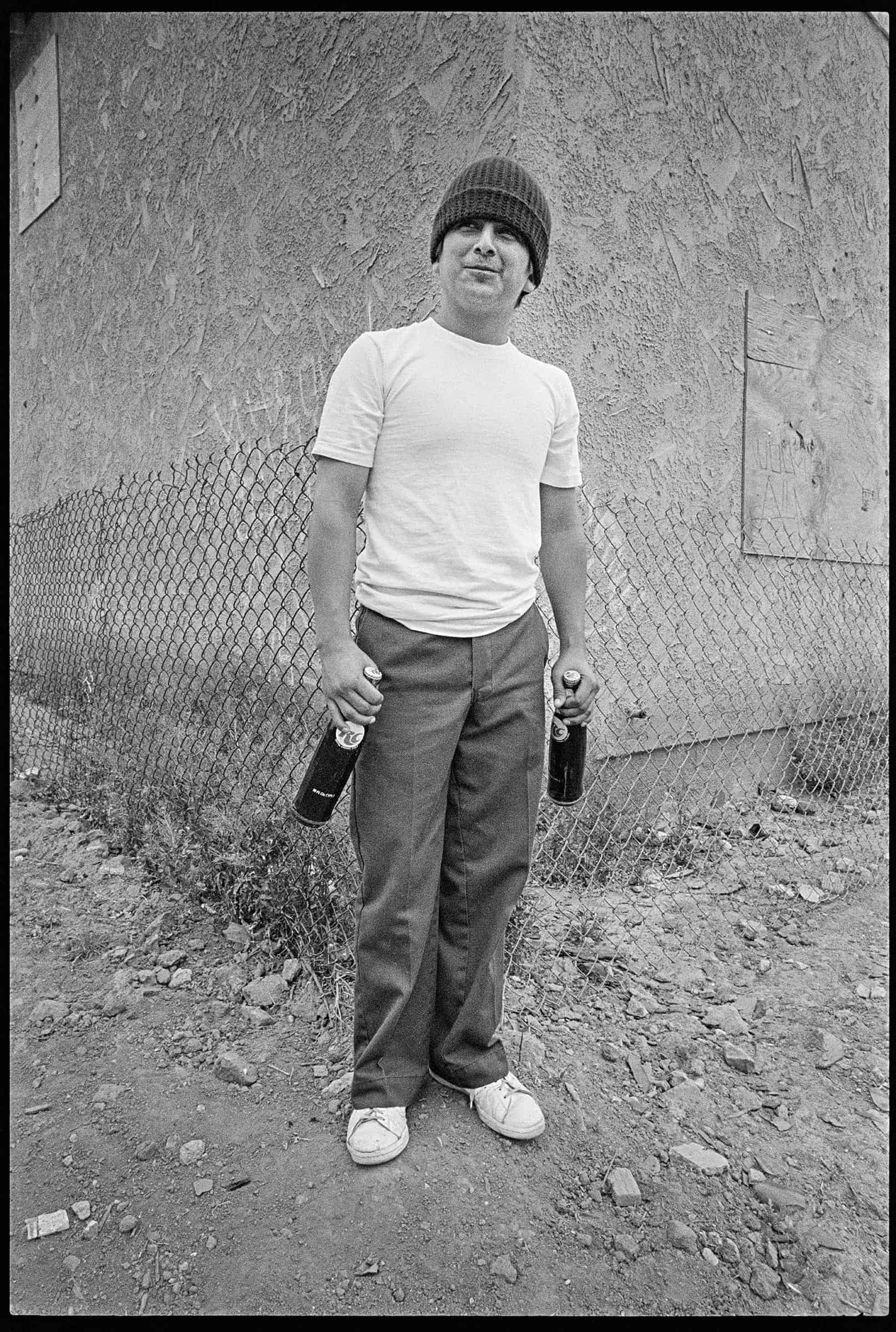

In contrast to his work with Tony Alva in the 70’s, Miller was also documenting a year in the life of an East Los Angeles street gang known as “Arizona Maravilla”. He immersed himself with the crew, earned their trust and was allowed to photograph them on their own turf. This allowed for a previously unheard of level of access.

Miller, a Los Angeles native, studied photography at Santa Monica College and UCLA. He lives happily on the Westside, hanging with his two daughters and teaching his new grandson how to surf.

Links

Foreword

Choices that can affect the rest of your life come up more often than you think. The key lies in recognizing those opportunities, using your best judgement, and taking advantage of them.

Wynn Miller made the most of the opportunities given to him. Let him be an inspiration for your day to day.

- Agustin

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

How did you get started in photography?

Well, even when I was young, I had an interest in film making and photography. When we were in high school, we used to screw around and make movies, little home Super Eight movies with my dad’s camera. And we would tell little stories, mostly about drug deals gone bad.

Ha! You’re from Santa Monica, right?

L.A. I went to Fairfax High School.

Okay, right on.

Yeah, this was at the end of the ‘60s. I graduated high school in ’68 and got into UCLA, which was obviously kind of easy then, if i got in. And I had to go to college because of the Vietnam War. I didn’t want to, but it was either that or serve.

Yeah, good choice.

I really wanted to surf more than anything.

When did you start surfing?

When I was thirteen, so by the time I finished high school, I’d been surfing five or six years. I’d been to Hawaii once and decided I really wanted to go back there. So I was at UCLA. I was a film major for two years but… A) I didn’t want to be there. B) The problem then with the film major was, you didn’t get any hands-on experience the first two years, it was all…

Arizona Maravilla gang series | Wynn Miller

Theory.

Yeah, all theory, all history of cinema, all art history. I mean, there was a good foundation, but I wanted to be doing something and that just didn’t happen. So at the end of the two years, they had the first lottery for the army and I got a great number. I got 306 out of 375 so I…

The lowest numbers went first?

Yeah, if you got picked one, you were going to Vietnam. So I knew there was an almost zero chance they would ever get near 306 so I quit school, packed up a couple of surf boards and moved to Lahaina, in Maui.

Oh, wow.

There were a few other guys I knew that were around. I just wound up staying for three years, and I mean, surfing more than anything. I was trying to see how good I could get.

How’d you support yourself?

