Interview 092 • Jul 14th 2024

- Interview by Asa Featherstone IV

About Gabriela Hasbun

Gabriela Hasbun is a portrait photographer whose work shines a light on marginalized and unexplored communities. With a background shaped by her upbringing between Miami and war-torn El Salvador, Hasbun understands the critical importance of documenting the humanity in those often overlooked by society. Her photography career is driven by a fundamental belief in the transformative power of storytelling.

Links

Foreword

Black Cowboys are having a moment right now, and I’m here for it — with music, films, fashion…everything! It seems like Gabriela’s photobook, The New Black West, where she documented The Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, was released right on time, but she had been photographing this community long before things hit the mainstream. Her photography has always focused on highlighting what she calls micro-communities.

Her willingness to jump into unfamiliar spaces allows herself—and us through her work—to be surprised and grow. We had a conversation about her first time discovering Black rodeos in the Bay area, building trust with communities she’s unfamiliar to, and how growing up in El Salvador shaped her artistic direction shaped her artistic direction.

----

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

Were you photographing before you moved to San Francisco?

Not full time. My first encounter with photography was in a black-and-white film class I took during my first year of college in El Salvador. It was this Jesuit school, so pretty strict.

At the time, El Salvador had just undergone a 12-year civil war, but I was too young to fully understand what was happening. The school was very left-wing, and socialist, so they had a lot of photographic documentation of the civil war and of the massacres that had happened. So, in the beginning, photography for me was very much about recording and learning histories and stating facts.

I was able to get financial aid to apply to go to school in the States, and I moved to New Orleans. It was at another Jesuit university, Loyola. Through a work-study, I was able to work with a staff photographer in New Orleans named Harold Baquet. He was this amazing black photographer on staff at the university. He was obsessed with music and photographed all these jazz musicians on the side. So, I spent my time organizing the hot mess in his office and making black-and-white prints for him. Little by little, I started to love photography more. I ended up getting my degree in business, but I really didn’t want to work in an office at GE or something like that, so I finagled my way to San Francisco to do a year of photography school.

So, you didn’t grow up with anything related to photo before that one class?

Not really. I didn’t have parents who pushed me really hard – they were very free range. I was the last of four girls, so they only really cared about me getting grades similar to my sisters. I didn’t have an opportunity growing up to experience a lot of extracurricular activities or anything like that. My sister studied graphic design and had a Canon AE 1 left over. So eventually, that’s what I used in that college class in El Salvador. It was so old and beat up, though.

That camera’s iconic! A lot of people’s first cameras.

I know! Now they’re trendy and expensive. But I’m glad I found photography because I needed it to figure out who I was. It helped me consolidate my personality, my values, and understand what kind of stories I wanted to tell.

I love that. How did you narrow your focus to communities and people?

Well, I’m an extrovert! I love people, learning about cultures, and connecting with others. But I realized early on that I didn’t want to become a photojournalist. I ended up working for Ed Kashi, who’s a pretty recognizable Nat Geo photographer. I saw how hard it was for him to be away from his family for many months at a time.

I felt like I’d already lived through a lot of chaos in El Salvador as a kid that impacted me, and I didn’t want to photograph that. I wanted to photograph joy and celebration, so I started figuring things out through editorial work. I also knew there wasn’t a lot of money in photojournalism and I needed to sustain myself. Living in San Francisco, I ended up working for Newsweek, Forbes, and Wired photographing a lot of men in tech. As you know, that doesn’t fill your cup artistically. Spending 5, 10 minutes with someone super-important didn’t feed my long-term purpose.

Right. So how did you find non-tech communities that were interesting to you?

I started finding stories locally that either interested me or that I got assignments for and wanted to dig deeper into. For example, I read a little article in Marie Claire magazine in 2006 or 2007 about these fat activists who had gone out to City Hall to protest being discriminated against because of their size. I was so fascinated and had never seen this group before, so I kept an eye on them.

And —I don’t know if you believe in the power of manifesting— but lo and behold, this editor called me from the SF Weekly telling me he has a story that he thinks I’d be great for. And he’s like, “There’s a group of fat activists doing all this work that I’d love for you to cover.”

I was like, “No way! You have got to be fucking kidding me.” So, I got to meet everyone through that assignment and really bonded with them because, you know, I grew up in a family of women who are all overweight and it’s also been something that I’ve struggled with.

Long story short, the fat activists are people who I consider friends now. I spent all this time with them afterward and I didn’t stop photographing them after the assignment ended. It was something that I just kept doing to expand on the work that I made when I first met them. So, documenting these communities is just about showing up again and again, you know?

