Interview 083 • Oct 22nd 2023

- Interview by Agustin Sanchez,

- Portraits of Kyle McDougall by Dan Rubin

About Kyle McDougall

Kyle McDougall is a photographer, filmmaker, YouTuber, and podcaster— to simplify things, a creative. Kyle started out in television and film working as a cinematographer while traveling the world filming action sports, worked as a traditional landscape photographer, ran his own video production company creating commercial and documentary content, sold everything in 2017, and road-tripped across North America for a year.

Since then, he has been all-in as a film photographer, making the work he's most passionate about and creating content online that helps others excel with their craft.

Links

Foreword

Having the audacity to change careers, even adjacent careers, is something I've always admired.

Kyle had a successful career as a founder of an established video and film-making studio. But as he reached "success," he found his idealized goal didn't fulfill him creatively. So, he took action.

Refocused on photography, Kyle built a photography community around him, fostered a celebrated YouTube channel, and most recently published his own photo book.

Success is a very personal metric. Kyle's YouTube channel fuels his creative projects, while giving back to the film community through education and documentation of his process. Set free from client work, Kyle thrives in his creative process on his own terms.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

You started off in videography, making films. How did you make the jump to focusing on photography?

Photography is something that I always have done alongside video. Photography was always a side thing that I would dabble with from a business standpoint.

It was my escape from the day job of video and filmmaking. I did that for quite a long time, until about 3 or 4 years ago.

When something you love doing becomes your job, it changes its dynamic. It wasn’t until I moved from Canada to the United Kingdom in 2020 that it was kind of a reset for me. That’s when I decided to get out of commercial video production and pursue photography full-time. But a large portion of that for me is also YouTube. So both worlds still blend together.

How do you distinguish between YouTube and your photography? One obviously feeds into the other. Are you conscious of the audience?

That’s one of the biggest challenges, to be honest. When I went into YouTube, I never started it thinking “I’m going to grow a YouTube channel and do this full time – and be a Youtuber,” or whatever people call them. It was at a time when I was getting back into film.

YouTube was a way for me to express my creative side, but also share what I was learning – allowing me to document the questions that I had and the things I was curious about. It kind of grew from that. It’s important to stay true to yourself and share your experience, but at the same time, you have to be giving people value. It can’t just be “Come, watch me shoot photos.”

Every video I make is framed from the perspective of, “What can I teach? What could I share with you?” I think there is this blend of sharing your journey, but also being very intentional about making sure you’re creating material that has a purpose, and that can teach people something. From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

One thing I’ve appreciated, and I think it stems probably from your background as a filmmaker, is each one of your videos is very focused. Whether it’s a gear review, a process, or a piece of equipment’s use… there’s always a story the audience can learn from.

It’s funny, I’ve been working on a video today exploring a different concept where it’s a POV that spends time with a new medium format camera – a day at the coast. I’ve seen videos with 5 to 7 minutes of ambient sound while they’re shooting. As I’m starting to edit this new video, I’m already struggling with the fact there are gaps in me not saying or teaching anything.

It’s cool to hear you say that. It’s something that I certainly want to keep moving forward with, but I’m also trying to switch things up a little bit here and there.

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

One related conversation is about that shift in how a photographer markets themselves compared to just a few years ago. Some might argue that you’re judged on how well you build a following online online, versus being judged on your work. Do you think that that is to the benefit of the dismay of most photographers?

I think it’s scaled exponentially because of the tools that are available nowadays, but I don’t think it’s necessarily all that different than the mindset from 15 years ago. I think the bones of it are the same, but the landscape was so much different at that point in terms of how you would promote yourself how you would network.

The possibilities and choices are endless, to the point that it complicates things incredibly. The challenge as I’ve transitioned to going full-time and building my business around social media is learning how to operate within that world in a way that is sustainable – creatively, and mentally. It is easy to be “on” or feel like you need to be “on” all the time. That feeling can influence the decisions you make from a creative standpoint.

15 years ago, when I was doing landscape photography on the side, I was doing art shows, I was making up flyers, I was mailing things out… The goal was, and still is, “How can I get my name out there? How can I get my work out there?”

