Interview 094 • Dec 16th 2024

- Interview by Scarlett Croft, portrait of Scott Hunter by Rachel Spence

About Scott Hunter

Scott Hunter’s multidisciplinary practice explores the intricate relationships between humans and the environment, drawing on a phenomenological approach to reveal the often-overlooked impacts of industrial activities on landscapes. His work challenges traditional landscape photography by presenting alternative representations that question anthropocentric views and engage with ecological and industrial materials in innovative ways.

Links

Foreword

Scott Hunter’s studio overlooks the Firth of Forth. On the day I visited, the sea collapsed violently on the beach below - wind and sun shook and lit its surface together. The art deco building, somewhat incongruously placed in Kinghorn, is where Hunter has spent the past eight years developing his eco-conscious art. I first encountered Hunter’s work at The Saatchi’s Metamorphosis Innovation in Eco-Photography and Film (May 24th - July 28th) curated by Lily Waterton. The exhibition brought together a collective of artists seeking to produce a sustainable alternative to analogue film that did not rely on gelatine or discard toxic residues. Collectively, the works accumulated to throw the production of analogue film into sharp crisis. However, when I met Hunter, he assured me there was still space for analogue film amongst innovations in experimental photography.

Hunter’s work uses ecological and industrial materials to interrogate the legacies of industrialisation and mining on the landscape of Fife. Under the restraints of lockdown, he was unable to explore beyond a 10-mile radius. Contained to the environment he grew up in, Hunter began experimenting with techniques - from Soil Chromatography to Redox Reactions in a disused spoil tip - to capture the environmental degradation in his immediate landscape. We met to reflect on how he has developed his practice to render anthropological climate change perceptible through experimental photography.

Hunter’s work contemplates, and crucially, fuses, the practices of photography, science experiment and art. Imperceptible processes and eroded histories gather at the intersection of detailed environmental data and dramatic recordings of damaging environmental processes.

----

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

When did the sustainability of your artist production become integral to how you wanted to work?

I was working at a residency in Japan in 2018, and Typhoon Jebi hit, forcing the closure of Kansai airport. Many of my fellow artists were unable to get home. This was followed by a series of environmental disasters and catastrophes, and I thought there is an important opportunity here to reflect on anthropogenic climate change as an artist.

I had been working with landscapes in my work previously, in my series Coast Along. This work mainly used visual Haikus to process emotions, in particular my experience of grief, and was shot along the River Forth. People really resonated with this work, but I didn’t want to keep reproducing similar work and become stagnant. Working in a sustainable way, using plant matter as material for my work presented an opportunity to think and work sustainably.

What was your first experience working with plant matter to produce photographs like?

I did not experience immediate gratification. In the first week or so the negatives would often come out very thin due to overly diluted recipes. But even in the early stages I started to see interesting images, and I was excited about the results the process began to produce. I started keeping a record of which substances worked best to produce pleasing results. I was very specific, measuring out precise quantities of moss and jotting down notes with all of the records kept on a spreadsheet.

I began by visiting the Michael Colliery site, an abandoned mine on the coastline. Standing there, I observed a striking juxtaposition: a former coal mine at my feet, oil tankers dotting the sea, and wind farms on the horizon. This post-industrial landscape merges the past and future and it struck me that I didn’t necessarily have to venture any further (than my immediate landscape) to produce work.

How does your photographic-scientific technique create an intervention within anthropocentric discourses?

