Interview 074 • Dec 16th 2019

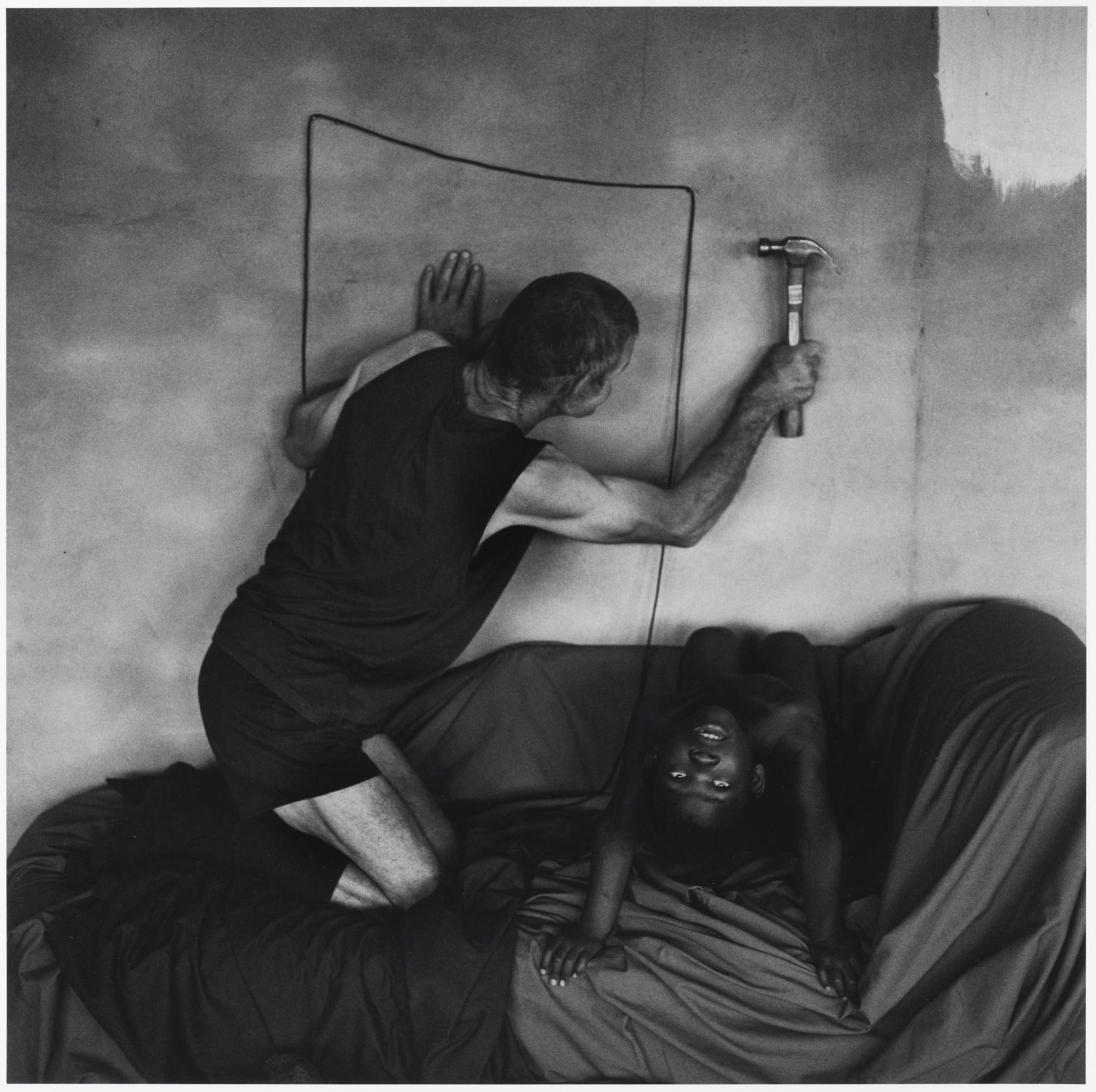

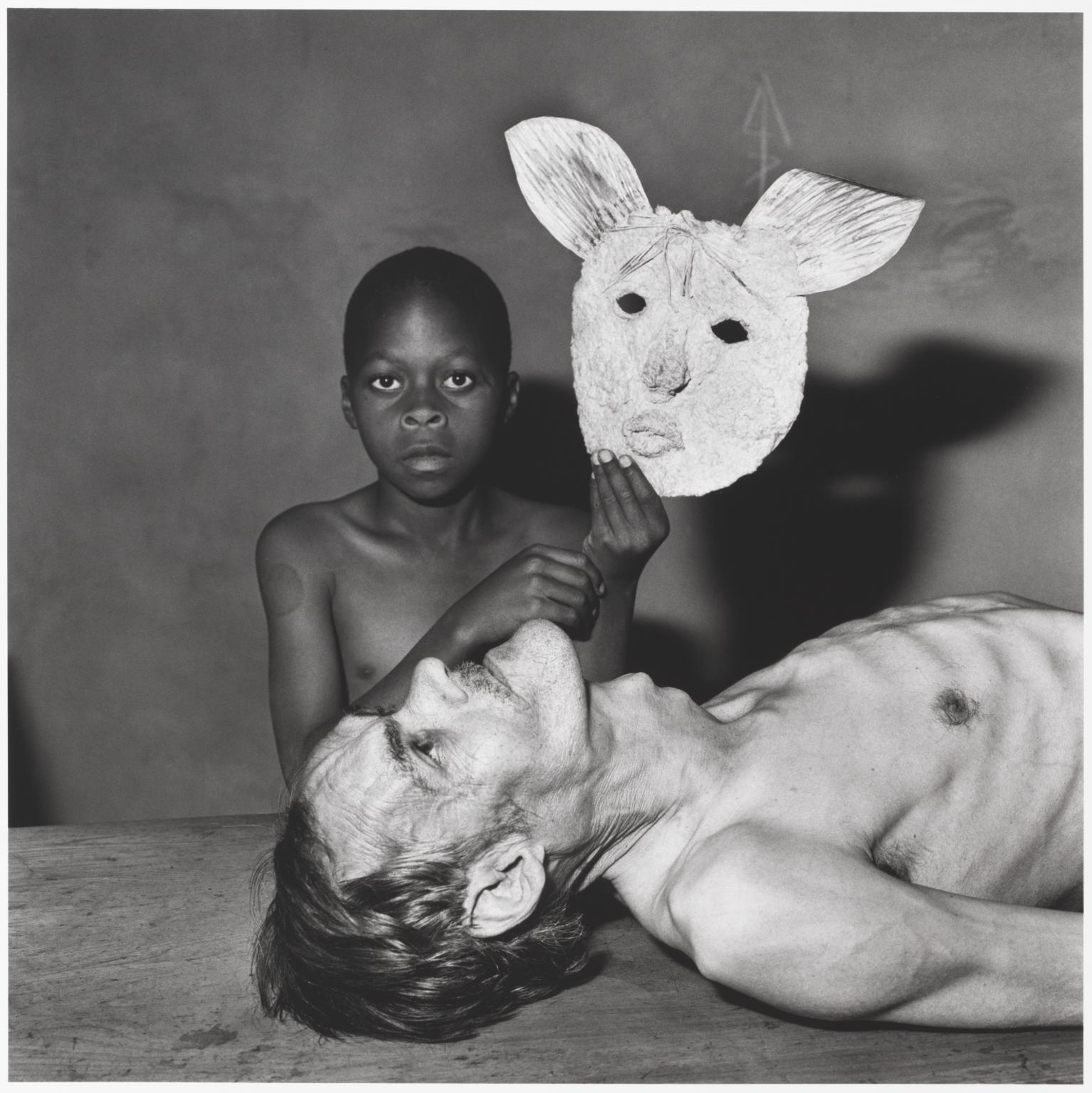

- Interview by Parker Day, Portraits of Roger Ballen by Chris Buck

About Roger Ballen

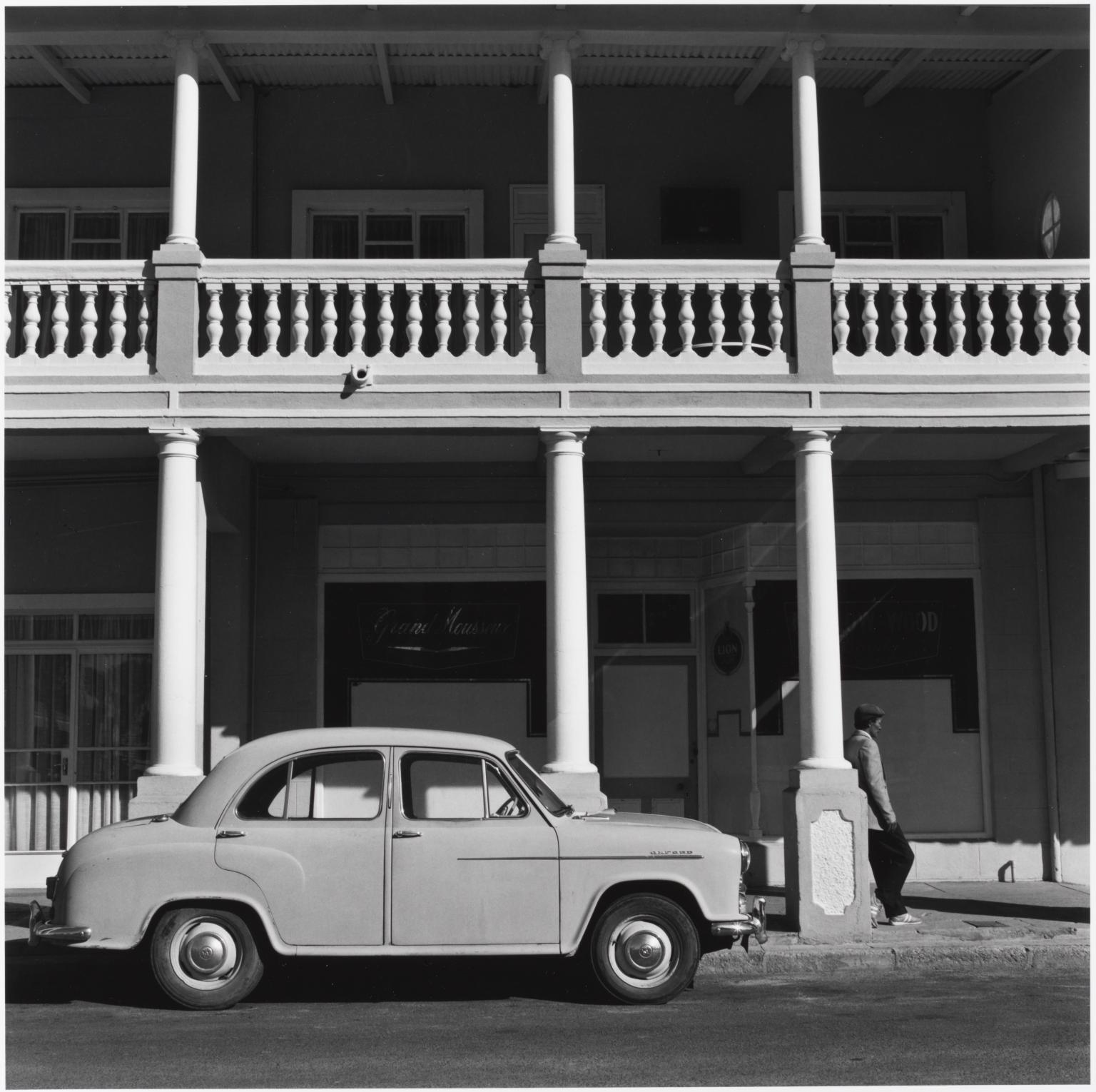

Roger Ballen was born in New York in 1950 but for over 30 years he has lived and worked in South Africa. His work as a geologist took him out into the countryside and led him to take up his camera and explore the hidden world of small South African towns. At first he explored the empty streets in the glare of the midday sun but, once he had made the step of knocking on people’s doors, he discovered a world inside these houses which was to have a profound effect on his work. These interiors with their distinctive collections of objects and the occupants within these closed worlds took his unique vision on a path from social critique to the creation of metaphors for the inner mind. After 1994 he no longer looked to the countryside for his subject matter finding it closer to home in Johannesburg.