It’s just a very different approach now.

Perfectly said. The hustle has changed, but it’s also the same old hustle. Was there a watershed moment for you that made you move from your filmmaking day job to photography?

I wouldn’t say there was one moment. For me, the transition out of filmmaking and video production was something that I saw coming over a year or two years of just lacking fulfillment. The goal of video production was to work for bigger brands and bigger companies. If I could work for X Company that’ll feel like “I’m succeeding,” or “I’m making it.”

As I got older, I just didn’t really care about that anymore. The size of the company or the size of the gigs was no longer the appeal. When I was moving to England, I left my video production business in Canada. It left me at “What do I want to do next?” And then Covid shut things down.

All of these things came together. And that’s when I decided “Maybe I’ll kinda give this a go…”

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

Most of your portfolio documents the United Kingdom and the States. Do you feel that as a landscape and environmental portrait photographer, you do your best when exploring a new place?

Absolutely.

We all become very used to our surroundings. They become normal and then can start to not inspire us after some time. All the trips I was making to the American West were really exciting for me. I explored new areas there and then came to the United Kingdom. A lot of my time here is spent just driving and checking a new places. There’s always excitement there.

I went back to Canada last year for the first time in about 2 years. I was in my local area I had tried to shoot many times before. But all of a sudden it was just like I was seeing all of this stuff everywhere. I was viewing it in such a different way.

Coming back to England afterward, I was digging through my old negatives and re-scanning old work that I didn’t like in the past. Now I was really excited about it. I think when you detach from a place that’s really common, you view it differently afterward. We get used to the places that are around us and maybe we don’t see them in that in the same way that someone else would.

That’s a really common struggle, to find beauty in the things that we see every day. If you came to Miami, where I’m at, you would find gems that I might never see.

It’s it’s funny how that works. I see it when people photograph in areas that I’ve been to before. Even when I was moving over here, I had a lot of people messaging me saying, “Oh, why are you leaving Canada to come to England?” Is it just a grass is greener type of situation? Since I’ve been here, this place has been incredible and endless in terms of where you can go.

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

Have you been able to make connections with other photographers or filmmakers in the United Kingdom?

Quite a bit. Life has been really busy since I moved here with a new business, 2 young kids, a house, and all the elements of transitioning to life here.

I have been connecting with other photographers online and meeting up with people here and there. Free time for me is a struggle.

When I’m shooting always prefer just to work by myself. That’s kind of when my best work is made. Especially when I’m shooting photos and filming YouTube episodes… my process is so chaotic. It just wouldn’t work with anyone else around.

How do you balance your home life versus work, especially as you’re working for yourself? Do you set any boundaries or employ any task management methodologies?

I try to work just pretty standard hours like a Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 type thing. I try to stay pretty regimented with things but also take advantage of the flexibility that I have as well. I’ve always been good with being self-employed and managing certain deadlines and stuff. I know if I don’t do what I need to do, this isn’t really going to work.

How do you handle creative blocks by working by yourself?

That’s probably one of the biggest challenges, especially as I’ve transitioned into doing my photography full-time. Video production work was a little different because you had a client. There was a specific brief. The ebb and flow are just a reality of any creative career.

In the past, I was really stubborn. I would get frustrated if something wasn’t working and I wouldn’t accept that. Maybe I just needed to detach and do something completely different. That’s what I’ll try and do now. I might look at stepping away from image-making for even a month, and just focus on teaching. Some things that maybe aren’t as exciting to me that are still valuable.

I think acceptance has been the biggest thing to take note of. Don’t force it and take a break.

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

It’s interesting because photography was that step away that gave perspective when you were professionally doing video production.

Exactly.

So as you transitioned to photography being your main job, there are opportunities for other things to be that sort of step-away moment.

A hundred percent. That’s the challenge right now. Figuring out what that is.

But to be honest, having 2 young kids now I would say, a big part of what that looks like now is like spending a day with my family. It’s like a complete detachment.