You do a little extra credit at the end. Why not just move on after the assignment?

I think it has to do with my personal curiosity. I’m naturally drawn to people and what they have to say. I think there’s always more story to tell. A movie or a book will never truly be complete because of that, right? There are layers to every story, and the longer you stick around, the more layers you can see. For me, that’s important.

I come from a really big family, and since most of my family is in El Salvador, I feel like the communities I spend time around can be looked at as my new family in a way. They embrace me for this period of time, and I feel comfortable and welcomed by them. So, if I’m being invited, why not hang out and share the pictures with them?

Good point. How do you go about establishing trust between yourself and the communities that you’re capturing when you don’t have a natural common ground?

I tend to use the same approach. Take the black cowboys I’ve been photographing in Oakland at the rodeo, for example. The first time I went, my neighbor took me in 2007, and I was like, “Oh my god, this is amazing!”. First of all, I had never been to a rodeo before that day. Second of all, it’s a black rodeo of all things. In my mind, it was insane, but very cool.

I went back in 2008, 2009, 2010. And even though I’d only see them once or twice a year, my method was all the same. After a while, everyone was just like, “Hey, it’s that photographer lady again”, you know? I just kept showing up and giving them pictures.

If Cowboy Sam wanted any pictures for his website, I could give him pictures for his website. I had been taking photos of a man named Joseph Duga and his grandson since he was, like, two years old, and now his grandson just graduated high school.

So, you’re seeing generations of family members go through the rodeo and that’s what the rodeo is. These families come together every year to celebrate with each other. It’s this wonderful community. And now I’ve taken my son to horse riding classes because of it.

The cowboys know me, but that took time. And as important as it is to take great photos, it’s also about showing up without a camera. I feel like a lot of photographers don’t understand that right now. They don’t understand that sometimes you can’t just shove a camera on someone’s face all the freaking time. That’s boring. You have to listen and be present. This work is personal, right?

That makes a lot of sense. Speaking of black cowboys, let’s talk about your book, The New Black West. Talk me through that moment when you saw the rodeo for the first time. What made you want to come back? What about it was special to you?

