Interview 080 • Dec 18th 2022

- Interview by Lou Noble, portraits of Shannon Perich by Lou Noble

Links

Foreword

When the Smithsonian reached out to us about their new exhibition, we jumped at the chance for a conversation. We've never interviewed a curator before, found that idea very enticing, but we also flipped over the opportunity to discuss Richard Avedon at length.

Shannon Perich, Curator of the Photographic History Collection at the National Museum of American History, was the perfect person to speak with and to lead this exhibit. Our conversation was thoroughly engaging, we could've talked to her all day! We talked about how she goes about developing an exhibit of this size and depth, Avedon and his legacy (which is still vital to this day), and how her journey led her both to the museum and to Avedon.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

Let’s start with, why did you decide to have an Avedon exhibition right now?

This exhibition has been in the planning for a long time and it’s one of three exhibitions that are opening at The West Wing of the National Museum of American History, on the third floor. This is the inaugural exhibition for the new gallery space, the new named gallery that we have.

It had different iterations before the pandemic, but during the pandemic we honed it. I’ve been at the museum for 26 years and I’ve lived with these photographs for a long time, and thought about them differently over time, as one does with the privilege of being a curator in a space, and in a collection. This particular exhibition was a proof of concept. A concept of how to do a high-impact show with a modest budget.

Avedon’s work is so compelling. The National of American History’s collection is about the history of the medium, we’ve been collecting since 1896. We’re a very old collection. We have to figure out a way to differentiate ourselves from the other 700 collections at the institution. I’m not making that number up. That’s a real number!

Wow!

I’ve been thinking about the photography collections here, thinking about these photographs, writing about Avedon periodically over the course of my career, thinking about why photography matters. And in this particular moment in time, you know, maybe even better than I do, that we don’t understand print culture in the same way.

Mhmm.

So thinking about the power of his photographs and why we still love them, why we need to tell people he was meaningful, and these photographs were meaningful. It really comes down to the print culture, it comes down to the fact that these were lived images. What we’re showing are rarefied art objects he donated to us in the 1960s that he printed, that he signed, that have a particular look because that was his aesthetic in the mid-1960s, but it’s not enough just for, I think, us to put stuff up on the wall and say, “look he’s important!” I wanted to show how we live with photography, and that not all photography is created equal. And by saying that not all photography is created equal, that means we can lift some work up as we live with other kinds of work. The exhibition is focused on the ideas that came, in a way, from the first exhibition that we hosted in November of 1962 of Avedon’s work. The Smithsonian gave him his first one-man show. Over at the Arts and Industries building.

Right.

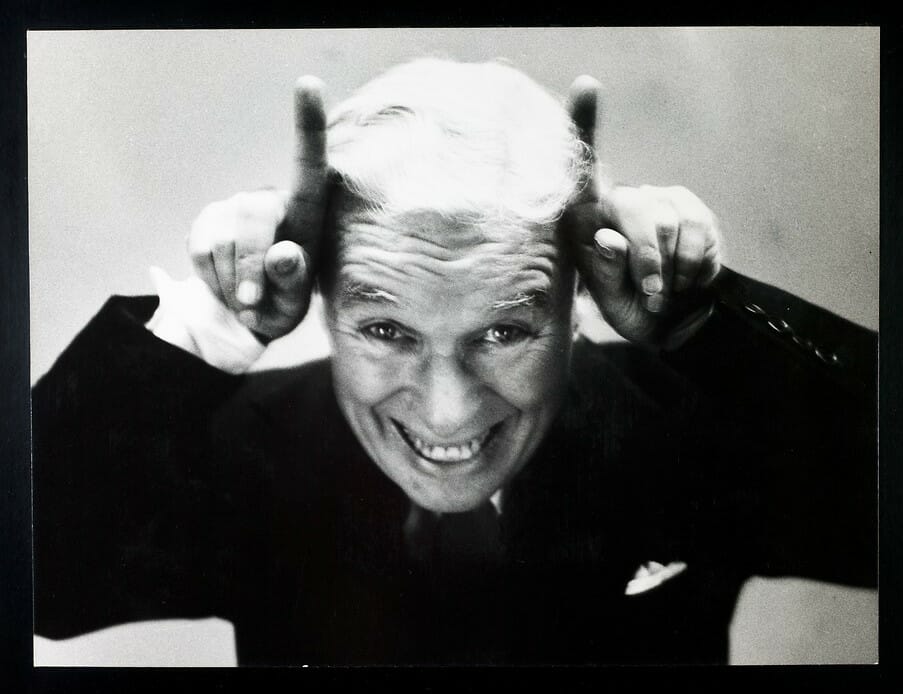

The objects that are on display here are from his second and third donations to the museum. And in that first exhibition, and we show one of the announcements in the exhibition, he literally push-pinned things to the wall. No glazing, no framing…the Charlie Chaplin picture was a mural six feet wide and he had 35 mm cutouts that, from a contact sheet, that you had to walk up to. So, there’s this really interesting physical tension.