I try to keep in mind that regardless of burnout, or feeling it or not feeling it, one of the realities of being creative is that we just, go through constant periods of resistance, where we’re telling ourselves we’re too tired, or we don’t have any ideas, or we don’t have anything to say…

I’m always conscious of if I am actually burnt out, or if am I just having a ton of self-doubt. Is it something I just need to push through, or do I need to step away? It’s a balance. Trying to be clear on which state you’re in is important because otherwise you can just get stuck in the wrong place.

Sometimes, it’s just you getting in the way of yourself.

Yes.

I was actually thinking about this the other day. I wonder if anyone has the answer to how to distinguish the two. One of the biggest things that holds people back from doing the work they want to do or pursue with their art is that resistance of “Am I not good enough, or am I too tired?”

Early in my career I would face that situation naively, thinking “Oh, well, you know, 5 years from now, once I have this all figured out, it’s just gonna be great being in the groove all the time.” I’ve learned now, after doing this kind of work professionally for a long time, that there’s just a constant struggle. It ebbs and flows some weeks of feeling it – some weeks, you aren’t.

You find the biggest growth when you buckle down and keep doing the work… even when you don’t feel like it.

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

Staying present in the moment to keep perspective can be difficult. There’s a whole discipline within the creative process of coming back to sift you through images to curate bodies of work. You start to see a whole other side of the work you’ve created.

I’ve accepted that detaching from my work, and not making any decisions too quickly, is beneficial. I almost always end up viewing it differently with some separation.

I have not been happy with most of the work I created here in England for the first two of the three years I’ve been in England.

At this point, I’m getting into a groove. I see it differently. I’m enjoying it.

A lot of that has to do with understanding different cultures. It’s just now that I’m starting to understand traditions and certain things that stand out to me as very British. And that influences how I look at the work.

Giving yourself time is so important, especially nowadays. That’s something that can be difficult for people. It’s easy to feel like you constantly need to be producing and putting work out… shooting and sharing. It doesn’t give you to just let your work sit for a little bit, and not have it become something right away.

Are you looking for something in particular? As you’re selecting those images as you go back into your catalog and sit for a bit do you find there’s a through line with what is attracting you?

There’s nothing specific that I could say other than intuition. I think that guides so much of my decision-making. When you know, you know. Recently I just wrapped up my first book. I worked with the publisher that was going through all of the work that I created in the American West.

When we did the selection we talked through all the work and we both picked our favorites. Then the publisher went and did the first sequencing of the book, essentially picking from the large pool of images that we had both said, for the most part, we liked.

It was really interesting. There were images that he had selected, that I would have never picked if it were me doing it by myself. But seeing them in there, seeing how they were sequenced… the images just took on such a different life.

It made me realize that my way of choosing through my intuition isn’t necessarily the only way. It was proof that there were images I had created that maybe I’m missing. Or maybe I’m not kind of giving credit to.

I personally tend to thrive in collaboration, so I fully recognize the benefits of multiple perspectives being generative together. The sum can be bigger than the sum of its parts.

For me, it’s being indecisive and having these other traits that aren’t always the best for moving projects along. It certainly helped to have someone who’s like, “Okay, I’ll put together the first thing, and then I can kind of look at it from there.” No doubt it’s better than it would have been if I tried to do it by myself. I think that’s a really, really valuable thing for artists to be able to partner up with someone else.

From 'An American Mile', photography by Kyle McDougall

How did An American Mile come about? How did you link up with your publisher?

To be honest it just kinda happened naturally. I was pretty fortunate that I got connected with Subjectively Objective through Instagram. They do a series called “monthly monograph.” It’s a small zine of an artist’s work, with maybe 10 to 12 images.

They’d approached me in the past to do one of those. Then I submitted work for a couple of their collaboration books that collect work from different photographers into a bigger compilation.

Then I actually reached out to interview Noah, who runs Subjectively Objective, for my podcast. We kind of just got to know each other from that.

He enjoyed my work, we chatted about publishing, and then it kind of went from there. I was pretty fortunate to connect with a publisher whose work I really enjoy right off the bat. I know it’s obviously not an easy thing most of the time.

An American Mile chronicles your work in the American Southwest. What’s the period that you were taking those images?