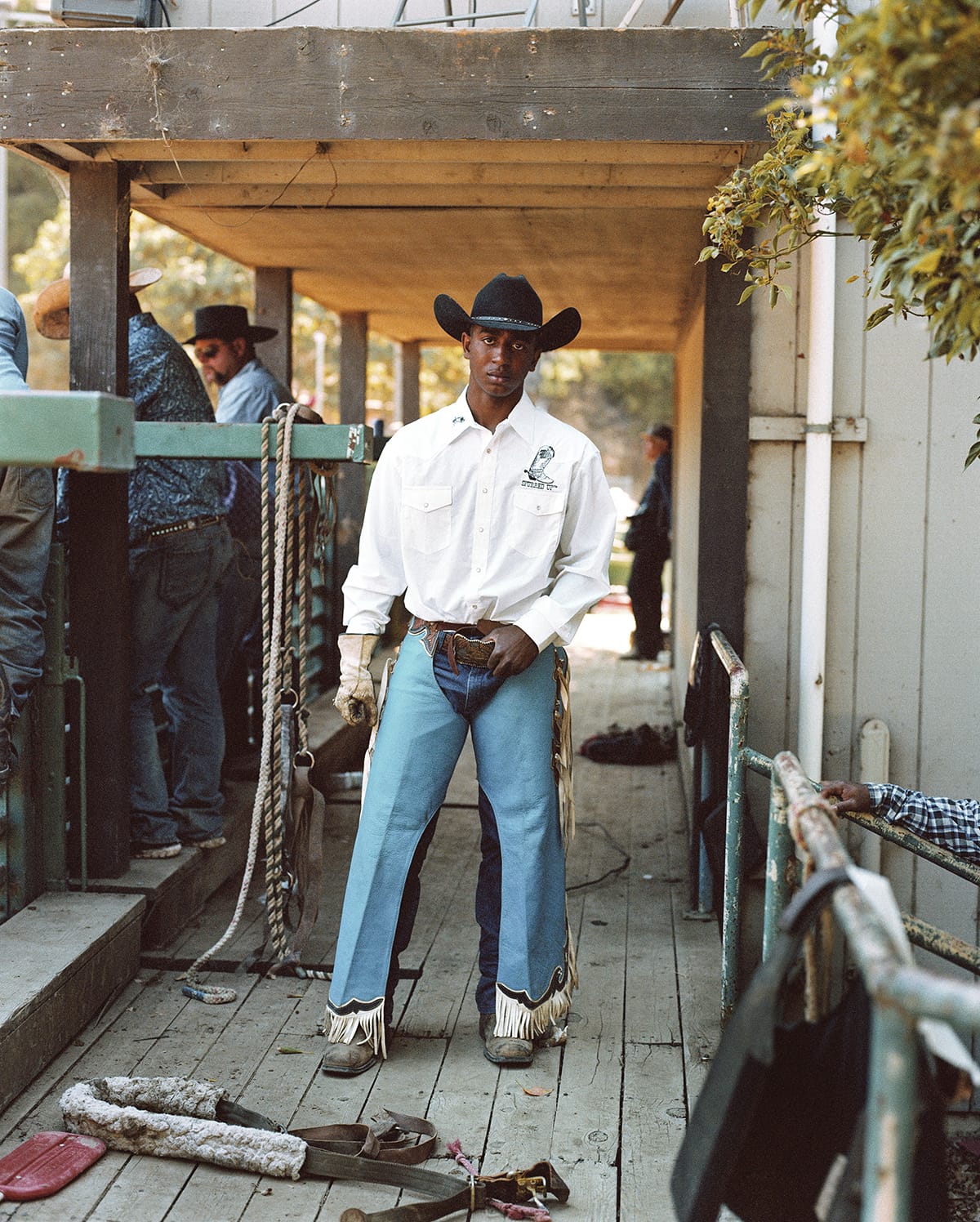

Everything about it was beautiful. The fashion, the horses. I was obsessed with the relationship between the horses and the riders.

How could this huge horse have such a calm relationship with a human? After a while, I just started learning so much about African American culture that I didn’t know about. Like, they have their own national anthem, their own national flag, and all these other things, you know. It was so amazing. I kept asking myself, “Why aren’t there more people here?”

Right!

So, it started out as just a fun project for me. I took my film camera (it was a Mamiya RZ67), packed some film, and my light meter. That was it. Every time I tried to get a press pass, Jeff, who oversaw press, would never give me a pass, so I would just sneak in through the back and keep doing my thing. I did that for years, but I eventually stopped going for a while after I had my son.

But when I got back to client work, I was feeling burnt out, uninspired, and needed to find something that reconnected me with my core values. So, I went back to the rodeo and started photographing again. When I came back, I noticed there was a whole new generation of cowboys and I started to make some new friends again.

It stayed fresh for you, that’s cool. Was there any hesitancy photographing the rodeo in the beginning since you were brand new to the community?

No, I just jumped straight in because it was just me having fun. The one thing I regret is that I didn’t take down names or phone numbers in the beginning. I never, ever thought I was going to make a book out of this work. Ever.

Haha. It’s funny how these things unfold, sometimes.

So, I fell so in love with photographing at the Bill Pickett, which is the black rodeo where I got started, but my husband, who grew up in the mountains, told me about another rodeo in Greenville. I immediately wanted to check it out and photograph it.

What was that like?

This rodeo was also beautiful, but so different, as you can imagine. I made a little promo piece for it on Blurb Books. I don’t know if you remember Blurb Books, but that process is very templated and about as much of a book as I ever thought I would ever make. I called it Young Riders.

Wait— so you have another book?

Haha. Technically it wasn’t a full book. I photographed it around the same time as the Bill in 2008 and 2009. This was published in 2009. I used it as a promotional piece to share with photo editors when I went to NYC to show my portfolio.

It didn’t matter to you that this was an entirely different community?

No. For me, it’s always been about discovering Western Americana because I never saw this where I grew up. This, in particular, was amazing and a completely different experience because it was up in the mountains. The photographs were much more focused on the topography.

Was your approach photographing that space in Young Riders any different than your approach for The New Black West?

Not really. It was still just me being a fly on the wall and roaming. I will say that people were a little less friendly and I didn’t really get to meet as many people, but I still loved the images I came away with. They felt beautiful and creative. But at the Bill Pickett, I felt like there was more to the story. It was this hidden gem.

I kept asking myself, “Why weren’t there more people coming? Why didn’t anyone know about it?” My black friends didn’t know about it, and my white friends didn’t know about it. I’m lucky my neighbor took me that first time.

So, I started pitching stories about the rodeo to publications like ESPN, and then San Francisco Magazine did something in 2018 or 2019, but by that point, everyone was getting woke, practically. By 2019, it was like an invasion of photographers and all of a sudden I wasn’t the only photographer anymore. I remember getting ready to take a picture and noticing like five other people with cameras right behind me. It was weird, I gotta tell you.

How’d that happen?

I don’t know. I think people were interested in black history and black culture all of a sudden.