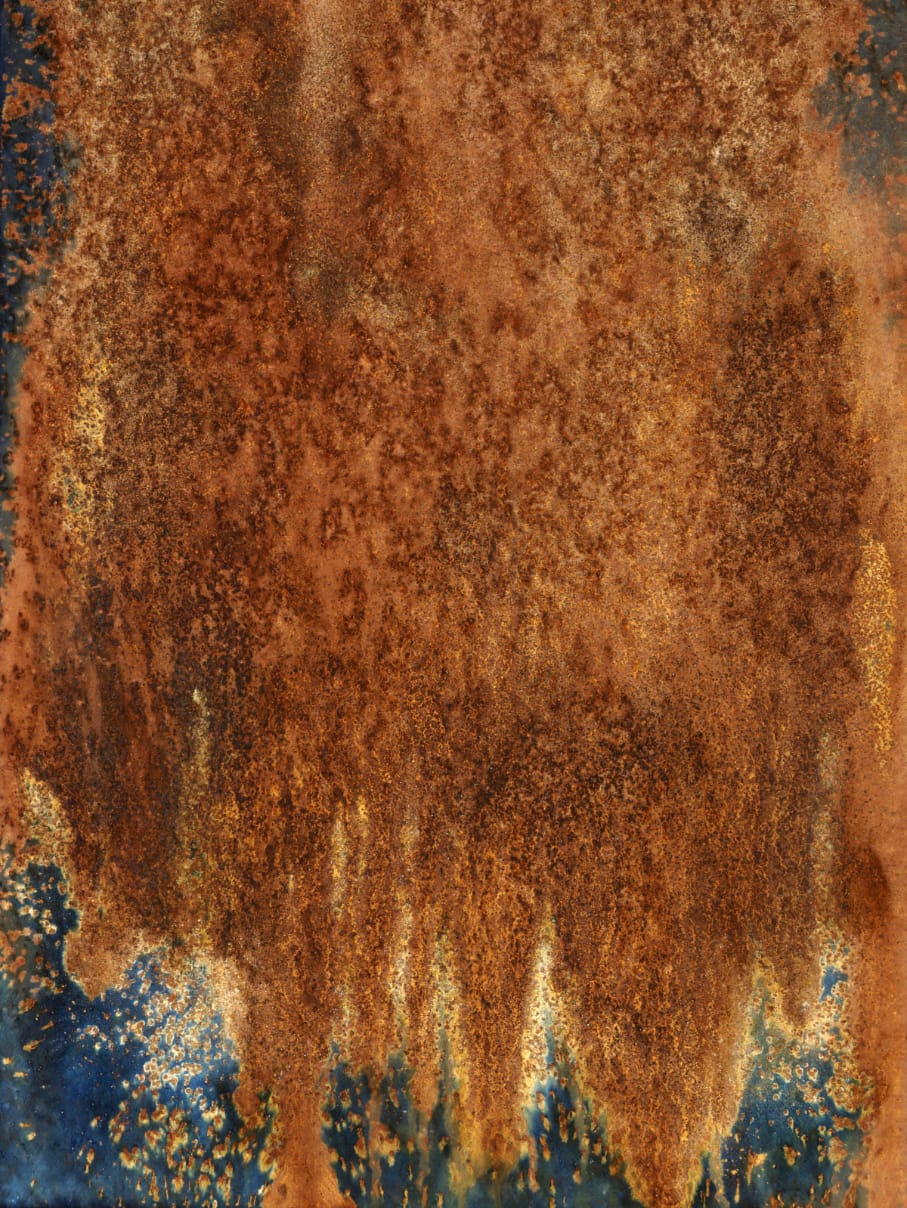

The intervention occurs in using the landscape. The non-human becomes an agent in the piece, and the works continually change. The criticism of the work originally was “where is the artist?” but for me – removing the artist’s hand, at least partially, was part of the point. For example, in my work Entropy the materials behind an invisible earth process (a redox reaction) are constantly at work and interacting. I cannot have complete control over the piece because I could not control the chemical process. Whilst I can change and alter the conditions, I am unable to intervene with the materials processes and reactions.

