Interview 078 • May 15th 2022

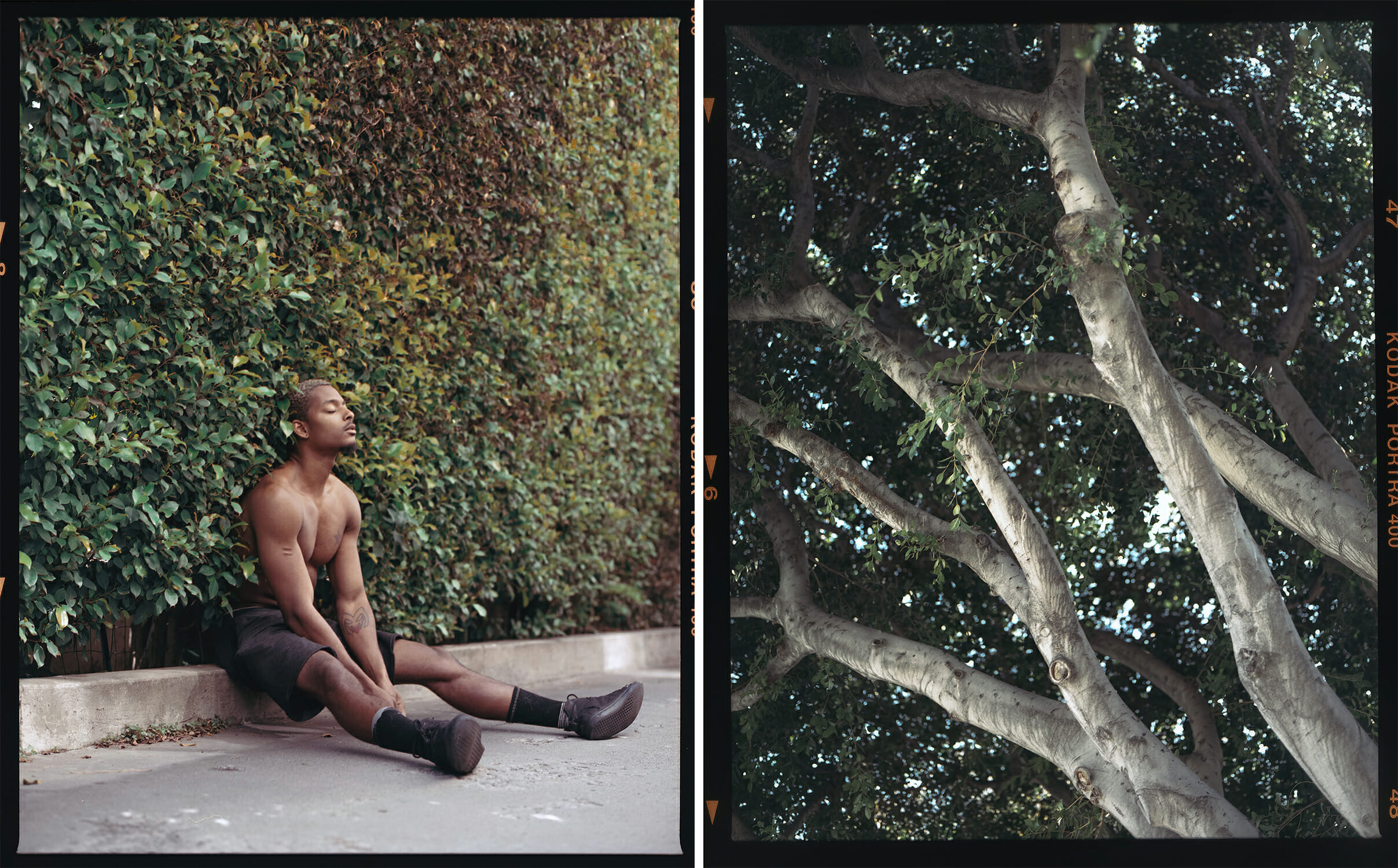

- Interview and Portraits of Erik Carter by Lou Noble

Links

Foreword

Getting to know Erik during the course of our interview brought deeper context to his work. His photography directly draws on his life experience, approach, and thought process — perfectly representing who he is and the subjects he focuses on.

Having the courage to explore themes and imagery that interest him has developed a guiding artistic direction for his career. That artistic focus enables a tender genuineness to his work that falls in stark contrast to much of the contrived photography we are bombarded with daily.

—

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview

You started in theater.

I did!

And you wanted to be an actor.

I did.

How did you find your way to photography?

Oh man. I went to Southern Methodist University in Texas, and probably around my senior year I realized that, as much as I love theater (I’ve wanted to be an actor or some form of a performer in theaters, since I was eleven), I realized that’s probably not going to the case.

Why is that?

Because well, that feeling that I had about didn’t exist at that time. And I don’t think, without that feeling, without that drive, without that true want to do it, you can’t do it. Like, no one can like shuffle through something so difficult and like, phoning it in. Yeah, no one’s phoning it in. Well, actually there are people phoning it in…

(laughter)

But, I digress.

You were not willing to…

I was not willing to phone it in, no. Nevertheless, I knew that I wanted to move to New York. So, I did that about two and a half months after I graduated and interned at a theater company. And I was taking photos here and there. I mean, I really started when I was in college.

Okay.

Because I was around actors and actors, not to call them narcissists, but they like to have their photos taken. So that was an interesting practice, I suppose. But while I was interning at this theater company, there was a need for a photographer for one of the rehearsals. And their normal photographer was not in town. And then someone said, “well Eric’s a photographer” or “Eric takes photos”, to say it that way, and see if he’s interested in doing it. And so I did that. And so that was kind of my first foray into the idea of having work that I could do that people would pay me for, and that was in like 2010-2011.

