Interview 071 • Oct 15th 2018

- Interview and Portraits of Rick McGinnis by Chris Buck

About Rick McGinnis

Rick McGinnis is a Toronto photographer and writer who has been working professionally for over 30 years. Although his photography has appeared in The New Yorker, Spin, Esquire and the Village Voice his mainstay clients have always been local publications like Metro, NOW and Nerve, which has provide the majority of his portrait assignments.

He recently published three fanzine format books of his photography.

Links

Foreword

Four years ago Toronto photographer Rick McGinnis began a modest blog called Some Old Pictures I Took, that turned into an epic exploration into his value, his failings and his purpose. This included posting hundreds of portraits from his thirty year career - many of them great works. The blog took on an autobiographical tone as McGinnis discovered shoots and wrote about the circumstances of his encounters with Hollywood A-listers, musical royalty and other cultural icons.

With Rick having decided to bring the blog to an end, I thought it a great time for a conversation about his career. Rick and I started together in the mid-eighties at a monthly music paper in Toronto called Nerve (for whom he also wrote). We were competitors and friends, making our long connection both complex and powerful. We sat down to talk in his backyard in central Toronto.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

What’s the best lesson your father taught you?

I didn’t know my adopted dad for very long, he died when I was four. My sole memories are waiting for him to come home from work, and watching Looney Toons with him in the living room. Everyone who spoke about him after he was gone said he was a very quiet man, but very smart. He didn’t say much, but what he did say was intelligent and worth listening to and generally good counsel. I’ve always regarded that as something to aspire to in my life (though I am a wholly verbose person who speaks way too much).

What are the choices you’ve made that have made you who you are? Give me three overt choices that have brought you to where you are today.

Dropping out of college. That was basically me saying, “Okay, that’s it, I’m done with being in the waiting room of my life.”

What were you studying?

I was studying English and Theatre at the University of Toronto. I just decided, “No, I’m not going to study anything anymore, I’m just going to go out and make mistakes.” I’d been getting a couple bylines published, and I figured, okay it’s not that hard obviously, I can go out and I can be a writer.

A second thing…staying in Toronto. I’m not going to say that that was a good or a bad decision, it was a decision I made and it definitely changed my life. I may have ended up in roughly the same place, in the long run, but in the short run, I think things would have been very different. I know this city better than any other place in the world. I know too many of its faults and shortcomings, and I know how frustrating it is to do anything here.

Staying was a pivotal decision for me. A lot of things did not happen that might have happened if I had moved to New York, but then again they’re “mights.” I don’t know what they would have been. I know what happened when I stayed here, and for good or for bad it’s kind of led me to where I am right now.

Third decision, getting married and having a family, which are two things that I never really thought I would do, or do well if I did. I desperately wanted not to be a single man but that eluded me for years, I was a really shitty bachelor. And as for being a parent, I was terrified of it because I have no real parenting role models to speak of, so I thought I’d be pretty bad at it. I really didn’t think I was dad material.

When I actually did it, I was basically forced to do it by my wife (chuckles) I turned out to be not such a very bad idea at all – in fact it’s been a great idea. But I would have not thought so at the time.

