Interview 052 • Aug 17th 2016

- Interview by Lou Noble,

- Elinor Carucci Photographed by Sasha Arutyunova

About Elinor Carucci

Born 1971 in Jerusalem, Israel, Elinor Carucci graduated in 1995 from Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design with a degree in photography, and moved to New York that same year. In a relatively short amount of time, her work has been included in an impressive amount of solo and group exhibitions worldwide, solo shows include Edwynn Houk gallery, Fifty One Fine Art Gallery, James Hyman and Gagosian Gallery, London among others and group show include The Museum of Modern Art New York and The Photographers' Gallery, London.

Her photographs are included in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art New York, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Houston Museum of Fine Art, among others and her work appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, Details, New York Magazine, W, Aperture, ARTnews and many more publications.

Links

Foreword

Too often we see the fictionalized use of intimacy in photos...small windows into lives pruned and edited to make them the envy of all their viewers. And while some of these vanilla objects might pluck the yew of our voyeuristic curiosity, truly transparent work like Elinor's raises the work to an art form, accosting your senses with a raw guttural beauty.

- Agustin

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

It’s been two years since your last monograph. What’s your work life like, these days?

Yeah, It’s not much different because I’ve been doing been doing my own work for years. So I’m doing my own work. I’m shooting, I’m teaching in the MFA School of Visual Arts, and I’m the mother of two children, which is…a lot!

And they’re eleven, twelve?

Almost twelve. So there are times that are busier and times that are less. Overall, around the time of a show or a book there are more events, things to do. But I’m always making work and taking pictures and working on personal work and shooting for magazines…It’s just that when they’re s a book out or a show, other people get to see it. And then you go back to your private way of life. So it’s the same.

You’ve been shooting twenty-some years now?

Actually thirty, if you include the work I’ve done since I was fifteen, and I just turned forty-five, so yeah.

Have you noticed any changes in how you shoot your personal life?

Over the thirty years? Yes, of course! Many things happen, in a way. From things like moving countries, from Israel to America. Even the light here is different. The apartments here have less daylight, less natural light. Starting to work editorially, I learned about strobes and artificial lighting. Becoming a mother really affected who I am and what I photograph and how much time I have, and especially when the kids were younger, it was taking one frame, two frames. And even now, sometime I can shoot more, if it’s very quick. So everything affects the way I photograph. But I think in the very core of it, something remains the same for all those thirty years.

And what do you think that core is?

I can talk about it now, but when I started I didn’t understand why. I think the core of it is who we are, as people. In the microcosm of family and our closest connections. And it’s very hard, it comes from a very personal and intimate place. My work is really about who we are, it’s universal. It’s about the love and the connection and the problems and the flaws and the difficulties, losing people, becoming sad, becoming happy, becoming a parent, being a daughter. It’s all very universal. It’s just what it is for me to be a human being.

Right. Do you it’s actually made it easier being able to photograph you personal life, being able to deal with the hard times, to get through things by processing them through photography?

Who knows!

Hahahaha!

Each one of us has to find what helps them. I don’t know if it does in the way you’re saying, if it’s different from professional photographers these days, than all of us, we take pictures all the time, because we want to preserve what we’re losing. And we’re losing all the time. I sometimes tell my husband, “I don’t even know how we can go through the day knowing that every few seconds we could drop dead and die! Or our loved ones could drop dead and die!” I think that one of the ways that we develop to cope with it is to take pictures. Does it matter if I am taking pictures with the Canon 5Ds with three strobes or if someone else is taking snaps with their cell phone? In terms of the therapeutic part of it, I don’t know. But it is therapeutic for me and I think all of us to try to preserve those moments. To preserve and keep the memories and the pictures of the ones we love.

