Interview 053 • Sep 1st 2016

- Interview and Portraits of Tabitha Soren by Lou Noble

About Tabitha Soren

Tabitha Soren left a successful career in television in 1999 to start another one as a photographer. Her work is included in public collections such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Oakland Museum of California; Transformer Station, Cleveland, Ohio; Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco; New Orleans Museum of Art; Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, Indiana; and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, New Orleans. Her work has been featured in Dear Dave, McSweeney’s, Vanity Fair, New York Times Magazine, Blink, Slate, New York, Sports Illustrated, California Sunday Magazine, and ESPN The Magazine. She is represented by the Kopeikin Gallery, Los Angeles and her first photobook, Fantasy Life, will be published by Aperture in the spring.

Links

Foreword

So many of us worry, anxiety-ridden, about finding a theme or purpose for why we're shooting. What am I trying to say? What is my artistic intent...

But Tabitha Soren poses a different approach. Shoot what intrigues you and look for patterns later. Shelve the anxiety, and be open to the patterns that organically emerge. It's a deceptively simple lesson in letting go and allowing the work guide you...this is the kind of interview I savor.

- Agustin

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

Let’s start with a softball question! Do the themes for your work come first, or do you shoot and then find the thematics afterwards?

Most of the time, I take a picture and I fall in love with it, and then I try to take more just like it. And then I wait for the theme, which is actually very important to me, to sort of pull itself to the surface. I start with something really rough, it generally is something that I’m just making up, so I can take more pictures like the good ones. So I feel like the first picture is a gift, it’s not something that I necessarily went after. I have to say that, in the last couple years, I’ve had more ideas than time, and that feels really good, because that hasn’t always been the case. But the exceptions to this process are the Fantasy Life work, and a series I’ve been working on since Katrina in New Orleans, so there are some that are rooted in an idea to begin with.

Right.

Both of those are…I have ten places in New Orleans that are either rebuilt or abandoned, and I take their picture almost every year. And then Fantasy Life definitely started out as a way to chronicle the arc of someone’s, presumably, very successful career. I knew some of them would be successful, but I wanted to follow how they changed physically. I had Rineke Dijkstra’s pictures of Israeli soldiers, and the young girls, and the pregnant women, in my head. But that project didn’t end up developing in that way, because my athletes kind of stayed very in shape, they stayed very healthy, they were young to begin with, so there wasn’t a lot of radical change that I witnessed in front of the camera.

Right.

There were a couple people who looked like maybe they did steroids on and off, and that change was noticeable, but it wasn’t enough to sustain a whole project, so I had to come up with some other idea.

And for your something like the Katrina project, do you know what it is you are trying to capture at the time, or is that something you want to see once you’ve shot for a length of time?

That’s a good question, because that was given to me on assignment for The New York Times magazine…I’m very interested in how people behave in a moment of crisis, or a moment of panic, I feel like life is always throwing everyone curve balls, and it’s just, the only way to find happiness is to figure out a way to deal with the bumps or avoid the bumps. I mean, obviously Katrina is more than a bump.

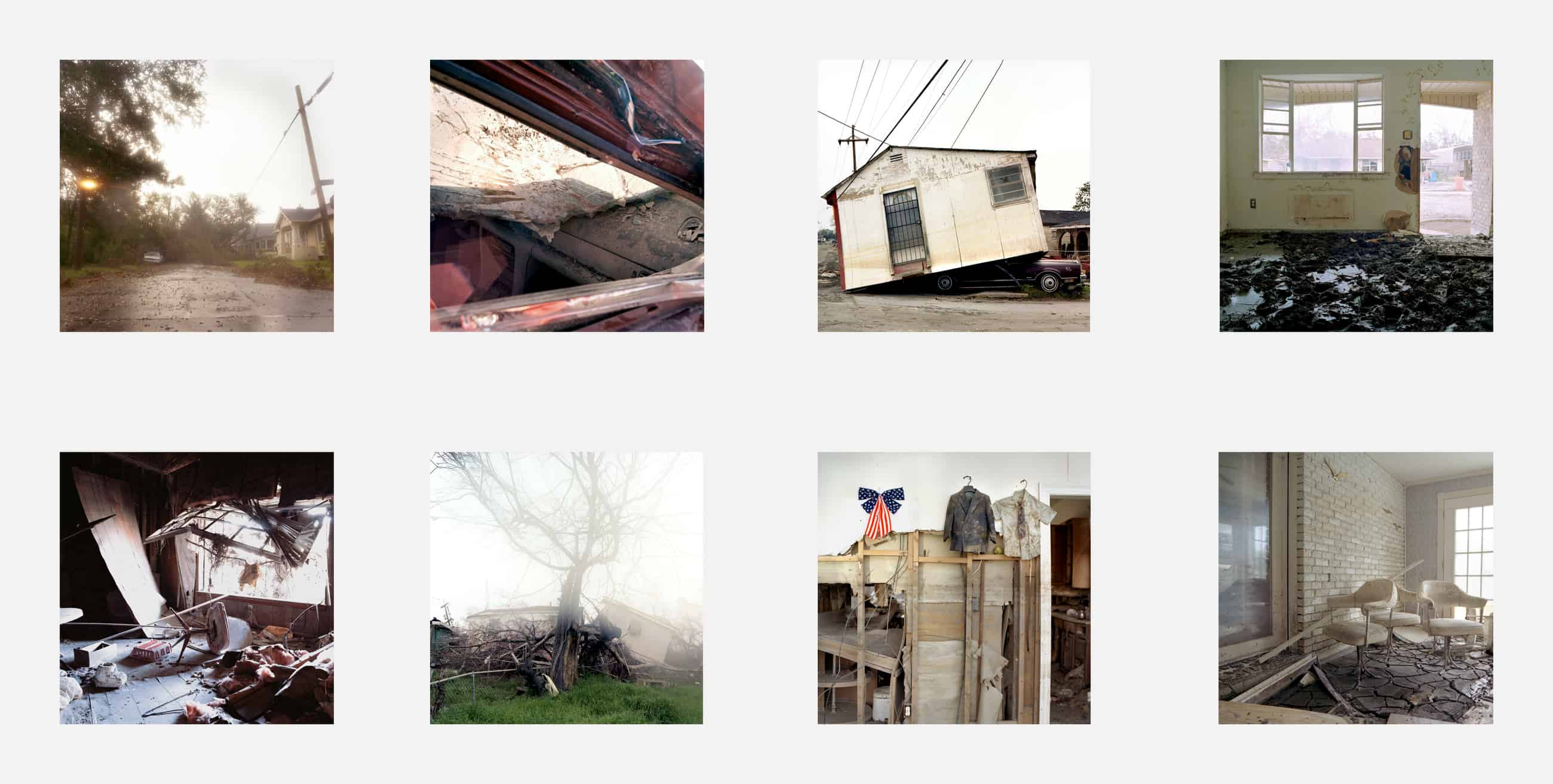

Selection from Uprooted - Tabitha Soren

It’s crisis, definitely.

