Interview 046 • Jun 15th 2016

- Interview and Portraits of Chris Buck by Lou Noble

About Uneasy – 30 Years of Chris Buck

Chris Buck is a photographer based in New York and Los Angeles. His clients include Google, Xerox, Old Spice, Dodge, GQ, The New Yorker and The Guardian Weekend. He has won many awards, including being the first recipient of the Arnold Newman Portrait Prize in 2007. His first book, Presence, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2012. Chris takes his martinis dry, with a twist.

Our first interview with Chris was published Sep 9, 2014.

Links

Foreword

Our second interview follows up with the inimitable Chris Buck promoting his first Kickstarter project. ‘Uneasy’ is a book of Chris’ portraits, with 338 color and black-and-white photographs, from 1986 to 2016. For three decades Buck has been carving out a unique space in the world of celebrity portraiture, capturing its ineffability - its danger, its oddness, its warped sense of reality.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

For more details and backing options on ‘Uneasy’ visit Chris’s Kickstarter Page

⁂

So why a Kickstarter for the book?

I got an email from my mom, and all it said was “Not sure I understand? Are you asking people for cash?” To her generation the idea of asking people for money is, well, rude.

Yeah, it’s unseemly.

But over the past few years I’ve contributed to a few Kickstarters and I was happy to do so (usually it was a friend with a movie or charitable project). In fact I was always a pleased to be invited to participate, so I tried to bring that spirit in planning to crowd source.

And of course the Kickstarter is great for gauging interest, so if I end up selling 200-400 books in the Kickstarter, then I’m going to do a run of 2,000, for example. Also, I recognize that individuals want to support projects from people they like, projects they believe in, and just things they’re excited to be a part of.

When you release it in the fall how are you going to sell it? Will you sell it through your website?

Well, here’s the plan: I’ll reach out on social media again. “Hey, the books are here if you’re interested,” and all that. And I’ll do publicity; press and media, and hopefully that will lead to sales, which would go through the fulfillment house.

I guess I’ll also do some talks and book signings in New York, and elsewhere.

I know it sounds really weird, but selling the book is not my priority. Because my reason for doing the book is not to be “successful.” My goal is to not have the book put me in the hole. But I’d rather not make as much money on the Kickstarter and get some great publicity. I want the book to exist in the public realm. I want to be covered by a traditional, legitimate press, so it exists in the public consciousness in some way. I think that’s why people go with traditional publishers often, is because it feels more legitimate.

1. Steve Carell – Photographed by Chris Buck

2. David Cross – Photographed by Chris Buck

That’s the big thing, the question of legitimacy.

Between my reputation and the people who are in the photographs, I don’t think anyone’s going to look at this and think, “Pffh, modest vanity project.” It’s hundreds and hundreds of pictures, and the stories and great design, everything about it’s going to use the self-publishing thing as a positive. “This book is so special that no publisher would do this.”

Ha!

Taking advantage of self-publishing and making it really big and actually less expensive. That’s a big plus.

Right, lean into it.

If you cut out the middleman, you can shave off about 25% of the price, as a retail price.

I realized I don’t care if it’s done by a big publisher. I do care, but not that much. So why am I going to spend all that money just because it’s what’s done or expected? So I ran into a photographer at a party, Ron Haviv.

We’ve interviewed him!

I wanted to talk to him about a personal project I’m working on, because I wanted to get any tips on it, and I prefaced it by talking to him about Uneasy, and he started asking me questions about it. So he said, “You’re doing it with (name of the publishing company)…why?” And I said, “How else would I do it?”

“Well, you know these days designers can connect you with printers. You can have access to that the way couldn’t have 10-15-20 years ago.”

“I’ll introduce you to my people,” he said. The next day, I emailed him, and he responded within a couple of hours giving me all the details of his people. I called de.MO and sent them the website for the project and they said, “We’d love to do this.” And that’s what I’m doing. It’s crazy!