So at that point, you’re like 21, 22.

22, yeah. Yeah I moved to New York on my birthday.

Ah!

So it’s all the metaphors of rebirth and resurgence and all of that, let’s all put it together. But yeah, so that was my first idea of, “oh okay, so this could be a thing” So I started shooting a lot of different stuff. I started shooting theater performances, I started shooting rehearsals, I started shooting models and agencies and the whole photo-melting pot that comes with being in New York.

So as soon as that first chance to take photos on a more serious level, you just like…it clicked at that point.

Kind of? As theater was, was “leaving my body”, the creative spirit had to be replaced with something.

Sure.

And so, and I didn’t know it at the time, but everything that I had learned in school, because I had an emphasis in directing and playwriting, all of that informed my photography. So I took all of that and just ran with as much creative photography as I possibly could.

Did you have an interest in photography, beyond taking pictures? Did you look at other photography, were you a fan of it already?

Absolutely. I was a fan of it already, but I didn’t really know that I was, I mean so much of our lives we take in so much imagery. So my eye was already informed by…I didn’t know at the time but I really liked Irving Penn. I really liked Peter Hujar and I gravitated towards things that were slower because I also think that in theater and also in probably films that I admire, most of the things that I like are really slow, a two-hander, people just talking to each other, really small moments. So I knew that that was a thing that I was interested in, and I didn’t really start doing my own personal work until like 2012 when I was learning more about myself, while I was also learning more about photography.

Do you think that the photography was showing you more about yourself?

Absolutely. Yeah. I think this is a thing that quite a few artists, depending on the medium, say, but photography saved my life. I’ve dealt with anxiety and depression for the longest time, and so in New York, that is only made bigger and more specific. So to ease into New York, I was coping with a loneliness that I didn’t really understand and I was like, “okay, I’m going to start a project that is going to force me to go out and interact with people and talk with people and interview them”, and then from that, I inevitably would meet friends and then I would encounter other people through word of mouth. And so through that I was less so like a cage inside of myself.

Right.

So yeah, it was very, very necessary. And so from there, I realized…it’s so much larger than what we perceive. What we perceive is usually, you know, two centimeters by two centimeters on our phone, but I began to recognize the power of photo in the same way that I, early in my life, recognized the power of dramatic literature.

At what point did you start considering yourself a photographer?

Probably after I finished my first project. I was shooting for five different modeling agencies in New York, which at the time was fine. I get paid every time, they would come to me for new faces and that whole thing, which is fine. But I recognized that it wasn’t an artistic fulfillment. So, I started my own first project and when I finished it, it was this kind of body of work that I could sit with. And at that point. I was like, “okay, I’ve always thought of myself as an artist, even as a 12 year old,” which is probably narcissistic and a little bit…

There’s a certain self-awareness, even at that young age.

I would hope so. But after I finished that project, I was like, “okay. So this is, this is one, this is what I want to do and probably will do for the rest of my life. And I think this is something that I can call myself.” At the time, I was probably still working maybe three other jobs to support this.

Well, it is New York.

Right, it is New York. So I was doing all these other things to support the thing that I really wanted to do, but I knew at that point, that was the thing that I really wanted to do.

What other jobs were you working?

Oh Jesus Christ.

(laughter)

Man, I worked at a bookstore. I worked at Milk Studios. I was a bartender at four different places, at one bar I was also a pourer. So I had to get there early and clean the toilets and mop before starting a shift.

Sweet (sarscasm font).

I had to walk around Brooklyn covertly taking photos of every establishment that sold cigarettes, mark them in a GPS and then send them to some company in another state, which was the most bizarre thing. I’m sure I’m missing something but it was just a lot, catering. Yeah, I would try to do absolutely everything. It was tough.

Was it in an effort to experience different things or just to survive you were taking…?

Mostly just to survive. Yeah, never was it fun.

Right.

No, God I wish it was. Yeah. But if it was actually fun, then I probably wouldn’t have…I don’t know. Sometimes you do those things and then it’s good enough so that you just like stay in it.

Right.

Because it’s tolerable.

What was it that brought you here to LA?

So one, I was in desperate need of a change.

Why is that?

Well…I got to a point where my career wasn’t moving in the direction I thought it would.

Where was it moving?

I just, I wasn’t progressing at a pace that I thought…I was almost at 10 years. And I thought at ten years, surely, I would have a little bit more to show for than where I was at that moment. And I was working at a camera store, and it was just very specifically difficult because…I worked in the lighting department and there would be people coming in and they would say, “hey, I have this job with so-and-so celebrity for so-and-so publication, and I don’t really know anything about lighting. Can you teach me and tell me what I need to buy?” And so it’s one of those moments like, man. Okay. Sure. Yeah. Let me…

Just give me your job.

Right, right. That happened often enough, which wasn’t helpful.

No.

So it was that, compounded with just another, very specific form of depression. All of my friends had left, a few more friends moved to LA, they flocked. And a couple of them said, one specifically said, “you should probably move out here because I think your work lends itself here better because I don’t think people necessarily shoot like you here. Maybe there’s a little bit more room.”

Mhmm.

And I was like, “sure.” But the idea of that is you can put your faith into a place that’s unknown. Maybe I look better in this Alice in Wonderland place instead of this current hellhole. I knew that I needed like a big shake-up. So I kind of ghosted New York. I sold and I threw my stuff onto the street and what I could fit into a car, I just rented something, put in the car and drove to Los Angeles.

Oh wow.

Yeah.

How are you feeling about it?

Fine!