I had a variety of jobs. I was a cab driver. I worked at a restaurant, which is what most guys did, work at a restaurant at night, surf during the day. I was a gardener. I worked in a little hotel being, like, a maid, making beds and cleaning up the rooms. I got food stamps at one point. I was poor, but…

But for you it didn’t matter.

No, because I surfed my brains out. Then I sort of realized that I wasn’t really getting good.

Hahahaha!

I’d clawed my way to mediocrity and I stayed right there. It was fun still, just disappointing. It turned out my dad had some property over there and he came over on a trip and had this camera, I think it was called a Fujicarex. it’s obviously not around anymore. He said, “Do you want this camera?” And I go, “Sure.” And he goes, “You’re living in Hawaii, take some pictures.” So I did.

I started to take pictures and started to get that bug. I got that photo bug. And I was lucky enough to meet this guy, another guy like me who just was into it, but he had a darkroom in the back of his house. It was near in the sugar cane fields. And he was cool enough to teach me how to develop film and do basic black and white printing. And then I was hooked, man. I loved printing so much.

Oh, really?

I loved it, and um, counter to that…I started to take some pretty serious drugs. It was a druggie time in the sixties. This would have been around ’71 or ’72 and I could see that I was going in a direction that was…heroin was starting to come into town. I just made the decision, I better get out of here. I’m not going to be a great surfer, photography is interesting. I could get into trouble, and so I just picked up and left and went straight to Santa Monica College. I applied to the Art Center and all those places but, you know, Art Center was so expensive and…

It’s still expensive!

Yeah, you know then it was like ten thousand dollars for four years.

Arizona Maravilla gang series | Wynn Miller

Heh, wow. (Fun fact: Art Center College of Design is now about $19,000 per SEMESTER. Although $10,000 in 1971 was equivalent to about $59,400 in 2016.)

Which was a huge amount of money for me in those days. So I didn’t even bother to ask my dad, I’m sure he would have. I just applied to Santa Monica College. And they had a pretty good department, good enough to where, if you were ambitious, you could get what you needed there, which was what I did. I went there, I graduated, I got an Associate’s Degree and I got along great with one teacher there, Don Battle, he was sort of a mentor and he, I guess he saw that I had some spark and he was always pushing me and, you know, forcing me to go into things I wouldn’t normally do, and you know, like all of us, I read all the photography magazines. And I…and I, uh, I really had a hunger to learn about photography. And that’s what I did for a couple of years and then I started assisting. That was the way to go. Find the best photographer you could and go to work for them.

Was there something in particular, was there one aspect in particular that you were really taken with?

In advertising?

No, when you were learning.

Well, when I was learning, I shot everything. I shot my skateboarding stuff, I shot the the gang stuff.

So that stuff was while you were still…

I was at the tail end of college.

Oh, okay, you were still in school when you were…

Yeah.

Oh wow, okay, I thought you were already…

No.

Arizona Maravilla gang series | Wynn Miller

Oh, okay

Because I actually only went to school for a year and a half and got the AA because I had taken a lot of classes at UCLA.

Right, so you had two years already.

I went backwards really. And, um, yeah. I mean I started shooting. I was shooting stuff in Hawaii, lots of stuff and then I came back and kept shooting and I think I had just finished college at Santa Monica when my brother-in-law told me about the Arizona Maravilla gang.

And that stuff was really just the beginning of you as a fully-formed photographer.

Well, I had gotten paid for one job, I shot Don Cornelius.

Soul Train!

Yeah! The funny thing was it was for, ah, Sepia Magazine. I don’t think it’s around anymore. But it was like Ebony, but it was Sepia.

Ha!

And they thought that the writer and I were black guys because they were like based in New York and they would just send, you know, jobs to us and we never told them, “Hey we’re not…” But, uh, and so I shot Don Cornelius, and that was really my first…No, no, no. You know what my first paycheck was? I forgot. I flew back from Catalina on a seaplane. We used to go back and forth on these seaplanes. And one…

Because your family has a hotel, there.

Yeah, we have…the hotel wasn’t built by then, it was just sort of a property, a smaller property, but yes, we do. And there’s a ramp that came out of the ocean. The seaplane would land in the water and come up the ramp. Well, something happened and the plane fell off the side of the ramp. It’s a little plane, and it was kind of leaning over, it tipped over and I took a picture of it and I thought, “Well this is cool, man, this is…I’m going to do something with this.”

So we got back to town and I drove straight to the LA Times and went to the photo department and said, “Hey, I got a picture of an airplane crash!” And I’ll never forget. He was this old-time hard-ass art photographer and he goes, “Yeah, we’ll see about that, kid. Let me take that” So, I didn’t know they could do this, they ran in, they had some quick developer, they developed it, the guy held it up to the light, said, “Maybe that one,” made a quick print and said “Thanks” and gave me everything back.

Next morning I woke up, front page, LA Times, my picture. Slow day for news, I guess and, but the thing was, I said, you know, when I went and called the guy the next day and said, “How much do I get paid?” He goes, “$75.” And that’s when it clicked in my brain, “Well maybe photojournalism isn’t the way I go and make a living.” Because I’d had my first daughter, Leiana, it was getting up to around baby time and I had to make some money, you know, and assisting didn’t pay that well and I hated being an assistant.

Arizona Maravilla gang series | Wynn Miller

That was 1978 at that point, right?

Yeah, she was born in ’78, and so I kind of made a curve. Don Battle, my teacher, sent me to a couple of places that needed assistants and I caught on at one place, this guy, Gerry Trafficanda up on Hollywood Boulevard. He shot everything. We got along and I worked for him for…I mean I was only an assistant for a year and a half, I just…And I worked at this place in the marina called Lenny Inc. where they used to produce catalogs. And that was all four by five.

I was grateful that I learned how to use those cameras in college, so I started to work there, it was seasonal work. Me and this other guy, there was this empty space across the parking lot from the place where we were working and went over there and decided, “This is going to be our studio.” Three of us got together and put up the money and built a studio right in Maria Del Rey. That building’s no longer…It’s gone, it’s an apartment building.