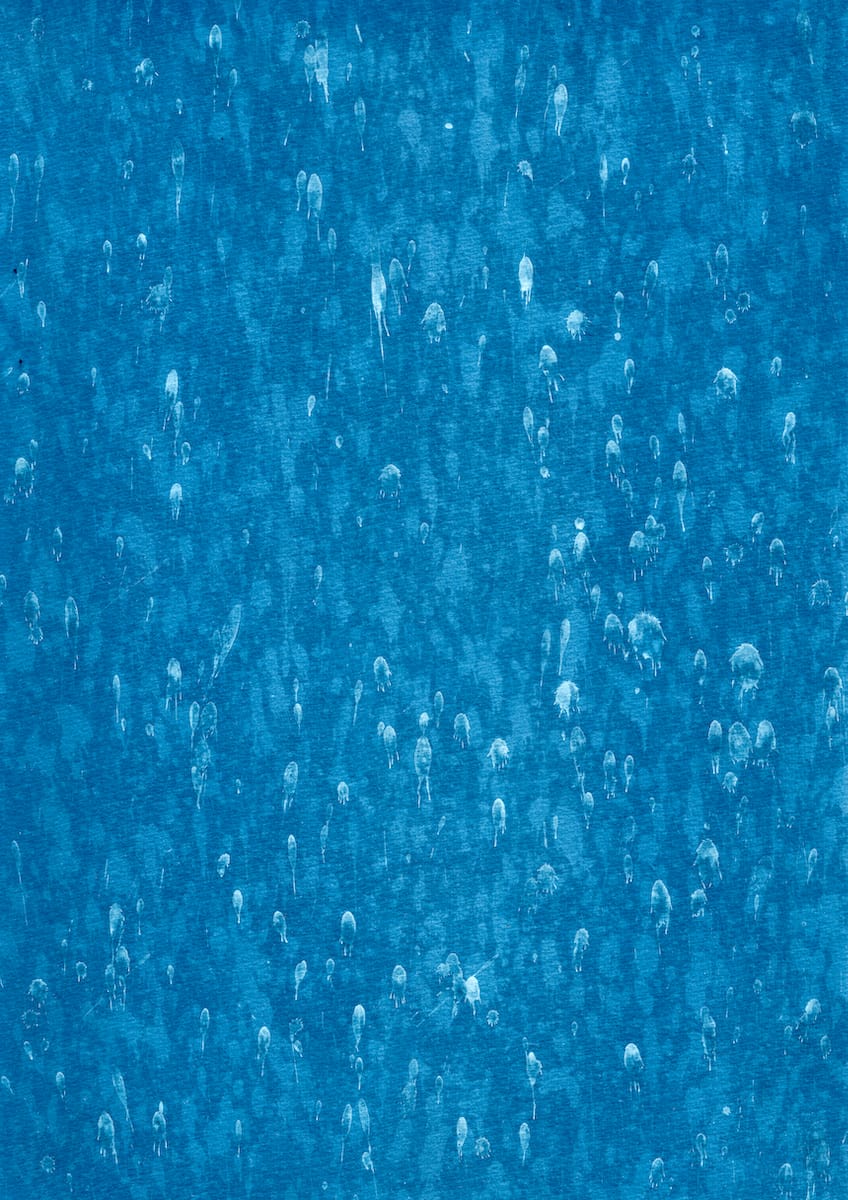

Similarly, in Precipitation, I wanted to acknowledge and document the increase in rainfall in Scotland, and the impact it had on Fife’s spoil tips, and therefore run off in the area. When I arrived at the studio, I would listen to the sound of rain on the roof and look out to sea to see how clear or opaque the view was. Over time, I became more attuned to whether the weather and available light would accommodate for creating precipitation “photographs” that day.

The landscape is then both the material and the subject, and the invisible processes that are usually illegible within landscapes are made visible in your work. With that in mind, why was it significant for you to ensure post-industrialised Fife was positioned as a “legitimate subject” of nature photography?

Firstly, it is important to me because it is the landscape I grew up in. I come from a mining county and family, heavily affected by the government’s sudden shutting down of the mines in the 1980s. There has been lots of work on the social and political legacies of this abandonment on the communities, but less on their environmental legacy. This landscape is immensely nostalgic for me, because it’s the space I used to play in as a child. When you are young, you interact with the landscape in a different way. We would venture out to get away from adults and interact closely with the land.

I see the mines as less of a scar on the landscape, but rather as a site that holds memories. The landscape is haunted by these histories, but that does not mean it is perpetually contaminated and assigned to the position of being a wasteland. Post-industrial landscapes are paradoxically places of abundance, resurgence and biodiversity. When you look below the surface, or see deers early in the morning crossing a wide stretch of land, you can see this clearly. As I encountered the landscape, I was thinking about Emma Marris’s insistence on the importance of recognising that nature cannot return to a pristine, pre-human state.

The area around the abandoned Michael Colliery, where I was working, is far from a perfectly preserved environment, but it’s an intriguing landscape. It’s not like a picturesque glen you might see on a calendar—those places, while visually appealing, often feel overly managed and lack depth or complexity to explore beneath the surface. This site, by contrast, offers layers of history and transformation that make it far more interesting to engage with.

When exhibiting at Summerhall and Hidden Door, I deliberately used industrial frames for my work to prompt viewers to reflect on the industrial origins of these landscapes. Often people walk through the landscape, entirely unaware of these histories, both environmentally and socially. I wanted to create an immersive space that fused the installation and space seamlessly. One of my biggest inspirations is Hans Haacke, whose work has organic pieces interwoven and layered across the exhibit. That’s how I wanted to display my work. His work transforms spaces; they act as interwoven systems rather than objects. I was able to experiment with these dimensions in different, more industrial and larger local venues.

Your series Darkroom Pedology creates an analogue between looking across the land in a more conventional landscape photo, and in looking at soil composition as a pictograph (a method employed by farmers to detect soil quality). Why do you think it’s important to offer the viewer these two perspectives of Fife?