Two years in right?

Two years in. I do feel like I was leaving an abusive relationship. Just like putting everything in a car and leaving and aking the kids and going. That kind of situation.

You’re feeling the change worked?

The change definitely did work. I’m still adjusting to whatever LA is and whether or not I like it, but the change worked for me in terms of my career and in terms of space because the ability to come to a place like this. I mean, New York also has those places. It’s just the you are a little more landlocked.

Yeah, we got everything.

Yeah, there’s stuff here.

Did your work change when you came here?

Yeah, honestly, it probably got a little bit brighter.

Mhmm.

Strangely enough.

We got more sun.

It’s true. But brighter in every sense of that word.

Emotional.

Yeah, it just, everything opened up a little bit, which was very unexpected. So, I’m having to go back and go through the things that I’ve done in the past, well, since I moved here and it’s like, “oh, okay. Yeah, is that person smiling in that photo?”

(laughter)

Yeah, and I think that has to come with the territory. You know, let’s say I went back home to Texas for a while, my work would change dramatically.

How do you think it would change?

Oh it would it would be my blue period most likely.

(laughter)

Because there’s a lot of history there and there’s a lot of…

Trauma?

Trauma, there’s a lot of things to unearth and to investigate. And as much as I would want to, I could photograph a field of lilies and it would look so sad because that’s just what that land represents for me.

Do you go back and look at your old work a lot?

I don’t want to, I don’t like to. Some of the work that I’m doing right now, the jobs I’m giving myself, it requires me to go back and look at some things. But ordinarily I wouldn’t want to.

What is it about these jobs that require you to go back?

Well, one, not repeating what I’ve done, a lot of clients asking for a particular mood of mine and so I think, “okay. What are you referencing?” And so I have to go back and figure out what that is and then try to replicate that…only for them not to use that.

(laughter)

So yeah, a lot of jobs are like a forced recall I suppose, but I don’t really like to look at my work.

Why don’t you like to look at your work?

I never really have, I don’t know. I actually don’t really know the answer to that, I tend to just look forward. I’m also the kind of person, I think that when I die someone’s going to find 400 pages of a manuscript underneath my bed.

I like to make work. Sometimes I don’t care if anyone sees it. It’s about the process. It’s about the feelings that you get through it. It’s about who you meet along the way. The product is great sometimes, but it doesn’t supersede all that other stuff.

You would consider yourself more process than result.

Yeah.

It’s one of our classic questions. (chuckles)

Yeah, that is a classic question. I’m a process person and that’s probably theater training. But yeah.

(chuckling)

I truly thought it was an escape but it’s not.

Art?

Yeah, art. But you spend ten years of your life, probably 30 to 40 hours a week, doing a certain thing. It’s going to be with you probably for the rest of your life. Like, theater will live in me forever.

What is the appeal of tenderness for you?

Of tenderness. The appeal of tenderness…uh, God.

You’ve mentioned…

Truly, I truly have, yeah. It’s an innocence thing. Whenever it’s brought up…I guess I do that but I don’t think it’s something that I seek out. Not consciously, I think everything that works up to that moment, it obviously goes in that direction sometimes but I’m never, for the most part like, “okay, we’re going to sit down and we’re gonna have a tender moment together.”

You’re not trying to engineer that kind of moment during a shoot.

No, I don’t want anything to be contrived. I want it to all be organic. I’ll put things in place for those moments to happen, I suppose. But it’s not like I do a reference image beforehand. Like I want this to look like, Blue is the Warmest Color…

(chuckles)

All the writers for the most part that I have admired, people in interviews, ask them, “so it’s like, this character. What did you feel, why did you write that? And why is that about your dad?” And they’re like, “that’s not actually about my dad. I didn’t know that when I was writing it. I just sat down and started doing this stuff. Now what has happened in my life has informed that and that ends up being like a theme or allusion to my father, then sure, and I kind of I feel like that’s how my work works.”

