Interview 063 • Mar 30th 2018

- Interview and Portraits of Killii Yuyan by Lou Noble

About Kiliii Yuyan

Kiliii Yuyan is an indigenous Nanai photographer and journalist whose award-winning work has been published by The Nature Conservancy, Pacific Standard, Der Spiegel, National Geographic Traveler China, and been exhibited around the world. On assignment, he has fled collapsing sea ice, weathered botulism from fermented whale blood, and found kinship at the edges of the world. He is based in Seattle.

Links

Foreword

It takes a lot of strength and courage to endure some of the world's harshest conditions to tell the stories of the Natives who call it home. Kiliii finds ways to tell his own story and examine the roots of his heritage through incredibly poignant portraiture and documentary work, a stark difference from his humble beginnings as a designer-slash-commercial photographer. Finding the hopefulness in any circumstance, Kiliii's laughter is infectious, and his desire to share stories untold is obvious as he contributes to Native cultural revitalization through his work.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

So one of the first things that I wanted to ask was, what got you into photographing the communities that you’ve been documenting for the past few years?

You know, it’s a bit of a long story.

Long is good for us, yep, that’s our thing.

I started as a commercial photographer. As a commercial photographer, I was shooting for REI, and photo assisting on adventure shoots, all kinds of stuff like that.

And what got you into that?

Into commercial?

Yeah, and photography in general. I’ve seen in other interviews where you talk about the work you’ve done, but how did you get started in photography?

I was trained to be an industrial designer, and then I got into graphic design because it was a way for me to make money as a freelancer. Over time, I dabbled in photography because the clients I had were often non-profits, and didn’t have the budget to hire a real photographer.

Gift of the Red Salmon

Mmhm.

So I ended up doing the photography, and it turned out to be better than design. And some of those first attempts were so awful!

Sure.

As a young designer, I was thinking to myself, “I need these shots, it should be no big deal to shoot them.”

Yeah, piece of cake.

This was at the very beginning of digital cameras, the terrible 3 megapixel cameras, you know. But over many years, I started to take the camera out on wilderness expeditions I was doing at the time, and I would take pictures on occasion when I was out there. I found that it really useful to be able to tell the story of what I was doing. Slowly, I made the decision to become a professional photographer. But, you know, my career trajectory as a photographer changed a lot.

After being in the commercial industry for a while, I got sick of being an assistant. You’re at the bottom of the totem pole. I didn’t stay an assistant for that long, and when I began shooting as photographer, there were great times and I worked with some great teams. Even so, at the end of the day, I felt a kind of a hole, an emptiness, from doing the kind of work where I was just selling. Ultimately I felt the work was just selling gear to rich white people.

Haha! I understand.

At this point I was speaking to a career consultant who was helpful to me. I’ve found consultants to be incredibly helpful, because they just see you in a way that you can’t see yourself. My life is pretty unusual, but in truth my life is all I know. I don’t find it unusual, but I do find other people unusual, ha!

Ha!

So my consultant helped me understand more about photography, and life in general.

What kind of consultant did you go to?

There are consultants who help you do editing, or your website, but I found the most useful was helping to guide my career. When I was at a critical juncture after being disillusioned by commercial photography, she said, “Your stuff is technically well done, but it lacks soul. I’ve seen all this before. You are such an interesting person, you need to dive into your unique background and explore who you are.”

The last thing I wanted was to open the can of worms of my indigenous heritage. For someone like me, a Chinese-American who’s also indigenous, it’s really tough. In China, being indigenous 10 years ago, 20 years ago, was not a good thing. In China you were perceived the way Native Americans were in the 1950s US, you know, with great prejudice. I felt that in my family growing up big time. My dad, he yelled at me, he used the derogatory term for indigenous peoples whenever I was doing something that showed any hint of indigeneity.

Sure.

As a child, I was naturally interested in things like making shelters out of leaves, or catching insects, and in general living out the stories my indigenous grandmother told me. You have that stuff deeply embedded. My family was just a whole dysfunctional thing that I don’t want to get into—there’s a lot of pain in there!

Yeah.

I did eventually decide that I was willing to unravel this whole family history thing, unravel my indigenous culture. I wanted to try to be proud, rather than hide being an indigenous person.

Of course.

I’ve long admired indigenous communities and their relationship with the land. Long before I even understood that my grandmother was indigenous and what that meant, she told me all these amazing stories and planted the seeds of my love for the land.

Some of these stories were just wild: one of our heroes, who I’m named after, Kiliii, he was the Ulysses of Nanai/Hezhe culture, and he traveled around looking for a way to bring fish back to his village. On the way he passed by sirens who were actually seals dressed as women, in women’s clothes, to lure him to his death. And he rode on the backs of orcas to get where he was going.