I’m interested in what those people do with their homes. I’m using the residents of the building as metaphors for home and how in a radically-changing place, like New Orleans specifically, how they sort of inhabit these spaces and make them homes despite what happened ten years ago. Or some of them, some places have new residents living in them, and they’re still right across from the canal. The psychology of “home” interests me a lot, probably because I grew up in a military family and moved around all the time, so the idea of living in one house for a long time, or one city for a long time is very foreign to me.

Hmm, yeah.

So the Katrina thing is a little bit of its own special case because it started off as an assignment from Kathy Ryan (The New York Times Photo Editor).

Right. Why is it you think you’re attracted to crisis? Artistically?

Oh I wish I knew, it’d be so much easier, hahahaha!

Hahaha!

I think that, I don’t know, I’ve always had sort of an edge to me, I’ve never felt completely…it has to do with my own anxiety and the challenge of navigating the twists and turns of every day life that I just feel like it’s a bit of a struggle for me.

Yeah.

And I have always felt a little bit…I guess something being in the military and being in a new place all the time, I was always an outsider, and that feeling just didn’t go away as I got older, and then I got into television and I felt a little bit like an outsider when I worked at NBC and CNN and ABC, very mainstream, conventional places where I felt like I had to kind of hide parts of my personality because they just weren’t mainstream enough. So that reinforced not fitting in.

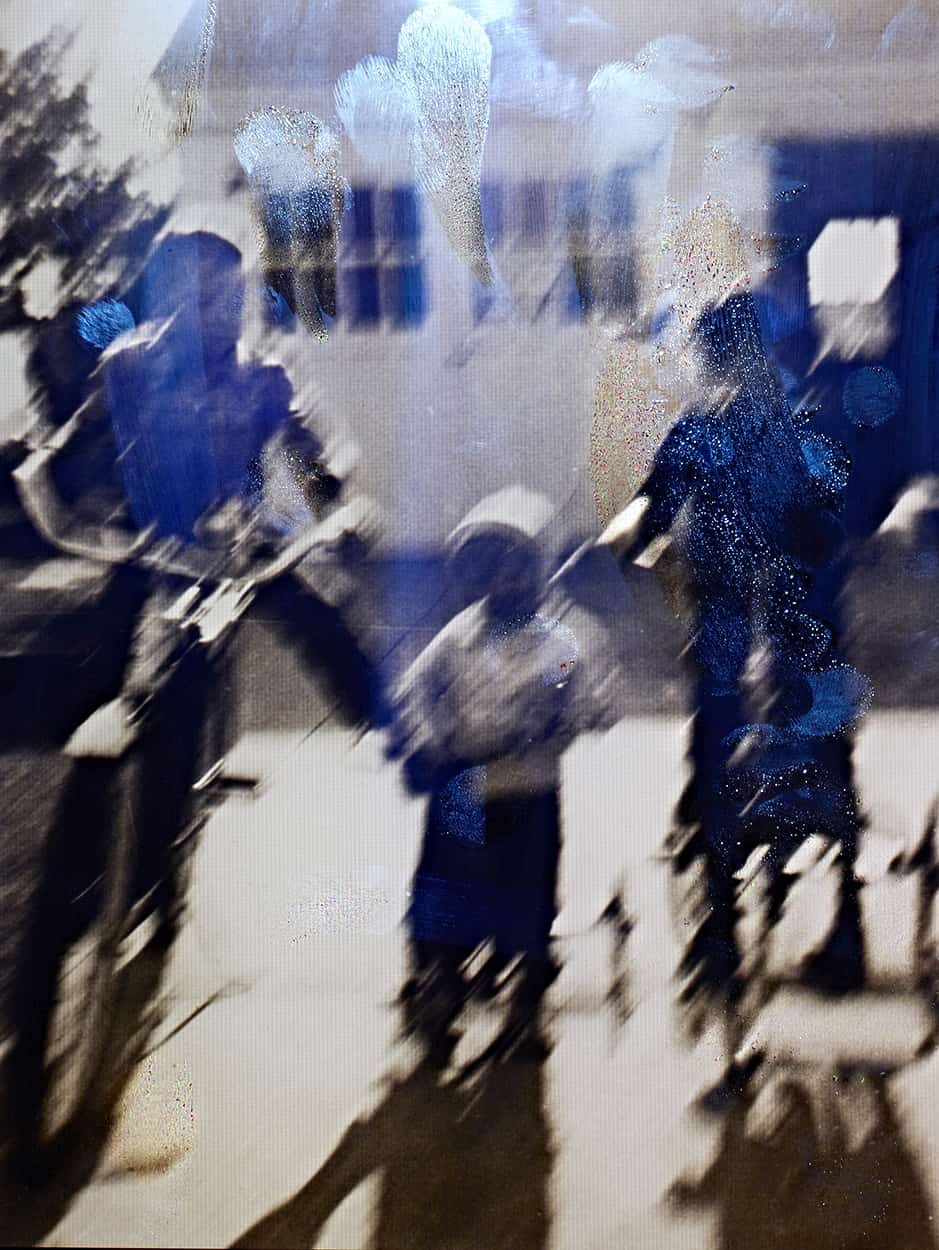

It just amazes me what people survive and what people don’t. And so the different areas of one’s psychology interests me a lot. The Running work was about fight-or-flight response.

Right.

That was a very specific thing. The Panic Beach series of oceanscapes started after I had my first panic attack after delivering my third child, sometimes hormones do that, but I wasn’t prepared for it at all.

Sure.

And then I’m working on something now that hasn’t kind of come to total fruition yet, but it’s…

The arrows and BB gun?

Yeah, it’s describing some sort of unease…

From Untitled Series – Tabitha Soren

Does photography feel cathartic for you, then?

Yeah, it feels super-personal. I feel like I’m finding, I mean, when I was a journalist, I was after a particular kind of truth, and the truth that I’m pursuing in my artwork is a much more emotional, psychological truth.

Mhmm.