But that’s pretty much how things got started and then it’s a matter of, you know, I shot Lenny, and then because of my skateboarding pictures, somebody called me and said, “Hey, we like your pictures,” and it was the weirdest thing. The guy called me and said, you know, “I like your work in skateboarding I work for a skateboard company in Santa Cruz and we need some work done”, and he came down and just…I didn’t have my studio yet, I was renting a little one, and he brought this other guy who had a business…in any event, I met those two guys and they were responsible for the next thirty years of almost everything, in one way or another, every job that I got.

Holy shit.

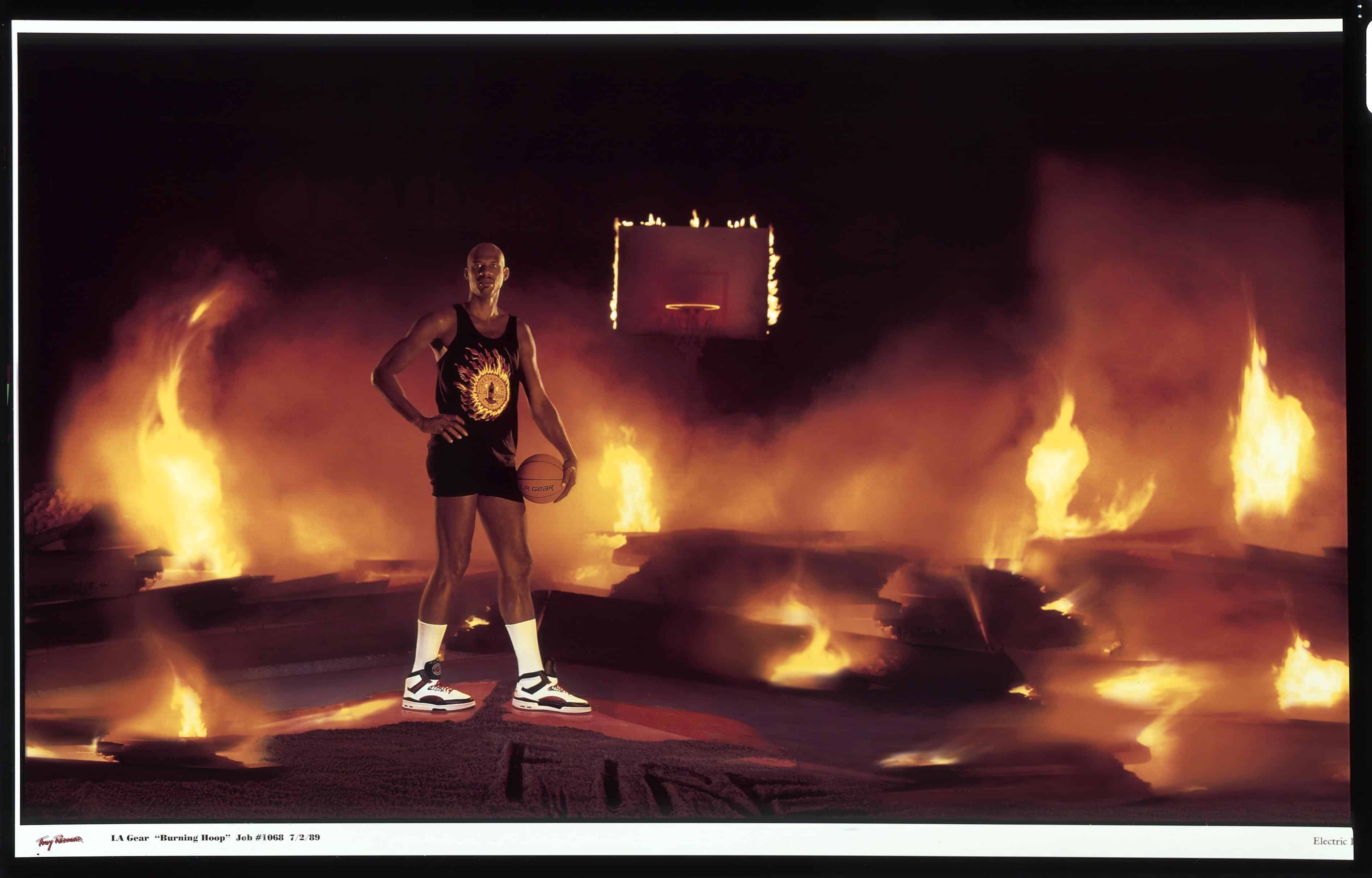

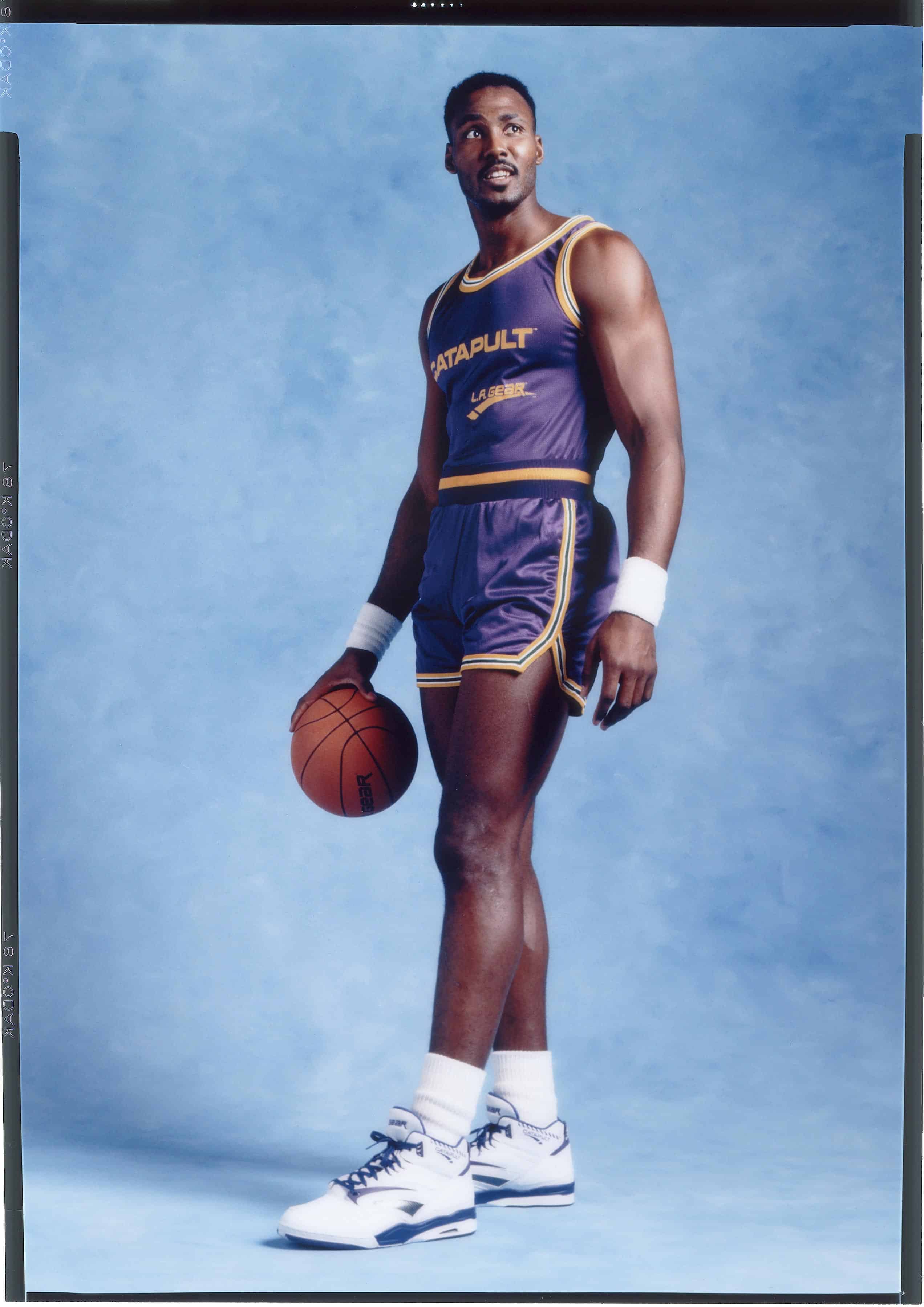

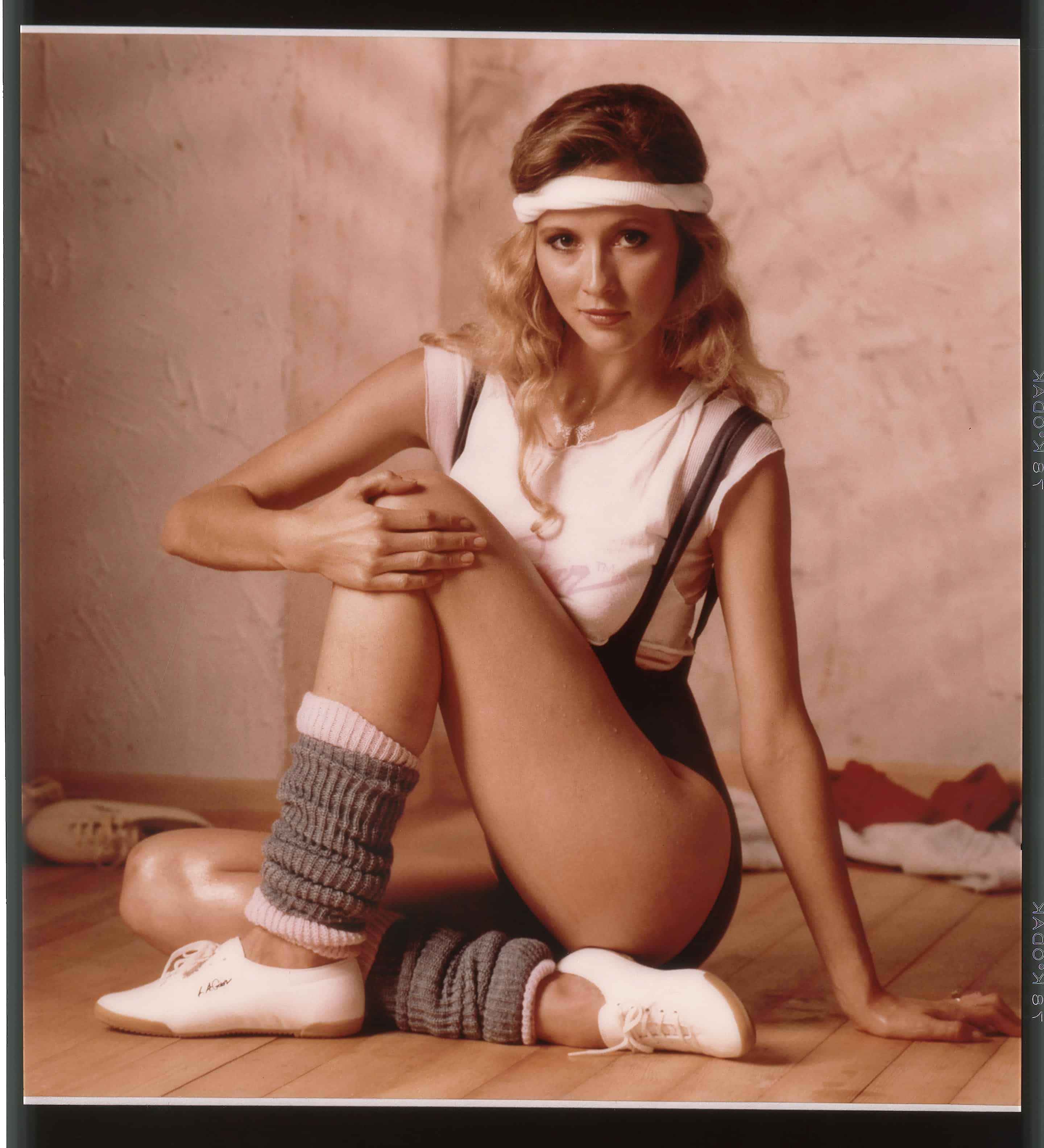

Yeah, it was so fortuitous to meet them, because one guy had helmets, skateboard helmets and elbow pads. And then one day, he said, “Hey I’ve go these shoes. We’ve got this new thing we’re doing. We need some pictures.” And I said, “What’s it called?” He said, “L.A. Gear.” And it turned into the L.A. Gear which was like, at one point it was the fastest growing company in history. It was crazy.