Living Wild

And these are the kinds of fables your grandmother raised you on, basically.

That’s right. Much of my early childhood was my grandmother raising me without my parents watching, because they were too busy.

Sure.

They were working hard on their new careers, and they just dumped me and my brother at the library for 15 hours a day sometimes. My parents changed their careers late in life, and they decided to become doctors, but not until their thirties.

That’s crazy.

So that was rough when they had the two of us kids, while going through medical school and residency and all that.

Just never there.

We basically raised ourselves with our grandmother around some years.

So I finally did face up to all those things, and tackled the indigenous side of me, and learned to be proud of who I was. Living as an indigenous and Chinese-American person openly, it’s been really powerful, but getting there really sucked at the time, ha!

I’m sure.

I think in many ways my identity has become even more jumbled, but I’m glad I went through that. It made me a better artist, certainly, and it made my life better.

Because you were finally able to allow both sides of yourself to be shown through the work.

Yes, that’s right. Definitely it informs not just the work that I do, but also how I think of myself and how I interact with the world. I find that I’m far more compassionate now, now that I have seen so much of the world, and spent a lot of time with indigenous communities. I’ve seen the injustices that have been done to us, you know, you’re surrounded by people who have a lot of injustice in their history, but for indigenous peoples, it’s really fresh.

Return of the Condor

And ongoing, right?

Yeah. It’s very recent, and the more recent the wounds are, the more you can feel the pain of the people and the culture.

I’m thinking of an example of recent colonization that impacted me deeply, from my friend who is a French photographer, Pat Vack.

Mhm.

He’s French, but he lived in China for over a decade, and he recently did a fantastic project on the new Silk Road in Western China, recently published in Time. His project is amazing—in it there’s a single photograph that’s affected me deeply. It’s a photograph of an ethnic Kazakh in Western China. He’s ethnically Kazakh but lives in China. Western China has of course long been taken over by the Chinese. It was once mostly Muslim peoples over there, but China discovered that there’s tons of oil, most of the country’s oil is in that region. Now there’s a bunch of Chinese who live over there, and a lot of them were sent there by Communist China to be settlers.

Sure.

So there’s these rich enclaves, and the oil industry is really rich there– it’s the highest per capita income anywhere in China. Here’s the crazy part– the Kazakhs are not allowed to work in the industry. They can’t do any of the things that are making everyone the money over there.

Right.

They’re basically all the support; they’re cleaning houses, they’re taking care of the machinery. The other part of this vision I’m building is that Western China is also conducive to growing cotton.

So this photograph that I’m going on about has a Kazakh man who is standing with great dignity, in a uniform, and he’s standing in the middle of a cotton field with a bag full of cotton. It’s looks like it’s straight out of the 1800s during slavery.

Right yeah, back in the South.

I was just like oh my god, that’s so devastating, it’s so powerful.

And I assume they let the Kazakhs pick cotton.

Right, sure, of course!

I see what’s going on here.

I mean yeah, it’s not exactly the same, but that image gives me goosebumps, because that’s super-fresh colonization.

Right, and it’s happening right now.

It’s happening right now. Just having that symbolism there was unbelievably powerful for me.

But yeah, I think that’s why I feel more compassionate now, is because I understand that the pain I felt as a mixed kid is the same pain everyone else has endured as well. All these cultures that have been stomped on, they have really made me open my eyes and see the world differently.

Has it become difficult to continually immerse yourself in cultures and peoples who are experiencing that kind of trauma? The kind of ongoing victimization by other forces?

Definitely. Definitely, it’s hard, but working with indigenous cultures the pain is usually quite buried. It’s usually not as symbolic or as immediately evident as seeing people working in cotton fields!

Right, but I saw you were at Standing Rock last year.

That’s right. And you know, you see a lot of grief, but a lot of times mostly hopefulness. I tend to work with cultures that tend to be role models for other native cultures, often remote ones that have some central traditional aspects that are unbroken.