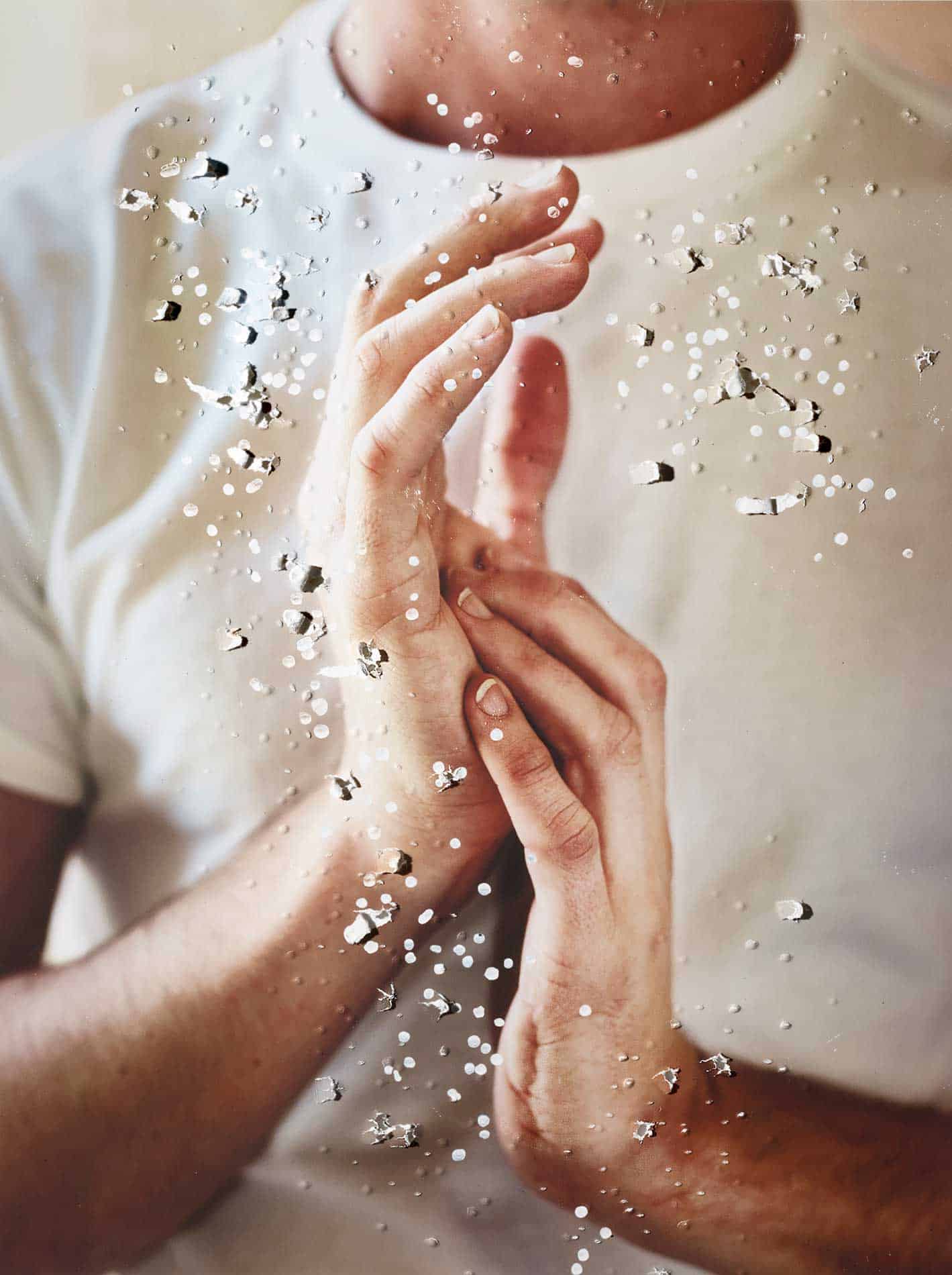

I think that this, my Surface Tension work, the fingerprints on the iPad, that’s definitely about technology and trying to adapt, but it’s also about the anxiety that occurs when we’re trying to keep track of things that are either unknowable or unseeable or fleeting. I feel like there’s a lot of struggle of forces that we feel in our heads with all these devices we have and all the different ways to communicate now that didn’t exist before. So, even though I go and I start this project that doesn’t look like the last project, at the end of the couple of years of work, it really does end up coming back down to a psychological portrait, in some way.

Right.

I’m trying to visualize psychological states, or the internal weather that storms through each of us and yet my projects don’t look anything alike! Someone told me early on that that was career suicide…but they kind of come out the way they come out.

Hahaha!

I wish I was more like Todd Hido, or…I don’t know. But maybe I will just have a longevity, because certainly there are examples, like Catherine Opie, her work never looks alike. Richard Misrach, same thing. So I do have some people who work in the same way that I do.

And I also think, what I really enjoy about your work is that, I mean, there are several things, but one that comes to mind is that, while it’s clear that it is talking about psychological states, it’s not overbearing. It’s not working too hard to sell the theme, if that makes sense?

That’s probably because the theme doesn’t come to me until much later.

Right. But it also seems like that’s a through line, while your work may look different, it all has the same feel, where I can tell the work because of how psychology plays into it, what it’s trying to convey.

I’m definitely attracted to mistakes and accident, and not only how people react to that, but how I’m using those forces in my work. Things that are imperfect are more attractive to me than the opposite, so the beauty, I mean this happened when I was working on documentaries as well, but getting that unexpected, amazing picture that you didn’t set out to take, but…that’s so exciting.

Ha!

And then you don’t really know where it came from. That doesn’t mean that there’s some muse or something like that, I don’t think that art is magic, I think that you have to open yourself up and work really hard, and that’s when those images show up in your viewfinder.

From Panic Beach – Tabitha Soren

Right! What was it that initially attracted you to photography? Were you looking for something to move into, or were you still thinking of yourself as a journalist when photography grabbed you?

I got a little burnt out after covering the ’96 presidential campaign, and I met and fell in love with my husband…I was really was resisting the pace of being on planes all the time, and flying to Bosnia and interviewing Yasser Arafat the next day…

Hahaha!

Every time I woke up there was this huge, high-pressure oval office interview to prepare for, and I just felt rung out. So I took a Knight fellowship at Stanford, where they pay your salary to go to school for a year. I was supposed to be getting deep into one particular area, because of course the curse of journalism is that you just skim along the top, because of the pace of it, in terms of your knowledge of a particular subject, but I ended up studying with Alex Nemerov in the Art History department, and falling in love with taking pictures. Photographers like Joel Levick and Bob Dawson and Lukas Felzmann were so welcoming and so encouraging. Again, I was the outsider, I was, like, a 30 year-old student who was always raising her hand and sitting in the front row and wanting more homework, having fifty pictures, instead of ten, for their critique.

Hahahaha!

Totally obnoxious, like, “Really excited to be there” old person. I would just lose track of time in the darkroom, and they finally just gave me a key because I was always too early and staying there too late. I think that I needed a way to not feel like I was rushing through life, and I feel like art is another place to observe your interior life, and it slows you down. So…art is the antidote to Americans being in too big of a rush to bother paying attention to how they’re feeling, what they’re thinking, and often even what they’re doing. I mean, Surface Tension is a lot about that, because how often do you have two hours on your computer and you have no idea what you’ve just done, or you end up on some weird website, like, “Shit, I didn’t have time for that! What just happened?”

Right!