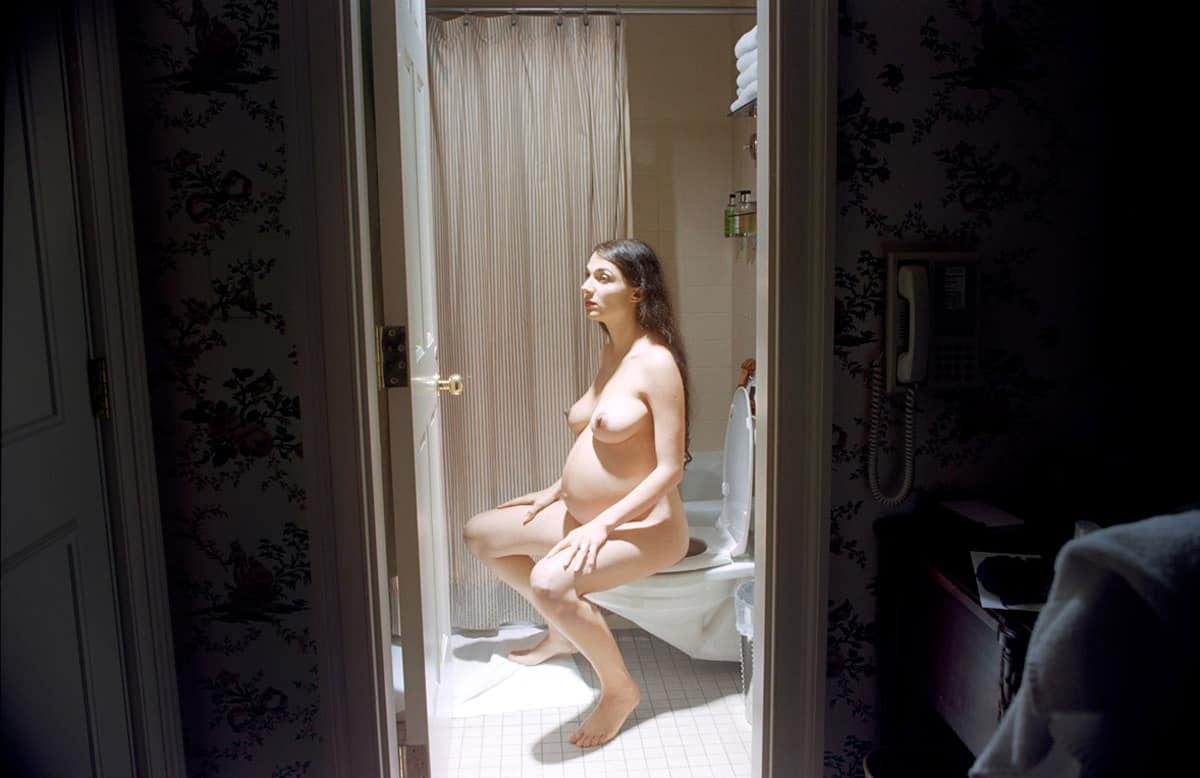

Selections from Mother – Elinor Carucci

That’s what I was thinking of, when I was looking at the pregnancy photos. As challenging as the pregnancy can be you have the photography to focus on.

In a way, that is helpful. Yes and no. On the other hand, it’s sometimes…a part of who I am to look at the painful things. Then to look at the file, and to make a print, I’m stuck with this thing!

Hahaha!

So sometimes it magnifies it, but I think it does help. I think what really helps, it connects me with other people, it connects me to the world. It’s like writing letters to whoever is willing to look at my work. And there is something comforting for me, reaching out and sharing what I’ve been through and what I think is amazing, what I think is painful. And there’s something about sending it out to the world and then getting feedback or some words. Meeting people and talking to people and colleagues, or people I’ve never met before. It’s somehow comforting.

What kind of changes have you seen in the response to your work? I know some of the subject matter read as far more taboo, fifteen, twenty years ago.

It’s hard to know. I’m trying to figure out the world today with all the selfies…I think, I can’t even make sense of it because in one way the world has become a little more conservative. On the other hand, we’re flooded by images of everybody’s life. I think it’s less of a big deal that I photograph my children than when Sally Mann did it. Because their friends are on Instagram, their parents put images of them on Facebook. So yes, they know it’s different it’s been exhibited shows and shown in magazines. Maybe it’s the facade of their lives…and this is what’s different, we share (and I hope it’s not the facade of our lives) the deeper, more honest real life that we have, while most people share events, parties, smiling. But yeah, it’s not as taboo, I think. Or maybe not. I’m not sure and sometimes it’s so overwhelming, what’s happening with images in today’s world. I just go back to…not hiding, but doing what I know for me is real or important. Because the world is changing all the time.

It also seems that, where people are now taking pictures of their lives with the frequency that you have, they’re still not as open as you have always been.

I think it matters a lot that you make the choice to become a professional photographer. I have to bring something better to my audience. There are many images that are meaningful to me, but it’s not enough. Or as sometimes my students say to me, “that really happened! I really felt it!” It doesn’t matter. I also know I have to create. I’m an image maker, a storyteller, I have to make it beautiful, aesthetic, conceptual, interesting. So I think it’s also that I’m showing more, more of the private but I’m also a professional photographer. I better make an amazing image, or no one will be interested in it!

Selections from Pain – Elinor Carucci

Hahaha!

It pushes me to…I devote my life to making images that are iconic, and deep.

What led you to teaching?

Actually, it was Steven Freeley…I teach in the MFA of the School of Visual Arts. I started in the BFA, the undergrad, and Steven approached me. And I was a little insecure, that was 16 years ago, so a few years after I moved to America, and I was a little insecure to teach a critique class in English. So I told him I’m not sure I can do it. And I remember he said, and that is really something that has led my teaching ever since, he said, “Let me ask you this: can you be generous?” And I said, “Yeah, I think I can be generous.” And he said, “so you can teach, and you’ve got the job. Congratulations.” And that was it. And I left this meeting thinking, “this is inspiring, challenging, now I better walk the walk.” It is a lot about generosity, in a way. It’s easier for me to teach people who are in my own…photographing their lives, families and talking about intimacy. And it can be very challenging to teach students that are doing work I do not relate to as naturally. But I grow and learn as much as them, if not more.

What kind of things have you learned?