It started in 2017. The last trip was in late 2020. It was about 4 years of making work that essentially started with me and my wife on a year-long road trip.

We sold our house and bought a truck and trailer with no plan. From there, once it started to grow I went back on numerous trips.

I’m assuming most of An American Mile was shot on film?

I would say, like, 90% of it is on film. There are maybe 5 or 6 images that were digital on it.

Did you have to re-edit or rescan anything to drive consistency?

The work was created over such a long time. The first year I was traveling I sent film out to lots of different labs. There were inconsistencies with different scanners and resolutions. We ended up rescaning almost all of it with one workflow. We wanted to have everything as high quality as possible.

It just limits variants in your pool of images for your project.

Exactly. I might have a 2,500-pixel wide image from like 2017 and a 10,000-pixel image that I scanned at home beside it. The goal was to get the images through one process with consistency, which was a task that I certainly don’t recommend. Get it right the first time, basically.

What do you hope that people take away from An American Mile?

That’s an interesting question. To be honest, the work on An American Mile was never intended to have that kind of goal. I’m trying to say something very obvious. It started out very innocent and intuitive.

Being immersed in these landscapes felt really special to me. The first 6 months were purely creating images with a bit of genuine curiosity, an innocence that you have when you first start photography. You’re not in your head yet. You’re purely just going out and making work without thinking about if it’s good, or if it’s anyone’s gonna like it.