Yeah, they were selling all kinds of stuff.

Oh yea, and so I did all their photography for many years and then they slowly but surely went out of business, like most entrepreneurs do when they don’t know business, but they know ideas.

Yeah.

And I met a couple of guys there who went on, one guy went on to work for a company called American Sporting Goods which became another huge client and so it was sorta word of mouth and being in the right place at the right time that I got my studio up and running. I wasn’t…at that point I was concentrated on making a living. That was my main goal and advertising paid the most. And I sort of, I didn’t give up, but my journalism career went dormant and pretty much stayed dormant until thirty years later there was all this excitement about skateboarding again and they were making a movie about it and I said, “Well…” They found me and the pictures started going. We had an art exhibit that we took around the world. It was fun.

So when you were doing the gang stuff it was because you were interested in photojournalism.

Yea, I really thought… You know I used to love Henri Cartier-Bresson and “The Americans?” Great photography book. Robert Frank…Great photographer. Those guys turned me on. Irving Penn was my favorite photographer in the world because he could do everything. I really admired that about him and I sort of said, “well, would like to be able to shoot anything, too.”

Arizona Maravilla gang series | Wynn Miller

That’s what your portfolio looks like. I mean that’s what your portfolio looks like today. It’s super-versatile.

Yeah, which isn’t always necessarily a good thing, because a lot of times people are looking for a specialist. Food photographer, car photographer, fashion photographer. You know, Then it even gets into subcategories.

More specialized.

Yeah, they only shoot pizzas. Or, you know, they only do beer. There’s guys who do beer-pouring and stuff. That’s their specialty.

Fast food.

Yea, so, I never specialized in anything. I just took what came my way. I wasn’t even picky. Every job was my last job so I would take the next one that came along.

What was it that you found really fascinating about the gang, when you were hanging out? How long did you hang out with them?

Well, on and off for a year. But, you know, I probably never spent two days in a row there. And some days I’d go there and there’s nobody around and there’s nothing to do and I’d leave and I still had work I was doing. You know, I was assisting and setting up our studio, but then a couple of guys got killed. I couldn’t end up…stuff had been published already.

So you were doing the documentary stuff on the side.

Anyway, the stuff was getting published around and I started to think that I was exploiting these guys and it wasn’t really, you know, for the shock value.

Right.

And then this one kid. This little kid that I had kind of made…you know, we were buddies got shot one week walking down the street when I wasn’t there. The guys told me when I came back. And then I just…

Plus, you know, I got shot at a couple of times when I was there.

Really?

I didn’t tell my wife or anything. Not directly, but someone took a shot at us while we were hanging around in the group. And another time, one of the guys I was with was drunk holding his rifle and he dropped it and it fired, and I just figured…

It’s getting a little too heavy.

Yeah, you know, I said what I wanted to say.

When did you meet your wife?

Oh, well we were friends, you know, I’d known her a long time. Yeah, she was just one of the crowd we would hang out with. We got together in around ’75. Yeah, but I’d known her for a while.

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller

And so, then, another photographer hooked you up with Tony Alva?

Yea, Ray Flores and Rudy Manheim were friends of mine.

Why didn’t they shoot?

They weren’t…they were just…well, actually, Rudy did shoot Tony, and, you know, he just wasn’t really trained. He didn’t have any…he was just a guy that would go out with his camera and take pictures.

So, you didn’t have any sports experience or…You just knew that you had training, and so you…

Yea, I just looked at it as adverting assignments and Tony was what I was selling. You know.And you met them just by going there.

Going to a pool and seeing them, yeah. And then once I showed Tony the pictures he thought that they were good and he just started calling me and saying, “I’m going to be here this day” and “I’m going to be there.” And around, let’s see, ’78, when Leiana was born, like a month or two later Tony has started his own skateboard company. We went to Europe together and uh…

Was he paying you?

No, I didn’t get paid.

Oh, wow.

I mean they paid for everything. But as soon as I got back, I immediately sold pictures. I did a story, wrote a story. Yeah, it wasn’t big money. I mean, I…that was another reason I wanted to head towards advertising, you know, because I could do these editorial jobs which were more fun really, but just not enough money.

Yea, and you were already…thirty.

I was born in 50.

Ah, ok, so you were in your twenties.

Yea, I was in my mid-twenties.

Yeah.

Mid-to-late twenties. It was funny, I shot Alva a lot, intensely, for a short period of time and then punk started to come in and they all went Punk in around ’88 or something and I couldn’t stand it. It was so, you know, they were beating people up and a lot of the guys went fully punk.

Kind of thuggish.

Yea, you know, leather and black hair and they literally beat someone to death, a couple of skaters in Hollywood. It just went from, I mean, it got ugly. So I just carried on with my stuff. I would shoot Tony if he asked me to for ads and stuff along the way. I always kept in touch. But then everything sort of died down. And then this guy Rick Clots, you know Fresh Jive?

Mhmm, totally.

Yea, they’re gone now, unfortunately. He’s the founder and creator. He called me up and said…And I didn’t really know him. He said, “I want to put together an exhibit of Tony’s skating photos. Because I’ve been looking at your photos my whole life.” So we did. We put together a show called The Mad Dog Chronicles. The first time we showed it was in downtown.

Yea, so we did a show there and they printed up a little book and, uh, we went and showed in Tokyo. We showed…and the best was New York though, right? And Soho in a really cool gallery, that was my favorite, and it was packed with people and it was New York and it was just cool.

Really vibrant.

Yeah, it was fun.

What was it you enjoyed about shooting the skateboarding stuff? Or was it more like work?

No, no, no, I enjoyed it. Because I knew I was doing something nobody else was doing and when I shot something I was almost sure it was almost always got published. But the other guys, you know, they were kids. They didn’t have the experience I did, so they didn’t know, you know, the idea of bringing a separate strobe system and hanging it over the camera. They didn’t know how to do it, so they did what they could do and, you know, they were some pretty good photographers.

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller

But you had experience on your side.

Yeah, I just tried to make him look different. I kinda wanted to make Tony look more heroic. I never wanted to show him with a bunch of other people. I was shooting him by himself, if I could. And, um, yeah it was fun.

Did you find it a big challenge, creatively?