You learn a lot about the different ways that people work. The different ways that they create art. What can be exactly the wrong thing for me can be the right this for another person. And you also have to be critical and honest. But you can’t be as dismissive as you are about, let’s say, conceptual work. Conceptual work is harder for me, especially if it’s colder, to relate to. So if I come to a show, I can be like, “oh it’s all crap, I don’t care, it’s all trends, blah blah blah. Who is this person? Who do they know?” This is the bad Ellinor. But when I teach, you have to bring another side out of you. You have to understand. I have to look at conceptual artists; I have to dive into who this person is, and what they want to do with their work. And sometimes I really switch, I fall in love with their projects, and I’m very touched and moved. And in order to help them grow I have to connect. Or, if I still think it’s bullshit, I have to tell them I think it’s bullshit. But many times it’s not, those are great projects, it’s just not my personal taste. So you have to expand yourself. You have to learn, you have to understand, so I think it’s on the art level, what is good art. And also on the psychology level. Who is this person? How do they work? What do they really want to talk about and how do I help them get there? So you learn about people and you learn about art and you learn about photography. And I also learn about all the new photographers or video artists, because they tell me and I write it down…I’m like, “who is this??” So I learn all the time.

What kinds of trends have you seen recently?

Right, and I think this is good and bad, that many times my students want to work more in installation, multimedia. So I see it develop, a lot of students don’t take photographs any more; they use images they downloaded from the internet. So I have also, in the MFA, there is Penelope Umbrico. I have studied her work and a lot of them look into what she’s doing because it’s a different approach to photography. But I also sometimes encourage them to pay attention to creating an image, if this is where they want to go to.

One other thing that occurred to me while looking at your work. Did you anticipate the possibilities when you were pregnant like, “OH, this is going to be a whole new area for to photograph.”?

Why do you think I had kids in the first place!

Selections from Mother – Elinor Carucci

HA!

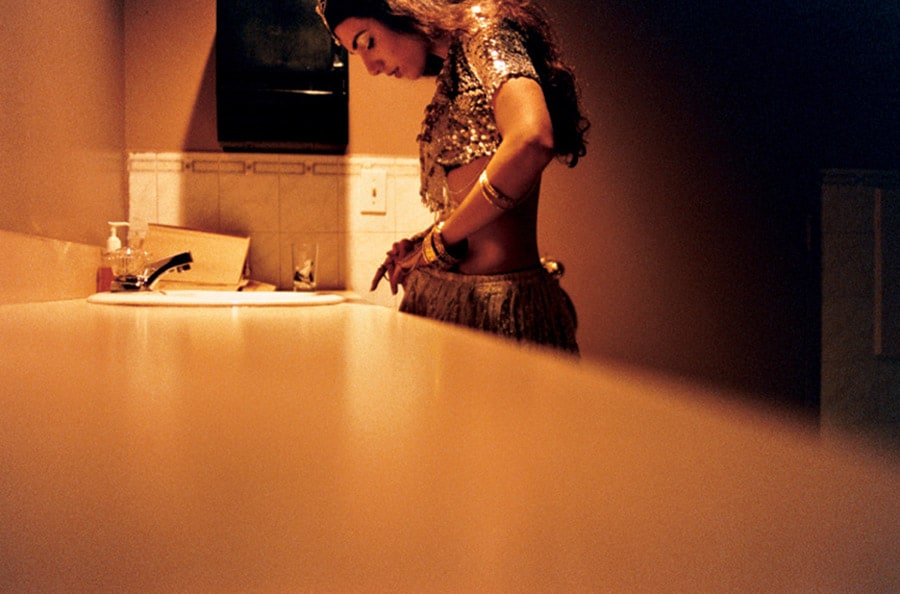

I moved to America with no family and I needed to create someone to photograph! Of course, I already know that the way I work, I usually don’t research and find a project to work on. It comes from my own life. It’s really whatever happens to me. When people ask, “what is special about you and your family?” It’s absolutely nothing. And that’s what’s special. That’s what makes it universal, if I had a problem with back pain, it became a project about pain. If I had a crisis in my marriage, it became a project about crisis. And again, those are things that are so universal. And I know that I’m going to follow what life brings me because, usually, and this is with exception of the bellydancing work, and maybe that was the reason this work was not as successful as Closer and Mother, because it was more specifically a story about a Middle Eastern dancer in New York City. But usually, whatever happens in my life, it has all the specific details, being pregnant, having children is the most universal thing I can think of. So yeah, of course I had it in my mind, but I had so many fears and worries and questions about being a parent, and that was one of them. Would I even still be able to work? I was scared. My family’s not here, and my husband’s family, they’re all in Israel; I have an aunt here, but the question was more than what you mentioned, about “will I make the project?” The question was, “Will I be Elinor?” You have so many questions…”Will I do a project on them” was one of many worries/questions.

Has there ever been a situation that you didn’t want to shoot?