In the case of The People of the Whale, the Iñupiaq still hunt whales and they have never stopped. Because they’ve never stopped hunting whales, that part of their culture is super alive and it’s the keystone. You pull out the whale and slowly their culture diminishes, it crumbles. So when you look at Native North America, if you look the tribes who have lost their lands and subsistence rights, they have lost a core part of being indigenous—the relationship with the land. Of course there is a strong Native identity there, but at the core, there’s something missing that everyone is trying to get back. It should come as no surprise then, that Native Americans have the highest suicide rates and the highest rates of poverty…

Standing Rock

Right, suicide, alcoholism…

Right. So I tend to work with those cultures that have a lot of hope in them, because the despair, I think is something Westerners really like to concentrate on, and they really want to look at that. When you ask indigenous communities, they, for the most part, they want to portray messages of hope. They are not concerned so much about how they’re seen by the outside world, they’re really concerned, as am I, about how young people of their own cultures are seeing themselves. That matters a whole lot, and when I do a story, or put out a film or something that the world is going to see, I’m thinking about, what the public is going to see, but I’m also thinking just as much about how the youth of their own culture are going to see it. I want them to think to themselves, man, that hunter in that movie is my uncle and he’s a badass!

Haha!

Look at him, he’s a movie star, essentially. Even if the youth who see the work don’t know the exact faces in it, they can still say this is how we live, this is my culture, I’m proud of it because look at how awesome it is.

Right. There’s a celebratory quality.

Yeah, and it gives it legitimacy to see it in media, and that’s a really big thing now across the world. Indigenous youth are looking at the internet, and the TV, and they’re just forming these ideas about who they want to be and who they should be. When they find they can’t accomplish that, when the colonizers won’t let them do that kind of thing, then some end up committing suicide. This is not a tolerable situation.

My generation is getting it back. People who are my age and younger, a lot of indigenous peoples are now educated who have gone to cities and gotten educations and brought it back, are relearning the traditional culture. As a result, in many places there’s been a big push towards cultural revitalization, which is helping. So it’s really inspiring to see that’s happening just about everywhere.

Standing Rock

How do you determine where you’re going to go next for your projects?

People of the Whale was interesting to me because I’m also a traditional kayak builder, and arctic Alaska is the last place on earth where people still build traditional skinboats, or umiaqs, which are the big brothers of the kayaks. So that was a logical place for me to go. As a culture, they are a role model for northern peoples– everywhere people look to the Iñupiat, oh look they figured it out, they did it right.

Right.

They successfully fought for their land rights. They taxed oil drilling in Prudhoe Bay, they made money off of it. Their communities are in excellent shape. They have among the lowest suicide rates for indigenous people across the Arctic, no small feat given that the region has the highest suicide rates in the world.

They’re thriving.

Yes, the North Slope was a logical place to go, and Iñupiaq speak English, so it made it easier to immerse myself and be a part of it.

One thing I didn’t really see, we’re not generally very gear-oriented site, but what kind of preparation do you do, equipment-wise, for such extreme environments, compared to Seattle?

Initially, I spent time up in northern Scandinavia, in the Scandinavian Arctic, probably my first steps into the Arctic were in Iceland. Iceland is essentially the baby Arctic, or Arctic light. You can go up there, and because there is a lot of infrastructure, even though Iceland is very big, the landscapes are huge, you’re never really that far away from services and help.

top: Íslandia, below: People of the Whale

Right.

It’s much milder than the rest of the Arctic because of the Gulfstream, so it’s warmer in Iceland than it is in almost anywhere else in the Arctic. I did a lot of camping and road tripping and shooting, and you learn what it is you have to do. I found that in Alaska, which is much harsher, people recommend stuff to you, and you pay attention to what people are wearing and what they’re doing.

One of the things that was a surprise to me was how important it was to have boots that had liners, those liners that you could change out. Almost anywhere you go in the lower 48, when you buy snow boots, they do not come with a removable liner. With boots for Arctic travel, you can pull out the liners, hang them up to dry, and stuff in a new pair. That makes a huge difference because the moisture in the boots will freeze, and your feet will get really cold!

Yeah, yeah.

It helps to not do a project in an extreme environment, for a month to start, but to make initial explorations that are shorter to learn from. One of the hardest things with People of the Whale that I couldn’t learn from anyone else was how to manage my gear out there.

One of the big problems is that when I’m on the sea ice with the whalers, I don’t have the option of carrying more than basically what is on my back. In the event of an emergency, and there’s a lot of things that can cause an emergency up there, if the ice starts to break, you’ve got 5 minutes, 10 minutes to get off the ice before it falls apart.

There’s no packing your stuff up.

There’s no time for any of that. The other thing is, your stuff is the lowest priority of all. Saving everyone’s life and the boats and everything, those are the highest priorities. My gear was the least priority. So I always had my gear prepared to travel, all 40 pounds of it. If stuff wasn’t hanging on me, it was on my back in my bag, and all my bags were waterproof. I don’t tote around Pelicans because you can’t run with a Pelican. Instead I use an F-Stop backpack, which is modular, and I can carry it all if we evacuate off the sea ice.