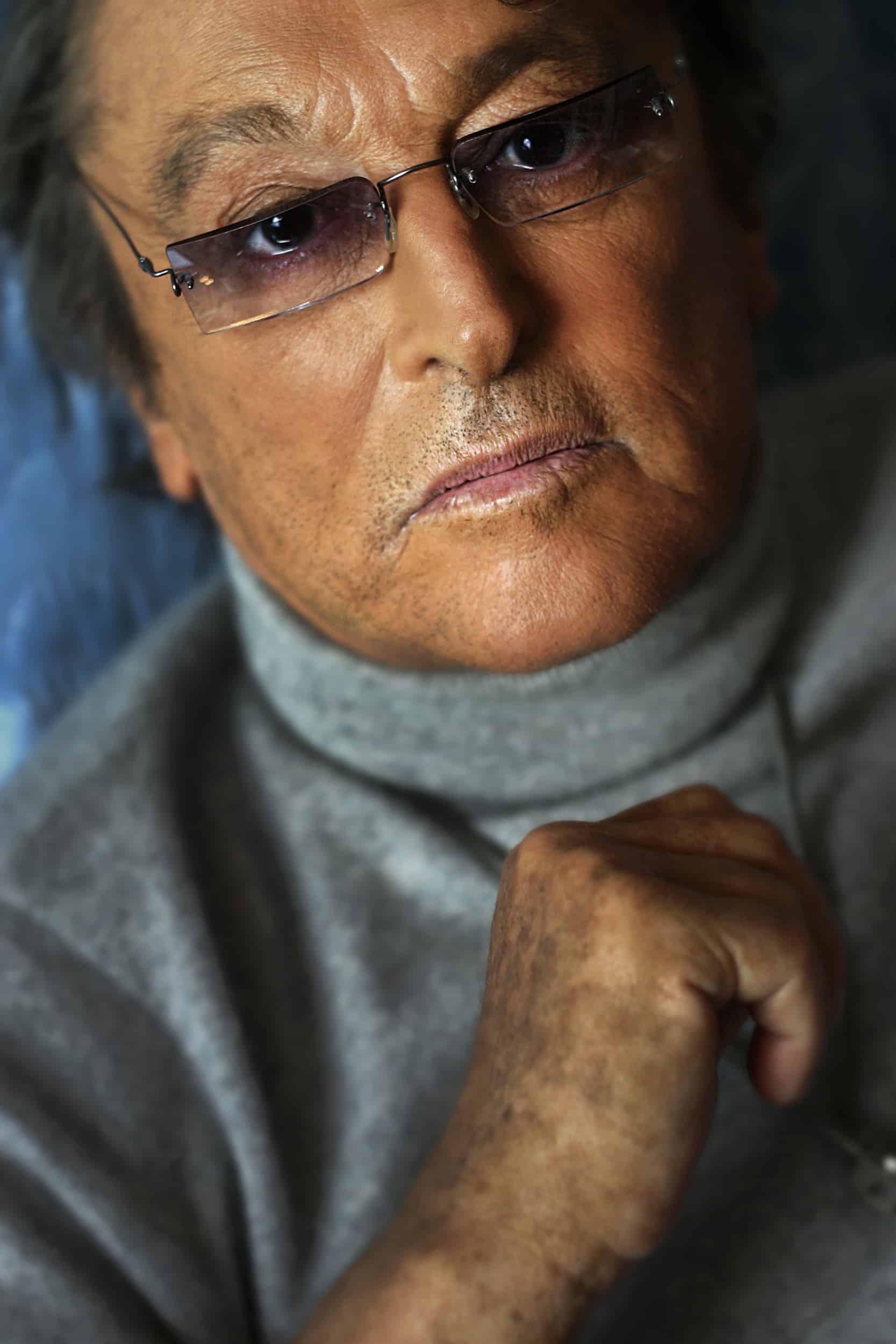

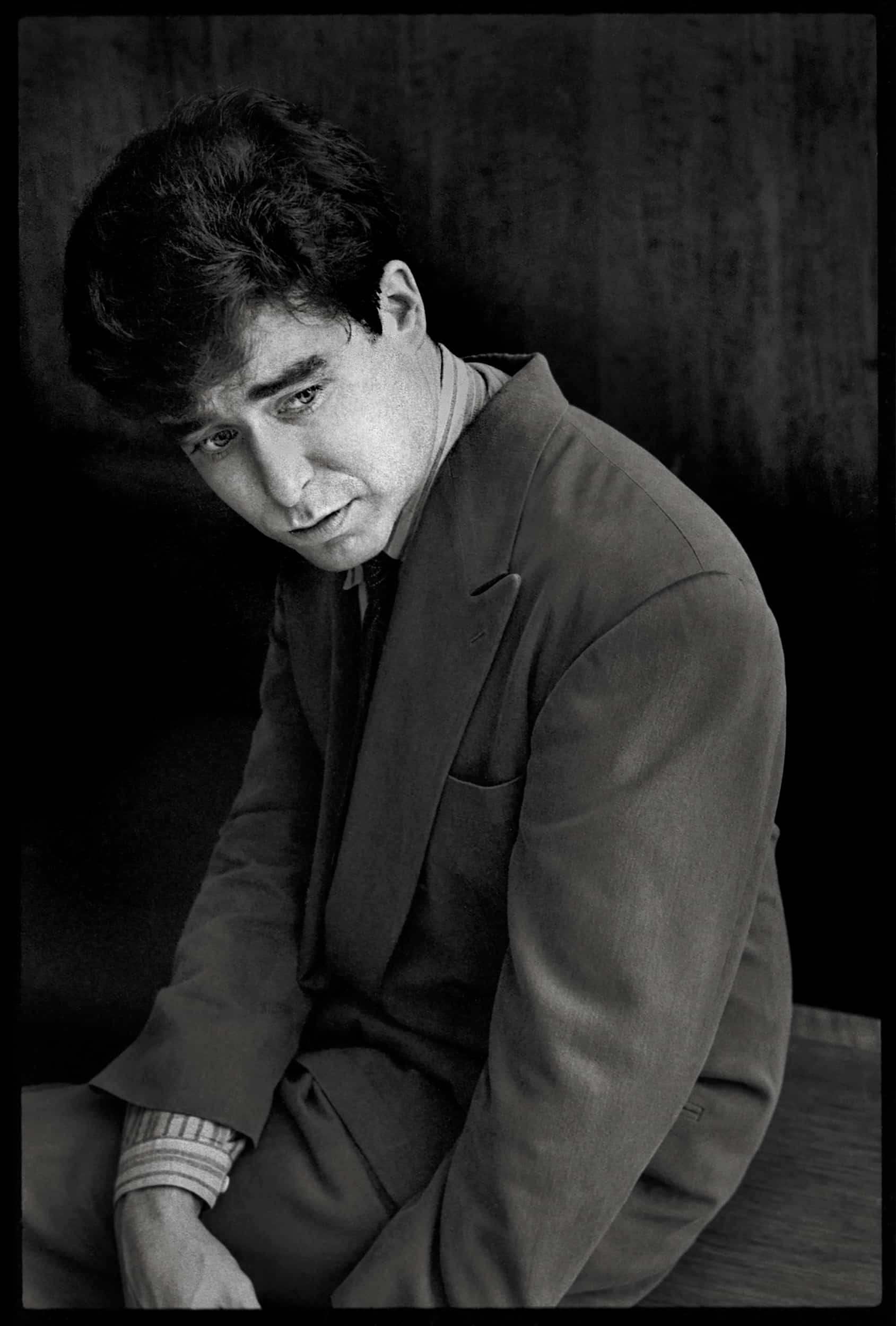

right: Gary Busey, 2004 left: Robert Evans, 2004

Let’s talk about fatherhood. The sense I get, from my own experience, and also looking at friends like you, is that if you have some basic standards and you make some kind of effort with your kids, you’ll be a great dad.