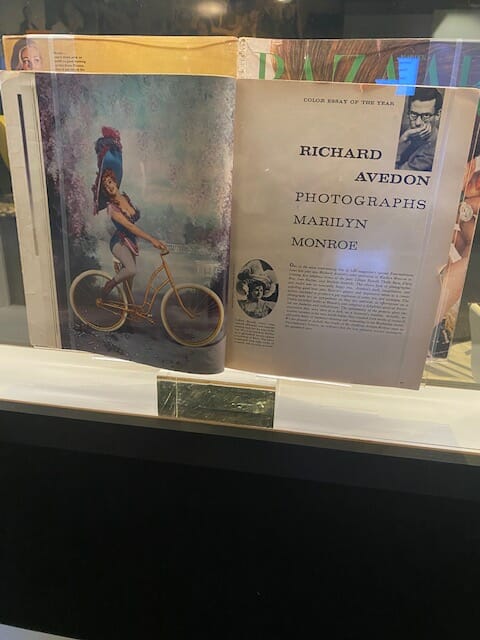

There is also, as you’ve seen in his books, a psychological tension and a political tension by who he puts together. So this idea that he was associating people and images on his own, and different portraits together is not my original idea. Riffing off of his first exhibition, looking at what he did, in Nothing Personal with James Baldwin, and you don’t do anything with James Baldwin and think it’s apolitical, you know, it gave us space to say, well, these photographs mean something and they meant something more than cool pictures in Harper’s Bazaar, wherever they were appearing. And the idea that these pictures appeared in magazines, that people could actually hold them was super-meaningful to me. The 1963 issue of Harper’s Bazaar has a spread in which Avedon’s portrait of James Baldwin appears, it’s the one where he’s sort of leaning and looking. (see top of page)

Charlie Chaplain, 1952

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, All Photographs by Richard Avedon

Oh yeah.

It accompanies an essay called “A Letter From a Prisoner”, and I read the essay because I’ve seen it online and I knew the spread. But when I physically held those, and Baldwin is looking at me, waiting for me to get through the essay that he’s just written that he’s addressing to me, because he says, “Dear white reader, you’re responsible for racism and what are you going to do about it?” Especially in 2020, that was such a potent moment. So this exhibition is this very personal effort of mine…Baldwin says in this essay, “you can’t blame the past, and we are the time.” Well I work in a history museum, so we’re all going to be thinking about that, right? What does it mean to be “we are the time,”…we do critique the past.

I see Avedon and Baldwin are using their platforms of literature and words and photographs and magazines. My platform is this exhibit, so how do I help lift up these questions that they already were working on and percolating and living with through the photography? How do I lift that up out of what we know to be Avedon’s body of work to wrestle with today? And how do they matter today? This is a very long answer to your question. I apologize.

No, this is exactly what we want.

Okay! Yes, the exhibition is multi-layered. The photographs are set off of the wall in a very personal way, they’re lit so beautifully that they glow. It’s extraordinary what our lighting designer did to make these things, they really do feel luminescent and that you can have a relationship with the the art of his and they’re set off of this gorgeous, curved wall, it’s the sexiest wall in the building.

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History

There are a couple of other things that we did in the exhibition. The murals are made from non-Avedon photographs that we sourced from our own collections, from the Sherman Indian School, from university collections, Library of Congress, and some other individual photographers that we sought out. And the murals, we literally ripped pictures and created a collage. So those murals serve as a visual background to what Avedon was working against, like the other types of photographs, but it’s also thematic and to remind people what else was going on in the moment. If it’s about music, the four musicians we show, they have a relationship with each other. They are in competition with each other, but they’re also in competition with everything behind them.

So there are multiple ways to experience the exhibition. And we really made this to be an experience with Avedon’s photographs and knowing that this is part of a new floor, it is its own thing. It is its own entity, but we also know that folks are coming from this other major exhibition. And the themes of that exhibition about American entertainment were also on my mind, and what they’re experiencing across the hall, is a very big experience, it’s spectacular. It’s folks finding their way in culture, and seeing they’re part of a bigger picture. And this exhibition turns it around so that ultimately I hope people see through Avedon’s photographs and the way that he has stripped away flattery, the way that he doesn’t have a lot of other information telling you about the subjects so that you have to engage with people, you have to look them in the face. You have to look at their wrinkles. Look at their hate, look at their sadness, you recognize that even though they might be celebrities, they’re still people.