People of the Whale

Have you had to do that before?

Yes, we did have to, this spring, we had to evacuate off the ice. It was an incredible experience. When you sleep in the tent, the rule is that you sleep with all your clothes on, you sleep inside your parka, inside your boots, so in the event the ice starts to break, you can go immediately.

I was on watch when I saw one of the guys coming down with the snow machine and waving, and he was like “We’ve got to go!” And we had all been on edge because we knew the ice was breaking, we were getting close to it, everyone was watching the cracks all the time. You could feel it, the ice was starting to move up and down a bit more, and that’s just a creepy feeling because you’re standing on 3-foot thick ice. You forget that you’re actually standing on ice over the sea– it feels like solid land, until you start to feel it moving up and down. That’s bad news.

It was also freaky to feel the tension of the whalers, who generally never show fear or anxiety about anything. I wouldn’t say they’re stoic, but the sea ice is their home. When I felt the tension in everybody else, I was like oh god, this is truly a dangerous situation. We managed to throw the tent and everything into the umiaq and get off the ice before it cracked off, and it took less than 15 minutes. I was really glad that I only had the camera on my back and everything else was in my bag, so I could just throw it on, throw it on a sled and travel.

Do you find it easy to ingratiate yourself into these communities, like what’s your process there?

Yeah it’s certainly easier for me than a non-Native, but trust still takes a long time. I think in a lot of ways, cultural stories like this are probably more time-consuming than anything with the exception of maybe some types of wildlife photography.

Sure.

I spent 6 months over three years with the Iñupiaq to be able to finish this story, and I will keep going up there.

Because I am indigenous and people recognize, especially northern peoples, they see it in my face and they recognize me, it’s a bit easier. They understand that I already know the rules, that things make sense to me that don’t make sense to non-Natives, generally.

People of the Whale

Right.

You have to pay attention to different things than Westerners are generally used to, and know how to take care of yourself outdoors. Also it helps that I just have a friendly personality!

Yeah!

I spend a lot of time listening and watching, and playing with the kids, and hanging out and definitely helping out. Over time, that trust builds up. It does very much help that you stay for a while, you leave, but that you come back, and you keep coming back. It’s the coming back that really helps to build the trust. When people see you year after year, even when they’re least expecting it, they remember. There you are again, you’re part of this community.

The classic photojournalist’s approach is, a lot of times, to be the fly on the wall, but that doesn’t really work for indigenous cultures.

Right.

For subsistence communities in particular, you cannot be a fly on the wall. If you’re a fly on the wall, then they’ll kick you out. It’s like what are you doing here, there’s no purpose for you here, all you are doing is eating food and making things more dangerous for the rest of us.

No tourists.

Yeah, that’s right. So when I’m up there, I’m doing everything that everybody else is: breaking ice, and staying on night watch, all the stuff that you have to do. I’m essentially at the level that a teenager on the whaling crew is. I’m on the crew learning, doing what all the greenhorns are doing. And on top of that, I have to take photos.

Ha! Is it difficult to balance that?

Yeah, there’s definitely times when I wish… during the ice evacuation, for example, I wish I was taking pictures.

Haha!

I missed some of the most hair-raising moments with the camera, but if I had shot them, I would never be allowed on the ice again. They would never ever let me back out on the ice, and worst of all, if that happened, we might still be out there, we might be floating around on the Arctic Ocean.

Yeah, you’d be putting people in danger.

That’s right.

Do you also get to come away with these new skills?

Yeah!

left: Return of the Condor, right: Standing Rock

There’s also this kind of added bonus for you of not just documenting the certain activities, but you also get to learn about whaling.

Yes, very much so. And that part I absolutely love. A big part of being an indigenous person, I think, in general, is understanding our connection to the land and how it makes us who we are. Subsistence is a huge part of that, and learning how to do all those individual skills. For me, competence outdoors is a huge part of my values.

Sure.

It’s fun, too, on occasion, because of my background in kayak building, that I can also teach Iñupiaq certain traditional techniques. Because of modern conveniences, things are done a certain way now, and especially young people never learned how to do some things the old way. So when things like nails, for example, aren’t available, we’re out on the ice, I can help them craft, put together sleds and repair things without those modern tools.

I looked at the video for the kayak company you run, do you think that same sort of craftsmanship carries over into your work?

Oh! Good question!

Mhmm, it’s what we do here!

Yeah, that’s great! I say the process is similar. When I started building kayaks, it was a bit haphazard. I’m a big fan of ‘good enough’, and that’s one of our mantras with kayak building. Kayaks were originally built on beaches with stone tools.