Oh, I don’t shoot most of my life! 99.8% of my life is not being photographed. I’m not one of those people who carries a camera and takes pictures constantly. Not at all. I can have two or three weeks, not that I’m proud of it always, without I don’t take pictures. And sometimes I have to, as I tell my students, “go to the gym of photography.” Pull out the lights, make yourself do it. Because, when I stop taking pictures, I stop seeing the pictures….I start to not see things, and that’s why I started being a photographer in the first place. Because once I start taking pictures, and if I haven’t photographed in a while, I might just start with a boring picture, but then I start seeing things, and I get back into photography shape, so I tell it to myself and my students, “We have to keep in shape, we have to go to the photography gym, and we have to pull out lights and camera and take pictures.” But I’m not snapping all the time. And most times I will not take a picture, I am not constantly in my kid’s face with a camera.

Why did you choose New York?

Okay, so there are two questions here, that I always think about! One: I came for photography, of course. When I was…yesterday I was thinking about it. You know, the International Center for Photography opened their new space, so I was at the opening yesterday, and they’ve been very helpful. But when I was seventeen, I came to New York, I was already very much into photography, and I went to the ICP in the upper east side. You were a little kid, a long time ago!

Selections from Mother – Elinor Carucci

I was maybe 12…10…

A little kid! I remember being in the bookstore and looking through the books, and it was so amazing to me that there was a museum only for photography! You take it for granted, growing up in America. And even in school, we learned so much about…more because a lot of our teachers did their graduate degrees here in America, so we studied about American photographers and shows in New York, so for me, I was going to the center of the world for photography and I really wanted to be there. But it was not easy for me, it was really not easy the first few months, and maybe, now that I’m thinking about it, the first few years, maybe it was a decade, maybe until I had the kids. Actually, sorry to be heavy…

“Yesterday!”

Hahaha, actually, I’m moving back now!

Hahaha!

I think when the kids turned five and started going to public school, and I developed a community and a home, I think only then, and I’m talking about more than decade after I moved, only with them going to school and me hitting roots here, even though I had my American citizenship before, only then did I feel this is home. But then a very painful thing happened when I visited Israel, because it’s like you cheat on your country! I come to Israel now and I feel torn; it’s very complex. So I think also the question is I moved here for the photography, like many of my friends in their twenties who came to New York and went to school or did something for their career, and then most of them went back to Israel. So there are two questions: Why did I move to New York, and why did I stay.

Well, why did you stay, for all those hard years?

Do you have three hours?

Yeah, sure!

I think…it’s complicated. Yes, for the photography. Somethings are so painful in Israel for me, which is now starting to happen. Memorial Day in Israel for me was so painful, the reality of the soldiers that are being killed, and it was a little bit different here. Now, which I guess is a good thing, this is my home. And I was volunteering for Bernie Sanders, and it’s wonderful to feel connected, and to learn that now, so now I am angry about things that are happening here. Angry about the wars and about the fact that some of them that are happening that are not necessary. Feeling as big of a pain for when I hear about an American soldier who is killed or injured. So now I feel at home here, but home comes the reasonability of what do you do for your community. What do you think about the politics, about the economy, about the homeless people. So I don’t know. It’s complex. It took me a while but I traded one thing and another. But that’s the beauty of being at home. So I guess it’s home. And when I go to Israel now, I feel a little removed; I feel like a visitor, sometimes.

How do you think being Israeli affected your photography here? When you’re shooting people here, how do they react?

I think my work, which is funny, because I think many people see my work as not Israeli because they identify work that is Israeli with work that is political. And my work is not political that way, it’s not about Israel and Palestine. It’s not political in that way, but its very Israeli. I think it’s a misconception of my work because Israel is the family…it’s very familial. The family ties and connection are ties and Israelis are warm and emotional and dramatic. So it’s funny to me when I hear it, because I’m like my work is so Israeli. It’s so much about the warmth and family and connection and emotions. Maybe it’s Israeli and Jewish, maybe both. So this affected the work that I’ve been doing. Then my choice to be a Middle Eastern dancer is something that is also very popular in Israel. And that has affected me very much, because fifteen years as a professional belly dancer…

Selections from Diary of a Dancer – Elinor Carucci

You kept doing it after…?

Most of my career as a belly dancer happened here, actually. I studied it in Jerusalem at Arabesque Dance Company. Then when I moved here, I studied and started to perform a lot more on my own, for over a decade. And being a belly dancer, you’re usually not on the stage. It’s the good and the bad of it. It’s not regarded as ballet or even Flamenco. You’re usually at people’s events, family events, weddings anniversaries, birthdays. For fifteen years I had to go into someone’s living room and connect, feel the room, feel the people, feel who they are and open up to them. Have them open up to me. And it’s very connected to the photography that I’m doing with my own family and editorial assignments, relating to other people’s lives and families. And how to find the balance between being you, but you’re not the focus. And being sensitive and respectful to other people. When to try and get them to dance or when to try and get them to do something for the camera. When to leave them alone, give them a minute. Or just even say, “you know what, this is not the day for you to dance with me, this is not the day for you to be photographed by me. When to respect their privacy or a bad day or whatever it is they’re feeling.

Why did you stop?