And it’s totally scary; I guess that’s why the Kickstarter’s so important. For me to find the level of interest, both in terms of people supporting the project but also wanting the book, it makes me feel better going forward in this sort of mysterious land.

What kind of thoughts went through your head as you were going through those photos to make the book?

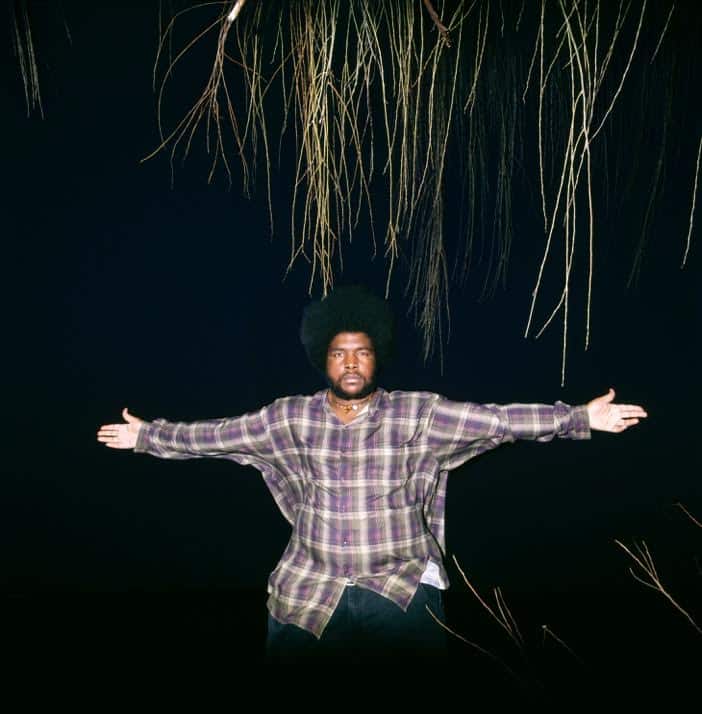

I just got really excited about things that I’d forgotten about. For instance, I’d shot The Roots maybe twenty years ago and one of the guys didn’t show up. I’m thinking, “Really? What’s a group picture without the full group?” I never really went back to the session because I always figured, what’s the point. But when I was sorting through my archives I found a solo picture of Questlove and I thought, “Oh this is cool!’ And I didn’t even remember taking it.”

Questlove – Photographed by Chris Buck

In the book, there are maybe 72 pictures that I’ve not shown before. And that’s pretty awesome! It’s around a quarter of the book.

Were there things you realized about your own work that you weren’t aware of before?

You mean pictures or actual whole sessions?

In terms of You, more than anything else.

Oh, like, you mean stylistically?

Yeah!

I think it was more consistent than I would have thought. Not in terms of quality level, but as a stylistic thing. Because now I have the perspective of time. I can look back and see a sense of who I am as a photographer and what I’m drawn to. And to find pictures from the early 90’s to have something like that is really fun. But one thing is that, for some shoots, I’ve pulled different frames than I picked out back in the day, but for the most part, my editing approach is the same. There’s the gift of time. You know, when you come off a shoot, you’re generally headed towards pictures as close to what you were aiming for. Which isn’t really the ideal way to edit.

Hahaha!

Because there are definitely better pictures that just weren’t what you were going for. And you try to do that in real time with your work, but it’s hard to because I aim for this or that and it equalled what I thought it would be. You’d like to think you have a vision. You don’t like to think that random shot on the third roll, something that just happened is the best one…

Yeah exactly. That it’s better than what you had planned.

Yeah, that’s not good news, but it’s often true! And you choose the best shot and if you shot it, it’s still yours.

Hahaha! What were you most surprised by, going through it all?

I was surprised by was how many tight shots I had. In the 90’s and Aughts I tended to…Something about the body just spoke more to me, so I was always just backing up and backing up to get the full expression of the body. But as I was editing for this book I was picking out a lot of pictures that are tight, and part of that has to do with I’m doing the book Now and I’m interested in tighter portraits, now.

1. Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer of Broad City – Photographed by Chris Buck

2. Lena Dunham – Photographed by Chris Buck

Ah, okay.

I think that’s partially because of the camera I’m shooting with. But also there is something very powerful about a strong face portrait. And having them, I don’t know, they used to seem kind of easy, and in a way they are easy. I mean, it’s funny, I kind of have this theory on portraits that I came up with recently and it’s that portraits are the thing that we connect to easiest. As human beings, we like to look at other human beings.

Right!

Portraits are quite powerful and we really love them but they’re also…well…whatever, obviously I’m super-biased because it’s what I do. But I think it’s one of the harder things to do in photography because you have to get…there’s a psychological aspect too, because you have this person in front of you, and the human instinct is to be social and the social thing in that moment is to do something that’s going to please that person, because you’re a nice person and why would you not? But the best pictures often come from ignoring what that person would want.

It’s funny because we interviewed Art Streiber recently and as we’re talking, he’s answering questions and he’s laying out approach to photos that’s almost the opposite of what you’re talking about. He was really interested in making his subjects comfortable, and he wants to work with them as sort of a collaboration in a celebratory way, he wants to show the best portrait that they also want to show.

Sure. I think that’s a legitimate approach. He’s a great photographer; I have a lot of respect for him. But I also recognize that different people have different ways of getting to where they need to be.

I actually brought it up to him. I said, “You know I talked to Chris Buck, and he’s got this very different way.” And he was also very fascinated by the fact that there’s these two different/opposing approaches to get great portraits.

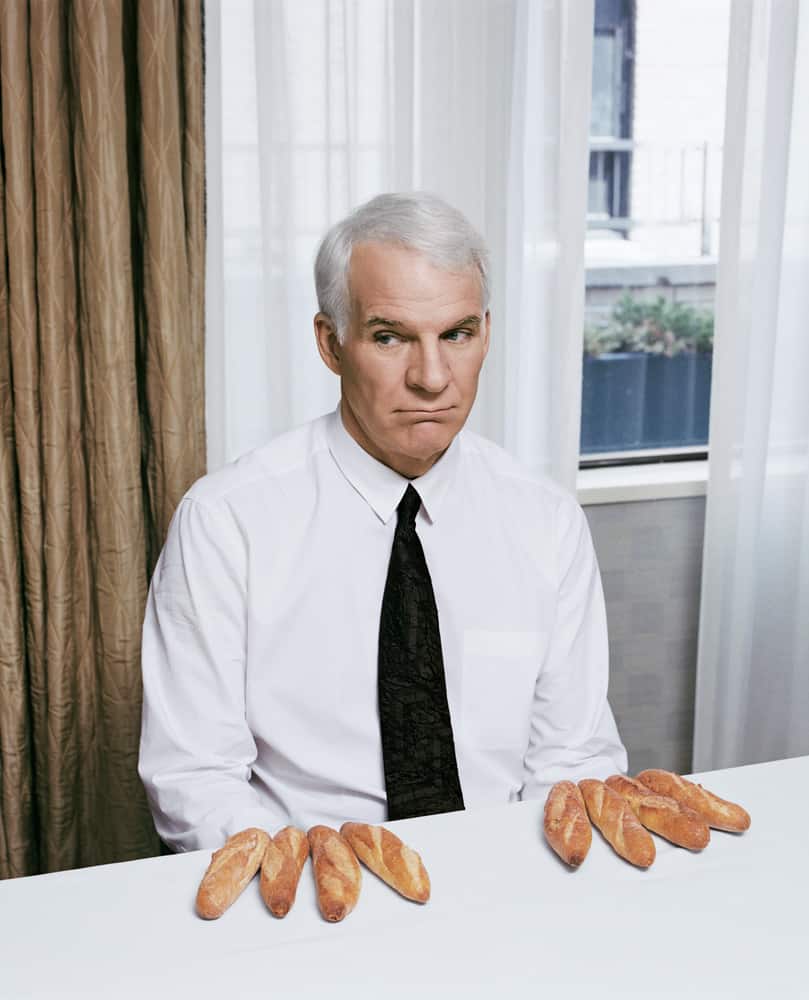

I think I have a reputation for making people uncomfortable, and wanting to, and I think that’s overstated. I think there’s an aspect of having some level of control of the vibe on the set that I do exert, but I don’t think I’m cold on set or rude or anything, I don’t do overt things to prod people. It’s a benign dictatorship. Hahahaha.

