Interview 093 • Dec 9th 2024

- Interview by Chris Buck and Dan Gerdes, portraits of Bud Endress by Chris Buck

About Bud Endress

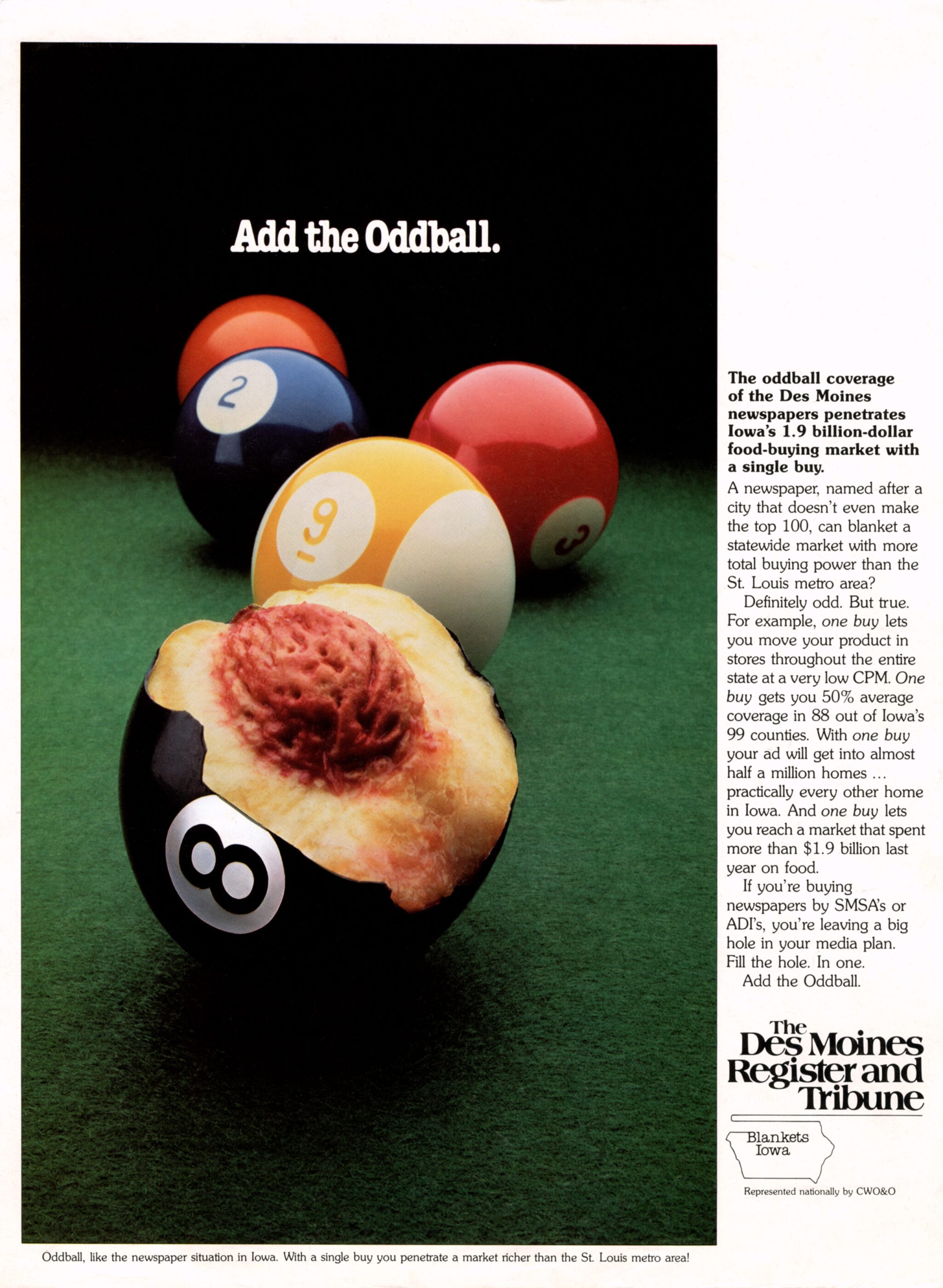

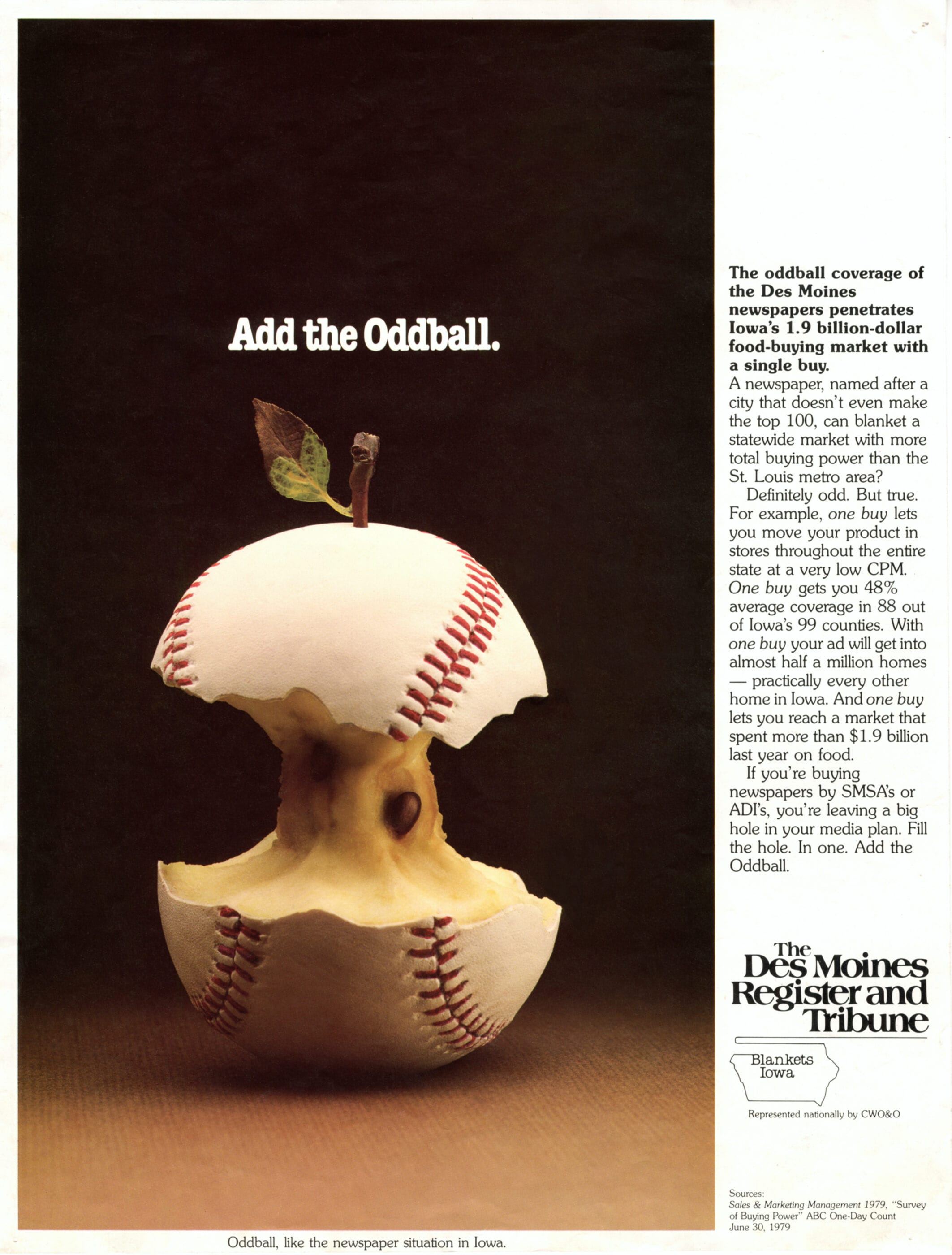

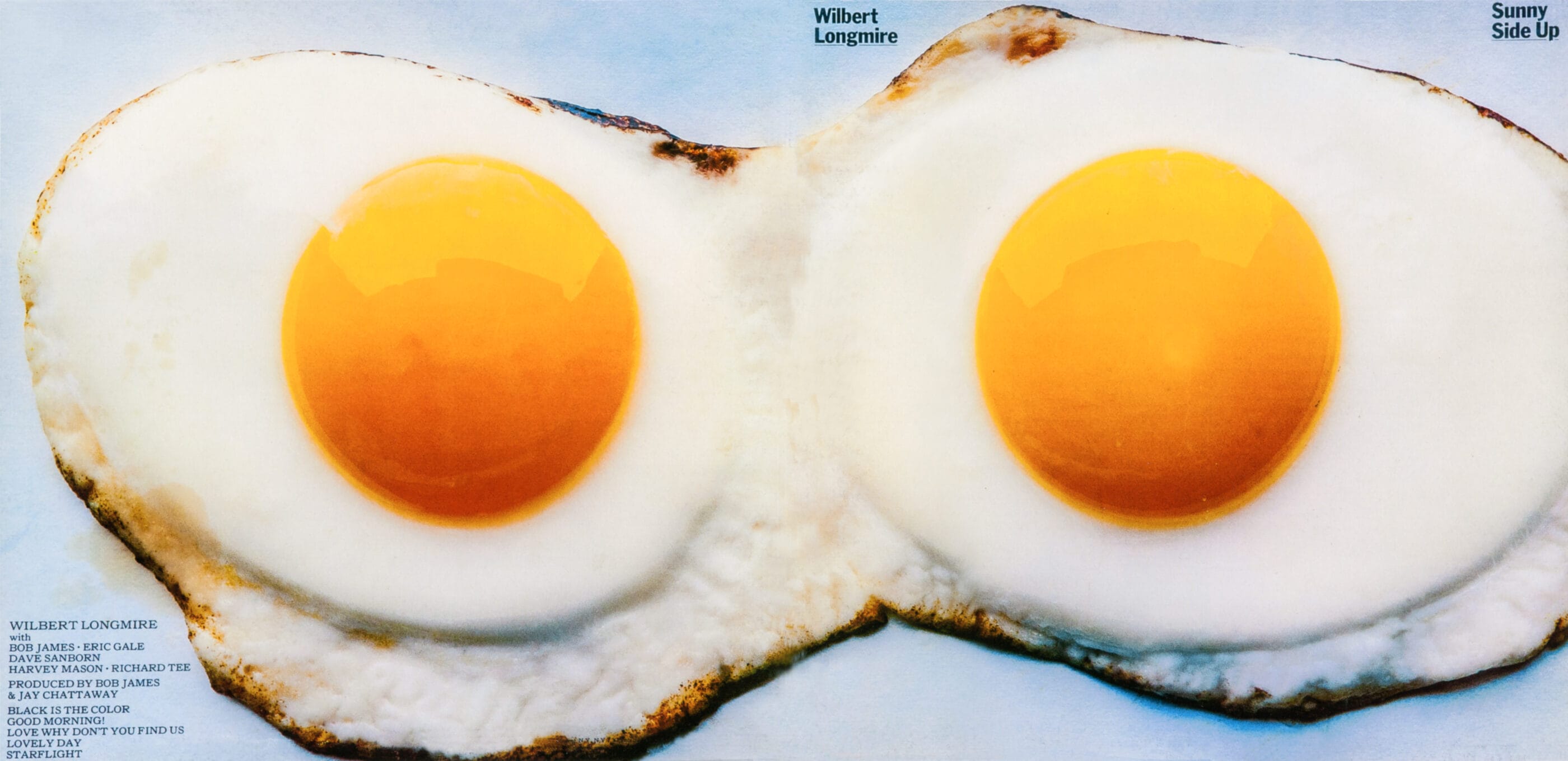

John Paul "Bud" Endress is a commercial studio photographer for over 40 years. Specializing in automobiles, airplanes, special effects, food, editorial & still-life.

Links

Foreword

John Paul "Bud" Endress was a photographer in New York in its commercial heyday from the mid-sixties to the mid-nineties. He specialized in precise still lifes, starting with food and beverage, and soon expanded to photographing cars and even fighter jets.

Thanks to advances in color separation technology, advertising had gone from being a largely illustration-based medium to one that increasingly relied upon photography. Suddenly, advertising needed photographers, and there was a lot of work.

Bud is a great storyteller, with no patience for pretense. And you might hear a profanity or two cross his lips, for emphasis. What I admire most about Bud is his raw honesty – his ability to be both unapologetically candid and fearlessly vulnerable. He understands that his greatest weakness is his greatest strength - his unvarnished authenticity.

----

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

Where does your connection to photography begin?

I learned about an art school in Newark; a four-story brick building that was meant to be like the Art Students League in New York. When I applied, the minute I said I was in the Navy and had the GI Bill, they loved me because they knew that they were gonna get paid.

What was it like going directly from the Navy to art school…in 1957, no less?

The first class I went to – the teacher had gone to the Bauhaus. He was German, which was pretty far out. I didn’t have any idea what the hell was going on at that point.