No, not really. It wasn’t too hard to come up with ideas. Because, I mean, it could be as simple as putting, you know, a mask on him. And let him skate with a mask. A lot of it was lighting, too.

It was just different from what everyone else was taking.

Yeah. Pretty much all the kids used the same lens, a 16mm fisheye. That was the lens.

Makes sense.

Because you could get really close. And a lot of times you’d go to the park and you’d have to find your spot, where to shoot him. I would go and say, “Tony, that’s where we’re you’re gonna be…that’s where we’re doing the shot.” We’d do it ten…however many times until we knew we got it. If you just went down there and shot like most kids do, or did, in those days, the odds of getting a really good shot weren’t that high because you were trying to figure out what they were going to do. Well, I already knew what they were going to do, because I told them what to do.

You had a lot of control over the shots.

Yea, but everyone wanted me to shoot them. They were all, you know, “Wynn, when are you going to shoot me?” But I sort of realized I was just going to shoot Tony early on. So I’d shoot the other guys so there’d be something, but I really concentrated on Tony.

Why did you choose him?

A) he was the most interesting guy. B) he was the best skateboarder in the world, at the time. C) nobody had the charisma or the, you know…

He was a lot more photogenic.

He was photogenic. He got famous pretty quickly. He was, you know, pretty arrogant in those days. Got in fights and stuff pretty regularly. He was an interesting guy to me. Plus, we were both surfers, so we got that. We shared that.

Yea, because there’s more to bond with.

We became buddies. We traveled around, we had to share rooms together, you know.

And you were a few years older than him.

Yeah. But, you know, I was a kid at heart. I skateboarded when I was young. I mean everyone knows what it feels like to get on a skateboard. Whether you only did it one time or did it for a while. I think that skateboarding is something a lot of people can relate to. Maybe not the stunt work they’re doing now, but…

And so, it was simple for you to really, I mean, it was simple for you to make those shots because…

It wasn’t simple, I mean, you know, I had sometimes two or three lights set up around the pool. And, in those days we were shooting transparency film. The black and white was all tri-x. The color stuff was all done on slides.

Oh, wow.

Yea, it was long before digital. It wasn’t even…transparency film is much harder to shoot. Kodachrome or E6 as we call it. Ektachrome.

And then, ah, so when you came back from the European trip is when you decided and you saw how…

First of all, my wife, Toni, was pissed as hell that I left. Leiana was only three months old.

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller

How’d you sell that to her?

I said, “Toni, it’s a once in a lifetime opportunity. I may never get to do something like this again. I promise I’ll make it up to you somehow.” And she…I mean to this day she still has a little anger about it. A little bit.

So when to came back you decided to do advertising stuff.

Well I decided that I was going to have a studio and do whatever I could, you know? And then a guy I knew came to me, said, “Oh, we’re doing this show for Max Factor, you know, can you help us out?” So the lady from Max Factor came and we worked together on the shoot and she just started giving me work. From then on. For years and years and years.

For a variety of companies?

No, for Max Factor.

Oh, for Max Factor.

Yea, so I had a few pretty big clients.

Did you…you had really been into photography just as a fun thing. Did you still shoot other than the advertising stuff or were you doing it just for work at that point?

I pretty much just shot. It was a lot of work, you know, I got busy. And I shot my kids. No, no I didn’t shoot anything other than what almost anyone would shoot with a growing family.

Kareem Abdul Jabbar for LA Gear | Wynn Miller

I’ve got a bunch of friends who are just starting to become successful in photography and a lot if them are starting to struggle with it, “Oh, but I want to shoot my own stuff. But I’m so busy.” Or, “When I come home I don’t want to shoot…”

Oh, I would come home and print because I loved printing. But I didn’t, I didn’t have that dilemma. I was just happy to be workng and to me Irving Penn was the God that I would aim for. So, if I got to shoot, you know, shoot people or, you know, he shot cigarette butts. Um, no, I don’t remember any great conflict about it.

I mean, did you enjoy he advertising work?

Yeah! Oh yeah. I loved taking pictures. I still do. I still can’t believe I get paid to take pictures. So I don’t, you know, it’s mundane, a lot of it, but it’s still taking pictures. It’s not like an assembly line, I mean, it can feel like that at times but…

But for the most part you enjoy it. I guess my assumption was the advertising work wouldn’t be fun.

Oh no. No, I got to travel. There was a period where I was working…back in the day, you know in corporate meetings now they have these videos…well they used to do it with slide projectors. There would be 4×5 projectors so there would be twenty projectors in a grid and you would time them and pictures would come and go. That’s how they did it then. And it required a lot of materials so the would send me. I’ve been to 25 out of 50 states shooting for those guys. Shooting for slideshows. Corporate work.

Oh, wow.

And, you know, then when I worked for L.A. Gear they shot celebrities, so I got to shoot pretty famous people fairly often. I shot Michael Jackson. Which was really interesting because I wasn’t allowed to talk to him!

L.A. Gear paid him a chunk of money to represent them and be their, you know, their guy to do commercials with. It didn’t work out, though. They needed some still shots of him in various backgrounds with different outfits and different shoes.

After Thriller?

Yeah, I mean, he was huge. And they go, “Well, the way we’re gonna do this is, you set up the backgrounds and you light him. We’ll have someone stand in for the lighting and then Michael Jackson will come in and he’ll know what he’s gonna do, so please don’t talk to him.” So he’d come in and he’d just hit the marks and I’d fire. I mean it was easy! I just couldn’t say anything. I mean I would go, “That’s nice, oh, that’s good.” But I couldn’t say…walk over and say, “Hi Michael.”

You’d throw out some compliments at him.

Yeah, but it was very controlled.

Karl Malone and Advertising for LA Gear | Wynn Miller

Wow.

Yeah, and I shot Paula Abdul for them. Karl Malone and Kareem Abdul Jabar, Belinda Carlyle. Anyway, so it was fun. It wasn’t drudgery being an advertising photographer. The budgets were good and I got to shoot models and I made a couple of really good girlfriends from that.

Did you have any preference of what you liked to shoot?

As long as I didn’t have to do the same thing day after day after day, I was happy. Thirty years flew by like nothing.

That’s crazy.

Yeah, it was good.