Right.

That they’re operating from a place of emotion and psychology and their contributions to culture are framed by that and shaped by that. So when we look at our own participation in culture, we find we also have power because we feel those things and know those things in a way, too. So I was in awe…this is a long way to say that I’m not asking people to like Avedon. I’m not asking anybody to like the individual subjects. I’m asking people to engage with what they were feeling and where they were operating from and how they engage with other people of their era.

We used an exhibition philosophy called IPOP, and it stands for Ideas, People, Objects, and Physical. And those are the ways that most of us will have a primary way that we want to engage with exhibits. This is a heavy idea exhibit, most of the exhibitions at American History are chock-full of objects, lots of labels to read and stuff to look at, and this is very much about stuff to look at, but I’m not asking anybody to read unless they really want to. Which is a relief, I think, for a lot of people.

Not our audience, I hope!

And to not be forced to read. So when you’re standing looking at the photographs, the label you see on your right is about the photographs and our exhibit is fully bilingual and it’s accessible, there are visual descriptions as well for the visually-impaired. Our imaginary audience that we wrote to were teens who were 14 to 18. We didn’t make this exhibit for them, but that’s who we were thinking about so that we all had the same group of people in our minds. As a generation who are asking themselves some very essential questions as they emerge into their adulthood, and thinking about their place, the questions that we found were suited to that exercise, but we also know that they don’t always read. So there’s lots of access points.

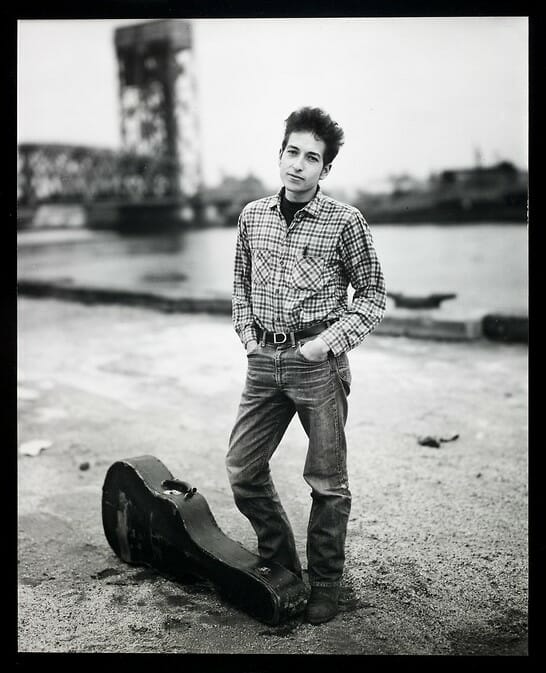

left: Judy Garland, 1951 right: Bob Dylan, 1963

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, All Photographs by Richard Avedon

How big are the independent portraits here?

The prints themselves, the blackboard that you see, and the framing is 28 by 28 inches. And these are really interesting because the entire collection over these two gifts were mounted by Avedon, dry mounted on these black, shiny boards. I’ve never seen that done anywhere else like that. He did that specifically for us when he made this donation. And when he made this donation, he also donated the negatives at the same time.

It brings up the question, how did you decide to limit it to that ’46 to ’65, period?

That’s the date range of the objects that we have, for the most part. This is, these are all his Harper’s Bazaar years. So at ’65, he leaves Harper’s Bazaar and then moves towards Vogue.

Do you think about the other exhibitions of similar work of the same artist when you’re putting something like this together? Are you in conversation with other Avedon exhibitions?

In a way. I don’t feel like I’m competing with anybody because I’m in a history museum and our audience is different than who would be going to Art Museums, not exclusively, but sometimes. And most of the shows I’ve seen of Avedon’s work, it’s very big. It’s about the individual subjects themselves and I wanted to respond to the way he was thinking about presenting his work in publication and in print, and putting individuals together to create that kind of synergy, so that they would resonate with each other. That’s why I’ve grouped them this way. And I don’t know that I’ve seen other exhibitions that do that. I also wanted to lift up the importance of the print aspect and the print culture aspect. He’s a culture maker, but he’s also influenced by culture. I wanted this to go a little bit back and forth. I wanted to remind those of us who love Avedon’s work and are so engaged by it that without print culture, he wouldn’t be who he was.

Totally.