He said, “The first assignment is to buy a sixteen by twenty-inch piece of white illustration board and a roll of half-inch black tape and go all the way to the left edge of the whiteboard and put a half inch strip of tape. Leave a half inch of white, put another one, and do that across the whole board so you have a lot of vertical lines.”

And then he said, “Take an X-ACTO knife and cut out a piece of the black and move it into the white, and make a palm tree that, when you look at it, looks three-dimensional.”

So, I did it. Only, what I did was just put a bunch of stripes down and cut a half inch of black and move it in, so it looked like a damn checkerboard.

The next week when I went to class, all the other students had done it. And when I saw what they did with that tree, how they made it bigger, obviously, as it came to the bottom – it blew me away, and it just – I was totally enchanted by what had happened.

That started all my work in art – and I went there mainly because I didn’t wanna work.

Art school was your idea of avoiding work, yet ironically, that’s where you learned the skills that led to a successful career. Was that where you were first introduced to photography?

I was required to take a photography class in the third year, and I didn’t have any money to buy a camera, so I cut the class. The illustration teacher came and said to me, ” If you don’t go to this class, you’re not going to graduate.” So, the next week, I went, and I bought a camera for fifty dollars.

I took my girlfriend Ruth to her house, sat her in a chair, took the lampshade off a lamp, and put it on one side of her face.

It was five stops overexposed so the light side was pure white except for where the eye was. You could see the eye in the white, and the other side was pure black. I made a print of that; it was like an abstraction and I loved it.

Did you know then that you would pursue photography professionally after graduating?

One of the instructors was married to Irving Penn’s studio manager, a guy named Robert Freson. I went and I talked to him – he was extremely nice, and he said to me, “Your pictures look like you’re a student, but it’s okay. My suggestion to you would be to take an egg and take a picture of it.” And I tried to do it, but I had no idea what the hell I was doing.

At the time, I was working with my father, delivering cars from Linden where they made the General Motors vehicles. And I was washing trucks one day when my father phoned, “Some guy, ‘Irving’ called you. Call this number.” I rang Freson, and he said, “Would it be possible for you to come to work for us for two weeks?” I said, “Absolutely.” “Meet me tomorrow morning on 29th Street and First Avenue,” he said.

I walked in to see the shop steward and I said, “I quit.” He said, “Were you going to give me two weeks’ notice?” I said, “No, I’m leaving this minute.”

And just like that, you were off to work for Irving Penn.

I didn’t know anything about New York. The next day, I went out to 8th Avenue in front of Port Authority with the address to go to, and I see all these people jumping in cabs. A cab came up. A couple jumped in, and I joined them.

Now, the cab’s going uptown, but I’m heading downtown. The girl I’m sitting next to says to me, “Where are you going?” I said, “I’m going to 29th Street and First Avenue,” and she says, “You’re in the wrong cab. You’re going uptown.” I got out and got into another taxi.

When I arrive at Penn’s studio, they were shooting an ad for Singer with a sewing machine made eight foot high. A beautiful woman is standing in a beautiful gown in front of it.

I didn’t really do much, all I did was file negatives, clean the floor, and stuff like that.

But I gotta tell you, the next day, he’s shooting this woman in a bright red gown to her ankles and this incredibly beautiful white hairy cat sitting on her lap, and the background was a big piece of fabric. Irving Penn had this very old strobe – they were called Ascors. These 800-watt packs were loud. He set it up with one head that you could put an unbelievable amount of power through called a “sun” head.

He says to her, “Slide your butt back and sit up straighter. Okay. Turn up now. Lower your head a little bit.” And all of a sudden, he squeezes the shutter – boom! The cat disappears. And everybody’s like, “Where the hell did the cat go?!” You look up six feet – the cat is hanging onto the cloth background!

I know you wound up working with Arnold Newman at some point. Was that directly after working for Irving Penn?

In those days, telephone calls were 10¢. I would take the bus to Port Authority, go to the same wooden phone booth, which had a shelf on the side with yellow pages, and I turned to commercial photographers. I started at “A”, and I would make ten calls a day. Eventually, I got to Arnold Newman. I called, and I said, “I’m a young photographer, and I’m looking for a job.” He said, “Well, I happen to be hiring, why don’t you come up and see me.”

I got to his studio, he sat me down in his office and he said, “Tell me about yourself.” I said, “I went to art school.” He said, “Well, who have you worked for?” When I said, “Irving Penn” he put the note card down, asked me a couple more questions, and he asked, “Can you start Monday?”