They would never be perfect, yeah.

Yeah, that’s right, so ‘good enough’ is important, but over time, I’ve also learned that you refine. I mean, you build 10 kayaks, you build 50 of them, you build 600 of them, and over time, you just can’t help but be more and more refined with the work. That’s certainly true with photography, too.

When I started being a photographer, I dived right into the technical end of it, I got into studio light and that sort of stuff, and that was great to learn a lot of the technical skills that I needed. Even so, the refinement of photography is really in the aesthetic vision and in the mind, how to see it, just like with the kayak.

You can build a kayak, and after two or three, you know how to construct a kayak the traditional way. But you’re not going to have a kayak that actually paddles well until you’ve made a lot of them, and you’ve tested them, played with them in all kinds of conditions, and you’ve bailed, and you’ve been thrown out of the boat in a stormy sea. You’ve got to make those mistakes and learn from them.

What is it that you’re looking for when you put your eye to the viewfinder?

I would say most of the time, almost all of the work happens before I put my eye up to the viewfinder. I tend to be looking at light, I tend to be looking at gesture, at what people are doing, and of course the meaning of things. Meaning is always in the background, for me, so I’m always thinking about why is this important? Sometimes there’s an infinite number of pretty things to shoot, especially in the arctic!

top: Gift of the Red Salmon, below: Living Wild

Ha!

A great example of that is, I’m using a drone as an example, because it’s different than a camera, it’s a flying camera…

Yeah, but the interaction is very different.

Yeah, that’s right, but it’s the same thought process that goes behind framing an image with a drone as it is with a camera.

I was flying around; I saw a whale tied up at the edge of the ice. In the back of my head I’m always looking for the moments when Native people express their spirituality. Because we tend to be very pragmatic and to hide our spirituality, we don’t wear it on our sleeves.

“We” as in modern, western culture?

No, I mean northern indigenous cultures, we in general, tend to not wear our spirituality right in front of you. With the possible exception of shamans, for those cultures like mine that still have them.

Mhmm.

Shamans see the world…

It’s their job.

Yes, our shamans, whose job it is to publicly perform and commune with spirits, they talk about spirituality in this matter-of-fact way. It’s not with a New Age-y sort of vagueness. Spirituality is individual and internal.

In the back of my head I am often thinking, how can I find a visual way to portray this, because it’s unspoken, it’s invisible. So I was flying my drone around, and I flew it over to see this whale that was tied up next to the ice from above. The composition was really beautiful, there was just a whale tied up next to the ice, and the shapes and everything were nice, so I just hovered there waiting for a while.

This is something that Sam Abell teaches, he’s a former National Geographic photographer. A Sam Abell thing to do, is that once you’ve found a beautiful composition, you just sit and wait and wait. So I flew the drone around and just shot video and I waited and I waited. When you wait, most times nothing happens, right.

Sure.

But in this particular instance, Flora, one of the female whalers, walked up to the edge where the whale was, and she spread her arms out in this kind of cross shape, stared out over the whale. I had seen this before a few times, always a moment when it’s a celebration, a thankfulness. It’s saying thank you for the gift that you’ve given me, whale. To an outsider who doesn’t spend enough time with the Iñupiaq community, it would just be like– what are you doing?

People of the Whale

Right, it wouldn’t have had any significance.

She just stood there for, maybe a minute, just holding, not moving just right there, and I took a photograph of her right at that moment. It’s one of my favorite photographs I’ve ever taken. It’s not perfect, the light isn’t that good, and all kinds of things, but the meaning is there.

Right.

That elevates it to a different level.

What got you into utilizing drones in your work?

I think because in the Arctic, everything is really flat, and to be able to look down on it is very different. The Arctic is such a huge, spread out open area that to be able to get a sense of how small humans are within it, flying above is really powerful. And also, showing ice, which is central to everyone’s lives up there, it’s way better to be able to look at sea ice with a drone rather than just from land, you can’t see very much, you don’t have the sense of the bigger picture.

The scope.

That’s right, the scope of it. Yeah. I actually, I’m a bit hypocritical about it, I actually really dislike drones, too!

Ha!

I fly them, but I’m that guy, even to myself. I’ve been in deep, but really beautiful places and remote wilderness, then all of the sudden heard the buzzing of that hornet’s nest drone, and I’m just like no, I want my EMP gun! But no, I’m that guy!

Is it challenging to use it in that kind of environment?

You know, you cannot show up on the sea ice with the Iñupiat and not have them not know you already fly a drone with expertise. People will literally shoot it down.

Oh man!