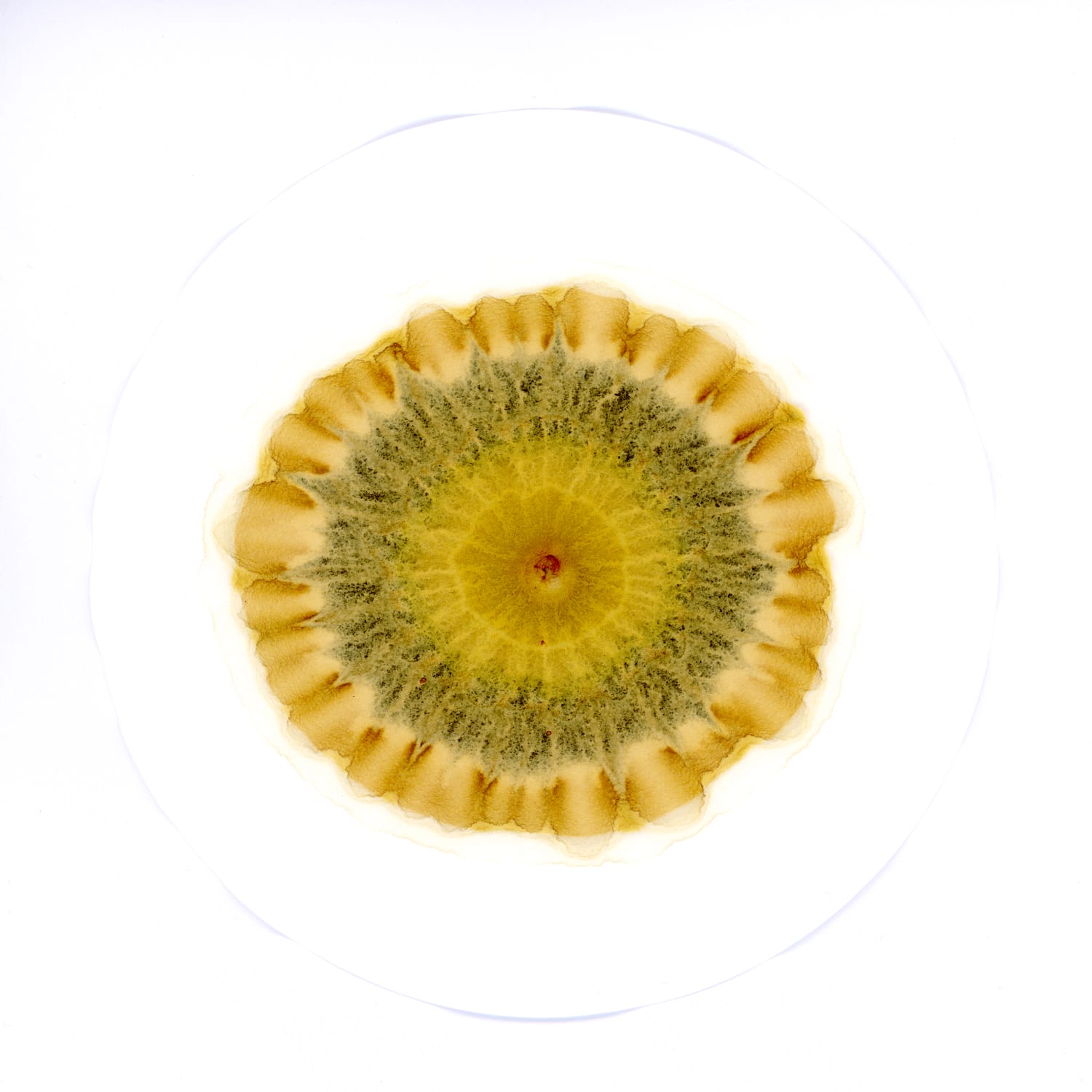

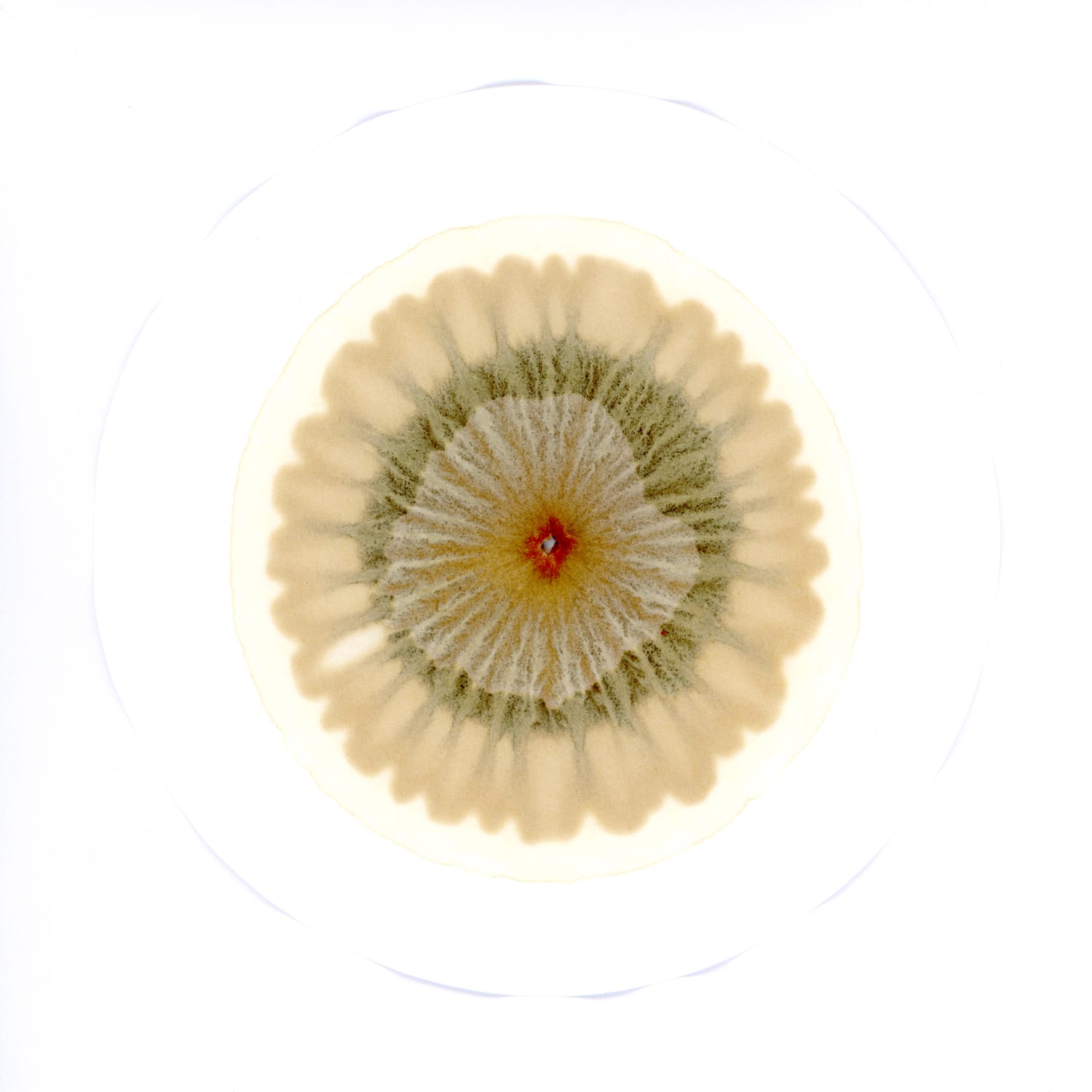

I was drawn to the idea of going beneath the surface, into the earth, given the context of working in a mining landscape. The project began with tracing maps to locate the old mining sites and tunnels. Initially, I photographed the soil alongside landscape images, but these felt unengaging and unlikely to resonate with people. Instead, I turned to soil chromatography, pairing the chromatograms with photographs of the landscapes they came from. This approach revealed a clear connection between the colors in the soil and the landscape above, creating a more compelling visual and conceptual link

However, I have stopped exhibiting them as diptychs. Naturally, when people see the Soil Chromatography, they already ask lots of questions, and I felt like it generated more conversation without having them immediately tethered to an explanatory landscape. I found that the chromatography itself produces the image and story of the place. They look best when they are back light, and displayed lower down so people look down to see them.

What does it mean to have eco-conscious artwork exhibited at the Saatchi and do you think it is indicative of the art world becoming more aware of how it contributes to climate inequalities?

It depends on how courageous curators and producers are willing to be. It is challenging for the art world, and commercial galleries in particular, to encourage sustainable forms which are less archival, and in general, unable to be sold and bought in the same way as their non-sustainable counterparts. That said, I think generationally speaking, artists themselves are becoming more engaged and willing to work in sustainable ways.

Exhibiting at the Saatchi Gallery was a transformative experience. Working and experimenting in the studio can often feel isolating, with limited opportunities for feedback—a sentiment I’m sure many of the other artists exhibiting shared. However, presenting work in a public setting breathes new life into it, turning it into part of a broader discourse, sparking conversations and interpretations you might never have anticipated.

I want my art to be as accessible as possible, communicating environmental issues to a wider audience. When people walk through post-industrial landscapes, they’re often unaware of the history and environmental legacies beneath their feet. By encouraging a shift from simply looking to truly observing, I aim to move this conversation beyond academic contexts. The problem is far too expansive and urgent.