He only paid me $90 a week, but I was with him for almost two years. After three months, he and I got on a train and went to Washington D.C. and photographed JFK by the front driveway of the White House.

One time, he was going all over Europe to photograph the Rothschilds – big wine people. He writes this whole list out for me telling me where I could send him the equipment, with what equipment he wanted. Right? I have the list and I get to a Western Union about “Send ‘Group B’ with two extra rolls of film.” So, I pack it up and I ship it to Israel.

The next day, I pick his wife up at the airport and she says, “Everything get off to Arnold?” I said, “Yeah, it went fine. It should be in Israel in the morning.” And she says, “What do you mean Israel? He’s in England!”

How long after that until you went into partnership with Bill Stettner?

I was working for Jerry Schatzberg and one day, as I was cleaning up, Bill Stettner knocked on the door. He said, “I was just upstairs looking for a job. The guy looked at our portfolio and said, “Why the hell are you looking for an assistant job when your portfolio is better than mine?”

We sat down, and he said, “We gotta go into business. I guarantee you that you will make enough money to feed and take care of your family.”

Bill’s father was a photographer who died young, his mother hired photographers to continue to shoot and she had this small space on 46th Street. She was ready to leave the business, so we paid her $75 a week to answer the phone.

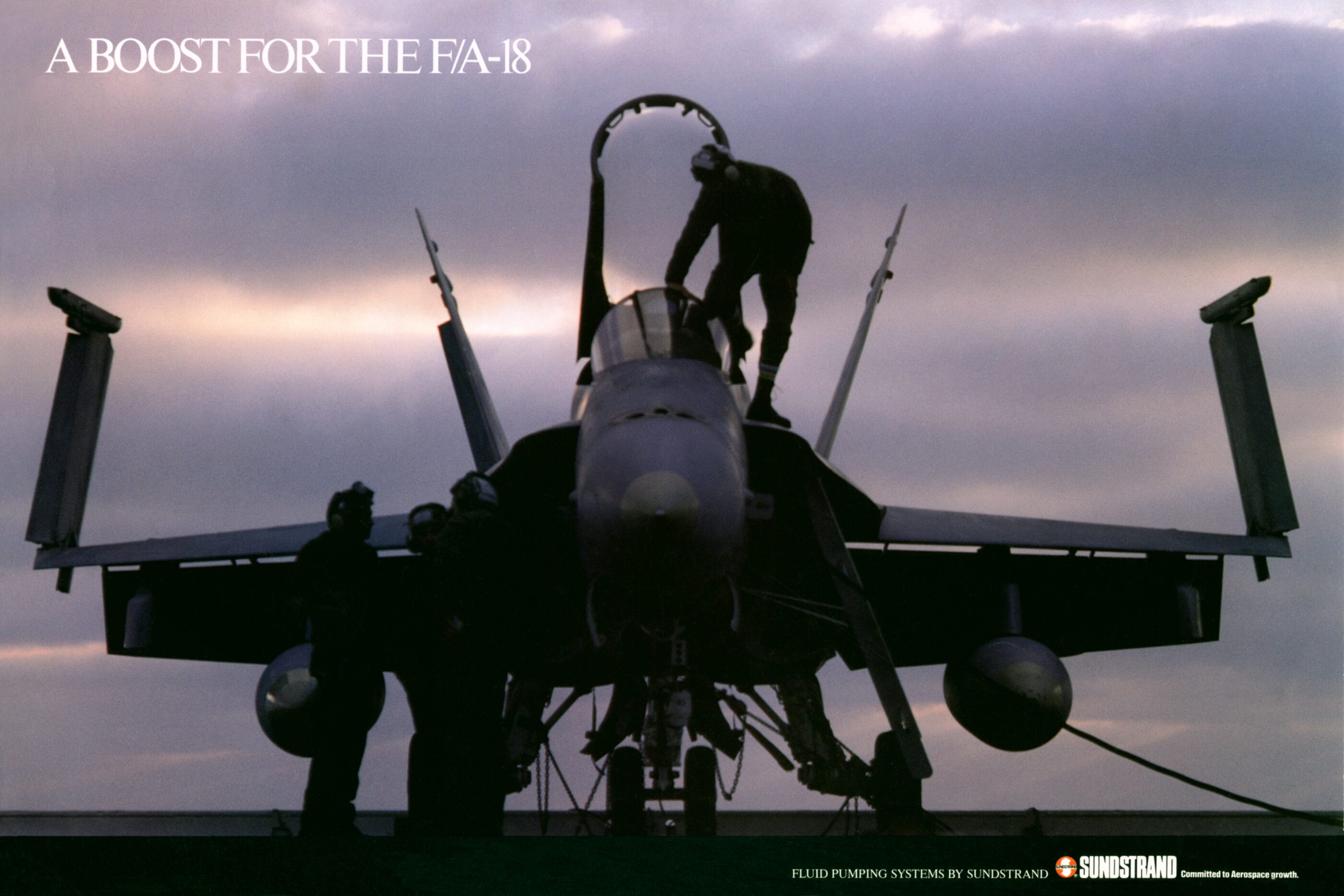