Hmm, who is it who said that? Is it Gavin McInnes or somebody?

Some genius like that.

Ha!

I haven’t spent a ton of time with you and the girls, but the amount that I have suggests to me that you are a great dad. That there’s a level of appropriate authority but also gentleness and respect they have for you that you also have for them. To me, it seems lovely. I’m going to ask you not to argue with this, what do you think makes you a great dad?

I treat them like people. I treat them like separate human beings with their own tastes and proclivities and oddnesses, and I love that about them. They’re both such terribly different little creatures. Well, not so little, they’re almost 6 feet tall the two of them. They’re kind of fascinating that way, you look and think, “Where the fuck did that come from,” and, “Why are you doing that?” And, “Wow it would have never occurred to me to do that.” It’s an unduplicatable experience, it doesn’t happen in any other thing that you do in your life.

How do you think your being Catholic and a believer, in the traditional sense of being a regular churchgoer; how does that play into your photography?

It’s two things. One is the cultural Catholic thing. The other day on Facebook I posted, 10 Books in 10 Days. And the last book I put up was our family Bible. It was an early fifties pre-Vatican II, American Catholic Bible with two or three sections of old masters, Biblical paintings and scenes. El Greco, Fra Angelico, that kind of stuff. That was the only art book we had in the house the whole time I was a kid.

Tilda Swinton, 1992

Did you grow up in the Middle Ages?

No, I grew up in a working class Catholic neighborhood (chuckles) there weren’t a lot of books.

I would pour over those pages endlessly, looking specifically at these El Grecos, which I just found sublime. There was something about those figures and the way, they were obviously people but there was something, there was like a flame inside them, some kind of incandescent glow that I found fascinating. I thought, “Wow, how do you see that?” Obviously the world doesn’t really look like this but it’s so convincing that he’s managed to convey these people like this. Also, Caravaggio’s paintings was just amazing, and I couldn’t even identify it as a quality of light, it was just, “How come these don’t look like everything else here?”

The second, if you’re a misanthropic person like me, when you’re forced to be part of something, to go to mass every week, to take part in this communal ritual, and everything else it entails socially, it kind of forces you out of that negative mindset and makes you think about people and their souls. You just can’t help it, that’s obviously the subject at hand.

Does that concern you as a photographer?

Absolutely.

But you’re a professional soul-stealer.

And maybe that’s the appeal. My whole job is to go in and open the control panel and see if I can’t find the soul. I really like that moment when I sit down with somebody, whether they’re a celebrity or not. And that’s the thing, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to care less and less whether I’m dealing with celebrities or not. And just getting in that weird zone where it’s just you and the subject and there’s as few distractions as possible. They know what you’ve got to do, and you know what you’ve got to do, and there’s that standoff that happens for a few seconds where you’re looking at each other and thinking, “Okay, what are you willing to give and what am I going to get out of this.”

Sarah Polley, 1997

One of the things that I thought would be really great for this audience is for you to give advice on to how someone working in those situations can get better at it or just good at it. It’s those, between one and fifteen minute shoots, in a controlled space, whether it be a boring office or conference room, a hotel room.

Well first, just technically you’ve got to get rid of everything (chuckles) – it’s just a distraction.

Do you see other people who were lighting, and therefore, missing opportunities that you had?

Yes. I would see these guys from The Toronto Star or The Globe & Mail show up with little lighting kits. What they were doing was trying to perfect the light in the hotel room. I understand that they often were doing this because they were shooting color slide, (technically very demanding), but so much of their time was spent dickering around with gear.

While the subject was there?

Yeah! What I would do, during the interview, is just watch them and figure out how they moved their face. Just staring at them from a corner of the room, looking to establish some sort of familiarity with them. Whereas these guys weren’t doing that, they were dickering around with crap. And I just thought “No,” and I started leaving all my lights and stands, everything at home. By the early nineties I’d striped everything down to two Rolleiflexes, a tripod, and a Sekonic light meter.

Also, go fast. My thing is always just get their attention quickly, lock eyes, even just for 10 seconds before you take a shot, just look at somebody, and just look at them hard. And lately, I actually will do a little spiel with, especially actors, I’ll say something like, “I need something happening in your eyes.” Remember this is a super close up, this is a tight frame.