You go into some k-hole. So having those fingerprints and those traces pile up on an image, it’s almost like a map of how I’ve spent my time, or how my son has or whatever. And the background image is, just as an aside, it’s always some picture that I had looked at through that session of internet-searching or email-looking or social media.

In those early days, was it also an exploration of psychology, of internal states?

No, it was learning how to use the technology, learning how to use a view camera, how to lug it around. All the basics: black and white, what’s the difference with color…I was a very excited student, but I was ignorant.

Sure.

I had certainly taken pictures as a child growing up, but none of it was art. I did chronicle a lot of stuff, though, because I had a new bedroom every couple years, had a new desk, what did my friend look like, what did the school look like, what was my bike like, what car did we have, the front of the house, the neighborhood. All of that stuff was changing and I just couldn’t remember what it was. I don’t think I was conscious about why I was doing it, my poor parents have these scrapbooks full of pictures of my blue shag rug, you know, just weird, hahaha!

Hahaha!

They could be sort of post-modern in their banality. My desk with a chair in front of it and a pink plaid cushion. But those sorts of bits and pieces, I do think, make up a life, ultimately, on some level, and I guess I didn’t want to be deprived of it.

Do you still have those photos?

I do have some of them. When I do an artist talk, I pull some of them in.

Ahhh nice.

Just to level the playing field, I want people to know that, through mastery, we can all start again, and I didn’t have any particular talent from the get go.

Right.

I certainly think that journalism and working in television for all those years informed how I compose a picture, because I did produce and direct most of my own stuff until I was being pulled in forty different directions and just didn’t have time to, but my first job in Vermont was what they called then “a one man band”, where I was shooting my own work, so I got to make every mistake in the book, not white balancing, so I’m blue, and I would cut off my forehead. Through a governor’s press conference, I had the mic in the right place, and the light, and everything was great, and I look down at my machine at the end, and the audio cable wasn’t all the way plugged in.

From Surface Tension – Tabitha Soren

Hahahaha!

So, you don’t make those mistakes a second time. And that’s why you start in a tiny market like Vermont. That’s also where I had pretty “brilliant” hair.

Ha!

It was like a twenty-two year-old pretending to be thirty-two, I had shoulder pads and giant helmet head.

That’s the late twentieth century, for ya.

When I went to MTV, I had such short hair because they cut it all off, I just remember this guy in New York just speechless because of my hair, “What am I going to do with this?? You know what, we’re just getting rid of it!” And all of a sudden I had this tiny little bob.

Hahahaha!

It was the worst, I hated it so much, hahahahaha! Anyway…

You mentioned you were looking for a different kind of truth as a journalist than you were as a photographer. What kind of truth were you after?

Well, for politics, you’re looking for “who what when where and why,” because that’s the best way to get to the heart of why people are caring about this particular subject. But for photography, it’s much more subtle, it’s about the sublime, it’s about a feeling that…it’s another place to observe your interior life. I think, for me, the act of photographing bears some resemblance to how we consciously manage the uncontrollable things, the uncontrollable set of possibilities that exist in life, and that’s the truth of life, that you can’t control it.

Amen!

So for me, photographing allows me to manage it a little bit, by exploring it slowly and deeply without taking pictures of people demonstrating these different psychological states, that would be corny.

Heheh…were there certain photographers that you really looked to, at the time? In the beginning?

Oh yes, you know, Rineke Dijkstra, definitely her, definitely Nan Goldin, certainly Eggleston. I had studied Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, so Walker Evans was in there, although he seemed very strict, and it took me a while to really appreciate the brilliance there. Robert Adams, Summer Nights, Walking just floors me, still. Who else…I’d say that’s…at Stanford those were the people I was thinking about.

Right.

And Richard Misrach, and I think pretty soon, taking it into a more professional realm, I discovered Katy Grannan, I’m a big fan of her work. I keep waiting to take pictures like some of those photographers I like.

Ha!

Hahaha! I like a lot of photographers whose work is really sort of…it looks like they’re shooting from the hip, it’s just natural, kind of punk rock, seems effortless.

Like Winogrand…

Yeah, it’s never like that. Mine is “cinematic,” and…I don’t know how people would describe my work, my work is really really heavily thought out. And those running shoots were a pain in the butt to set up, the lighting, it was just very tricky and complicated.

From Fantasy Life – Tabitha Soren

On your website, there’s one quote that really spoke to me: “There is a central American fantasy that says that we have to do something extraordinary to lead a meaningful life.” Is there that element of The Pressure of Society in your work?

Well…I mean, I don’t think about that, but I would say my friends, my photographer friends, who counsel me when I get down, say that I am unnecessarily hard on myself because the art audience is so much smaller than the audience that I had in my previous job.

Sure.

And that it set some sort of bar…

That’s not good.

But it doesn’t stop me from doing it, it’s certainly not something that’s conscious, but I’ve never been very good at doing something at like 80%, I’ve always been one of those people who did 110% even though it’s completely unnecessary. So I think that has a certain amount of pressure, aiming for success. I know that as a human being, I would not be content with making art and having no one see it. And I know there are very happy artists who work that way, and I am not one of those.

Right.

It is definitely a form of expression for me, so if I’m expressing something, I want actual people to be on the other end of it.

Yeah, totally. Is there that pressure to…in that statement, do you feel the pressure to lead a meaningful life?

Absolutely! I live in the capital of deep meaning, Berkeley, California.

Ha!

You can’t get away with skimming along the surface, here. I definitely feel like there is pressure to, not only have a meaningful…I mean, everybody wants a meaningful life, I think it’s Americans’ definition of “meaningful” that could be adjusted a bit, that we don’t have to be number one.

Ahh.

There are all kinds of different definitions of happiness, and I feel like actually the West coast has a much more varied approach to that question.

From Surface Tension – Tabitha Soren

Totally.

When I was in New York, I felt like it was definitely about money and getting to the top of the ladder, whatever that is. But what I found was, the higher I got, the more conservative and conventional the work space became. I didn’t want to make the sacrifices I needed to in order to succeed on that level. It seemed false, and I always felt like I would be imitating a journalist, at a certain level. So the art world feels much more true, to me, and as arbitrary as the whole thing is, the money side of it, the actual process of making work feels authentic to me. It feels like where I’m supposed to be. I don’t feel like I’m faking any part of it, maybe at an art fair every once in a while I’m faking enjoying small talk…

Hahaha!

But most of it feels really emotionally true, and I think, for me, that’s an important quality of a meaningful life. I wish I didn’t care about people seeing the work or being successful, or having galleries sell it…I think I would be much happier if I didn’t think about that stuff at all.

Sure.

But I would be lying to you if I said none of that stuff matters.

Thank you for the truth.

Hahaha!

Has your art career given you a different perspective on your journalism career?

Hmm, I’ve never gone backwards like that, I’ve only thought about the effect of journalism on art.