We shot this in the early morning on an aircraft carrier. The sun was lined up perfectly behind the F-18 but as we begin to shoot the carrier started to move. I say to the officer, “Tell them that they can't turn the goddamn thing, the sun's out of the picture now.” He laughed his ass off, “Do you think that we’re not going to turn the boat because the lighting isn’t right for you?”

We started shooting again and then I saw this man going up there. This is fantastic, I thought! I asked, “Are you the pilot?” “No sir, I'm here to wash the windshield.”

You and Bill Stettner are partners at this point but didn’t have any clients. Did you just shoot samples and shop them around?

In the late forties and fifties, printers couldn’t separate film colors, so everything in magazines was done using illustration. But that was all changing when we went into business in 1964.

Suddenly, all the advertising agencies in the city wanted to use photography as opposed to paintings. There weren’t a lot of photographers in New York at the time, so we got all of these opportunities. I was very young, and I was a photo assistant for a long time, then all of a sudden, I had all of these chances to shoot. I didn’t even realize that I had that talent until then.

When did things start to pick up for you?

At that time, we got a job from Richard K. Manoff, who was making a pitch for Rodrigo Rum. We had a copy of the layout, shot it, gave it to them. They got the account, and we made a bunch of money!

Did you have any plan for how you were going to keep things going?

The phone rang one day, and it was Jerry Shatzberg’s rep, a guy named Stan Corey. “Do you have a rep?” he asked. “No.” And he said, “Well, why don’t we go to lunch? I’m looking for young talent.”