Of course, I have permission from the whaling captain and from all the people who are relevant. There is also a formal permitting process, there’s a substantial permit process for the Alaska Whaling Commission. I have to pass through all those things before I can do any shooting, but once it’s approved, then yeah it’s no problem.

Yeah. And something else that occurred to me: is this your full time job? Or is it the kayaks, mainly, and this is more of a…what percentage of your life does photography occupy?

The kayak business has been with me longer than I’ve been a photographer. I’ve enjoyed it for a really long time, and when I went commercial, I reduced the business down to one building workshop a year, essentially, just to keep doing it because I really love it. When I moved into documentary, it became pretty much impossible to live off that alone, but the kayak business kept growing. I kept developing it, and thankfully my girlfriend and partner, she has made the business boom and done a lot of stuff so that I can just be there to teach and build boats and be done with it.

So it’s her full time work and my part time work, but yeah, certainly for the amount of effort that goes into it, the kayaks make way more money than documentary photography does. And you know what, I’m okay with that. Aside from the fact that documentary in general, the industry is really in terrible straits, I’ve found that the stories that are the most meaningful and the most important are not the ones that tend to be popular. It’s not that they don’t get picked up, they do eventually, but they’re just not as popular.

Right.

It’s also hard work pitching stories before I actually work on them. So I’ve learned over time to just go after the stories I really want to do, shoot them, and shoot a bunch of side stories at the same time. Once I’ve got some work done, I can pitch multiple stories that take place in the same locality to a bunch of different editors, and a lot of times several of those will get picked up at the same time. That way I have the ability to sell additional stories or additional stock from that to support the main project, which is important.

Yeah.

Ultimately, no one would be telling these stories at all if I didn’t make them happen. And I look around and look at the work that other excellent photographers have embedded and spent time to tell the truthful, authentic story, an empathetic story is what I meant to say.

They’re almost all there for another reason, or they have another primary theme that kind of feeds into that place. For example, Hamid Sardar, he did work with the Dukha out of Mongolia, who are a reindeer herding people, and his photographs are amazing. He’s photographed one of the last shamanistic cultures in the area. But he’s an ethnographer, and his PHD is in the languages of Asiatic cultures of the region.

A very popular PHD.

Yeah, right!

Everyone I know has that, it’s crazy.

There’s not much left!

Haha!

So yeah, he got his PhD there and he speaks several of the languages there. So he’s able to do that work, be paid for it through research funding, and able to shoot photographs, as well, and that’s the only way he’s able to spend enough time there to have an empathetic look at it. I think these days, it’s very difficult to be able to do that kind of work otherwise.

66°33'N

Were there any photographers in particular you looked up to as you were developing?

Yeah, I think actually a lot of my early inspiration was a lot of commercial photographers. But slowly, documentary photographers’ work started to trickle in, and that became more powerful. But honestly for commercial photographers, Chris Chrisman is excellent, and Eric Almas, they have very controlled, highly composited images with a ton of retouching, but they’re beautiful, and they’re nostalgic, and they speak to tradition. In documentary, I love Erica Larsen’s work, and also Mattieu Paley’s work. I think a lot of my photography is informed by the kinds of work that people do who are in the same field, but also by work that I don’t like.

You see what they do, and you try to not do that.

Yeah, that’s right. There’s a well-known photographer from National Geographic that used a lot of artificial lighting. Initially, he was a hero of mine just because of who he was, not necessarily the work. When I started to really look at the work, I was like you know what, I just don’t like this work! It’s an aesthetic that doesn’t appeal to me. When I look at it, I see the technique, I don’t see the image. Or the image is secondary, I see the technique first.

Sure.

I mean, that’s a photographer thing to say.

Definitely.

But still, I want to be transported beyond that, I want to be transported beyond those things. I want the content to be so powerful that I don’t think about the technique, or at least not for a while.

Was there a conscious attempt on your part to move away from technique and more towards that kind of emotional impact?

Yeah, I mean yes, I wouldn’t say that I necessarily have gotten there! But yeah, I’m certainly thinking about it. I find that in order to be creative sometimes, I do have to think about technique. I have to think about technique in order to break me out of the molds of how I shoot, because if I don’t think about technique, what happens is that the technique I already have replays itself. Thinking about it forces me to reframe, to rethink about how I shoot and what I’m doing.

Because I’ve seen a fair amount of work of people doing more documentary stuff, and they tend to focus so much on what the subject that they forget about the technique, or making the shot actually be appealing, or engaging, whereas your work is on the surface engaging, and then the further levels of the actual subject matter.

Aw, thank you, I appreciate that.