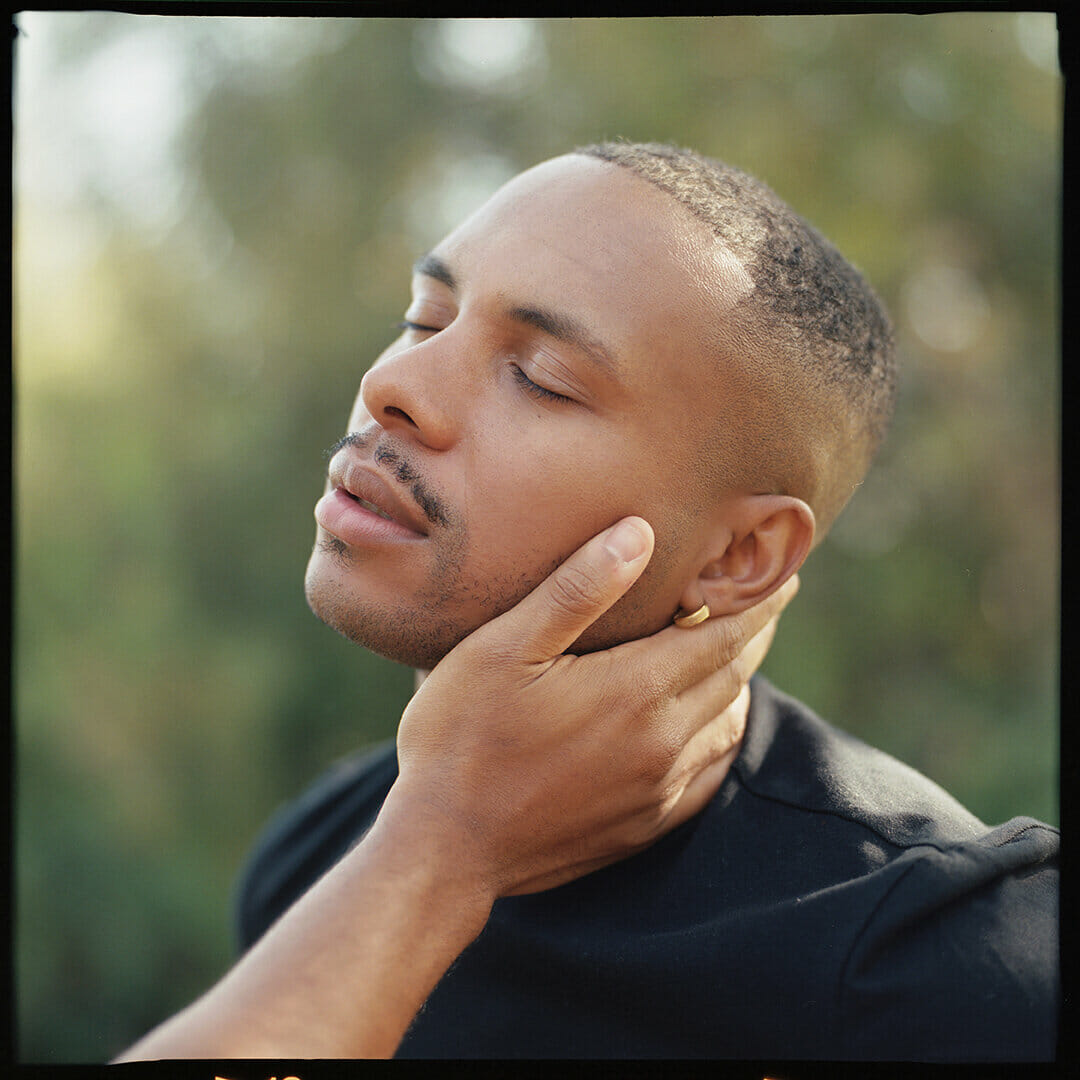

That being said, I think the idea of tenderness is important to me because I don’t think it’s something that most people allow for each other, and it’s certainly not something that I have allowed for myself. So it’s probably me trying to impose in a desire onto an image or onto a moment. I have my own things to deal with…like, touch is a very important thing. Touch to me is really important.

Would you say that touch is important in that you don’t have enough?

Yeah, I don’t have enough. I don’t have enough but also sometimes I’m afraid of it and when it does happen, it’s sometimes monumental.

Mmm.

So yeah, when that happens in a photo, if something as delicate as a hand on a collarbone or something like that, whether it be the subject’s own or another person, that’s important. Really small touches are important. I used to just, as one does in New York, you just watch people. So I used to go to Washington Square Park, which I think if you go to Washington Square Park, and you can’t see love in some respect…

(chuckling) It’s on you.

Yeah, then you can’t see it anywhere. But it’s really interesting just to watch subtle touches, hands going on the small people’s back or caressing the back of an ear, really, really small things that have really big impacts, so I don’t try to manufacture them in images, but I do put people in positions to make that happen. If you put someone close enough and you put two people close enough and you allow them to have conversation with each other, naturally, people will move their instincts will move to a certain point. And then from there, you can guide that.

Because ultimately, you are the instructor but the body doesn’t lie. So let them tell their own truth.

Yeah, you’re creating the sandbox for it.

Yeah.

As you toggle between personal shoots and commercial work, are you energized by both?

I guess, but really, it’s all circumstantial. It all depends on the job. I generally don’t take a job unless I’m interested in it in some way, whether it’s the subject, whether it’s the publication, whether something grabs me. Otherwise, it becomes way too corporate feeling, which takes away from everything.

That being said, every job I take feeds my personal work. All of that is in service of the things that I actually want to do. Granted, there’s a lot of client-based stuff that I want to do. But when I sat down and said, “oh, I’m going to be a photographer, this is what I want to do with my life,” the first things that came into my head, none of those really had anything to do with magazine publications.

What were the things that came into your hand?

They’re so small. Books, photo books. It’s a photo book in an empty room and just me to look at it. And I never thought of giant galleries, I never thought of any of that stuff, those were dreams and stuff, later down the line when I could even begin to start to conceive of such things. But initially I just wanted to make lasting, tangible work, and that was the exciting thing. And so that’s what I’m always searching to do.

Is there, like, a top of the mountain for you, right now?

The mountain, as I keep climbing these hills, the mountain gets bigger.

(laughter)

I’ve done some important things, I think. I mean, smaller things, to me, but nevertheless important. I would like to put out a book, I think. Probably before my parents die, I would like to put out a book. It would be nice…they still don’t know what I do.

You’ve told them and they don’t get it or they, you haven’t told them?

I’ve told them I’m a photographer and they’re like, “well, when you gonna get a job at a bank?” I’m like, it doesn’t work like that. So it would be nice to send them something of like, “hey, just sit down with this. And get to know your son.”

There’s a certain level of credibility.

Right. The credibility thing is something that they will never conceive of. I had a job that sent me to Paris and I was there, on the phone, in front of the Eiffel Tower, being paid to be in a place that you wish you could be in. And nothing. I just want something that has text and imagery, that they can sit down and get to know their son. And it’s weird. It’s weird to want that for me.

Is it? (laughter)

I mean, for me it is, because I just know, it’s because it’s not a validation thing I’m seeking.

It’s more understanding.

Yeah.

That’s seems foundational to a relationship with parents, that you want them to understand you.

Yeah. It’s helpful, it’s helpful for everyone involved.