He himself became famous because he was the subject of articles. He was in print himself, his work was in print and it wasn’t just print, it was the fashion work but also in 1950, 1954, he won two prizes for advertising for Rinso laundry detergent, and Pepsident toothpaste.

He really did influence the way that we see, and, you know this from all the photography that you write about, and think about and publish. This time frame of print in magazines taught us what extraordinary photography looks like.

A lost art.

It gave us, culturally, an aesthetic to work with. And it taught us that we could be cerebral around photography, and that not all photography is sentimental. I think that’s part of what I wanted to lift up here, we were talking a little bit about his style of portraiture. And so much of what we see today is fast. It’s quick, and it’s really about the surface. We want to look good. We want to show ourselves in our best light and the cool stuff that we’re doing. And we have all these filters that we use. I wanted to strip that back and get back to the essential questions of what a portrait is.

Mhmm.

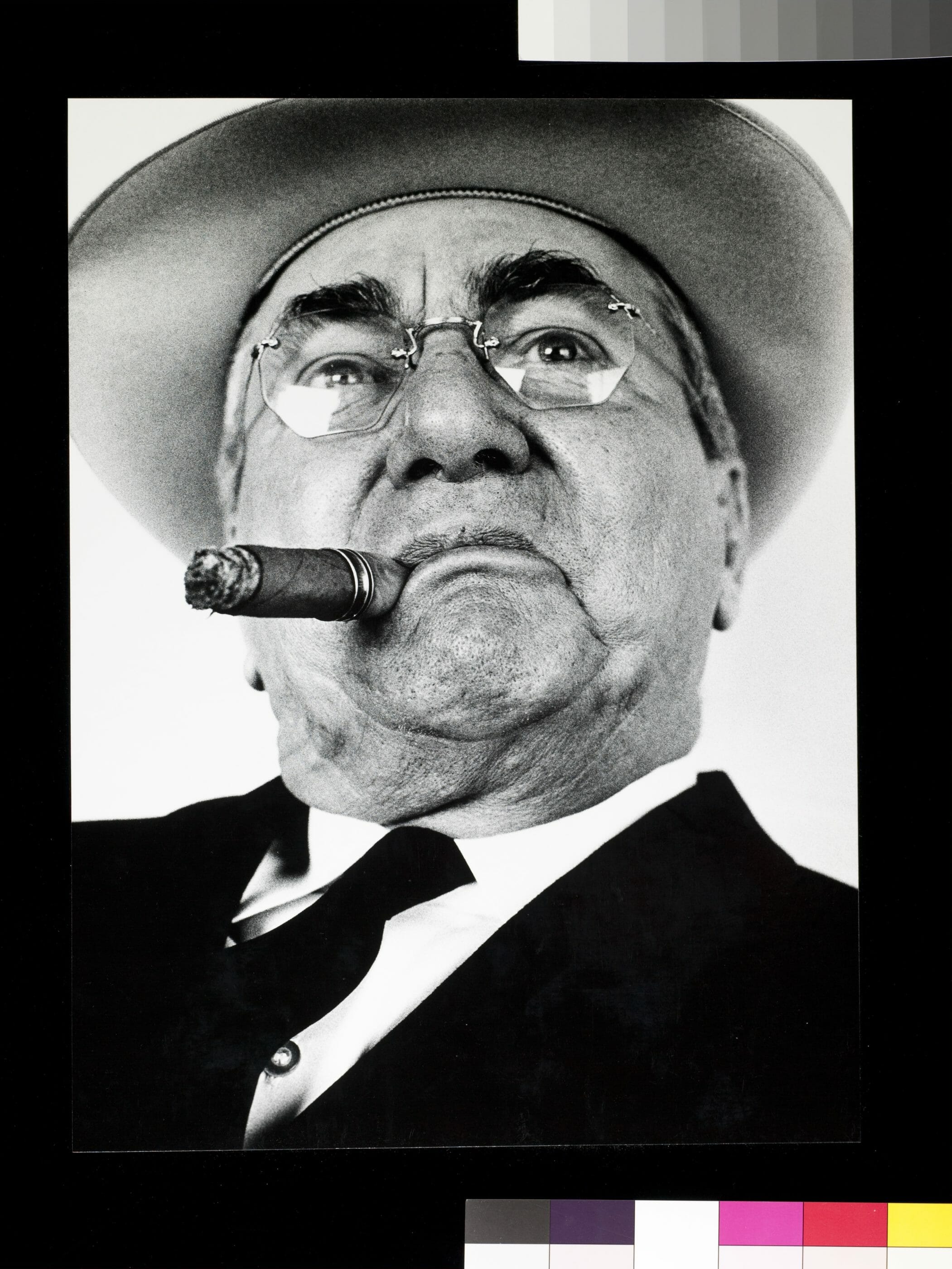