Knowing what you know about the folks in the black rodeo, do you think they kept the lower profile on purpose?

I don’t think so. I think it was more about their capacity to promote. So, Jeff, who I mentioned earlier that was never giving me a press pass, is now a big supporter.

He was really hard on me early on and I had to earn his trust 100%. He made me cry the day he saw the book because he thanked me for being their advocate. It wasn’t an easy win, but he saw that time after time, I was trying to build them up, not take advantage of the situation. I was just trying to highlight them and use my network of clients as leverage so more people could see what they were doing.

Even then, it was hard to still get that attention. I still got a lot of no’s, but then I would try a different editor until they said yes.

When you get a no, what made you want to keep asking? Why was this story so valuable to share?

Because I think historically they’ve been marginalized. You don’t hear about positive black stories ever. You hear about a gang shootout in Oakland every minute of every day. They’re sensationalizing every negative thing that’s happening, but there’s all this amazing stuff happening and you never hear about it.

Here’s this wonderful thing happening with families, groups of firefighters, and nurses all showing up as a community, and no one cares. It gave me a shiver because something so good wasn’t being paid attention to.

Right.

But now people found out and they sell out like crazy, which I’m so happy for. It wasn’t until recently that they finally got a PR person. They had to because now they’re a nationally broadcast rodeo. They have more staff, but even still, there’s so few hands on deck. Like Danisha, who’s on the cover of the book, is at all of the rodeos helping out. Her mom’s a cowgirl, her daughter’s a cowgirl. And Valeria Howard-Cunningham, The Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo president and owner, is doing everything from selling t shirts, to running the video and camera department.

Sheesh, that’s so much! During that growth, when did you start to realize you were going to make this into a book?

After I saw how many photographers there were at the end of 2019. Haha! I had all these years that I’ve been photographing and thought I should do something with the pictures. They were no good sitting in my archive. I thought, “What if I could pitch it as a book, as a gift to these guys?” I had so many pictures and all the texts already written. It was just a matter of putting them together in a pitch format.

I started pitching at the end of 2019, and then the pandemic came, of course, so that slowed everything down. I had two interests, one from Chronicle Books, who the book was published in, and then the other one was with Harper’s Bazaar, but they ended up passing because they had published something similar, which I think it was the Compton Cowboys book. In the end, I feel really lucky.

How did you even begin to distill over 10 years of photographs into a book?

It was overwhelming, but ultimately I chose the pictures that I love the most. The photos that meant something to me, visually. And then I chose to put my friends in there. My cowboy friends. There’s an image that I love of the nails on the horse. It’s a friend that I made at the rodeo and every time we meet each other, we do something with her nails. It’s a staged shot, I won’t lie, but it’s our thing.

Some of my favorite images were created before 2010 because a lot of people would dress up to come to the rodeo. There was more of a formality and people wore more Western classic attire. People are a lot more casual now. You hardly ever see anyone wearing chaps or anything.

I love hearing about this. After all of this coverage, do you feel like people consider you to be the rodeo photographer?

Uh, yes and no. People ask me if I’m going to do another rodeo book, and I don’t know. I want to go back to the rodeo this year, at the same time, I don’t want to repeat myself.

You’ve spent so much time there, it’s almost like it’s just part of your lifestyle.

Exactly.

Thinking a little more broadly, have you noticed the boom of the black cowboy aesthetic? Lots of new folks are participating in Cowboy culture whether it be with music, fashion, films, or even art without understanding the origins. Do you have any thoughts on that?

I don’t feel like it’s appropriate for me to say because I’m not a cowboy, you know what I mean? But, I can say from afar that I think it’s great that there’s more attention on them because that means the rodeos are going to fill up and they’ll continue having events for years to come.

It’s a business at the end of the day, sure. The cowboys can make some money bull riding, barrel racing, or whatever. But at the same time, the point is for everyone to come together to see each other and to be part of this community.

It’s pretty funny though, every time a movie or an album comes out, all my cowboy friends get upset because they’re not telling the real stories. What’s the movie that came out on Netflix a couple of years ago? The Harder They Fall? My friends said they got the facts all wrong. Haha.

Haha. I can only imagine how much gets rearranged. Being from El Salvador, did your understanding of the American West change as you were making this work?

I’m not sure. I think I just started to uncover truth about the landscape. My approach was a little different because I didn’t have any background before going into this. I didn’t study the gold rush in high school, or grow up watching any Western TV shows, so I didn’t really have any expectations. For me, I was just blown away by the number of important historical black figures. I always wondered why they weren’t teaching this at school. Why aren’t these people celebrated? I just kept asking all of these questions.