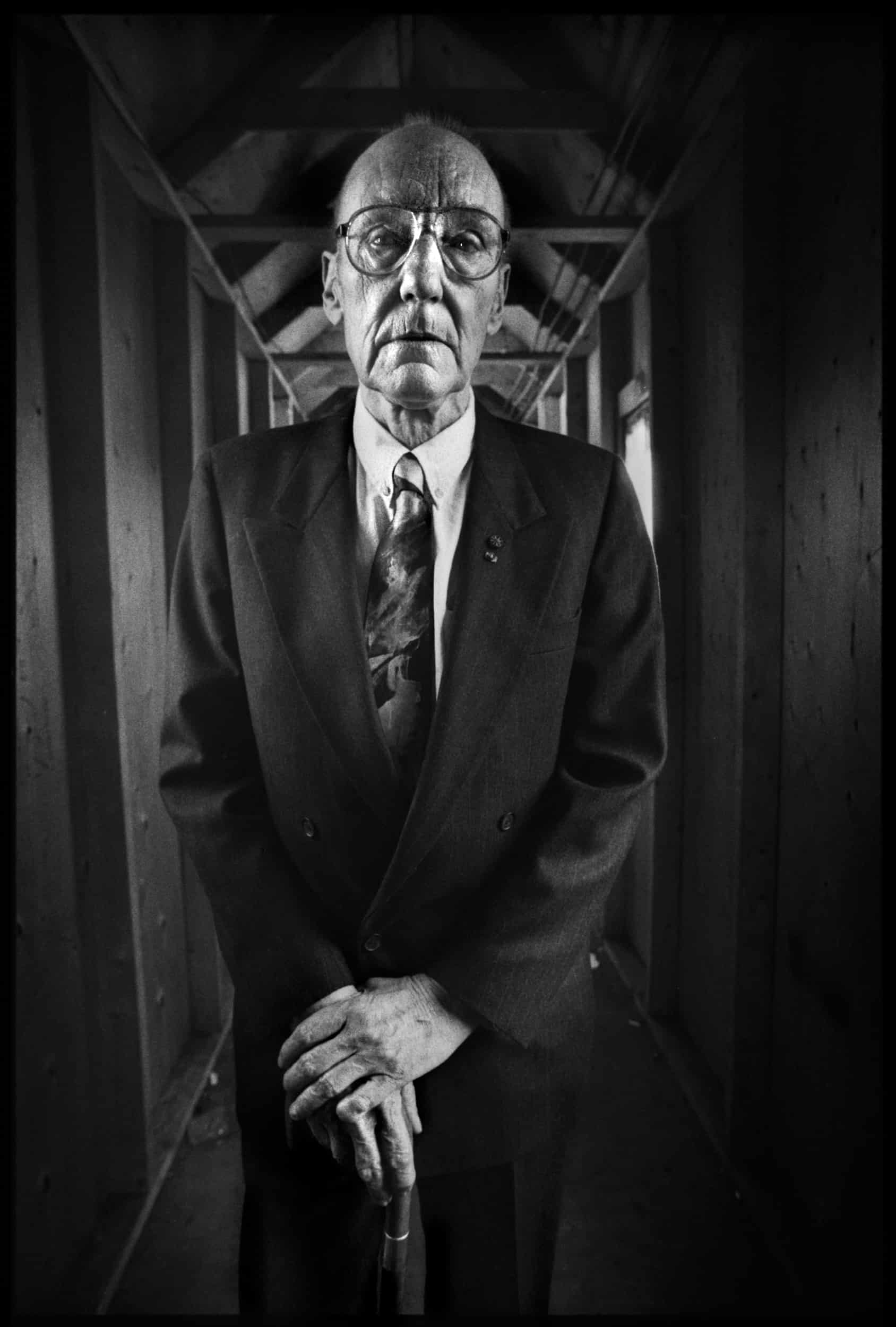

right: William S. Burroughs, 1991 left: Gene Simmons, 2004

And they don’t say, “I don’t want you being that tight?”