If they don’t understand us, what is it about us that is so hard to understand necessarily?

Truly.

Or you know, what’s wrong with us?

Yeah, all those things, all those questions that keep you up at night.

When you were growing up, how did they feel about you being an actor?

Oh it was worse! (laughter)

What was it that you were supposed to be?

Anything else. Just something stable, something that could be in the white pages of a newspaper in the 1950s, something like that.

What do your parents do?

They are both retired now. My mother worked at a few different places, she worked at AT&T, I really don’t know their titles, she used to sub. And my dad worked at Kraft for 33 years on the line. They didn’t really talk about their work that often.

I decided pretty early on that I was not going to seek validation or permission from the people that I was supposed to, because that just wasn’t going to lead to any kind of happiness.

You read as much as possible and then you learn about the artists that you love and then you learn the things that they had to go through and you learn about what can come out the other side and then you pick apart what was successful, and then what wasn’t successful in their lives. So much of what I loved about New York was from artists in the seventies and the eighties. And you pick apart all the great things and then there’s all that other stuff that comes with it, mostly resulting in an early death. So, you know, you bypass all of those things…

Heroin!

Yeah, you skip the heroin, but you embrace the things that heroin can teach you? I don’t know.

Is validation something that you seek externally?

Yeah, I want to say no, but the fact that I am on Instagram or have a media presence at all, I don’t want to generalize, but like I feel like anyone who is on that platform is seeking some sort of validation.

Sure.

Me having Instagram is mostly to inform clients and people of what I’m up to, or to share something that I’m working on that involves a certain kind of community, to give light to them.

Do you have a photo community?

Yeah, I do.

And do you share with them?

I do not share with them. The reason I don’t share with them is because some of them, some of my friends, I feel, are so much further than I am. So for me to share with them…it’s a nervous feeling. It’s like, here’s this photo that is not as good as your worst thing.

(laughter)

So it’s rare that I will send a photo to a friend before I send it to anyone else. Yeah, I’ll let someone know what I’m doing that day. But I don’t necessarily show the results of it. I wonder what that says about me.

Has it always been that way?

Yeah. God, in college, I wrote an entire play that I didn’t want anyone to read, and then I just deleted it one day.

Oh my God!

It was terrible, a hundred twenty pages.

I’m big on keeping everything that, that’s…

Oh yeah. It was a weird moment. It’s a weird, weird moment.

You burned the laptop. (laughter)

Yeah, it’s gone. It’s in the ether.

Have you found a community here?

Finding community here, for someone like me, is difficult.

In what way?

In New York, I could stumble into people, even through photography I could stumble into a community. I had a studio in Bushwick, other photographers were in that studio, therefore…

You just bump into people.

You just bump into people. Here, it’s rare to run into people here. You have to really, really seek people out, but I have some people here. I have three or four really good friends here. And I think that that’s a really good thing to have. And they’re supportive. I think it’s imperative as an artist to have people in your life who are excited about your success as much as they are their own.

Mhmm.