Mainly because of time. I became a mom, and it was really hard. The photography was growing and I became more busy with photography. I had two kids; it was just exhausting enough to be a mom and a photographer, let alone all that and a dancer at night. It was really hard. I was lacking sleep. It was hard. From the beginning, the belly dancing was secondary. It was always the photography that I knew was the thing for me. And I had to separate.

Did you experience any kind of prejudice….did being pregnant hurt your career, at all?

I don’t think being pregnant hurt my career. It’s the core of who we are is our parents, where we came from, our childhood, our family. So to dismiss it as something women photographers do, when it’s really the base of who we all are over the world I think is terrible.

I wouldn’t ask that question of a male photographer but from what I’ve experienced there’s a prejudice. When women get pregnant it’s like, “oh she’s not going to be able to work anymore for a while.”

Right, there is that, and there is also focusing on your children. What I do know is if you’re focusing on your family, and I tell my students that, if you’re focusing on your children like any other parent in the world, if you’re photographing your children, you have to make your work extremely complex, extremely good. You can’t just take cute pictures of them. That’s true usually in landscape, or pollution in the town next to you. Everything today is being photographed by many different people, and it’s challenging to create work that is interesting. I don’t know if it was the pregnancy, and I don’t even know….when I live my life I don’t feel, I feel a lot of respect for a lot of people. But I do know that sometimes, less the pregnancy, more the choice to focus on family and children can be regarded as, in a negative way, as a thing women do, as not as important. It may be easier in terms of reception to do work that is strictly or directly political. This is something that I think is ridiculous. So at some point I think, “these are the trends right now, this is the world I live in”, and at some point I have to say, “I don’t give a shit.” I really do. I can’t keep worrying about it. This is what I do; this is what I believe is important. I believe I photograph the things that are most important to us as people. This is who we are, and the microcosm of family affects politics, affects everything in life. And let my voice be heard as honest as it can. This is my honest voice, is what I believe in, and then there is the world out there that…if I’m a woman, if I’m pregnant, that I have to deal with every once in a while, but many times I just say, “I don’t care.”

Has your relationship to Control changed, because I feel as a photographer we love the control of photography, as you’ve gotten older how has that changed for you?

Yeah…less and less control. Because with everything that I do, a lot more involvement and a lot more emotion, and you just realize, in my case, in the way that I work…it is different, in different disciplines, that…it’s a very humbling process, I feel, to be a photographer. You just realize that what life brings to you, whatever happens in front of the camera is many times more interesting or more important than anything you had in mind. So you have to find the balance…I definitely learned more about Photoshop and about handling or retouching my files. So I know a lot more about photography than I did twenty years ago, technically and the history, and with all that knowledge and dedication and emotion, I have to come to a shoot and just dive in. It doesn’t matter if I’m photographing a stranger for an editorial assignment or my own life. It’s all there, all the knowledge and the things that I want to say. But when I am taking the pictures, I jump into the water, and I’m swimming and diving and breathing, and I’m dancing the dance of art with whatever it is that I photograph. And I have to put control on the side because it’s there, anyway. All of who you are and what you think. It’s all there anyway, so you have to trust it, that it’ll come through and let life lead you.

Selections from Crisis – Elinor Carucci

So even more instinctual.

Yeah, a combination of being more critical of what I’m doing, with more knowledge, but it’s really different, what happens when I edit the work, when I retouch the work, when I print the work. When I approach people or write the text, to what happens when I photograph.

In some of the interviews with you, when you were pregnant and thinking about photographing your children, you talked to a lot of people about how to navigate that. Thinking of Sally Mann and the difficulties she faced. What kind of things did you discuss with people in regards to photographing your children?

I think there was a misunderstanding in what I said. This is what I said, when I started taking pictures of the children, I wanted to photograph, again, something very universal. It is about me and about other people. And at that time, the first few years with the children, more than talking to other photographers or other artists, my inspiration came from came from talking to other parents. Not about photographing children, but about parenthood.

Ah!

There is the image where my daughter sits on my lap while I’m on the toilet, something like this started to happen, and I wanted to ask other parents if it happens to them, as well. When you go to pee do your kids sit your lap while you’re peeing? And they’re like, “yeah sure, it happens all the time,” like 80% of mothers. Or the sensual aspect of having children, and how you even neglect your husband for a while, because you’re so physically and sensually fulfilled by your kids. I was asking mothers about that, and a lot of their honesty and openness about that made me…I don’t know why, I had this conversation with Tierney Gearon, and she said, “what does it matter what other people think? It’s about you!” But there is something in me that wants to represent also what I hear from other parents, fathers and mothers in my own work, especially when I feel it as a parent myself. So what I meant to say back then, that was my inspiration. A lot of what other parents are going through, what do they feel about who they are, who they are as a wife, as a sexual person. Who you are as an immigrant. What do they feel about being a parent. So that’s what I meant more than about talking to them about photographing their children.

I had my concern about that, and I did make some decisions about that. Like, not showing nudity of the kids, until they’re older. And I did discuss it with some people.

What kind of rules did you set for yourself?

It wasn’t even that I set the rules. It was that at some point, in a way, the mother Elinor and the photographer Elinor clashed, and the mother is stronger!