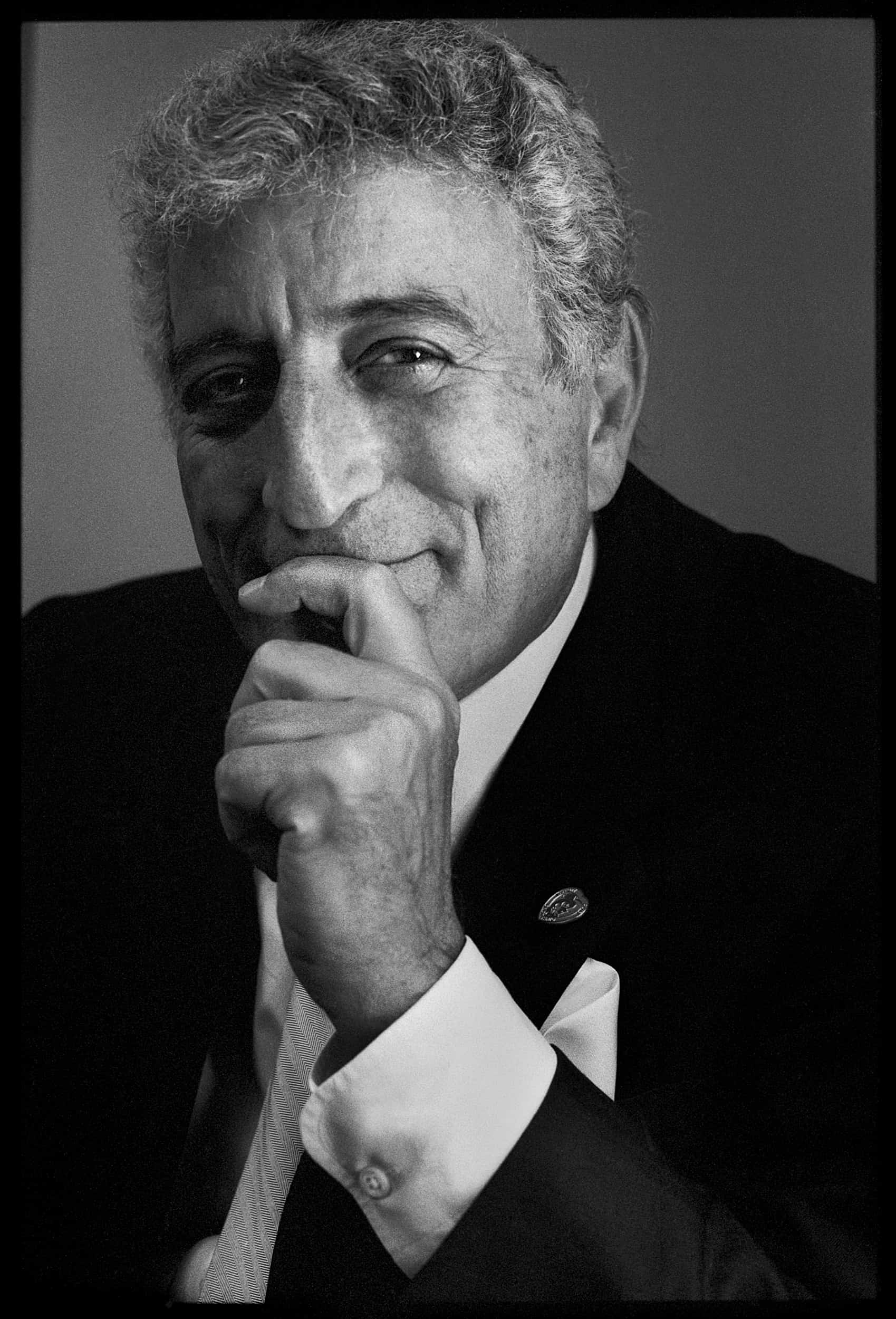

Not usually…well, sometimes they will. The second last person who said that to me was Tony Bennett. And with him, I was really close, I was in there tight with a 50mm filling his face.

That’s a great shot. One of the things I love about your tight pictures is that, you’re using a normal lens on those. It ends up giving a slight distortion, it’s quite nice.

Yeah, 50 to 35mm.

It really gives that sense of a you being in the room with them.

With Bennett, I was almost in his lap. He said, through his teeth, “You’re getting really close!” I said, “Yes, I am!”

I’m leading a workshop in this fall, as I prepare for it I realize, it’s not about lighting, or whatever, it’s about like being okay with subjects being a little weirded out about you.

Look, Tony isn’t going to be my friend.

Tony Bennett, 1993

Whether you say it, or you just, your body language says, “I’m here, deal with it.” There’s something about it that most people, and especially successful people will respect.

He’s doing his job.

You’re going bold. I want to go back to an earlier topic. The first time we met, you came to me and said, “I’m Rick McGinnis, I’m moving to New York.” So what was the origin of this big scheme to move to New York?

The kind of photography that I loved, by and large wasn’t being done in London, or any other place, it was being done in New York. Irving Penn was in New York, Avedon was still shooting in New York. If I wanted to be serious, if I wanted to be published in the magazines that I wanted to be published in, I needed to be in New York. So, I always kind of had this plan, and it remained on my mind probably up until the mid-nineties. At one point I sort of took stock of my situation, my life and my state of mind and realized I couldn’t do it.

Why?

I was not mentally able to do it.

Was this something that had always existed and you just suddenly realized it?

Perhaps, it took me a while to understand it. The thing I didn’t really know until years later, I was terribly depressed.

For most of the nineties I was very unhappy. I had a bad breakup in a relationship that basically put me on the back foot. I’m not a risk taker by nature, I can’t see myself just selling everything, picking up, reducing my life to a few boxes, and relocating to a city where I know almost nobody. As much as I fantasized about it, and thought maybe I could do that, when I saw you do it, and I saw what you needed to do to do it, I thought, “Oh fuck, I’m not sure if I can do this.”

But you had nothing to lose.

Yeah, technically. But I felt like I had very little, and I had that much to lose. There was at least a certain amount of stability that I could count on having my family nearby, most of my friends, a city that I was familiar with, where I knew where the dangers were, where the dangers weren’t. I thought, “I’ve got that much, I’ve got this much that I’ve managed to accrue in life,” I could lose that, and it terrified me.

You have to understand also my personal situation: I’m adopted, my adopted father died when I was four. That puts you in a situation where you’re prone to fears of rejection and that sort of weird, anonymous, random feeling like, “There’s no reason for me to even be here, another roll of the dice and I wouldn’t exist.” Everything seems very arbitrary, so what little you end up accruing in life, you can call your own. It was suddenly very precious. You’re loath to even risk that because you can see, if you lost that, what the fuck would I have left, really.