Over the past thirty five years his distinctive style of photography has evolved using a simple square format in stark and beautiful black and white. In the earlier works in the exhibition his connection to the tradition of documentary photography is clear but through the 1990s he developed a style he describes as ‘documentary fiction’.

Links

Foreword

When we asked Parker Day who she'd like to interview, the name Roger Ballen erupted from her like a volcano. As much as we like doing our own interviews, reading this one, we definitely see how intriguing it can be to let two professionals get deep into it, discussing the psychology of their work, the constant negotiation with the world of social media, and the deeper issues involved in truly lasting work. Their conversation is exactly what we were hoping for, as fans of them both. Enjoy!

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

You studied psychology at Berkeley in the early seventies, it must have been an incredible time to be there. Psychology is probably the best training for being an artist. Never mind art school.

Yeah, it was an amazing time.

Psychology exists on a lot of levels, but for Berkeley and most universities, it’s empirically scientific; there’s really two sides to the field. It’s trying to prove theories that usually are quite absurd in some way, quite meaningless. “How a horse thinks when he turns his left ear.” You know, the more philosophical side more.

But with psychology, you’re better able to understand yourself, better able to understand other people. It trains you to go below the surface, which most artists aren’t doing right now.

Do you feel like you use your photography as a means to explore your own psychology?

It’s difficult to the come to terms with any of these concepts. I’m doing art for myself and always have. It’s a way of this expressing the complexity of who I am and my identity, in some way or another.

You do it but the mountain’s higher than you can see. And we’re never going to get to the top, so it is a process. As human beings we’re limited in so many ways, but true art is the best way of coming to terms with yourself. Very few other areas in human endeavor allow you to do this, to get to that point. But the Self is complicated.

It’s inexpressible verbally, so we can only begin to touch upon it through these images that work in abstract ways.

When you’re photographing, do you know when you’ve gotten the shot?

I never go to a place with any real idea. So I build the photograph piece by piece, and sometimes the pieces come together quickly, and sometimes it takes awhile. Sometimes you think you got it and you didn’t get it. In a way, if the picture looks too good it sometimes doesn’t work because it’s too logical.

There’s a important point, because you know up to about a year ago, I only used film.

And this is really true in film because I didn’t know what I took. It was difficult to walk out of the scene and say, “I got the picture,” but I have been using digital camera now for about a year and it’s a lot easier to see whether you got the thing, or came pretty close to it.

How do you think that’s changed your process of shooting? I like not knowing what I’ve gotten, while I’m in the moment.

It’s an interesting point, and I am walking around telling people now I’m a hypocrite. [Laughs.]

I’m liking the working with this camera, because I can know exactly what I’m doing. I see the mistakes before, so I’m more likely to get ahead rather than go back. So the mystique of the film is great, it’s it mysterious box and you’re not sure what’s in the box after you took the picture.

On the other hand, when you’re there you want to get the pictures. You want to do your best and materialize your efforts.