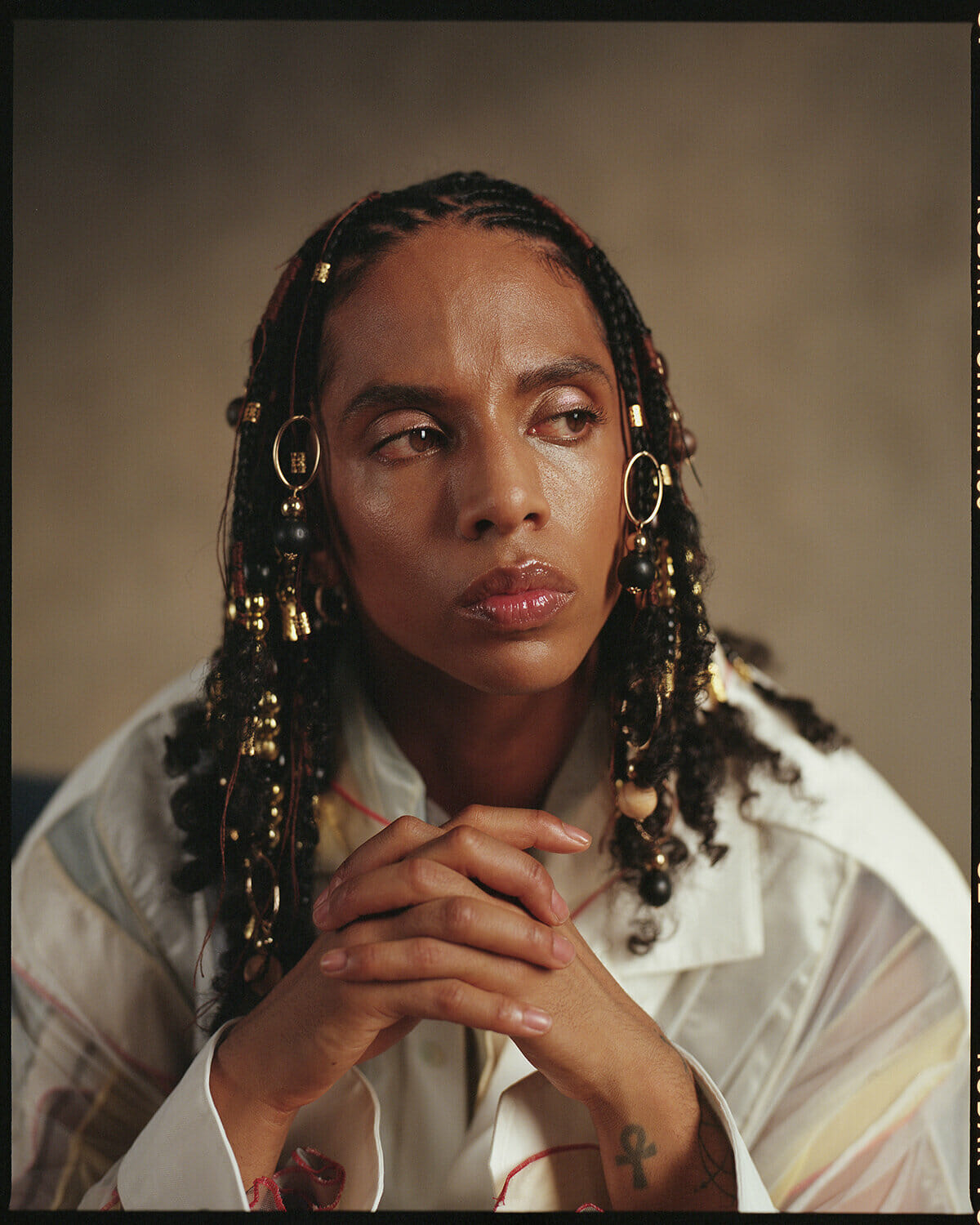

To have people who are championing you, especially for people in your own community. Like for black people, for queer people. It’s very important to have them with you on your side, and then to do the same for them.

Right.

Where do you find inspiration?

There’s a lot of stuff. But mostly in relationships, kind of in this. I find inspiration in talking to people, I find inspiration in the need; when I was growing up, I thought art, in general, was about revolution. I thought it was done in service of inciting change, inciting joy, inciting confusion, inciting something.

Where did that come from?

Watching anarchy videos. (laughter)

(laughter)

No, I read a lot of Baldwin, I read a lot of Brecht. I read a lot of those writers who were born in times of those needs and through their art made changes.

Yeah.

Or tried to make changes, whether that be in the United States, or in Berlin, or wherever. I always thought that that was the impetus for art, and so my inspiration, I would like to think comes from my own need to show any kind of change or prosperity or highlighting communities that are often unheard. I mean, that’s what I’m interested in.

I know that there’s that and that’s probably the main point and then all the other things, all the other inspiration comes from things like music and film, and my own personal trauma. (chuckles) I mean, that was my first project came from that.

What was your first one?

It was me going around New York interviewing and photographing gay men specifically about masculine.

This was Be Masculine.

Yeah. Back in 2013. That spawned from me not understanding what or how to be a queer person in New York, in my early twenties. I didn’t understand, because dating and romantic or platonic relationships between queer and gay men, for me at that moment, was at its best confusing, and at its worst abusive. So I was thinking, “I don’t know what this is, perhaps I can learn more about myself, through learning more about others.”

So the inspiration came from me trying to deal with my own trauma and my own personal demons.

What was it that was confusing?

For me, I guess people didn’t even really know how to treat each other. Also, there was just like profound racism between gay men from every side, it was so surprising. There was one particularly bad week that made me want to start doing that project and it just involves four really awful encounters. Yeah, I just thought, “I’m doing something wrong, right, or surely I don’t know something.” I didn’t have a good enough gay mentor apparently to tell me what to do.

(laughter)

So, yeah, through personal trauma comes inspiration.

And why do you find that project shallow, now?

I find it shallow now because the investigation of it wasn’t deep enough. The questions were fairly surface level, but they were, for me at that time, they were the necessary things for me to be asking.

Right.

I just think now, eight years later we’ve progressed. Whether or not those questions have been answered, they’ve been explored to death. There’s just so much more underneath it. Underneath what masculinity for queer people looks like, what masculinity for anyone looks like, I think that word in itself, hopefully, will be retired in the next five years, ten years.

Would you consider art cathartic and therapeutic then?

For me? Yeah, yes. I’ve come to discover many things about myself through the work that I’ve done and also just the work that I’ve seen. But in the process of doing it, you gain some perspective about who you are and who you want to be. And then also how people are treated, how they want to be treated, how they want to be viewed, how they want to be loved.

All of it sounds so fantastical when I say you can find out how someone wants to be loved through an hour-long discussion and then photo of them. But there’s some truth in that. I mean you see it. It’s a weird statement to say, when most of the things that I see or that I’m bombarded with…

In terms of imagery?

In terms of imagery, are so glossy. It’s like no one really wants to be seen as themselves. Everything is a manufactured chimerical idea of who that person is. So, God, even when I photograph, when I photograph anyone, the main thing that I want to do is just this. A soft intimate talk, which is hard to do when there’s a PR person behind you saying you have three minutes, so.

Did the Be Masculine project help you with that, with those issues?

Yeah. Yeah…the beauty of that is that you’re getting a wide variety of subjects. So some of the internal questions or issues that I had about myself in talking with, I think one person lived in Long Island or something, in talking with him about his own problems, it, yeah, it helped me. It helped me tremendously.

Was dating and engaging with people easier after that?

Yes, like…the problems that I was running into before the project started, I knew how to avoid those things. Which of course invites new problems.

Of course.

And do I understand relationships and dating and all of that completely now? Of course not, who does. Nevertheless, I’m much, much better at navigating all of that now than I was before. So, yeah, that project, I was better on the other side of it.

Were there projects in which you were not better on the other side of them?

I mean, there’s one that I’m in right now that, I don’t know, I don’t know what it’s going to look like when I’m on the other side of it.

What’s the basis of it, if you’re…?