1. Steve Martin - Photographed by Chris Buck

2. Martin Short – Photographed by Chris Buck

Haha!

But it is a dictatorship, and obviously that’s a kind of negotiated position, and I recognize that there’s multiple power players in the room. There’s my client, there’s the publicist, there’s the subject of course, often there’s the subject’s makeup artist. And there’s other legitimate creative people in the room…there’s the prop stylist or the wardrobe stylist who genuinely should have a chance to weigh in. I mean, of course my client, more than anything my client.

Hahaha, “and then there are some other legitimately creative people in the room.” Why did you feel the need to make this book now?

Well, I tried to make it ten years ago and had little-to-no interest from publishers. I made a mock-up, we tried different approaches. It was really…it was chilling.

One of the things I was told at that time was, “You know your body of work is interesting, but it’s covering such a wide range of people and vocations that we can’t sell this to the punk rock crowd, we can’t sell it to the political crowd – there’s no one thing that links it together.

Well there is, it’s you, but no one knows or cares who you are.”

Ha!

And I was like, “Ok I’m going to think about that and keep that in mind, and also, Fuck You.”

What the book is now is largely formed by that experience. The fact that it’s a thirty-year retrospective, 1986-2016, is to frame it as a cultural overview. And to give it a single thing that links it together.

It also adds another ten years of my career, and thirty years becomes history in a way that twenty years is less so. Ronald Reagan was president when I shot the first picture, this is a long time. So it really becomes a cultural record on top of being my story as a photographer and as an artist.

The “Fuck You” aspect is that in making the book, I no longer was open to or interested in doing the “Greatest Hits.” I wanted to do a book that was very personal and that’s why a lot of the really niche people are in there, they’re pictures that I like, or people who I think are cool. It’s not just my viewpoint as a photographer but also my edit as a person, as someone interested in culture and the world.

Something else also happened! I was called to photograph a second-tier Congress member who was running for president. And that picture ended up becoming a political and media firestorm, and that, weirdly enough, led to me getting a bunch of cover shoots.

Michelle Bachmann – Photographed by Chris Buck for Newsweek

You think that was it, huh?

I really believe that it became…I mean obviously that picture in its technical aspect is very straightforward and simple. And it was totally a Chris Buck edit, I mean, that’s a total Chris Buck picture.

It’s very much a Chris Buck picture.

This picture became one of the most notable covers of the year, and became part of the pantheon of important magazine covers, historically. So I became someone who “was good at doing covers,” apparently. And the fact is the person on the cover is probably the most famous person in that issue, right?

Right.

That’s why they’re on the cover. So, suddenly I went from shooting one A-lister a year to every third shoot was an A-lister.

In fact, when I had to photograph the president, it was the same client that I had when I had to shoot Michelle Bachman, so that was the best shoot of my career and it was hired by the same person. Obviously he felt the Bachman shoot was successful. And he even said, when he hired me, “If you could get some kind of Chris Buck shot with him, it’d be amazing!”

I remember thinking that if I ever got to shoot A-list people regularly, and to shoot them the Chris Buck style, that was the goal I’d not got yet. Because when you get to shoot these people, oftentimes, the pictures are fine, but not as strong.

One of the great successes in shooting President Obama was that I got a Chris Buck shot out of him. It was amazing, in four and a half minutes, you know. And it’s not like the quirkiest picture in the book, but when you look at it, you’re thinking, “There’s some Chris Buck in there.”

Once you photograph a sitting president, who is like a matinee idol, too, you can do anything. After photographing the president, I could photograph anyone, and I could be totally fine.

Did you walk away from the shoot with that kind of feeling?