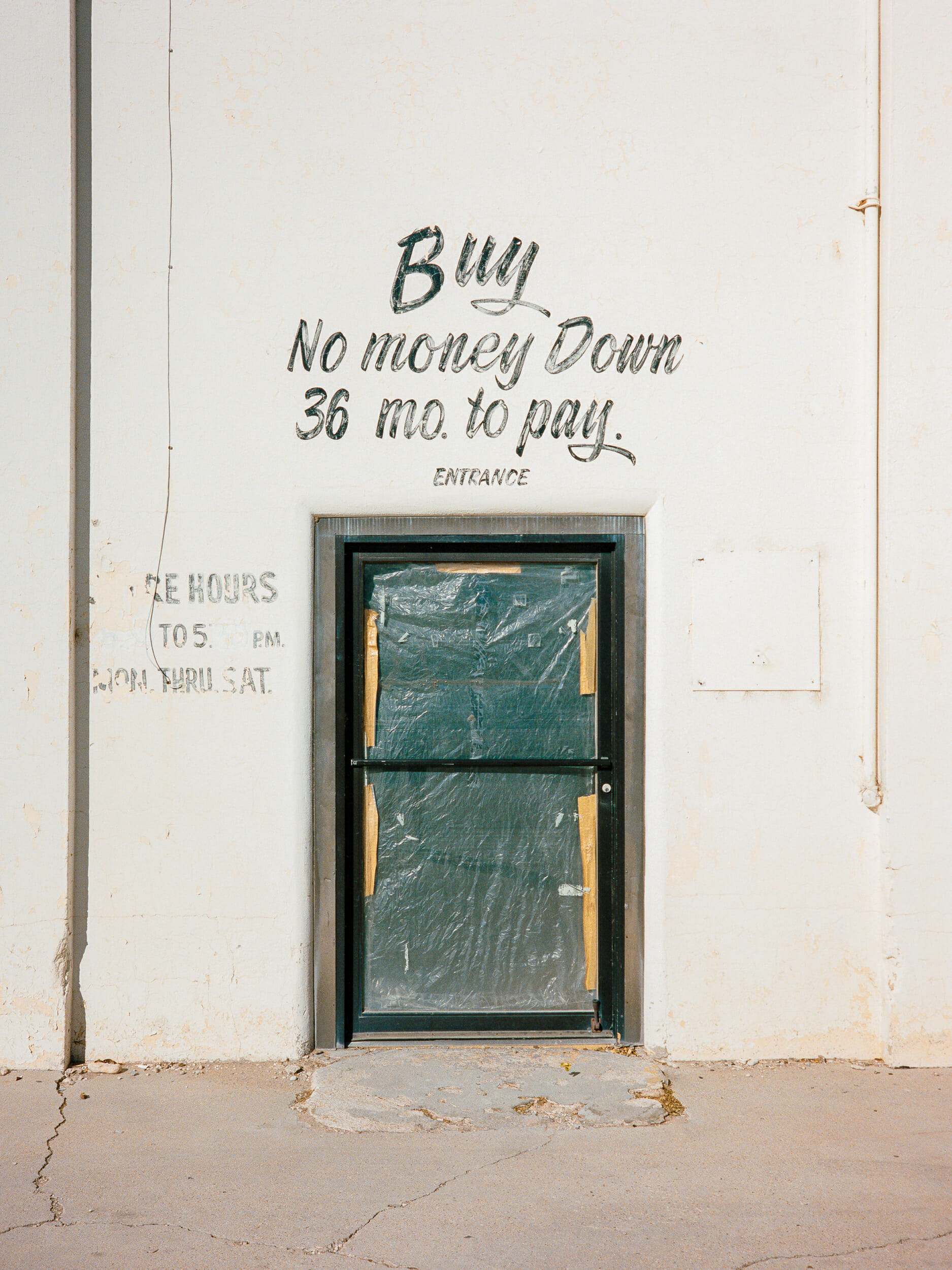

From there it just evolved. Obviously, it is documentation of the American South in these in-between places. I think the attraction for me, with all of the subjects and the places I went, is a desolate wide-open feel. That was the draw from me with my older work. Just being by myself in the wilderness.

Then the theme emerged. These places are run down or closed now, but all these towns and main streets were a completely different story just 20 to 30 years ago. That was something that I thought a lot about. It’s hard to be in those places and not think about time. It wasn’t that long ago that these places were completely different. The shop you’re photographing was someone’s small business that they just started. It’s just a reminder of how quickly things things change.

From 'Slate City', photography by Kyle McDougall

I really resonate with the idea of just creating and not worrying. I feel like the early work I did, the work where I was exploring, is my favorite. I wasn’t in my head yet. I was creating out of passion and curiosity.

Now, I’m almost always trying to get back to that. I’m always trying to get back to being in the moment, purely moving through intuition to create something special that’s not necessarily planned.

It’s interesting to hear you say that because I think that happens to a lot of us.

Obviously, it’s good to try and bring structure and thoughtful consideration to your work and your approach. But I certainly have learned that it can really get in the way to the point where you’re not even making anything. You’re just sitting at home trying to figure out all the details, and it’s not until you go to start shooting that you with really no intention can sometimes discover completely different directions. That’s certainly what happened with this work in the American West for me.

I think one of the most important things people can do is to get clear on what matters to them. If you want to get into photography, and what you really enjoy the most is just geeking out about like old film cameras, and that’s all you want to do for the rest of your life – then that is what you should do.

You shouldn’t force yourself into a box if you think you need to go and try a have an exhibition, make a book, or whatever. But at the same time, if you’re trying to make it, have an exhibition, or make a book, or whatever it is, and all you’re doing is buying film cameras and testing them out, you should probably stop doing that and pick one and get on with making.

From Slate City, Kyle McDougall

Speaking of creating new work, how many concurrent projects do you have going right now?

I would say the easy answer is one. I’m focused on work up in North Wales. The working title is Slate City. It’s basically focusing on this town that was considered the slate capital of the world. Its landscape has essentially been shaped by the slate workings from 100 years ago. It’s just super fascinating. It took a little bit to figure out, but once I started doing some work, and came up with the title it really came together.

That is the only project I would say that’s locked. I have ideas bouncing through my head all the time. Some are probably really bad, and some are probably really good. But I don’t end up doing them because I can’t decide if they’re good or not.

While one project is locked in, I do have this ever-growing set of folders in my Lightroom catalog, where I’m making a folder for an idea that comes up. As I make work that might fit into a project I’ll kind of put photos into that folder to revisit later.

I really appreciate your time to talk with us! This was a great chat. Cheers.

Thanks, Agustin!

From 'Slate City', photography by Kyle McDougall

⁂

Dan Rubin’s portraits of Kyle McDougall were developed and scanned by our partners at Bayeux, the photographic place in London’s West End.