And that is possible here. In many of the photographs you can see Avedon actually reflected in the sitter’s pupils. And there’s this really heady question that you can think about, or one might think about: what does a photograph reflect? Who does it reflect, does it reflect the photographer, does it reflect the subject? What happens when you’re looking at a photograph and you see yourself in that reflection, whether it’s the glazing or, you know, your own cell phone, when you’re taking a picture of it, you’re engaged with it, you see yourself in it. So when you see photographs like that of Leander Perez, who was an extraordinarily racist judge in Louisiana, and you see that Avedon allowed himself to be reflected in this very hateful man’s eyes. What does that say about what our humanity is? What does that say about Avedon and recognizing himself? Somehow in this extraordinary photograph of a man who hated him, right. So I think there are really existential questions about what does portraiture mean, when you can see yourself in it. The wrinkles in the faces and Dorothy Parker’s bags under her eyes.

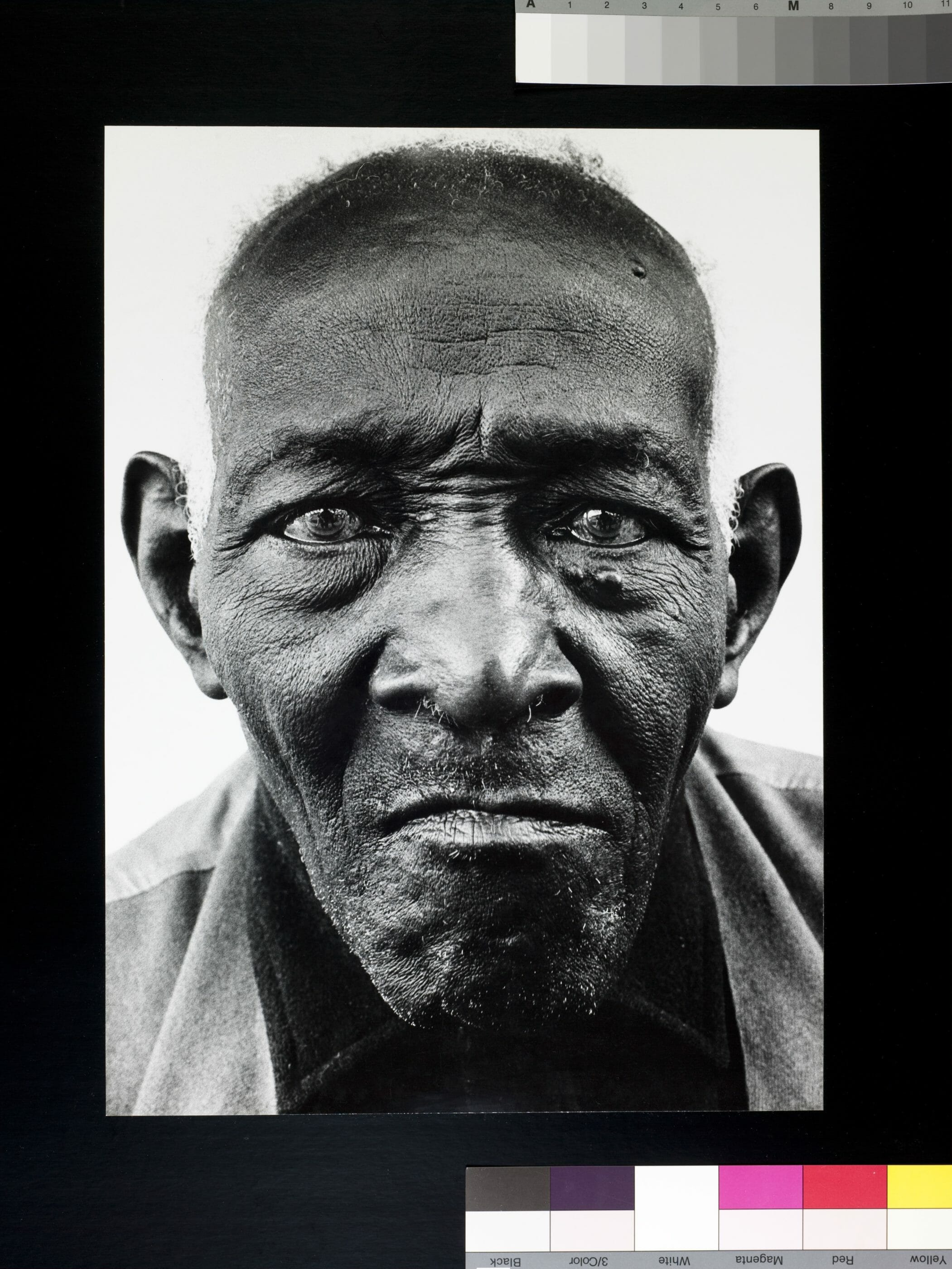

left: Judge Leander Perez, 1963 middle: William Casby, 1963 right: George Wallace, 1963

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, All Photographs by Richard Avedon

Right.