I was walking on air for months. It really was the most important shoot of my career. It really felt like that was a major benchmark.

1. Bryan Cranston & Jon Hamm – Photographed by Chris Buck

2. Billy Bob Thornton – Photographed by Chris Buck

Right, but this sort of harkens back to our last interview, do you still feel challenged, creatively?

I’ve thought about that interview since, and the fact is that I don’t know how you can keep making work if you don’t believe you can do better than you’ve done before. Not just do more, but, like, you’ve not gotten it right yet. You have to really feel like you’ve not got it right. I know that sounds crazy on some level, but I feel like I can make better pictures than I have.

Yeah, is there a tangible kind of creative goal?

Uh yes! Immortality!

Hahahahha! Because I remember in our last interview, you realized at a certain point you would never be Irving Penn. But is there a part of you that kind of thinks that maybe you can be?

Doing this for thirty years, I guess that one of the conclusions I came to would be, putting aside the question of his level of excellence, I feel like I have achieved something of that goal. I met Tom Wolfe when I was in my mid-twenties, and he came and spoke at a thing in Toronto. And I met him afterwards, at a little meet ad greet. And I said, “I knew who you were because Irving Penn’s photographed you.” And he laughed because obviously it sounds ridiculous. But I loved Irving Penn’s work, and if he photographed you and made you look cool, then you must be someone worth knowing. And I hope that I’ve done that with this book.

One more question: Did you have any concerns regarding crowdfunding?

…your questions are too good.

Heheh, I’m trying to be the best what can I say; I want to be the Irving Penn of interviews.