Hahaha!

Ha! So the rules are that life comes first, if it’s the kids or my mom. And sometimes the photographer is getting her way, “go away, let me take this picture!” Sometimes they live in harmony, and sometimes they fight. I’m a Gemini by the way.

So it makes perfect sense.

It makes perfect sense.

How has your relationship with your mother changed? Do you see the changes between you and your family photographically?

I think that I’m daring to show more of myself as a mother. Actually it’s a fact; I’m daring to show more of myself than anyone else. I know that I’m willing to show everything about myself. And it’s true for my husband as well; the poor victim for marrying me. And really there are no limits. So I think that has changed. We are different women that have raised children in different countries, in different cultures. But there is a lot of similarities. We are both…I come from a very open and warm, loving, close family. We are very close, and I’m the same way with my kids. Even I feel, sometimes, it’s not more or less, but because we don’t have an extended family in America, it’s even more of a tight unit.

Do you seek out editorial work that will allow you to investigate to the level of your personal work, or does it kind of come to you?

It’s a combination. It’s definitely the last seven or eight years that I’m doing the stories that are intertwined and connected to my personal work, about families, and people in sensitive or painful or crisis situations. It happens both naturally and also because this is what I love to do, and this is what I’m good at. My attempt at doing fashion work was not so good. All of us, you have to do find out what you want to do, and what your talent is. I admire all of it, fashion photographers, beauty photographers. It’s not necessarily…I don’t think I can do it well. Unless there is a very personal, intimate story there, a real mother and daughter and they happen to wear Dolce & Gabbana! Then I can relate to it! But I don’t have a good sense of style myself, and I don’t care so much about what people wear. I always remember the faces. So it was also trying to do things, not loving it, not doing them very successfully. And there are such talented people, especially here in New York, that will do it better than me, that it kind of happened organically, that I found my way to doing what I’m good at. Especially in such a competitive place like New York. If you’re not very good at something, there are millions of other people who can do it better. So I did my “real people” niche, that I’m very good at. Because I love people as they are. I don’t want to make them anything else, and I’m interested in who they are and what they feel. Which is terrible for fashion, but good for other stories!

Right! So I was looking through some other, some more recent photos for the New York Times and NYT Magazine, and there’s a lot of painful stories that they’re asking you to….

Right, now when I get an assignment and I call my husband to tell him I got a shoot, and he says, “What terrible thing happened?” Yeah it’s true.

How do you deal with that as you’re shooting?

I think the best and worst of us is always coming in crisis situations. And I’m just myself; it’s the same as I shoot my personal work, but different because I will not probably go as deep. I don’t love the people I photograph, but I do in a way for the day that I shoot. I come with a lot of, I don’t want to be corner, but I come with a lot of openness and love and respect and sensitivity to everybody, what people have been through. I respect the fact that they have let me in to take pictures. I usually share many of those pictures with them, and I just come as I am. As a mom, a daughter who’s photographed her whole family for thirty years. As an ex-belly dancer. You come to someone’s life with respect and sensitivity and openness, and try to also bring your photographer-self to work with light, but at the same time my focus is on the people.