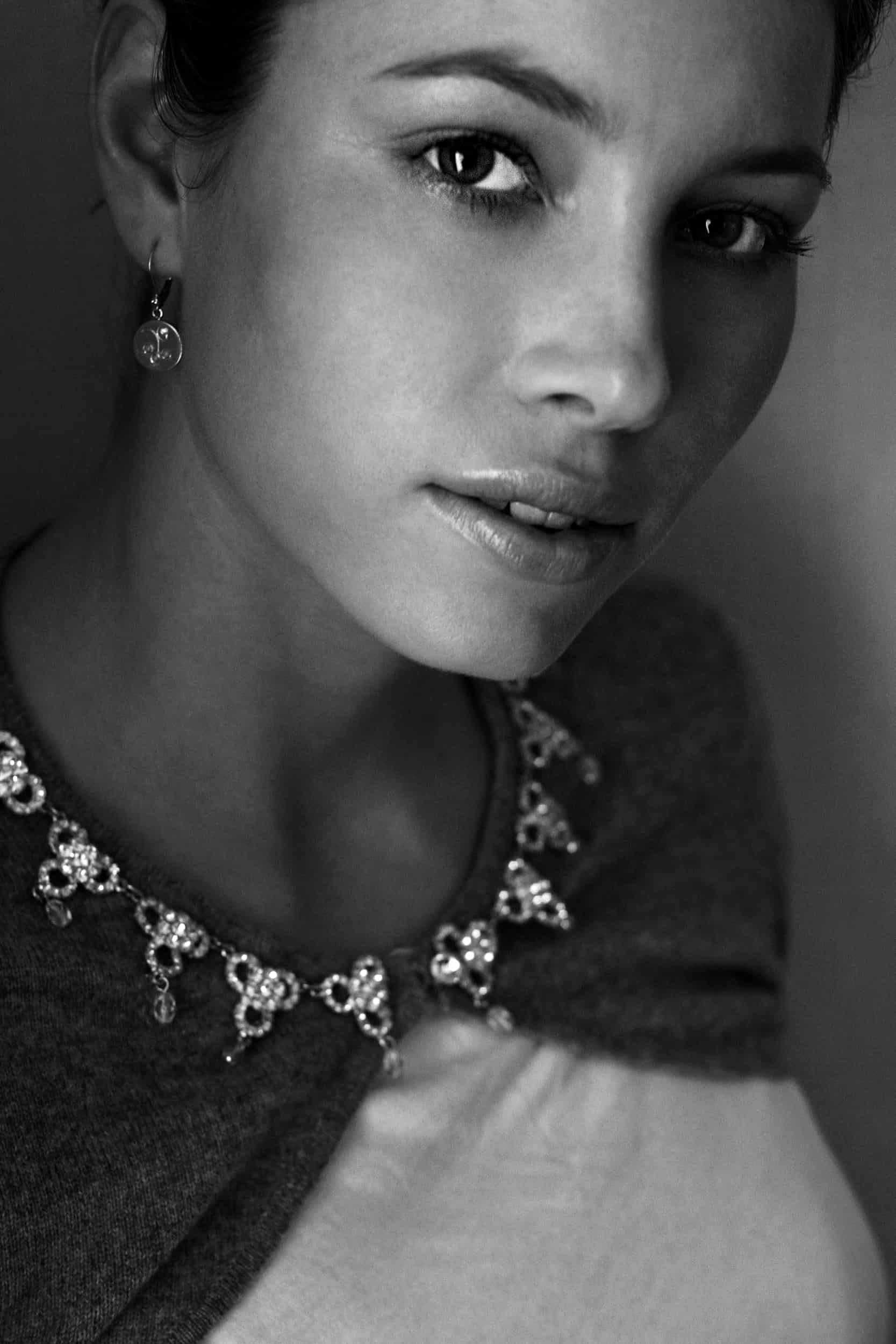

left: Jessica Biel, 2004 right: Jay McInerney, 1988

Let me flip it then, how has that served you well?

You can just look at the time traveler’s conundrum: if I had left, I would not have my wife I would not have my kids. I would not have this lovely little backyard in my modest little house in the West End of Toronto. This is the first actual sense of emotional stability I’ve ever achieved in my life, and that’s not a small thing.

The shrieking demons, or whatever you want to call them, they’ve always kind of been there for me, and I’ve always been frightened as to fuck about losing control, or something going wrong – being pushed too far and having nobody and nothing to help me. I’m not in that situation anymore, and that’s because I did stay here, and I did sort of tough it out to the point where I did meet this woman, she did convince me that we should start a family, I am now at this point where I’ve got 30-some years behind me where I can sort of analyze what I’ve done.

What do you think she sees in you?

Oh God, you’d have to ask her, I haven’t a fucking clue…I’m funny. I don’t know. I’m not a bad cook.

You can be very generous. I remember when I moved to New York, you threw me a little party, and I didn’t even realize we were that close. I remember you turned down a shoot with Don Rickles in Las Vegas to host this little event. And, I will tell you, I would not have done the same thing.

I know, haha!

It speaks to who we are as people. And I mean, I don’t think I’m a bad person, but I’m very driven and I think I make my choices.

Which is one of the things that I know about you and one of the things, as your friend, I am comfortable with.

I’ve never really had much of what you call a support structure in my life. So the few people I’ve met that I felt I was sort of sympathetic with, whose tastes I understood or whose outlooks I could understand, actually became kind of precious to me. I’m not emotionally demonstrative or anything, I’m just not.

Maybe it didn’t seem obvious to you, but you were one of the few people I could actually talk to about things. Specifically, there’s this business we were trying to understand and this art that we…

I know I feel close to you and very connected. Partially because of our history, but also the way in which our trajectories have kind of reconnected through our interest in politics and religion, and being married and having kids. But also, I think maybe we both matured in ways that made us more relaxed with ourselves, therefore, more civil to each other?

Yes.

But at the time, I remember very distinctly feeling like you talked to me in a way that was condescending.

Oh yeah, I did that with everybody. It was my coping mechanism. I grew up the smartest kid in my elementary school. I got beaten up constantly because I did that with people, I talked down to them almost nonstop, haha!

So, yes, we’ve got shared history, it’s a big deal. It’s over 30 years for the two of us. It’s a big bond to have with people, and you feel a sense of sympathy, and even a gentleness with them.