The digital does bring a lot of advantages, the quality that one gets on a digital cameras is amazing. Leica gave me one of their cameras. I just started to take color pictures. I’ve never taken color pictures my whole life and I started saying to myself, “Jesus, this is quite good, this is quite different.”

I’m getting into another zone and so this next project, which started about nine months ago, is a color series and it’s interesting to me that I had all these preconceptions but now I have to eat my words. So now I’m using pink color pictures and using a digital camera, and the transition has been very smooth. It’s been no hiccups, nothing.

Do you feel like that’s reinvigorated you?

Yeah, that’s what you want to be, when you get into a series you want to feel like you’re going into a zone you haven’t been there before and it’s worth exploring.

There’s a lot of young artists who are searching for a style and I think maybe searching outside of themselves. So do you have any advice for young photographers who are looking for their style?

You can’t just invent a style, because it just becomes contrived.

The problem is everybody’s trying to be an early success and come up with something that nobody else did before. It has to come naturally, it has to come over time, and it has to mostly come through a lot of hard work, a lot of concentration. Then you have to be inspired by what you do, but it’s it’s not something that happens immediately.

The issue of creating an identity in photography, it’s become so difficult. You look at the amount of pictures out there, versus maybe twenty years ago.

The whole thing is so flooded with this stuff, that to rise above it, there’s no formula. And if you’re actually looking for a formula you’re going the wrong way.

There’s no formula. I can’t become Picasso. I can’t become Michelangelo, I can’t become anything other than myself, but it took me fifty years of…you know, I’ve been doing this for fifty years, and my style only started to really become clear.

It’s a long, hard process and you have to be committed to it. My best advice that I can give any young photographer who wants to see themselves as a photographic artist rather than commercial photographers, you actually need another career!

HA! Say it ain’t so, Roger.

You have to find the right balance because to make money in the business, it’s very difficult. It’s really hard to sell pictures, and if you haven’t developed the style and a reputation it’s almost impossible. Yes, you can sell them at the Los Angeles park gala or something, or the Fireman’s Gala, somewhere in the middle of the city for a hundred dollars each, but I mean to get somewhere it takes years and years and you have to be able to do this with discipline over the long period of time and you have to be able to find a way of supporting yourself.

I appreciate that. It’s so true, and with Instagram now, there’s an opportunity for people who are coming out of left field to rise up and and get a platform. But yeah, it’s so flooded. It’s challenging to navigate.

There’s a hundred billion platforms. And the standard has gone to the dogs. How do you judge? How do you judge the image now? You’ve got to…on Instagram, going through the thing, there’s hardly anything really interesting. And then you look at the Kardashians or something. I don’t even know her first name, but she may take a picture of her red toenail and get two million hits.

It kills me, the fame game.

Was it a great image, or is it because…it’s obviously because she’s a celebrity. But the problem is the whole evaluation is now based on hits, it’s not based on any artistic merit.

It’s usually based on following, so what’s the image about anymore?

It’s true. I’d like to talk a bit about what you think makes a great image great, the science of it. What goes into some of your best work, for instance?

The great images are images that that exist over time and have impact over time and transform people’s consciousness.

They have a lasting effect on people’s consciousness. It’s the same for sculptures, painting. It’s something that has a relevance over time and remains, and has an impact on people’s subconscious mind and transforms their state of being in some unfathomable way. That, to me, is great art.

What’s happening in the market is…it’s been now pushed into this being contemporary and being relevant, but that’s what makes great art in today’s world. This is not something that I can accept.

Definitely, for a work of art to have resonance across the years, across the decades, it has to speak to something more universal.

You’re known for photographing people who would be termed outsiders. What is it about outsiders that draws you, do you feel like you’ve ever been an outsider?

Everybody’s an outsider. That’s the whole thing.

We have this crazy idea that we’re part of something, but ultimately the difficult things in life you have to face alone. Trying to face these things, there are no answers to most important questions. So we’re all outsiders, but people can’t deal with that idea.