How do people read us when they see our portraits, and are we willing to be that vulnerable.

Where do you place Avedon in your personal pantheon of photographers?

It’s hard because I’ve lived with him differently than I’ve lived with any other photographer. I don’t think that anybody, after Avedon, can…make a photograph that is unflattering. Even with the same intentions, even with the same kind of extraordinary skills, they can’t make that photograph as powerful. Because once he did it, the needle was moved too far. He stripped it away, he made it okay to show people and all of their icky humanity and validate them for whoever they were.

There’s an element of transgression, of intention to it, that there wouldn’t be that in subsequent photographers.

Yeah, I think so because everybody would know the game after that.

You spoke about tension. Is that one of the things that has drawn you to his work, over the years?

I think so. This notion that photography has to be pretty and comfortable really goes against…that’s the tension in collecting photography in a history museum. So much photography is about the aesthetic and the aesthetic having some aspect of graciousness to make the viewer comfortable. History is not comfortable.

How does photography take and how do photographers take all of the tools that they know about the technology, about how lenses work, about how papers work, about how composition works, about how black-and-white works, about how color works. How do they take this huge tool box and put these pieces together magically, and their magic, and their individual ways to create an image that resonates not just for them, but resonates with their community, culturally, historically, and who does it represent, and at what point. It represents all of those things. I think the best photographs are like an atom that has all these electrons swirling around it.

I can see that.

An atom that has all this energy and different ways to access it. And Avedon’s photographs, for me, really do that. They ask so many questions about what photography is, but it’s also what is photography in a particular moment in time. You asked about the pantheon..I am responsible for almost a quarter million objects, so that’s a lot of babies to think about.

Oof!

But he really does serve as a benchmark, that the needle was moved and there was no coming back from that. So again this notion that he is of his time and influencing the time, that’s the pinnacle of where I think high art exists.

James Baldwin (1963)

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, All Photographs by Richard Avedon

Where do you start when you’ve decided to put on an Avedon exhibition?

I actually start with paying great attention to titles and dates. And if the photographer has assigned an object that information, then I take it pretty seriously. And for all of these photographs, my entry point was the date in which they were photographed by Avedon. Why was this person picked at this moment in time.

I see what you’re saying.

And then what was their life about. And then where does it appear. So, it’s what context was it seen in, how many times was it seen and who was it seen by. Where was it published, how do I know what the impact of this photograph was. I might have a personal response to it, but that doesn’t mean that I understand the photograph.

It’s a lot of research, figuring out where it appeared and who saw it. And was it distributed, who else said what about it at the time. And thinking again, you asked me at the beginning of this conversation about why like this and why this topic, and for me, I want to say something different about Avedon. And from sitting in my chair and collections in a history museum, I have a brilliant chance to ask different kinds of questions of the photographs that I steward.

Do you go through the space and try to see how it inspires you, do you go through the collection first and then try to match some of it to the space?

In this case, it was actually the idea first. And then there are all the institutional parameters of the space that I was able to use: how big was it, how much money did we have. Those kinds of things. Then it was an extraordinary collaboration with a brilliant designer to say, how do you put 20 photographs in a 4,000 square foot space and make it feel intimate and have a fantastic experience, working with that designer to manifest all the ideas and things that I know about Avedon in these photographs and the time period and print culture, to organize it in a way that makes sense.

And this is, I think, a rare exhibition in our building in which it really like stepping into my head to see how a curator puts information together. And what kind of questions I asked of myself that I’m sharing with you to share with you why I think they’re valuable and interesting and compelling. But unlike many exhibitions, I don’t have the answers. I really want to give space for the visitor to make their own decisions about what information they want and how they want to put that information together for themselves.

Looking at this exhibit, it’s very much an exhibit that requires time and effort to process. Much like Avedon’s works, it’s not something you just look at and move on from, it asks for effort. It rewards your attention.