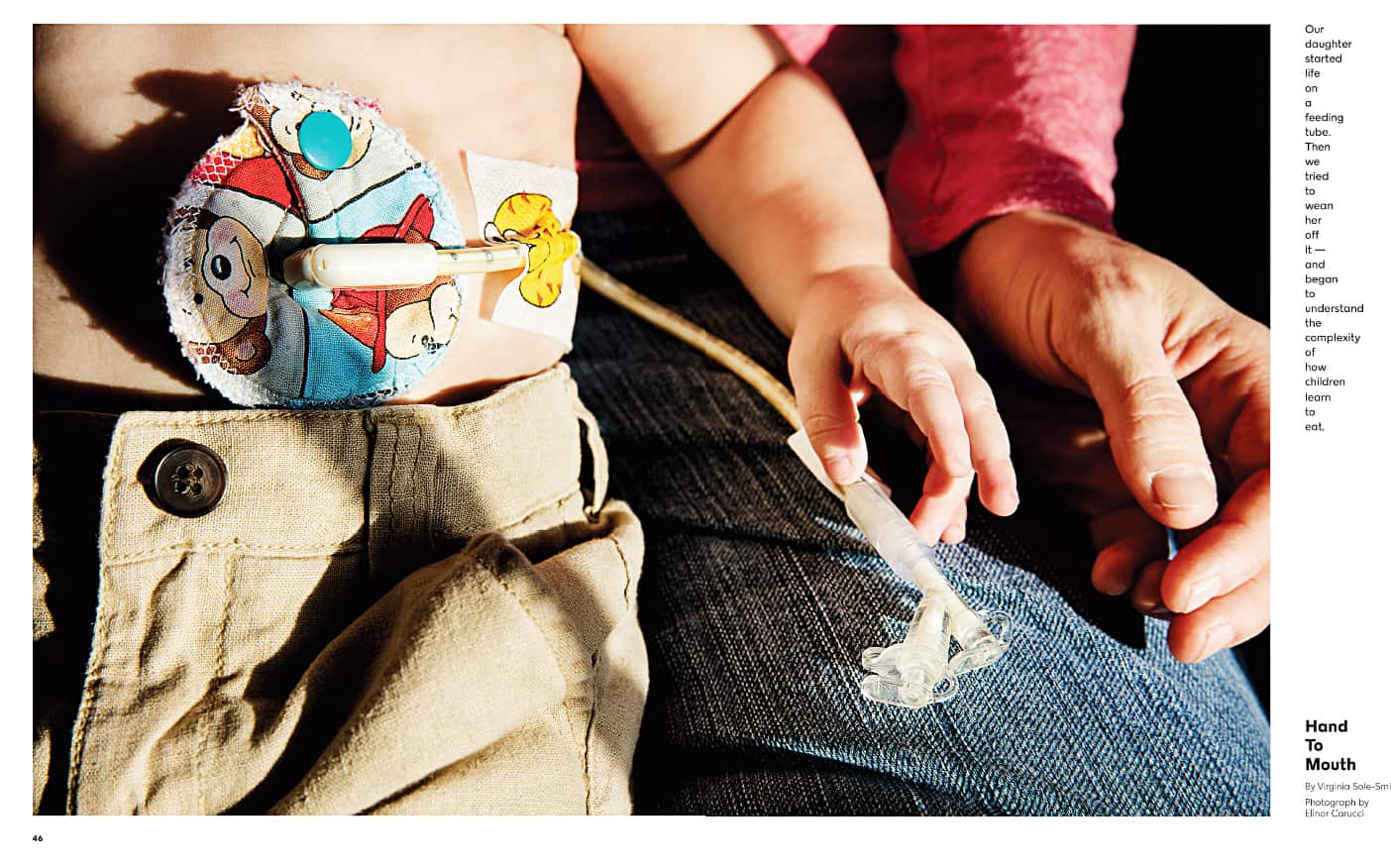

Various Selections from Elinor Carucci's Editorial Work

We talked to a few photojournalists last year, and something we should have asked them is, when you’re in these very emotional situations how do you protect yourself, emotionally? Do you?

Yeah, that’s….I guess it doesn’t necessarily matter if you photograph something or not. I have always been a sensitive person, and life is just…it’s waking up in the morning and knowing that we are all going to die. Terrible things are happening. If I photograph it or not, it doesn’t necessarily matter in terms of who I am. But I get very sad sometimes, and many times during the photoshoot, it’s not about me and my pain, it’s about the people. But when I’m editing it’s with tears and with tissues next to me because I can let myself cry. I’m not going to cry in a photoshoot.

Some of the things you photograph…I would cry in the middle of a photoshoot. They’re these deeply emotional events. I couldn’t do it.

I did a few times, but I really try not to because it shifts the focus to me and my pain. I try to be very gentle but to function, and to be very compassionate, but I need to be there for them and to take the pictures. But yes it has an effect. On the other hand, it does connect you to life in a way, and to what’s important, and what terrible and beautiful things are happening in the world. So it has a positive and painful effect.

How do you deal with that? So you give the photos to the families, that helps. Are there other ways in which you kind of…when I talked to Ron Haviv, he said there were things that he did when he came back to kind of put the conflict stuff in its place.

He was doing war, right?

War and conflict…

It’s more dramatic, I feel!

Well sure, but you’re still dealing with every emotional things.

I think a lot of it is happening in the encounter with the people. I spend a day or two with them; it is different because usually I’m not there. The thing that is painful is not happening in front of my eyes.

Ah, I see.

War is different. It’s very different from my kind of stories, and I admire war photographers. Don McCullin is…I think my most favorite image of all time is one of his images.But I photograph…I have a scheduled time, usually in the shelter or comfort of someone’s home. Where things are more therapeutic, anyway. In war, you’re not invited by the people who are there. There is a lot of collaboration when I’m there, and it is very healing, with those families; they give me the day from 10-6, and I’m there maybe two days. While in war you’re photographing as they happens. I might come back a year later to a situation that Ron photographed. So there is something therapeutic and comforting about the encounter with the people, that I find really beautiful. In terms of me, after the shoot I come back to my own family and look at the pictures, and those assignments sometimes affect my own work. Definitely it’s all connected, my personal work and those stories.

How do you think it has affected your personal work?

It’s very hard to know, you are exposed to someone’s life and to who they are and their emotions and their relationships, and it likely changes you. In a way, everyday in your life. Sometimes I go to the subway and you see something there and it changes you, whether you photographed it or not.

Are there things that, because you said earlier that the belly dancing series was not as well-received as your other work, are there other places you wanted to go that you didn’t because of how certain work was received?

You mean, photographically?

Yeah.

No, it’s not like what I photograph is very trendy right now. Anyway I’m not doing what’s trendy, I’m doing what I love. It’s also a combination of shooting for magazines and teaching and giving lectures, so it’s not like I have to sell a certain amount. It’s very, in all honesty, it’s very pure. I really do the work I believe in. I don’t have any kind of pressure because of how I built my career and how I make a living. So no.