That’s easy!

You know, only that it seems much more personal, it’s much more emotional, it’s about me. These pictures, in the end, I feel like they’re very much a self portrait. I was working with a curator in Houston who was looking at the Surface Tension work, and she kept trying to force me to explain why I picked the images that are behind the pictures, and I was having a hard time coming up with a net that pulled them all together, besides the theories that you and I have talked about, and I’m like, “ahhh, umm,” and she said, “they’re a self portrait, that’s the answer!”

Ha!

I’m like, “What??” That’s a nightmare, I could never take self portraits, I would never want to do that, but that’s what they are, this is how I’m spending my time. I’m trying to find a route to a softball tournament to take my daughter to, and there’s fire in the area, so I don’t want to get stuck in that traffic, I go on GPS and there’s a video news report on the fire, and “oh, that would make a good picture if I freeze that,” so it looks like an apocalyptic thing, but mainly it was just a mapping tool. So I really like the way art raises the Mundane of life into something really special.

It elevates it.

Yeah, yeah, because that was just a GPS thing.

From Surface Tension – Tabitha Soren

Right! It sounds like this is a much more satisfying career for you.

Well, it certainly is, at this stage in my life, yes. I mean, my twenties were great, I expected to be a reporter, I was always a writer, and I knew that I wanted to study journalism and politics in New York when I was eighteen, and I worked at CNN very early. There was definite ambition and direction there, and I did it for thirteen…I don’t know, I had my 18th birthday at CNN…

Oh wow.

And I probably got to Stanford when I was thirty, so, you know, I worked really hard and enjoyed that for a while, it’s just when…I think the most interesting people are the ones that change their mind, or have second acts, or wanted to explore something new, and I don’t think I’m that unusual to have more than one career.

No, no.

It’s hard, I think Americans have a hard time repositioning a person who was in the public eye into another role.

Sure.

So I don’t know how much that affects my career or not, but thankfully I have a gallerist who says, “Look, Tabitha, you weren’t that famous!”

Hahahaha!

Hahahaha! So, alright, great, we’re just going to keep making work and go forward and not deal with all that. And I did make a concerted effort to just be in every group show in the Bay area, and non-profit galleries, and bars, just get my work out in every small nook and cranny that I possibly could and not trade on…

Your name?

Yeah, that’s even amplifying it, but I just kept them very separate, I just started from the bottom, and I’ve been doing this now for as long as I did journalism, nobody paid attention until fairly recently.

Really?

Yeah, I mean I, my first running picture, my daughter, I think she’s seven in that picture and she’s seventeen now. I woke her up at dawn, pulled her out of her bed, had her put her nightgown on backwards because it had Cinderella on the front and I didn’t want the text, and I ended up shooting her from the back, hahaha!

From Running – Tabitha Soren

Heheheh.

See, there you go, best laid plans! Put headlights on her in the car, got the rental car in the driveway, so that was the first picture I took that looked like running, and I showed it to a very fancy photographer, and he said, “Just take more of these!” I was like, “I don’t have a project, I don’t know what I’m going to do”

“Just take a lot of this picture.”

“What, people running over and over?”

“Yup!”

“What should we call it?”

“Running?”

Hahahahaha!

Hahahaha! And it took like three years for me to figure out it was about fight-or-flight. I knew it wasn’t about athleticism. Sometimes you just gotta marinate in it.

Especially online, series have gained in prominence, people are much more receptive to photo-series than they were in the past, from my perspective.

Yeah, they have the patience for it, you think?

I don’t know, I think people, and this is kind of just spit-balling, I feel like it’s easier for people to understand when there’s a bunch of photos all together.

Yeah, well, you know what that may be from, that might be the result of, and I’m spit-balling, too, but because everyone has such a fantastic phone camera, and because of social media, they are taking all these sort of one-hit wonders, it’s like a great picture here and there and there and there, so the professional, the artists separate themselves by diving deep.

From Running – Tabitha Soren

Yeah…yeah.

The equipment now is very, it’s much more inclusive; anybody with a nice digital camera…it used to be the technology separated people.

Right.

You know, the amateurs from the professionals, but now that’s not the case. But now, it’s just about having something to say.

Yeah.

And I don’t have a problem thinking like that, anymore. That hasn’t always been the case, hahaha. I feel so grateful, I wish I had more time, but that’s the best thing about art: I don’t have to stay wrinkle-free, young, to do it…they can wheel me in to a solo show in a wheelchair. I try to take a long view.

Sure.

I don’t get to work as much as I want to. Certainly, when you’re consumed with a project, you want to stay and keep working. I have a billion interruptions from my three children, and just regular life, and that can get me very frustrated and irritated. What stops me from flipping out about it is taking a long view.