The term Outsider is challenging because it does imply something of a socio-economic nature, insiders versus outsiders. I hope that we can find a term that describes a state of being that is more on the boundaries. We all touch upon quiet moments where there’s that liminal space between just regular functioning person of the world and transitioning over to something more metaphysical, that correlates to life-death crossover. That’s scary stuff. But that’s what we all contend with.

If you say outsiders, well what do you mean, who are the insiders?

Right!

Who are really the insiders? Do you really feel you know? You’re in harmony with yourself and every way so, and you have come to terms with all the things that made you feel on the edge. Well, that’s not possible.

Do you have any sort of spiritual practice that informs your art?

I’m Jewish by birth and I’m Jewish from an ethnic point of view. From the point of view of spirituality, the word I could use the most would be pantheistic. God is nature, nature’s the moon, nature’s an owl on a tree, and nature’s an elephant. Nature’s everything walking the planet.

I would have to say, definitely not an atheist, but I can’t come to terms with so many things that I actually don’t know what to think anymore. I have no ability to understand the word of God.

It’s such a difficult concept that I can’t come to any reckoning except that it’s mysterious, enigmatic, it’s beyond my capability. But I’m not divorced from it, I never call myself an atheist. Spirituality pervades everything I’m involved in, but I don’t know how to put my finger on it.

I love how in your work you incorporate animals and you’ve mentioned that animals a couple times in this interview. What do animals represent?

The animal in the picture represents the same sense of purity. She is in a state of alienation and breakdown. If you look at the animals in the picture, they’re in awful places, that’s the world right now for the animals. No doubt about that.

The nature of the world is not the situation of the dog in Beverly Hills.

Haha! I love that photo of yours with the cats clinging to the sofa. At one time or another we’ve all felt like that cat and maybe that cat is like the state of the world today.

The animal has all sort of metaphoric meanings to it, you can’t divorce yourself from the animal, we come from the animals.

This is no harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, it doesn’t exist. I travel, I’ve been enough places and enough things, it’s all illogical and illusionary to think anything else.

American people evolved in a state of being nervous with nature. Nature is seen as a threatening that something to cope with so it’s in our blood in them genes.

Something to be conquered.

In your work there’s a lot of your drawings, they remind me of cave painting, and of children’s drawings. The primitive early-man energy coming from it. What is that about for you?

This is something for somebody like yourself to figure out, because it’s a layer in the picture.

How does the painting and the drawing relate to the other things in the picture? What do the drawings reveal in relationship to the other aspects of the other of the other aesthetic aspects of the image? What are they telling you and where are they taking you?

You can’t really answer that question. I’ve asked a few people over the years. I said will be interesting if you can answer that question for me.

It’s part of my style, but the meaning of those pictures in relationship to the image itself, and how they transform the image and add to the image. You have to look at each picture in a way. It’s hard for me to generalize but it does add another layer of ambiguity of meaning and of aesthetic.

I can’t really answer the question. It’s part of what I do and if I took out the drawings would the pictures have the same meaning?

These are important issues to deal with in photography. They’re difficult challenges. But to me, that’s the profound place to go. It’s not about going on the street and taking another picture of another civil rights march, or somebody getting beaten over the head by a policeman, all the stuff that doesn’t lead you. I would did that forty, fifty years ago, just the same stuff over and over again.

You want to get deeper and inside of things. If you’re I don’t know that’s what I want to do. I don’t care speak about it with other people but I think a lot of what we see in photography business, is not breaking the surface. I tell most people these days are so, “I wanted the exhibition.” I’d rather go on the sleep tonight because I could have seen what I saw on Time Magazine the other day.

H! Don’t pull any punches Roger, I like it. It’s so true that people are scared.

I don’t care about I’m just that’s where I’m at. I live in a different environment here in South Africa than in America. It’s different and it’s not just it’s, so maybe that’s why I ended up this way.