It is a story well told, you know, versus, well the subject should be enough.

Yeah, that’s right. Well, I will say, just picking the story in general means that I have so much connection to it, and I love the subject matter so much already.

So when I’m actually shooting, that’s when I’m thinking about the technique. But in the back of my mind, before I put a tripod on the ground in the first place, I think about meaning and storytelling first. That’s the first part of the equation. The second part is how do I shoot this in a way that is different than what we have all seen before, you know.

Yeah.

You wouldn’t think that much has come out of shooting in the Arctic, but there’s lots of work from the Arctic.

And I think that, strangely enough, I think that is a question that people don’t ask themselves all that often.

Ha!

How can I do this in a way that hasn’t been done, or that I haven’t seen.

Yes, that’s right.

Especially with the internet, and Instagram, is that you see people kind of recycle the same techniques, trends, styles.

Certainly, yeah. The internet, it’s really powerful if you’re learning, but it’s also, once you get past a certain point, it’s a terrible thing. It just drags you into this weird little echo chamber. You know, if I see another photograph that’s ‘cinematic!’

Ha!

I love to subscribe to newsletters of different photographers and just kind of see what kinds of stuff are being produced. It’s interesting to see the trends ebb and flow and go back and forth.

I found that going out in person to, say, Review Santa Fe, the first time I’ve been to a major photo conference, I found so much inspiration there. The people who are present, the work that they’re doing is so different, it’s so amazing, very inspiring ways of looking at the world.

And the nice thing about doing it in person is that when you look at someone’s work in print, in person, you give it a chance. You give it an opportunity to stare at those images for 30 seconds or a minute instead of the two and a half seconds you get on Instagram, right. And it forces you to slow down and really look.

A lot of it is format, too, right, like Instagram is this tiny thing. At Review Santa Fe, I’m looking at some of these prints that are huge, 3 x 3, and there’s just an immense beauty to it that wraps you and envelopes you, you can’t ignore it. Yet if they were tiny, they would be completely dismissible.