Oh absolutely, absolutely. Behind a curved wall there’s a living room. We’ve created all of these spaces for people to sit and talk and reflect and think about. At the very end there are three tabletop activities in which we ask people “what is a portrait?” and invite them to come to explore that there are multiple ways to make portraits, depending on whoever they are for, and why you’re making them, what do you want to say and what opportunities do you have. So it really is meant to be a reflective, contemplative space because I think, for me, the most powerful grouping is what shapes your moral compass.

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History

Mhmm.

Because this is the this is the elemental question that we have to live with and cope with on a daily basis: who are you and how do you make your decisions. Who are you going to listen to you when you move through the world? I don’t know, that’s too big of a question to, you know…

Indeed!

It’s a life, it’s a journey to answer that question, but it is the most essential in American culture, today. It’s just to say, really, who are you and how are you making these decisions that you’re making.

If you see someone in your exhibitions who just kind of walks through the whole thing in a few minutes, do you feel a disappointment?

Not really. I’m glad they chose to be in my space. I’m glad they chose to move through it. We have around 4.5 million people who come through here a year. I have no idea how many people I impact and I don’t know how long it will stay. I mean, you know, you’ve seen something in a shopping mall, you’ve seen something in an exhibit, you see somebody on the street and it lingers with you for a long time. And I hope that this exhibit will create one of those impressions that lives in people’s brains for a long time, that they have to keep coming back to, whether it’s a single image, whether it’s an experience, whether it’s sitting in the living room, looking at magazines from the era. And I think even just passing through, you can’t not have some kind of experience. But I can’t control how people respond.

For sure.

Just like a photographer. We use all the tools we have, we make our best judgment, and sometimes we get it right, sometimes we don’t. But from what I’ve seen, I think it’s going to be a place where people are stilled and contemplate.

This is something we normally ask of our photographers but I think it’s appropriate here. Do you prefer, in curating an exhibit, the process or the result?

I love the process! What you’re seeing on the wall is a tiny sliver of my 26 years of thinking about and wrestling with and researching and struggling with this work. I don’t take it lightly that I have a platform. I don’t take it lightly that I’m a federal employee and that I’m working for you and on your behalf. I don’t take it lightly that I’m only the seventh curator since 1896 to steward this collection. I inherited a collection. I’m leaving a legacy for another curator to have to contend with. So when I’m thinking about this work, it’s not just this moment of exhibiting it. This exhibition is only one blip out of the history of this collection.

These photographs will be reimagined it another way in 20 years, 50 years, 100 years. So this exhibition is a way to put a thumbprint down to say, here we are right now. Here’s why this work matters right now, in this space, this space meaning the National Museum of American History on the National Mall. We live between the White House and the Capitol. These decisions that are made and debated between those two physical spaces, right. The national news is our local news. There is a weight to the physical presence of what this collection in this building means, in this space.

I think when you’re here, you feel that as a visitor. Visitors come to pay homage to what it means to be an American. Whether you’re an American citizen, whether you want to be an American citizen, whether you’re an undocumented citizen, whether you speak English or not. Whether your from someplace beyond our borders, people are coming here to understand, to the National Museum of American History. What does it mean. How does it happen. And for me, this particular exhibition has to answer some of those questions that people are seeking when they come here.

left: Louis Armstrong, 1956 right: Humphrey Bogart, 1953

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, All Photographs by Richard Avedon

How did you find yourself at the Smithsonian?

When I was an undergrad at the University of Arizona, where the Center for Creative Photography is, my uncle saw an advertisement for an internship in the back of Fortune magazine and told me about it. I applied, and I became an intern here in the Photographic History Collection. After five and a half years of being an undergrad, I switched majors my junior year to be a photography major, realized I was not a good photographer.

Oh no!

But I did two internships at the Center for Creative Photography, and my one of my first jobs was to disassemble a traveling exhibition of work by Ansel Adams and Paul Strand. I was doing the condition report and I saw the value of this small Ansel Adams and I was like, “well, that’s interesting, that is a really valuable piece of paper and my car is like worth like $400, and this photograph is worth how many thousands of dollars. What is that about, what does that mean?” I wasn’t upset or stressed about it, I was just really curious about it. And then on the Paul Strand side, I was holding the photograph of family from Luzzara, do you know that photograph?

Oh yes.