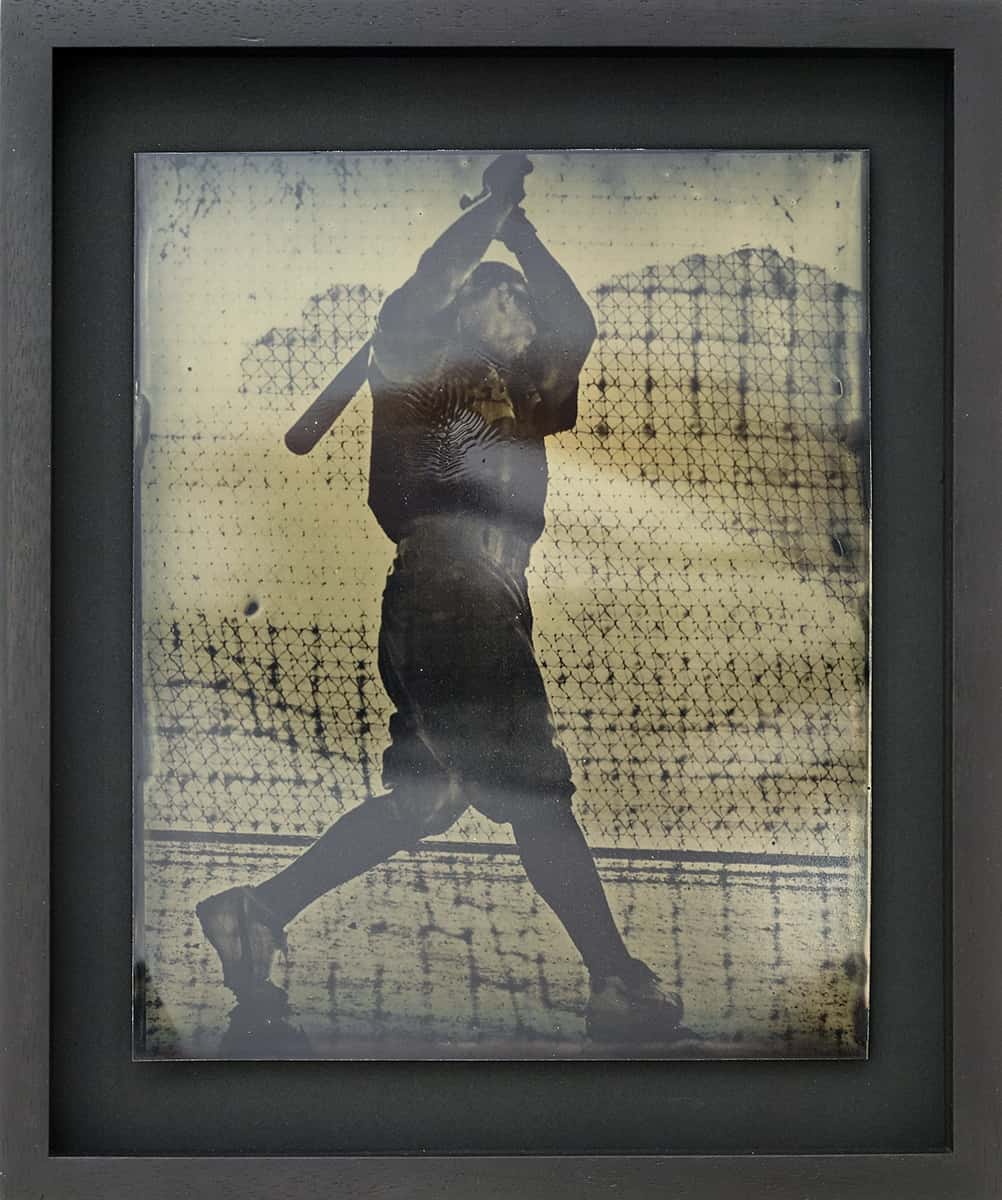

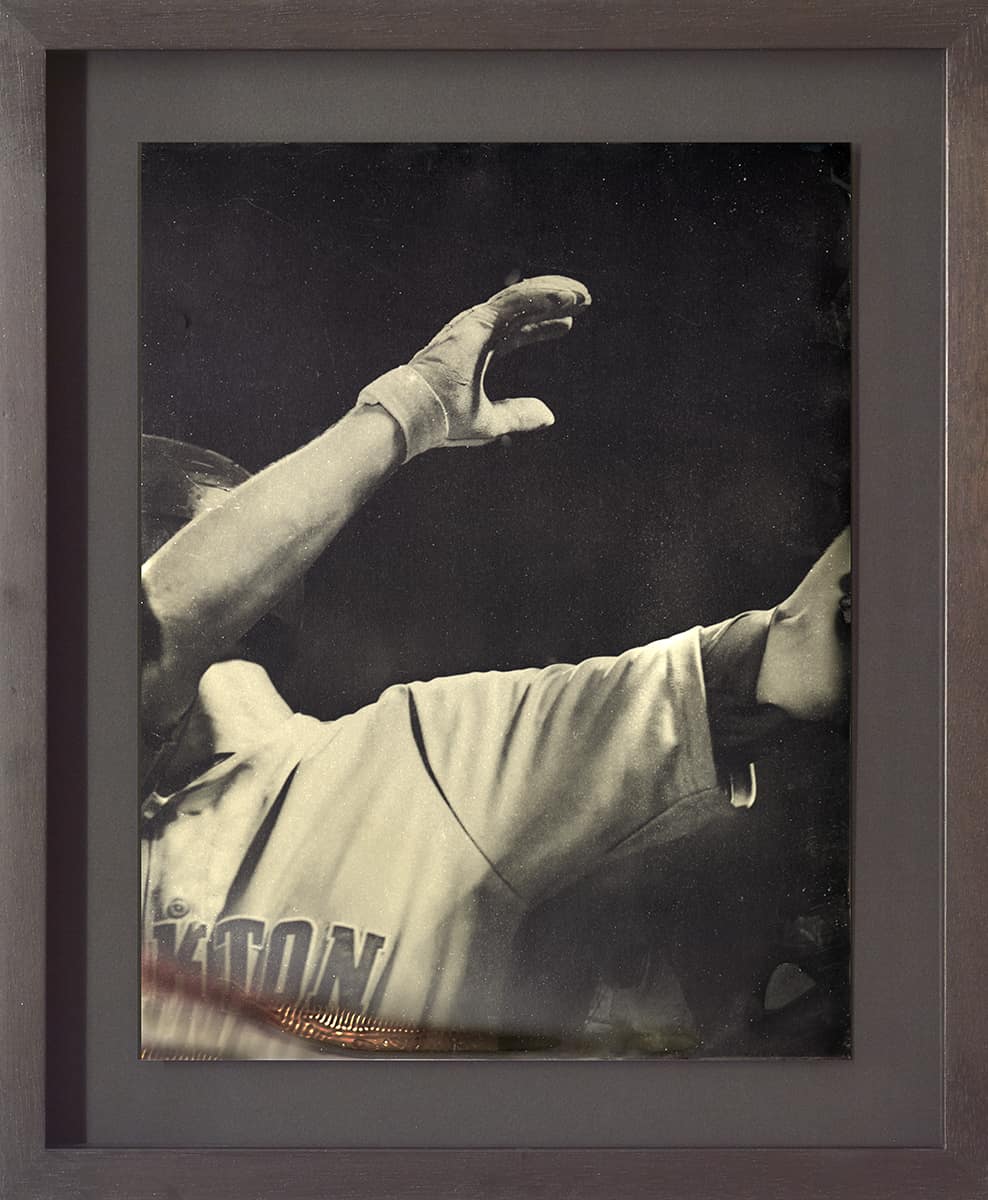

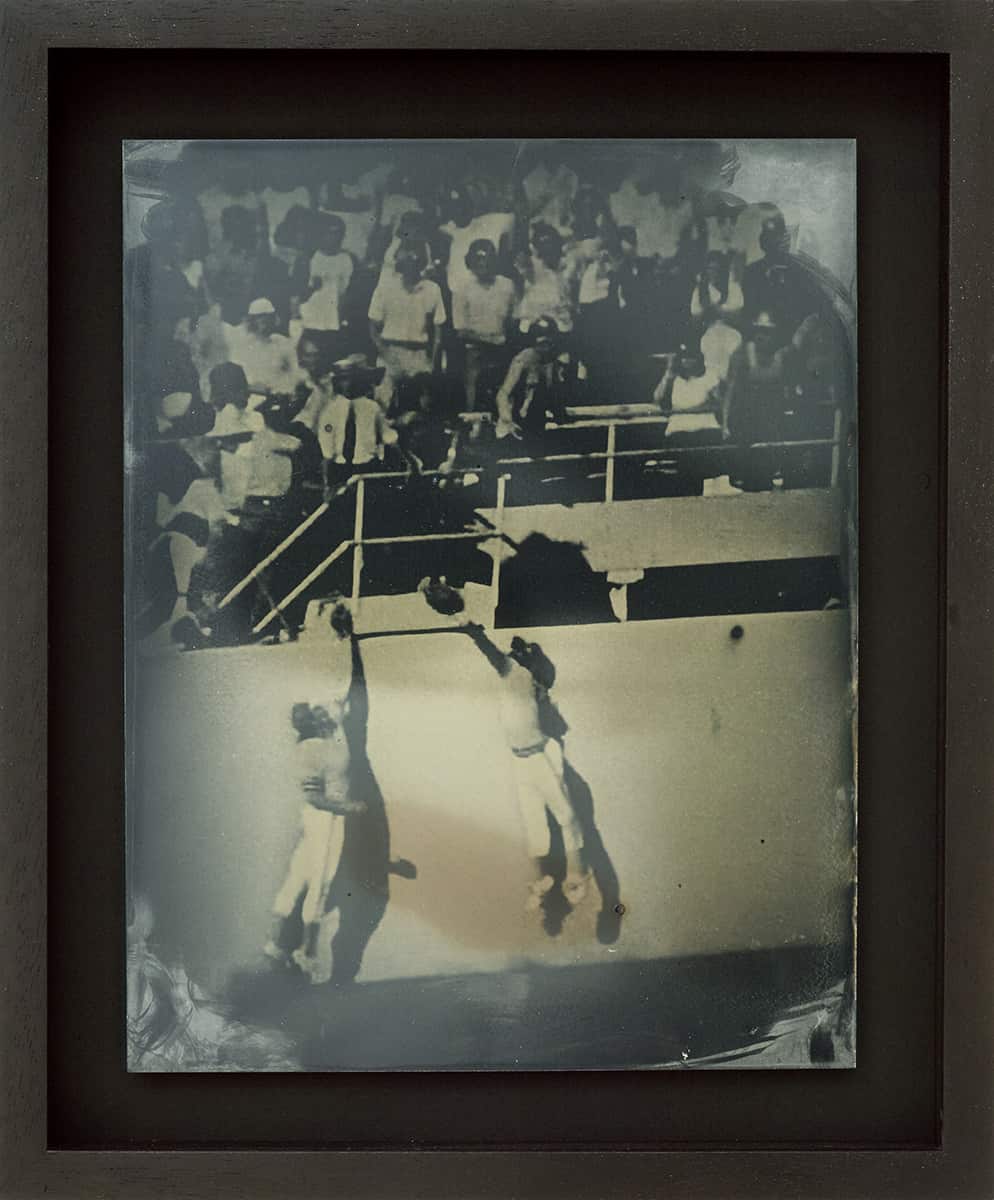

Yeah. Thinking about kind of process, one of the things I was struck by was the use of the tintypes for the Fantasy Life series.

Yup.

Initially you were shooting on a more conventional system, right?

Well, you know that project lasted so long, people ask me, “What were you using?” and I’m like, “Jesus, I used everything.” Basically, it chronicles the transition from analog to digital. My action shots were looking like everyone else’s.

From Running – Tabitha Soren

Mmhm.

And I knew I had to have action shots, but when I showed a book editor my selects, at some point in the process, he said, “These are all great, but you have no pictures of people actually playing baseball,” and I thought, “really??” I couldn’t believe it. Because I had taken them, but they weren’t…I didn’t feel like they were art.

Right.

So when I was doing some research about the beginnings of baseball, because I’m not a fan, I didn’t know anything about it, I saw the date of the first baseball game, and it was only a few years was years after photography was invented.

Ahh.

So I thought, “Well, that’s a nice connection,” maybe I could take…I’ve seen tons of portraits with tintypes, maybe I can take some action shots, somehow. And that could be the way I incorporate playing baseball into my project, and it wouldn’t look like anybody else’s.

How long did it take you to satisfy yourself with that? I can only imagine how hard it was.

Oh my god, I still have metal plates all over my darkroom that I really should just get rid of, but I haven’t had time. Piles and piles of leftover tintype mistakes that went awry in some way. I mean, they’re so heavy, and there’s masses of ones that just didn’t come out. I don’t recommend it. It was hard!

I’ve seen it.

The mistakes are all so beautiful, but I had to actually, there was a part of me that felt like it was amateur, like when I touched the thing, and it had my fingerprints on it, and it wasn’t dry all the way, or I shook the emulsion too hard, so there were bubbles that never went away, on the plate. I just made every mistake you could possibly make, and I actually ended up selecting some of those that I had discarded earlier because I felt like they brought you into the arduousness of trying to make it in the game, trying to make art, just the struggle of life, and I feel like that shows you, it wasn’t perfect and they were more interesting to me, as a result. I’m working on a book on that project with Aperture right now.