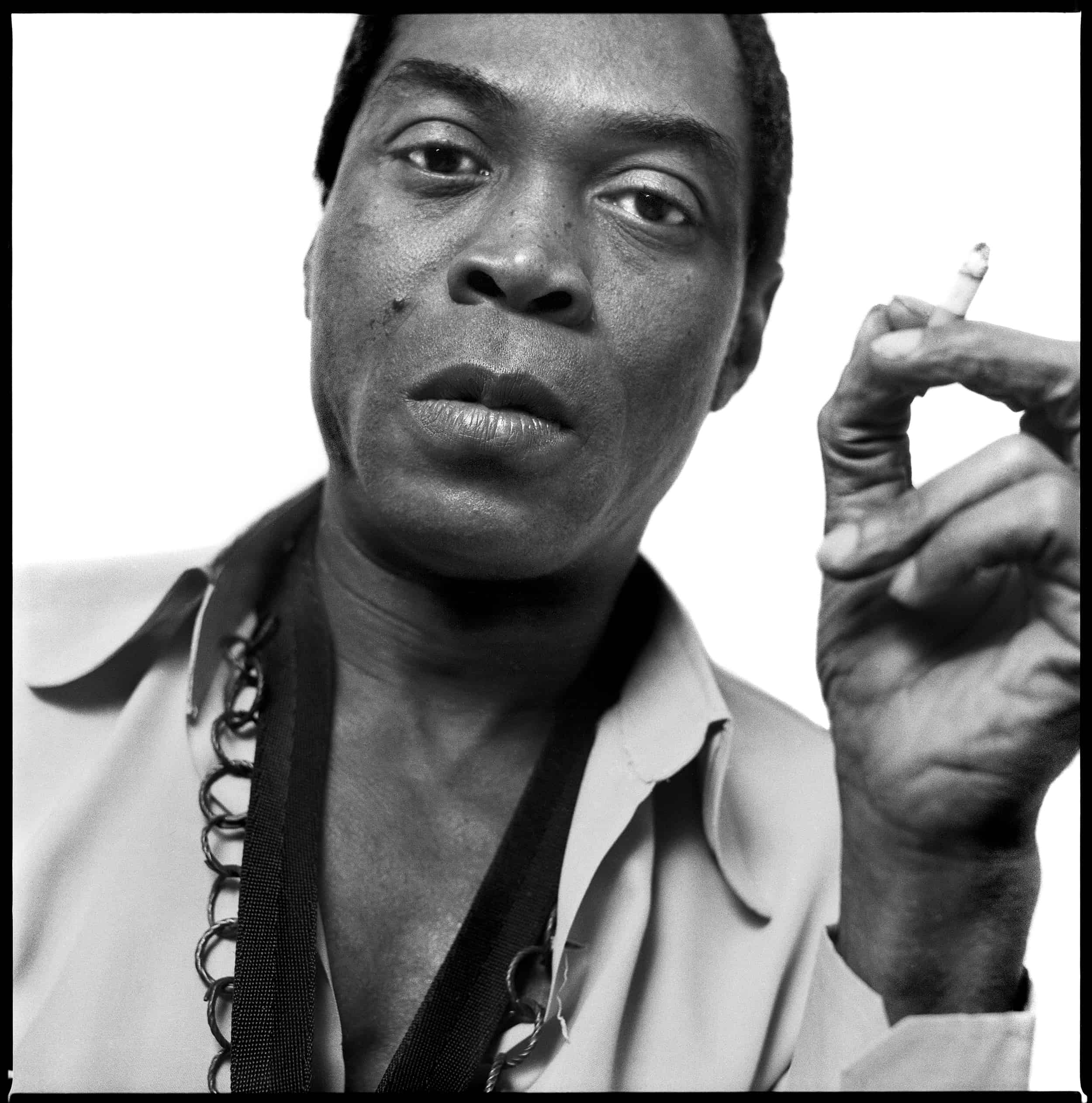

Fela Kuti, 1989

I feel similarly. I really appreciate you staying with it and I’m sure there are times where I was either distant or even, not particularly friendly, and you were patient through it and stuck with it and stayed open. At some point we reconnected and I was ready to go there, and I really appreciate it. And our friendship matters a lot to me, too.

You’re one of the reasons why I actually bothered going back to this. Years ago, when I was working as the photo editor at the free daily. You came into town we went out for lunch. I wasn’t really shooting anything. I was sitting there all day, eight and a half hours a day. Nobody was hiring me to do anything, in my mind I’d come to the conclusion that perhaps maybe that was a period of my life that was over. I thought, “I was a photographer for a while and now I’m not anymore.” You turned to me at one point and said, “Start shooting. Would you just start shooting again.”

(Whispering into the recorder) He’s doing the hands prayer position.

And I was touched by that, like, “Wow, somebody actually gives a shit enough about what I ever did that they think I should maybe keep doing it. There was no great clamor to see me shoot another photo in this town, so I felt kind of grateful.

If it makes you feel better, that crippling silence of lack of interest, it’s sort of normal. I think that’s how most people feel. So tell me about the blog. Give me the basic outline, and the origin story.

The blog is called Some Old Pictures I Took. I was sitting around, four years ago, feeling sorry for myself. I had been sending out resumes, for three or four months, trying to get another newsroom job. My wife walked into my office one day and said, “Do you get it? You’re not getting another newsroom job, it’s not going to happen. There’s no more jobs and if there are, they’re going to give them to someone young who they can pay much less who can be much more malleable than a miserable old guy like you are.” I said, “You’re completely right.”

Did she phrase it like that?

Pretty much. Well, she’s learned that’s how you have to speak to me, ha! She said, “What is it you want to do right now with your life? You’re approaching late middle age, you must have some sense of mission, some purpose. Put some effort into the last…she didn’t say this, but I interpreted it as this, your last great surge of effort into crusting Act 3. “So, go think about what you want to do.” So I came back about a week later and I said, “You know what, I think it’s the photos. In a way that writing doesn’t give me, not even close.”

Vince Vaughn, 1998

Yay we won!

She pointed to the shelf in the corner of my office, “You haven’t looked at your old negatives in years, why don’t you just start going through them and seeing if anything’s worthwhile.” Go set up one of those free blogs and just post it, see what happens.”