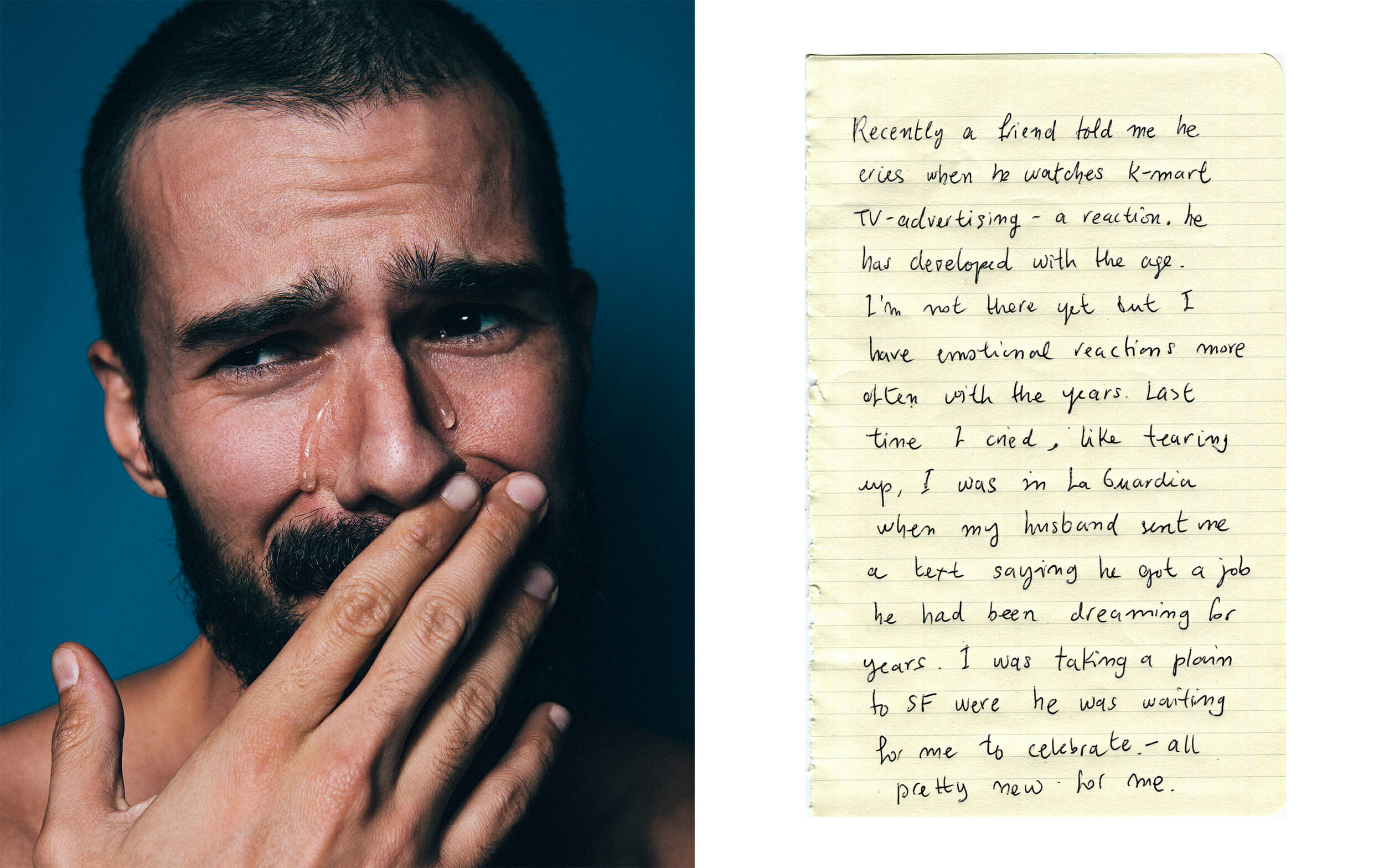

I found some writings that I did when I first moved to New York in 2011, when I wrote the bulk of them. And they are weird word vomit memoir things. And most of them are really sad, so I’m photographing what I can remember of that, so I’m essentially photographing depression, or what that looks like.

And trying to find the way on the other side out of that, and it’s just like, oh God, I have to remember all of this, so going back into that. But aesthetically, photograph-wise, it’s interesting because you take your own writing, of something that you don’t necessarily remember, but you have visions of those moments so you try to photograph what that emotion is and what it feels like, which means that you have to go back to that emotion and photograph it, so I’m doing that right now.

Is that involving people? Or no?

No, it’s the first time I’m being slightly abstract.

Was there an impetus for starting the project?

I don’t think so, I just, well…my Google Drive was running out of space…

(laughter)

And I thought, “what is taking up so much space?” And I went all the way back.

Alright. So that’s crazy.

What?

Because text doesn’t take up any space!

(laughter) I know, yeah.

I don’t like to call people crazy…

(laughter)

But I also know how small text files are. (laughter)

There were three text files, and then one looked like Zodiac Killer.

(laughter)

And then the other one is dated and it’s a full thing that I think I wrote in almost every day. I stumble across that, I think I read like one line, and realized, that’s kind of interesting, oh yeah, I remember what that was, I remember who that was about.

Mhmm.

Yeah, and so that rabbit hole just happens, “okay, alright, this is a feeling so I’m going to run with it, whatever that looks like.”

When you’re talking about the difficulty with celebrity, with PR, have you developed ways of evoking that in someone within those constraints?

Yeah, sometimes it’s successful sometimes it’s not, sometimes you have a subject who very much just wants to get out of there and there’s nothing you can do about that. But usually, when these people get to you, I shoot for the New York Times a lot and I shoot for some of those publications, you’re there they say, “go to this hotel room, you’ll have eight minutes.” There’s so many variables of things that can go wrong. So, you over-prepare.