It took my breath away. And I knew in that moment, my epiphany moment, I knew I would never be a photographer of any merit and that I wanted to be a curator of photography. Trudy Wilner Stack was the curator photography then at the Center for Creative Photography, and I ran across to my advisors and told them I wanted to be a curator photography. She said, “Shannon, you’re crazy. And you know, you’re gonna have to take all these art history classes” and because I switched majors, I had enough credits in the art department in the College of Arts and Sciences to have a double major in Fine Arts with an emphasis in photography and an art history and then I did this internship. I came to Washington D.C., I had five hundred dollars in my pocket. If it didn’t fit in my car didn’t come with me, and I mean, I can’t imagine, I’m a parent now and I’m like, oh my God, would I do that to my children?

Ha!

I didn’t have a job. I didn’t know the people I was going to live with. I had rented a room, you know, all those kinds of things that you do blindly in your youth, but I knew I was supposed to be here for some reason. I went to graduate school at George Washington University and had the privilege of doing my doing my museum studies degree with all the museum studies class you’re supposed supposed to take, one of my professors was Lonnie Bunch, who’s now the secretary of the institution. He taught my exhibition history class, or my exhibition class. I only got a B! But that’s okay. And they asked if I wanted the job…some point after volunteering and interning, “there’s a job opening, do you want it?”

I’ve been here for 26 years, and no two days I’ve ever been the same. I’ve grown every day. I am a collection curator, which means that I spend a lot of time letting the objects talk to me and asking questions, and you open a drawer and two disparate things sit next to each other, and you think, “well, what is this energy about, do they have a relationship or don’t they. And what do they mean.” And this particular collection, because it’s so old, because it predates MOMA, it predates the National Gallery of Art. It predates the Met by decades and decades. There are extraordinary collections here because nobody was really collecting photography.

Mhmm.

And this collection was extremely important for many years. That’s why Avedon donated his work here, because in the mid-1960s, we were one of the most important photography collections. We have two daguerreotypes of Daguerre. We have the largest collection of William Henry Fox Talbots in the country. This is an extraordinarily rich, deep, international collection. And there’s 1,000 dissertations to be written. So I do what I can to make it all visible and bring these stories to the foreground.

Was there something that surprised you in the making of this exhibition?

I have come to love magazine photography of post-war America more than I ever thought I would.

Ahhh.

And I’m very excited to spend more time thinking about the magazines themselves, but also how photographers make their livings and negotiate their visions with their lives. And then what do we do as historians to honor all of that work that they did, that they produced, that they thought they had to do in order to make a living, with propelling their visions forward. And part of the tension here is: what is the legacy? How is the legacy created, is the legacy accurate enough. Does it speak to the actual hard work and decisions that were made, and the economic structures that photographers had to deal with.

But in post-war photography, and it actually starts really probably before the war, when print culture starts in the 20s and we start being able to produce photographs and text together easily in the magazine world. That time period has had so much more impact, I think it’s the most dynamic period of photography, first of all, even though there’s so much photography now, I don’t think we see avant-garde, revolutionary, compositionally, technologically changing tools except for now we have IR, artificial intelligence programs that are making really interesting images.

Courtesy Smithsonian's National Museum of American History

We could spend two hours on that, alone!

Yeah, yeah. That’s really our next thing to wrestle with. But, you know, it ask us questions like, what is authenticity, what is real, what’s not real, what is creativity. What is direction, what is a director. All that kind of stuff, but those are not new questions. It’s just how do we interpret those questions with that technology. But what really surprised me was the scope of work that Avedon actually produced and that we don’t know about. And discovering these awards that he won for Pepsodent toothpaste. While I understand some might not think that that’s the sexiest thing to talk about, it’s the reality and we as historians and as viewers and readers of photography, we get to look backwards and we know the end game, we know how it ends.

His death date is noted, but it’s not his legacy that I want you to think about, its this moment in time I want you to think about.

Yeah.

And that is something I think that we, as historians, and thinkers about photography, can spend more time, relishing all that, what it took to make something happen at a particular moment in time. And to recognize when you start getting into all that context, then you understand the nuances so much better. I hope that some of the excitement comes from being able to see the tension of a life that’s lived as a photographer, because in the moment, a photographer doesn’t know where their trajectory is.

Right.

They’re in the process of making it, and that process of making it in the moment to step into it for tiny second to say, Avedon was hearing, constantly about and thinking about what the Civil Rights Act was going to be, was it going to pass or not pass. And you know, what does that look like for him, how does he manifest that intellectual, moral struggle. He shows us that in those three pictures.

This has been fantastic, thank you so much.

Oh sure. I’m so grateful that you were willing to let me talk about it. I love it.

“(re) Framing Conversations: Photographs by Richard Avedon, 1946–1965”

Opens Dec. 9 at the National Museum of American History in Washington DC, and, in its current iteration, runs through Fall of 2023