Part of me was getting angry because we need more diversity in our role models and we’re not getting it. For example, Bass Reeves was a legendary sheriff—any boy would want to know about his incredible story, but hardly any of them do. A lot of TV shows were based on him, but they made him a white person. It’s frustrating to have your history overwritten like that.

Yeah, it’s tough and feels unfair, and you start to feel it more as you spend more time with the people who are directly impacted.

Yeah, it hurts to see.

I’m curious how you view your work. Do you prefer the process or the result when it comes to photographing?

Hmm. I like the process. You know, being on the ground, talking to people, being, enmeshed in my community. Those connections are what’s really important. That’s what makes me so interested in photography. That human bond.

When did you start to realize that your work was getting good?

Haha! That’s a great question, actually. Uh, it took a while. I feel like I’m a slow learner. Maybe around 2010, like it took like a solid 10 years before I started realizing, “Okay, this looks good.”

Was there a particular image or series that made you feel that way?

Yeah. I met a writer, Joey Plaster in like 2008, around the time when film started to switch over to digital. I really didn’t want to switch to digital because I felt like I found my voice visually through the medium format. Anyway, Joey had gotten a California grant to document Polk Street, which is this gay enclave in San Francisco.

Not a lot of people knew about it because it was overshadowed by the Castro district, the famous gay street. So, he brought me on to photograph this project, and it wasn’t a ton of money, but I was able to shoot it on film so I was happy to be working on it. When I shot that, it was one of the first times I remember saying, ” God, I really love how this looks!” It was just like how I imagined it or even better, you know? That felt really good.

Amazing!

I loved it even more because I was able to shoot it all on film. I think that’s why I ended up going back to photographing the cowboys again, because it was just me with my film camera. I felt like I did the best work because I wasn’t using all this other gear to fluff it up. It was just people as they are, doing their thing. I think at my core, I should have just been a documentary photographer. Haha.

And then you start to think about the money again, right?

Haha. Right. Especially living In San Francisco, you have to be a jack of all trades. If a commercial job lands my way, I’ve got to take it. You just have to learn how to do it all.

I hear what you’re saying about digital vs. film photography. Sometimes it feels like the computer is doing a lot of the work for me.

Well, there’s almost no separation. That’s why people say that the commute going to work is good, because you separate your home life from your work life. Back when I first started working, I would do an assignment, drop off film at the lab, and then go home. I’d come back the next day to check out the contact sheets and then FedEx an overnight envelope to New York. Then the photo editor would call and say, “Hey, I want frame 11 from contact sheet number 2901.” Then, I would take that info back to the lab. But now, there’s no separation between church and state. We don’t know what we’re doing anymore because we’re not able to focus on one thing. We’re the photographers, grips, editors, and retouchers.

You’re right. It’s almost happening too fast.

It’s crazy. If you’re doing a newspaper assignment for the New York Times or someone, they need the photos by the next day. So you’re going through anywhere from 200 to 500 pictures in a night. That’s hard for me because I get emotionally attached to people and I can’t separate what’s good or bad. I’m just excited everyone’s back into film again. I love that everyone’s feeling how fun it is to be surprised. It’s like going to the candy store when you get like that film from the lab.

Yeah, I think I really appreciate the slowness of film, and slow mediums in general. I’ve noticed people gravitating towards printed work and books just to add an additional dimension to the experience.

After putting this body of work together, have there been any other communities that you’ve been interested in documenting lately?

Well, right now I’m trying to figure out how to photograph El Salvadoran communities here in the Bay. El Salvador’s going through a bit of a renaissance for the first time since I’ve been alive. The country’s finally safe to live there and people are experiencing something that hasn’t happened maybe since my parents were alive. Peace.

I’m trying to figure out how to capture that visually, this time. I want to take a more fine art approach to this project, which is something I don’t do often. I’m also having a harder time starting it because I’m thinking about it too much.

Mm hmm. Have you gone back to El Salvador? If so, do you ever photograph there?

Yeah, I go back like once a year if I can. My sisters are there. My aunts are there. My parents passed away, but I have a lot of family there. I used to photograph a lot of the coffee farm workers in El Salvador, but then I just got tired because I would come back, pitch all these stories about coffee farmers and so nobody wanted to print them. No one cared about El Salvador unless it was related to the elections, which I also photographed.

My husband says I’m always 10 years ahead of the stories, because agri-tourism is a huge thing now. I also took a break because I was having a child, but now that my son’s ten, I feel like I’m ready again. There’s a lot more that I want to say.