From Running – Tabitha Soren

Oh, that’s great!

It’s so exciting to find…when we were talking about the pictures, some of the ones that are kind of a half-mistake but I think are kind of really messed up and important, they really liked, too. So it’s been fun, they scan very differently than they exhibit, so it’s a whole other consideration.

Right.

The scans just show up every imperfection and I think they look really punk rock and cool, I think they’re very precious, this beautiful object that harkens back to the early days of photography, and is very classy.

Sure.

Aperture is picking all the punk rock ones, as punk rock as baseball can be, that’s not a very high bar. I mean, me sitting around with athletes, I never hung out with jocks, I was a cheerleader in high school…

(dramatic gasp)

But all the crazy girls were the cheerleaders, it wasn’t the typical…the way the cheerleaders were in my junior high, which was in the South, that was very beauty queens, it was…the popular crowd.

Hahaha, right.

Whereas in Virginia, the cheerleaders were African American girls that taught me how to dance, and we were just very weird.

Hahahaha!

But I never hung out with the athletes, ever. So, to spend thirteen years with these baseball players, I still say, “Go put your outfit on.”

“It’s a uniform! Could you give us a little dignity!” Do you follow baseball? Are you sporty, at all?

No, no, I’m a huge nerd.

I mean, there is a lot of benefit from knowing what’s going on in the game. I think my pictures really separate themselves from the world of sports photography because I didn’t know anything about the game, but there were so many shots I missed because I didn’t know. I mean, you know, the team was ahead, and they don’t play the bottom half of the last inning, I’d be all ready for this victory shot, and I was like “wait, where is everybody going, I thought we had another inning?!” That happened a lot.

From Fantasy Life – Tabitha Soren

But I think, like you mentioned before, you know, not knowing, that’s your specific point of view. No one can take those shots but you.

That’s true, that’s true. And all the sports photographers, for the most part, there were a couple of times when I was shooting film, they scoffed, “Uh as if, you won’t get anything.”

Hahaha!