I mean are you still working right now? Or have you pretty much…

Yea, I’m sort of semi, half-ass retired. If someone brings me a job I’ll do it. But my biggest client for the last twenty years is a guy that I met originally at L.A. Gear who worked for American Sporting Goods. And just in the last six months they’ve been sold and sort of moved and dissolved, that work dried up. Although I just found out they have a shoe catalog they want me to shoot in the next few weeks, so I’ll be back shooting.

Having the benefit of decades of experience, what are like the biggest changes you’ve seen out of photography?

Well, obviously digital is the biggest by far.

Did you have any…

I didn’t want to do it at first. I still don’t…I’m still not…I have a digital assistant. Yeah, I just…I don’t want to do that, you know, Photoshop. I don’t want to do that stuff afterwards.

So you’ve got somebody who handles all your post processing.

Oh yeah. Absolutely. Martin Herbst. He’s worked for me for 15 or 20 years.

Oh wow.

He’s a great retoucher. He’s a great photographer. He’s, you know, he can do most of the shit I do. Andhe really gets how things work. Like he can get a new application and just plug it in and figure out.

Just know it?

Yea, without even reading the books or don’t the tutorial or anything and I’m still lost.

Right.

It’s a lot of information and it’s a lot of…you have to have a certain way of looking and thinking and I don’t think I have it. Maybe I’m too old, I don’t know. You know I shoot digital and I have for a long time and we do good work, but a lot of that credit goes to Martin.

We started pretty early trying to use digital and, you know, it was crappy. It was really bad. The way that it changed things, to me, is when I was in my prime, photographers were the gods. An art director could come to me and go, you know, “Wynn, I need a shot of an apple floating in the sky with white fluffy clouds all around it.” And I’d have to figure out a way to do that. You know, I’d get a big sheet of glass. I’d put whipped cream, I hung the apple where it needed to be, so I did the shot. Now, the art director comes in, “Well, just shoot me an apple, just shoot me some clouds, you know, we’ll fix it later.” So then the photographers…you become just another tool in the art director’s toolbox. “That’s where I’m going to get the apple shot,” instead of challenging the photographer, you know, to make something happen.

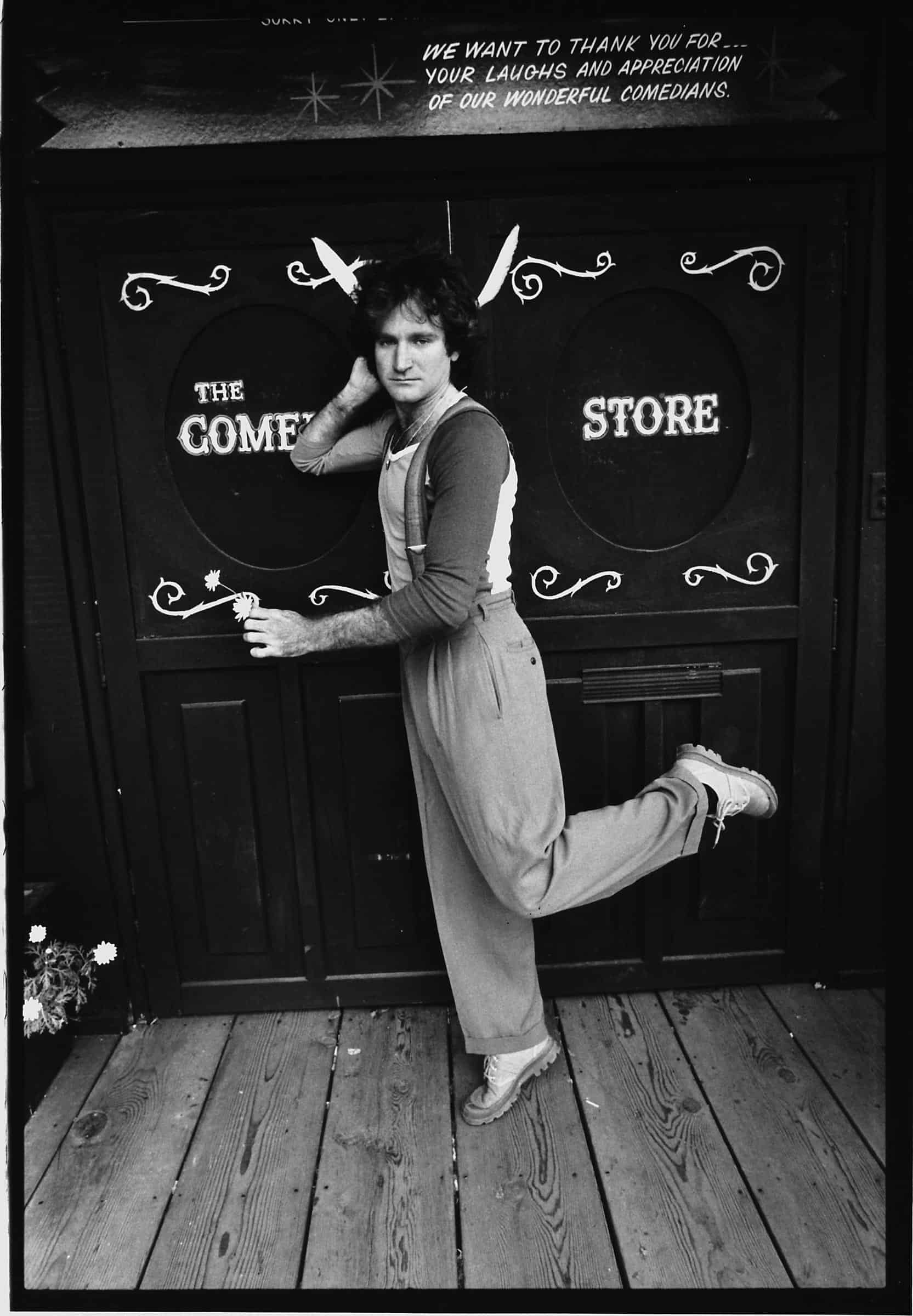

Robin Williams | Wynn Miller

There was a documentary called “Side by Side” that came out a few years ago. It was narrated by Keanu Reeves. He would interview directors and cinematographers about the switch from film to digital and cinematographers said the exact same thing. That like…

That they lost…

That they were the gods because no one could, you wouldn’t know until you got it back.