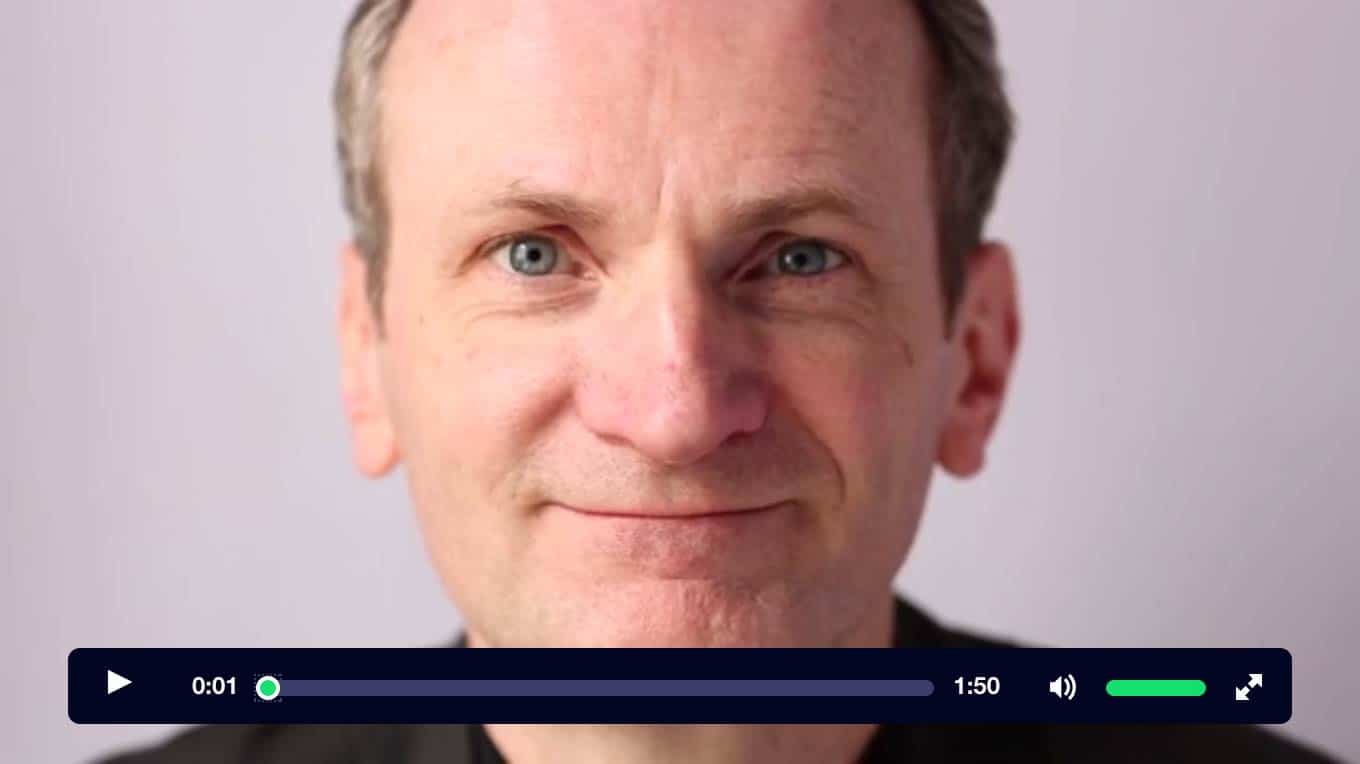

Ha, right, you want to be the Tom Wolfe of interviews. I had a real hard time making the video in particular.

A Still from Chris Buck's Kickstarter for ‘Uneasy’

I was really impressed with the video.

Thank you. Kickstarter is a popularity contest where you vote with your wallet. The fact is that when you go to do it, you’re basically saying, “Please like me, and express it with your money.” Now I ran for student council in high school, and I lost. I even ran for the most pathetic position (the Publicity Director). And so losing a popularity contest teaches you “don’t run for a popularity contest!” And in a way, it probably colors the way I photograph, “I don’t care if you (the subject) likes the picture” vibe. And I don’t even care if the audience likes the picture either. I make the work I like, and I build a career on not caring if you like it. And I think doing a Kickstarter is totally the antithesis of that.

I brought in two of my smartest former interns and had them help me with it, and hold my hand through the whole process. And we shot three days worth of video. And basically tried to do it like four different ways. And then combined the material with a great editor (Eugen Sakhnenko).

Yeah, because it’s really good. Who did the voiceover?

My intern Alexandra Genova, her dad owns a car dealership, swear to God, in Rochester, New York, and he hires people to do radio ads, and this woman who does the radio ad did our voiceover.

Were you concerned that you wouldn’t reach your goal?

Of course. One of the things that put me at ease was, we watched a bunch of Kickstarters, and my current intern too (Alexey Korotkov), he really understood Kickstarter and helped me to understand what it was. He showed me some very good ones, including Alec Soth’s recent one, his was great.

I didn’t want to be overtly asking for money. I wanted to frame it like, “We’re doing a fun, exciting project; we’d love you to be a part of it, and I think you’ll be glad you are.” And also the voiceover thing allowed her to say how awesome I am without me having to say it. Alec’s was a minute and fifty-nine seconds, and I thought, “Absolute genius!” Because it’s not two minutes, and I will watch it.

The first thing everyone thinks when they see there’s a video is, “How long am I committing to, here?” And I saw some were four and a half minutes without good sound. Who watches that?!

No one? (interviewer thinks back to his Kickstarter, his video, around three minutes, thinks wistfully of what might have been, had the video been shorter.)

The one that had four and a half minutes without decent sound reached, and went beyond their goal. So I tried to set a goal that I thought was somewhat conservative. It’s actually half what the book costs. I was going to do the book either way, but this allowed to me garner interest, and get preorders, and frankly to also have cash flow. I’m not going to get money for selling the actual books until the end of the year, I need to eat in the meantime. The Kickstarter allows me to eat and pay my mortgage!

I think that’s a fitting end. Thank you!

I really appreciate it!

⁂

All images from ‘Uneasy’ courtesy Chris Buck. Please support the Kickstarter Campaign, a book of Chris Buck’s portraits of the famous with 338 color and black-and-white photographs, from 1986 to 2016.

1. Nick Offerman – Photographed by Chris Buck

2. Jay-Z – Photographed by Chris Buck