I pulled a box down of 5×7” proof prints and started scanning and putting stuff up online randomly. There was no logic to it at all for the first year, I was just seeing if any of it was any good. Some of it, the stuff I remembered really well, the Nureyev shoot was a very big deal for me, and I could put that up pretty early. William S. Burroughs, David Lynch, you know, things that I remembered as big highlights early in my career.

I put those up, and I really started to get into it, and I thought, “I’m going to have to go back to the beginning, to Nerve Magazine and start going through all of that stuff, and then the NOW Magazine period, and then, with a sense of dread, then I have to deal with the stuff at the free daily, which because they laid me off, I don’t have a very fond memory of.”

I put stuff up, and I liked some of the things that I saw, but also realized that even if I don’t like it, I want to talk about how this failed, or why this didn’t meet up to my expectations.

And “failure” was the word that was on my mind the whole time because even as I started doing it, it was a record of failure, for me. It was about my failure to ultimately make a living, to make a reputation for myself, to make the big splash I had wanted to make. And I thought, “Well, you can grouse about that, or you can actually try to understand what you did right, what you did wrong, what your successes were, what are your failures.”

Now that you’re near the end of the blog, the finishing point is more nuanced than that, isn’t it? It’s not binary, it’s not failure and success; it’s more of a mixed bag, right? Because there’s clearly a lot of great work in there too.

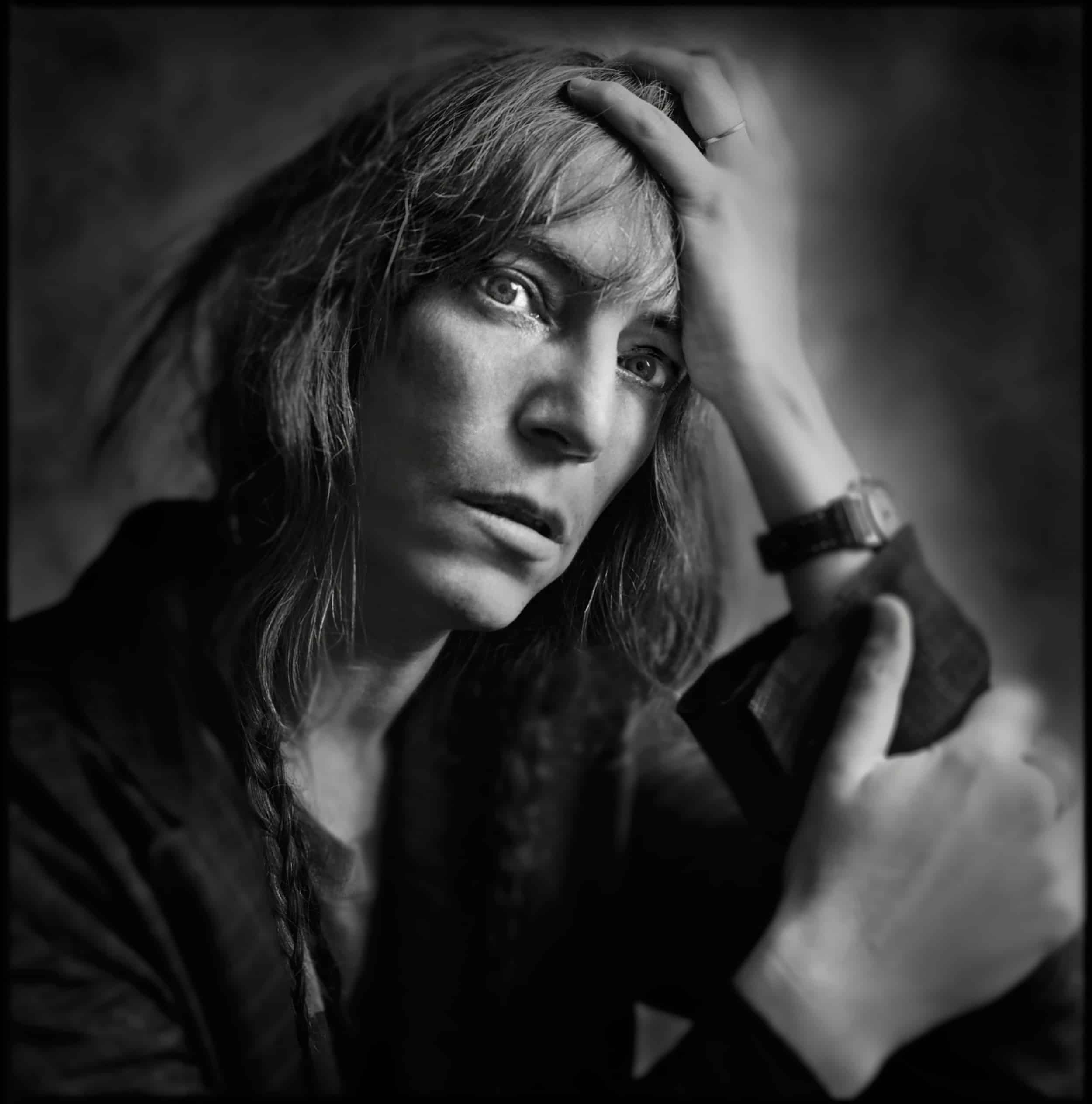

Yes. I remember when I thought something was pretty good. When I walked away from a shoot thinking, “Okay, I think there’s something there.” And then I remember shoots where, like Patti Smith, I couldn’t produce a good print from the session at the time. There was something technically that I wasn’t able to pull off and I did that shoot in the mid-nineties.

So that’s been good, it’s almost like a reinventing, having a second pass at these points, at being able to improve the work that I did back then.

Patti Smith, 1992