Selections from Comfort – Elinor Carucci

It occurs to me because I can see your bookshelf behind you, what’s your favorite photo book?

I think, after all, I will have to say The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (by Nan Goldin). I was just at the ICP opening yesterday, and there was one photograph by Nan Goldin and for so many reasons, the quality of her work and the emotions of her work, it’s so alive and so, I feel, out of trend. It will always be important. It really guided me as a young photographer. How she broke all the rules to create something that by all rules is amazing. Work that is very honest and beautiful and complex and human. So it’s one of the books…as a photo student I looked at the book and I still have it and I still look at it. And I still get very moved when I see this work.

When did you discover for yourself that it has to be more than just “real”? That the quality of the shot matters.

You look at other photographer’s work. I remember seeing the work of Mary Ellen Mark, I was really young; she was maybe the first photographer that really moved me. Falkland Road, the book that she made in India, and I saw everything that I love about photography: the honesty, the emotion, the realness, and also the composition and the light, the colors. And some other elements that are also magical in photography that we can’t explain. So we see it in other people’s work, and they you make work, and you see all of the mediocre images that you are making. You understand that it’s very difficult to create work that is not only honest and emotional, but also you have to create a great image aesthetically, in terms of composition and light, the magic and drama, the whatever non-logical elements there are there. And you just learn it the hard way. You see how difficult it is, even when I was taking this after-school class when I was seventeen. Just as soon as you start showing your work, even to yourself, you see that it’s not enough, so you just learn it. You open your eyes and you understand the harsh reality of how hard it is to create a great image, not to mention a series of great images or a group. It’s very difficult.

Do you see that in your students? Do you see people come in, not understanding that aspect?

Yeah, but the ones that do understand it quickly, because it’s not too complex. We can, all of us, can sing in the shower with all of our hearts, but we’re not Beyonce. As we can all write in our journals but we’re not all Amos Oz. We all do things, but in order to make them, to bring them to an art/craft level, there are other things that need to be there other than our honest emotions.

How do you think a formal education helped you?

Oh, tremendously. Tremendously. I can trace back everything I’m doing today to my four years at Bezalel Academy of Art & Design, to the teachers, to the exposure to…first of all the dedication of “this is all you do.” And you’re not even thinking about how to sell the work, or how to get jobs, just the quality of your work for four years. And you learn about other photographers, and you see the process that other students are going through. And the connection, the relationship with the professors, it’s very very helpful. I don’t think it’s possible, even today with the internet, even though we can access so much information and images, going to school and having the critiques, especially in Israel, they kill that stage. Just having your work out there every week, every week and getting critiques and being beaten up, it’s very helpful. It really pushes you, as well.

Selections from Closer – Elinor Carucci

And my last question, we ask this of al our subjects. Which do you prefer: the process or the result?

It’s all connected. I don’t know. The process is so long. The process starts with seeing things and feeling and thinking about what you want to say. And looking at other pictures, then taking the camera and taking the picture and looking at them and editing. Then for me making the final files. It’s a long process. I really became good in Photoshop. Then putting it up on the wall. So the process is long, but I guess there is something very very primal, is that the right word? Very pure and basic in taking pictures. Because when I’m taking the pictures it’s almost like I’m not…and mainly I feel it when I’m dancing, and many other artists feel it, and it’s sometimes portrayed in movies, very badly. But there is a kind of focus that is very intense, your whole existence is about one thing, and this only happens when you take the pictures. When you edit them, when you print them, it is a part of the process, but when you take the picture there is something very intense and very pure and very focused, that maybe there is the magic of it all.

And that’s your favorite part?

It also has some stress to it, sometimes, especially when I’m on assignment. So it’s not a favorite, sometimes it much more creative, even when I’m working on the file, there’s something urgent, even in my personal work. I don’t know if it’s my favorite part, but it’s the most meaningful part, and it’s what keeps me alive. There is some adrenaline involved and there is something almost urgent about getting the picture. You are very very focused. And your whole existence is turned to one thing. I don’t know if to call it favorite but it’s THE thing.

Have you heard of flow? Or the runner’s high?

Right, it’s definitely this and I did feel it as a dancer as well. That’s why, when I say I love the people when I photograph or dance for them, of course I don’t mean Love in the same way I love and I’m committed to my husband or children or parents, but there is this state of mind in opening yourself up to the world. People call it vulnerability, but it’s not vulnerability because it does have some strength to it. And maybe in that way, it is similar. And when you dance, when you run, when you photograph people, there is something…I can come to a photoshoot, I can meet the family and I’m Elinor, I’m a good person, I’m compassionate, but as soon as I take the camera I see and feel and connect so much more. There is definitely a Before & After I get in the state of mind. And maybe it is what you are talking about with runners. There is a certain existence.

It happens in surfing and it happens when you’re conscious brain downshifts. And your more animal brain takes over.

That’s primal! That’s why I said primal.

Awesome, and I think that does it!

Thank you very much!

Thank you!