Right.

The director would ask, “Is it Too dark?” And they’d know, “No, no, no. It’s gonna be good. You’ll see.” But they just had to trust them.

That’s totally exactly correct.

Whereas now, you can see it on the monitor…

Yea, it’s a whole…even the way people shoot now. This is now people shoot. And then they look down. Then they take a picture. Then they look at their camera. I mean it’s all, physically…

Yea, the process of shooting…

Right. The actual process has physically changed. And, you know, I shot a lot of stuff large format. Now they don’t…two and a quarter is plenty resolution-wise, now. I’m sure there’s guys that shoot cars and stuff maybe with a 4×5 but, um, you know. You can do a lot of stuff on 35 that you couldn’t get away with back in the day.

Because of the resolution.

Yea, because they keep improving the chips. And, you know, that’s the other thing, the amount of money you have to spend on equipment now.

Is a lot higher?

Yea, I mean, my Synar’s 25 years old and it’s still a great, perfect camera. But like, you know, your digital camera from ten years ago is totally obsolete. It’s worthless, essentially. And also the big thing now is storage.

Yeah, you need to have bigger cards.

Bigger cards. And, you know, external hard drives. And now they’re starting to use tape I think for storage. But nobody really knows how long these CDs are gonna last.

That’s the thing.

I’m going to have to take my hard drives out every five years and run them for half an hour? I mean, I dunno.

Or just replace them with different drives because…

Yeah or copy everything…

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller

They have different formats. Solid state. Flash drives.

Plus I do a lot of photo shoots by phone now or email.

Do it here and you just transfer it over?

Shoot it here, transfer to my…I have a client in Santa Barbara, and, you know, it slows things down, but it works. I’m shooting, and I call her. I go, “look at your email.” And she’ll look at it and make the correction. And it goes back and forth. I mean, It’s a little cumbersome, but a lot of the clients are comfortable doing it because they don’t have to…a lot of times they want to come to the shoot, if it’s an interesting subject, but if it’s just your essential basic still or something, they’re happy to do it that way because they know they have it the day of, which they would anyway if they were here, but it’s already there.

Have you found that in that way digital is more convenient? Or would you not have cared if you had to develop it and send it to them?

I miss the excitement of not knowing what your film’s gonna look like and having to wait until the lab opens the next day. And then the guy delivers it and you finally get it and you look at it on a light table. That feeling’s gone. You don’t get that from looking at a digital picture on a screen. That excitement isn’t quite, you know, when you’re done shooting a job now, you’re really done. You’re not waiting for two days. They’re not sending it back to you saying, “Can you scan this?” Or make a dye transfer and retouch the dye transfer. Now everyone’s a photographer. Everyone’s a surfer and everyone’s a photographer. We were just at the beach this morning and there were ten guys giving surf lessons on the soft tops, which I don’t mind. I like riding them. They’re fun. Yeah, anyway.

How does that feel, for it to be so much more ubiquitous?

What can I do, you know? I mean, I feel lucky that I had the time that I did. You know, when I started surfing we didn’t have leashes. I lived in Hawaii. I could surf Honolulu Bay with ten guys out. Now there’s 100 guys out. The equipment’s better today, that’s for sure. You could say that about photography and surfing.

Is there anything you like more about shooting digital?

Yea! The same things that I don’t like about it. The immediacy. I know I don’t have to worry. There’s this fine line between anticipating and worrying.

Right

You know. How the film’s gonna look. Especially…you know, we shot Polaroids of everything, especially 8×10 Polaroids, but still… Holding that transparency up is a…it’s a good feeling.

Yeah.

Plus digital, there’s so many things you can do in post that it’s fantastic.

It it frees you up a little bit? From the worry of like, “Did we get it?”

The thing that I hear the most is, “We’ll fix it later. Don’t worry.” But that’s not really the same as, “That’s a really great shot. Thank you for putting it together.”

Do you find that it’s, like, not as enjoyable when you’re shooting, like, now that you’re shooting professionally? Or now that you’re shooting digital rather than film.

No, for certain things, digital’s fantastic. For a lot of things it makes sense. In fact I don’t have any reason I’d ever shoot film again other than…

Professionally.

Yea, it’ll come around. You know, and it will be, “Here’s this interesting thing we used to do. You see these little canisters?” You know…

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller

This used to hold film.

You know, and it’s changes a lot. All the labs I used to use most of them went out of business because they weren’t needed.

There was no business.

They weren’t needed and they didn’t figure out a way to come up with something to replace dipping and dunking film. Some labs, you know…

Yea, there’s still a few labs around.

Sure, you can get stuff scanned. You can get retouching. You can get really nice prints these days. But, it’s like are they photos or are they illustrations? It’s like when OJ’s Bruno Magli shoes. Remember that?

…No?

He was wearing… Bruno Magli is a designer… and they were trying to say that he had a pair of them in his closet that matched. And somebody retouched them into the photo. There was retouching done.

Ohhhhhhh. (Editor’s note: We’ve since watched OJ in America, and know all about OJ’s attempts to deny he owned those shoes. GO WATCH IT, IT IS ESSENTIAL)

Did you ever develop stuff at home?

I always had a darkroom. Especially in my younger days. I had a darkroom at my parent’s house and I had one in the next, we moved around a fair amount, me and Toni when we were younger. One, two, three, you know, maybe three apartments. Close off one of the bathrooms. I loved printing.

When did you stop printing?

When printing stopped. You know, when digital came. Printing for myself was more…You know, I printed those gang pictures. It took a lot of work and it was technical in some ways.

Yeah.

But not like it is now.

Not like working through Photoshop.

No. No, I kind of miss it. But I, you know, I volunteered Venice arts, which is a…you know about it? I work as a mentor there. And we have a darkroom. And we still teach the kids, some kids are really interested in printing.

Yeah.

They all develop their own film when we shoot black and white.

That’s awesome.

Yeah.

I don’t think I’ve developed my own film since high school.

I can’t remember when I did either.

It might have been the same amount of time!

Probably. Probably.

And that should do it! Thank you so much!

Thank you!

Tony Alva | Wynn Miller