But most of them were…it’s such a precise business that if I told them which player was mine, they’d say, “Well, he’s going to be on the mound at this time, so the best place to be during the game at that time with the light behind him is this seat.” Like, thank you, because I’m not here for the whole season, I’m here for one game. That just saved me a lot of trouble!

Ha! They’ve got it all dialed in.

Yeah, but they have to, because they have to get the home run, they have to get the strike out. I had the luxury of following like one or two players on the team, most of the time, which also, if the ball didn’t come to them, it was really boring. But it was a lot easier than trying to cover all of the action of the game.

And it’s like you said earlier, it’s about going deep, rather than just skimming the surface.

Right, while one is a money making job, and the other is art. Haha, right?

Hahaha, totally.

Like, thirteen years of credit card bills.

Right, hahaha.

Every so often I got an editorial in Sports Illustrated, New York Times magazine, who else, ESPN, there were people who helped me pay for it along the way by publishing the pictures, but I certainly couldn’t count on that.

Right. It makes me think about this question: as someone coming from another career where you had you know, a level of name recognition, did you feel like you were working, against that, in some way? That…

Being downwardly mobile?

From Fantasy Life – Tabitha Soren

Well, no, I mean like…

My agent calls me her most downwardly mobile client.

Hahaha, but you know, where people had one view of you in their minds, and was there kind of a sense of…

I am dealing with that, but only because there’s no way around it sometimes.

Right.

It’s not everybody, I mean certainly there are gallerists of a certain, you know, it’s only people of a certain age.

Right, right!

TS: And most of the response is positive, but there is some head scratching, but it’s not something that I sought out purposely, it just is part of it, part of changing gears. And I think there’s a lot of other people falling out of love with one career and into love with another. At least, those of us who are moms, I feel so blessed. I do feel like there’s a certain amount of bravery involved, because I would be more at peace if I only took care of my three children.

Right.

Eh, that’s not even the right way to say it, because I would be going out of my mind…

Hahahaha!

But there’s something, it’s simpler, it’s simpler to not have to juggle.

Right.

Pick one or the other, either head of the law firm, or have your identity defined by your domestic sphere. Perhaps just because of who I am, even if I didn’t work as a journalist, that does not make me completely happy. I do like the mix, but it takes a lot of planning, it’s a luxury that I have childcare, you know, a lot of things I have a choice in, that other people don’t. I feel lucky, but I also feel brave.

From Fantasy Life – Tabitha Soren

Definitely. And you talk about changing careers, I feel like that’s far more common now. Most of my friends are on their second, or kind of third careers. There are so many more options, as we live longer, it seems a lot more, both acceptable and common for people to, like you said, change gears.

Yeah, I think so, too. I think that’s the key, what you just said. It’s pretty normal, Hannah Rosen, I don’t know if you know that writer, she just wrote something really good about going from print journalism to working on the podcast Invisibilia.

Oh yeah.

The title was “Screw Mastery.”

I bookmarked it yesterday!

That resonated with me. I mean, there is no mastery in art in the end, right?

Right. After you’re dead, they’ll call you a master. I think that’s how it works.

Hahahaha, yeah, that is how it works.

I think, oh, there’s one last question, if you have the time.

Sure!

We ask this of all our interviewees: which do you prefer, the process or the result?

Ohh…

This is why we ask everybody, it’s a big one.

We’re assuming the result is the great picture, not the crappy one.

Yes, yeah, I guess in all things be equal, the good result…

There’s plenty of crappy ones, before you get to the great one, at least it is with me. I think I prefer the result. That said, the thing that I do prefer about art versus journalism is that I actually enjoy the process very much.

Ahh.

I lose track of time, I don’t get tired. But there is a certain level of stress and anxiousness in me trying to create whatever it is I’ve got in my mind. And I don’t have an MFA, I have learned technically what I need to know for each project, but each thing keeps changing, so there’s always a level of, “Oh my god, is this going to work?”

Right.

I just trashed a lens a couple weeks ago because I didn’t, I thought I was working with this thing called a Polaris, which allows you to take pictures of the sky without having star trails, you have to go to a dark site to do it, and of course it’s totally dark, you can’t see what you’re doing, and I clicked in one of the knobs and not the other, and as I was going to get some other piece of equipment, it just fell off the camera onto the ground, and crushed the lens.

(pained sounds)

So, I mean, that is not unusual.

From Running – Tabitha Soren

We’ve all dropped a lens…or three…

So there’s always, “Why is the flash going off? Why is the camera stand up? Oh my god I forgot to load the film,” there’s just, there’s that level of me having to worry about making mistakes involved in the process that makes me answer the result is what I prefer, because at that point, the hard work is behind you. The anxiety, the doubt, behind you. I’d have to say the process of making art I do enjoy and pay more attention to, it feels more fluid and natural than journalism, in part because I’m working by myself, and in journalism it’s always a team effort.

Yeah.

So there was all of that to deal with: other people’s personalities and strengths and weaknesses and politics, office politics. Not that it was a big hassle, but you know, you have other human beings, you have other things you have to consider, and most of the time I’m on my own with art.

Right. And just, actually, I’ve got one more question.

Sure!

As someone who was an interviewer, how do you find being interviewed now?

Well…one of the busiest, noisiest elements of my job, when I was a journalist, was doing interviews back then. The reason you know, people knew my name was because MTV’s marketing department had me do interviews with everybody under the sun, and every interview I did with President Bill Clinton was typed up verbatim by the White House, ever “umm,” “you know,” every mistake, and it was distributed to every White House journalist, every single time I had a sit down with him.

Oh god.

Yeah, talk about scrutiny…I was twenty-three or something?

Perfect.

Anyway, so I’m used to that. I like knowing what I think, and someone taking an interest in the stuff that you toil over, and think isn’t good enough and maybe it is, and maybe it isn’t. Having to explain what you’re thinking about the work I find super-satisfying, because most of the time you’re working in a vacuum, you know, nobody really gives a shit about art.

Hahahhahaha!

So you have to get to, interact with somebody who does is a huge pleasure.

Was your interest, as a journalist, in politics originally?

Yes, it was. I was always passionate about, as silly as MTV has become, back then it was really a perfect place for me to work. But the news division saw that I was serious about covering politics and when I got tired of old white men lying to me, I could go on the road with Pearl Jam or something, it was a nice antidote. And then when I got tired of the musician not making sense, or a rapper saying, “You know what I’m saying?” having to explain everything, “You gotta be real,” then I could go to Washington and get a longer answer.

Hahahaha, you’re killing me.

So in my twenties, that was pretty good.

Do you keep up with politics now?

Yeah, totally! I mean, I live in Berkeley, what do you want from me, you can’t escape it here! I mean, that’s one of the reasons I like it so much, Berkeley could have a better sense of humor, but it’s intellectually challenging. You have to explain yourself, and I think that keeps you honest.

Yeah, definitely. And I think that does it!

From Surface Tension – Tabitha Soren