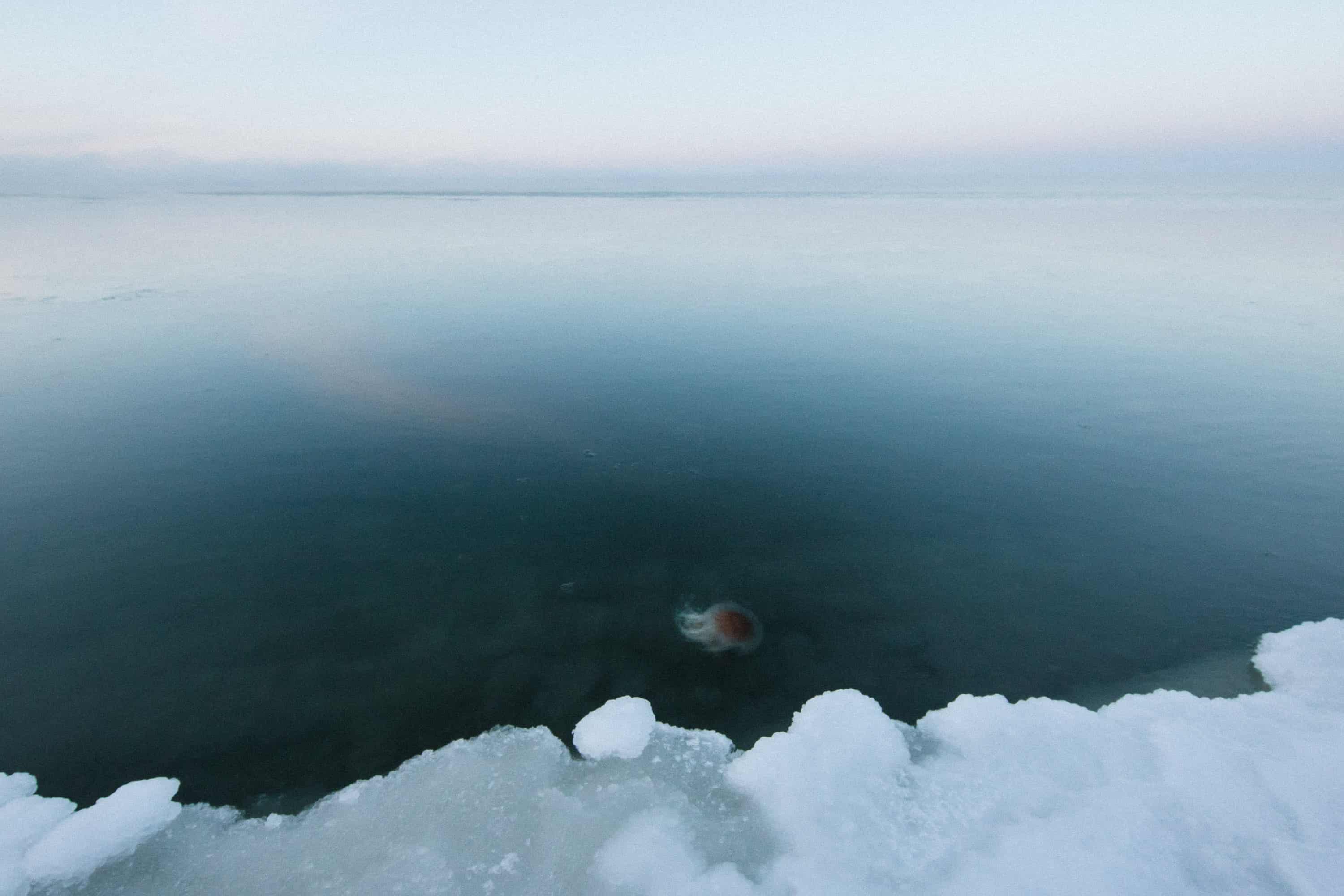

People of the Whale

Yeah, whereas the photo isn’t given the chance to be as powerful as it is because it’s just too small.

That’s right. Yeah, I tend to be really drawn towards things that are quiet. Quiet and make you feel small, you know, kind of lost in the power of the natural world. So the internet is especially not a good medium for that, right.

And you’ve got action shots, but they’re not these loud, blockbuster style shots. You can still kind of feel that quietude.

Yeah that’s right. And you know, sometimes I do shoot those action shots, but I find that I always edit them out. I always edit them out, they just don’t appeal to me.

Yeah, there’s a whole other, in your trash, there’s just, it’s an action movie the whole time.

Haha, right.

Part of the storytelling is what story you want to tell.

That’s right, yeah.

And the last question would be, and we ask this of all our interviewees: which do you prefer, the process or the result?

Oh man, wow.

Yeah.

Definitely the process, there’s no doubt about the process, for sure. I like the result, but typically for a few seconds! I think this is a personality thing, and I think that a lot of us who are artists have this type of personality. I’m one of those people that doesn’t like to celebrate. I don’t really look back on a body of work that has been accomplished. 2017 has been a good year for the People of the Whale, and it won a lot of awards, but I never really stop and pat myself on the back!

Mostly I’m just like, oh, I’m on the right track, that’s great. Now how am I going to translate this into the next project? Now how do I find a publication or the venue for people to see this work? It’s always just the next step ahead. It’s a little bit of torture!

You can never just be satisfied with it.

Yeah. I’m sure, I’m sure you understand!

People of the Whale

Oh sure, oh sure. Do you have another project lined up?

Yeah, I have a big one coming up in March, the next project is on suicide in the arctic, which is why I was talking about some of the suicide issues.

You’re switching to something very light hearted, something very airy…

Right! It just gets heavier.

Haha!

And it’s going to be hard, I already know. I already am daunted by the prospect of doing this project, but I’ve taken some inspiration from Lynn Johnson’s series on PTSD. She did a project where she gave veterans masks, and basically did this sort of art therapy and had them paint their masks.

Hmm.

And a lot of them painted these things where they showed their brain leaking out of the side. It’s an expression of their soul. They did these masks, and Lynn made these environmental portraits with the veterans’ families at home.

Externalizing that kind of interior life their experiencing.

Yeah, yeah. And it’s really powerful stuff and so I’ve taken that to heart. I’m piggybacking on that idea, but more specifically for the Arctic, which has the highest suicide rate in the world. It’s almost entirely indigenous youth, indigenous teenagers, which is crazy. In some of the small towns in Greenland, a teenager kills themselves every couple of days.

And actually, I had listened to a podcast about that maybe a year ago, that very same thing.

Yeah. Was it Embedded?

Yeah, it was! It was haunting.

It is. It affects me personally–suicide affects my friends and the people I love across the Arctic. But on a brighter note!

Puppies!

Ha! The project after that, I’m working on the book that will incorporate my work with kayaks with kayak history. It will look at how kayaks and skinboats are being looked at across the Arctic for indigenous peoples who are bringing it back. So I am looking at how everyone is revitalizing it. I’m going to Greenland this coming summer to look at that.

Nice. And that does it, thanks so much!

Alright, cheers! Bye! Thank you!

top: Íslandia, below: People of the Whale