Right.

Which is why a successful image in those situations…you may have spent five minutes, but your ten years of being in this business, have prepared you to do such a thing. I do my best to be as conversational as possible and there’s no hierarchy, there’s no ego really. I try to pair all that down as much as I can and just remind everyone to breathe. It sounds really simple, but it’s a really big thing.

Oh yeah.

Because a lot of times it’s a hotel room of a press junket. So when they get to you, this is the 19th thing they’ve done that day. And so, if they sit down and…I also shoot film, fortunately. So one no one’s looking at me, no one can see what I’m doing.

(laughter)

No one can see what I’m doing and it allows for things to be just a little bit slower. So you have a moment to just close your eyes and breathe, if you can do that for me, and then after that we can kind start taking our time and go.

In a situation like that, how many frames are you shooting?

Not many. The most recent thing I did I shot four rolls.

Okay. I thought you were going to say four shots.

Four shots! No, no. The, the smallest I’ve done is two rolls.

Okay. I don’t even know what kind of feeling was going to come up, like four shots.

Truly, I think I was looking at some old Jack Nicholson photos and, I don’t even know who the photographer was, but it was the full archive of this photographer and there was three images of that entire shoot.

Has shooting celebrities changed or adjusted your process at all?

In terms of how quickly I need to work, it has. In terms of how I have to approach most situations, yes. It also just brings up the topic of compromise, so often client clients will say, “hey, we really like your work, we want you to shoot in your style,” they’ll send me a treatment of my own work. And it’s all work that I like. It’s mostly film. And then we get there, they’re like, “great, so we need it to all be digital,” and it’s like, “here are these compromises and here are these stipulations and you’ll have 12 people behind you, looking at you making notes and things will get in your way.” So, shooting celebrities has informed my process of how to cut through all of that, which sometimes is easier and sometimes it’s nearly impossible.

Has it then informed your personal work in any way? Or is that a skillset that just stays with the…?

Yeah. Personal work stays intact. It’s stayed pretty true to form. Celebrity stuff, people who are recognizable. They, no, it’s kind of the same thing.

I shot something last month and this particular celebrity, she had been moved from this warehouse where she was filming this documentary, from one edge of this warehouse to the next, so by the time she got to me, she just sat there and was like, “what is this?”

(chuckles) Where am I? Who is this person?

And yeah, and I’m also like, what is this?

(laughter)

Client, what are we doing here? But yeah, yeah. It’s all bizarre. The other thing is, I didn’t realize that when I started shooting celebrities that that was, for some people, a dirty word in this industry.

Hmm, interesting.

That like, you’re a celebrity photographer, it’s like, I’m not really a celebrity photographer. I’m interested in everything. I shoot celebrities, sure, and I shoot commercial work, I also shoot personal work, I shot like a queer skate girl group that’s coming out in Huffington Post next month, if I’m interested in it, I’ll photograph it.

Right. And your interests are wide and varied.

Yeah. I didn’t realize how quickly it is to be pigeonholed. I had a job, it was a job that was tailor-made to what I do as a photographer, in my personal work, and then I had it and I was really excited, I was more excited for this job than I was for any job this entire year.

I already have a bad feeling.

It was gonna involve travel. I was going to get to go back home for a little bit. I was basically going to do a job that I was already going to do, focusing on a specific group of people in my community, but then this thing came up and was like, oh this is perfect. But then the client, I don’t know who dropped the ball, but someone didn’t reiterate or didn’t show them more of the work that I have done that is in line with they were doing, and all the clients saw was my recent celebrity stuff. And so they thought, “oh, he only shoots celebrities. I don’t think he would be comfortable photographing the ordinary person.” Just like, ugh.

That was really disheartening. I was really sad about that because it was like a job that I really, really wanted to do. But I’ll also say, if you can photograph, which I haven’t, whatever, if you can photograph a Kardashian, if you can photograph this complicated situation in this room full of crazy people,…

Sure.

You can photograph an ordinary, a normal person.

You said in another interview that eye contact for you is permission.

Right.

Yeah, I just like that (laughter).

(laughter)

It explains a lot for me. But I guess the question there, can you talk about the importance of permission?

Mmm! Yeah, I think that quote was in response to a trans strip…

Yes!

Yeah, right. When you are coming into someone else’s home, whether that’s an actual home or like a metaphorical home, whatever.

Their space.

Their space, when you’re coming into their space, and they get to control how they want to be seen, it’s so important to get permission from them. And that can be eye contact, that can be a non-verbal or verbal agreement of “yes, this is fine for you to photograph me in this moment, or to show me in this light, because this is the light that I’m standing in, this his how I want to be seen.” Because for so long, especially any marginalized community, many photographers go in there, they photograph people and then all of a sudden the world thinks that, you know, this group of people are thugs.

This is what they look like based on these photos.

Yeah, exactly! Oh God, what was I reading, something like when Reagan was governor or something, he was having a conversation with another politician, and they were talking about some recent National Geographic thing that they just watched, and talking about how black people still didn’t wear shoes, and we’re essentially monkeys, and it’s just like, great, cool!

(laughter)

Hmm. Like, National Geographic has since apologized for decades and decades of abuse of that kind of stuff.

Thanks (sarcasm font)!

Yeah, thanks.

(laughter) oh, it’s all, I feel better, then.

But those images taken without any sense of permission, essentially it’s violent because of what it does to those communities. So there’s a sense of permission when photographing people.

Even when you think that you are in your own community, you’re doing your own thing, before you go into a project or before you go into anything, ask yourself what you’re doing there, what you’re in service of, and then get the permission from the people you are photographing.