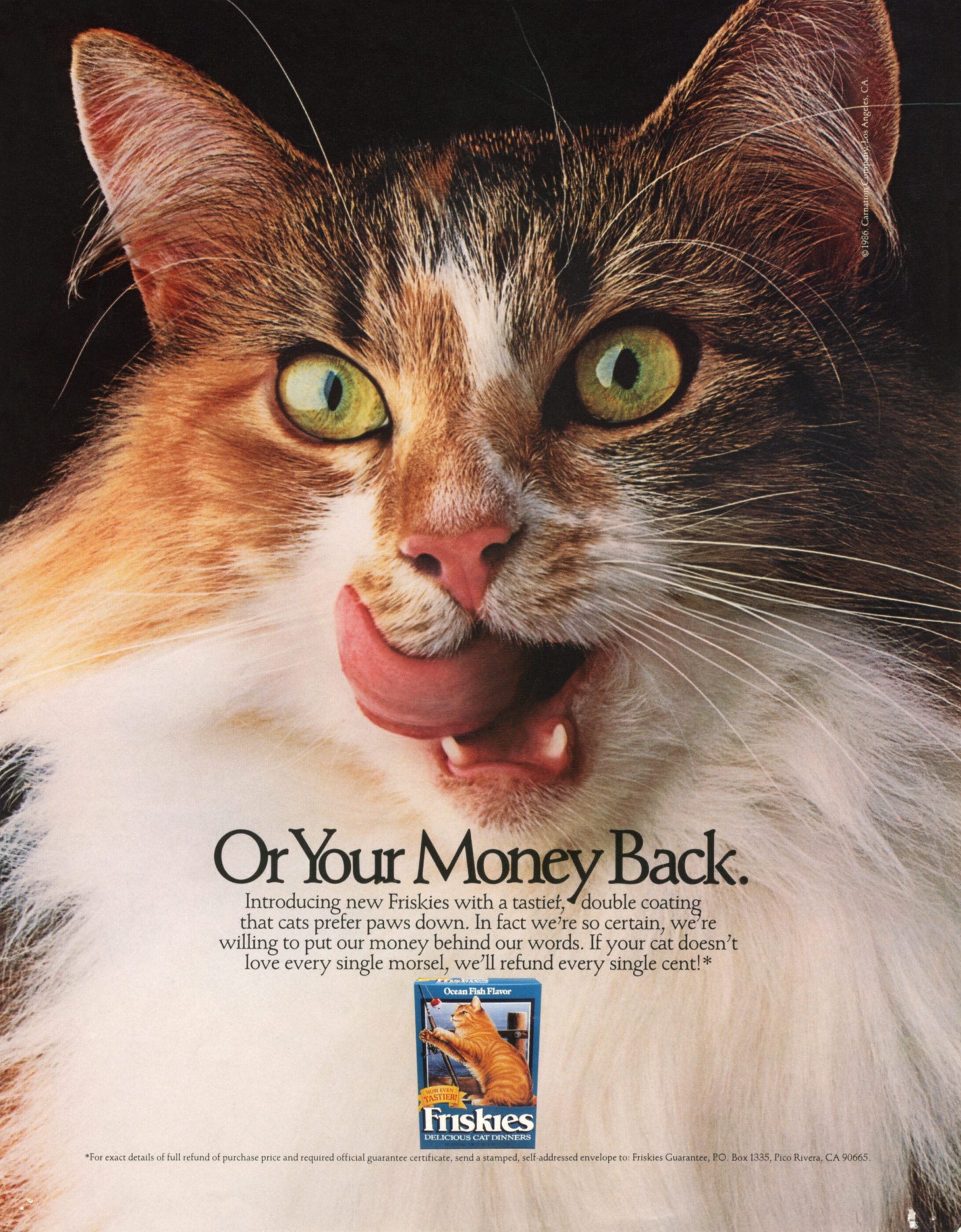

Everybody said, “Never in a million years can you get a cat do that!” I called the animal wrangler, and described the shot, and she said, “Okay.”

I watched her on set: she took her finger, dipped it in peanut butter, and scooped it into the roof of the cat’s mouth. The fucking cat sat there for 40 minutes licking it off!

We went to lunch and showed him our portfolio. So, a couple of weeks went by, and he walked in, and he said to me, “Alright. Listen. I got three days shooting for Coca-Cola. It’s $500 a day, all expenses paid, and we own the pictures. You’re going to shoot them. I’m gonna show them to them, and if they buy any, they’ll pay.”

We shot the whole job – shot a lot of film because they were paying, and about two or three weeks later, we get a check from McCann Erickson for $47,000.

We didn’t take a nickel. We got a new studio, bought Hasselblads, bought new Nikons. And we were really in business then.

How long were you and Bill partners for?

After six years, but in 1970, I told him I wanted to leave. I didn’t want to shoot food anymore as it was all shot from a 45º angle – everything.

That’s around the time that I met my next rep, Elaine Rubin. My billing went up to $180,000 the first year working with her – and it was more than that, most years.

What were you shooting once you were on your own?

I wanted to shoot cars, so when my lease was up, I decided I wanted a bigger space. I found a place on 31st Street – 6100 square feet, 18-foot ceilings, and a balcony with my office overlooking Penn Station. I had all that room, and I was making good money, so I put $30,000 into it. I put in two kitchens, built a cyclorama, and it was a ground floor studio. I made the front door six feet wider so I could fit any car in.

I imagine your overhead was pretty steep. How quickly were you able to get work shooting cars?

Around that time my rep Elaine left, and I called another guy that I knew, but he had too many people already. So, I said to him, “Do you know any young reps?” He told me about this guy – I can’t even remember his name, but I took him on, and he started to rep me.

Mercedes Benz had a magazine that, if you buy a car, you get a subscription to the magazine. And because I had shot some samples of cars, I got this job.

The guy who made the decision about who was going to work with him was a nut for focus. I called Marty Forscher, “I just bought this fucking lens here and it only stops down to f 22. He asked, “How many strobe packs do you have?” I said, “We have 16 packs, 2400-watt seconds.” A couple days later, the lens came back, stopped down to f 90.

I also had an overhead light bank that was 20 feet x 15 feet wide. It was a Chimera bank that had eight heads in there. I had my model maker rig the bank so I could lower this part or that part. The instructions from this focus guy was like, “Don’t shoot it from the back. I hate the back.”

The car arrived, and the first thing I did was shoot it from the back.

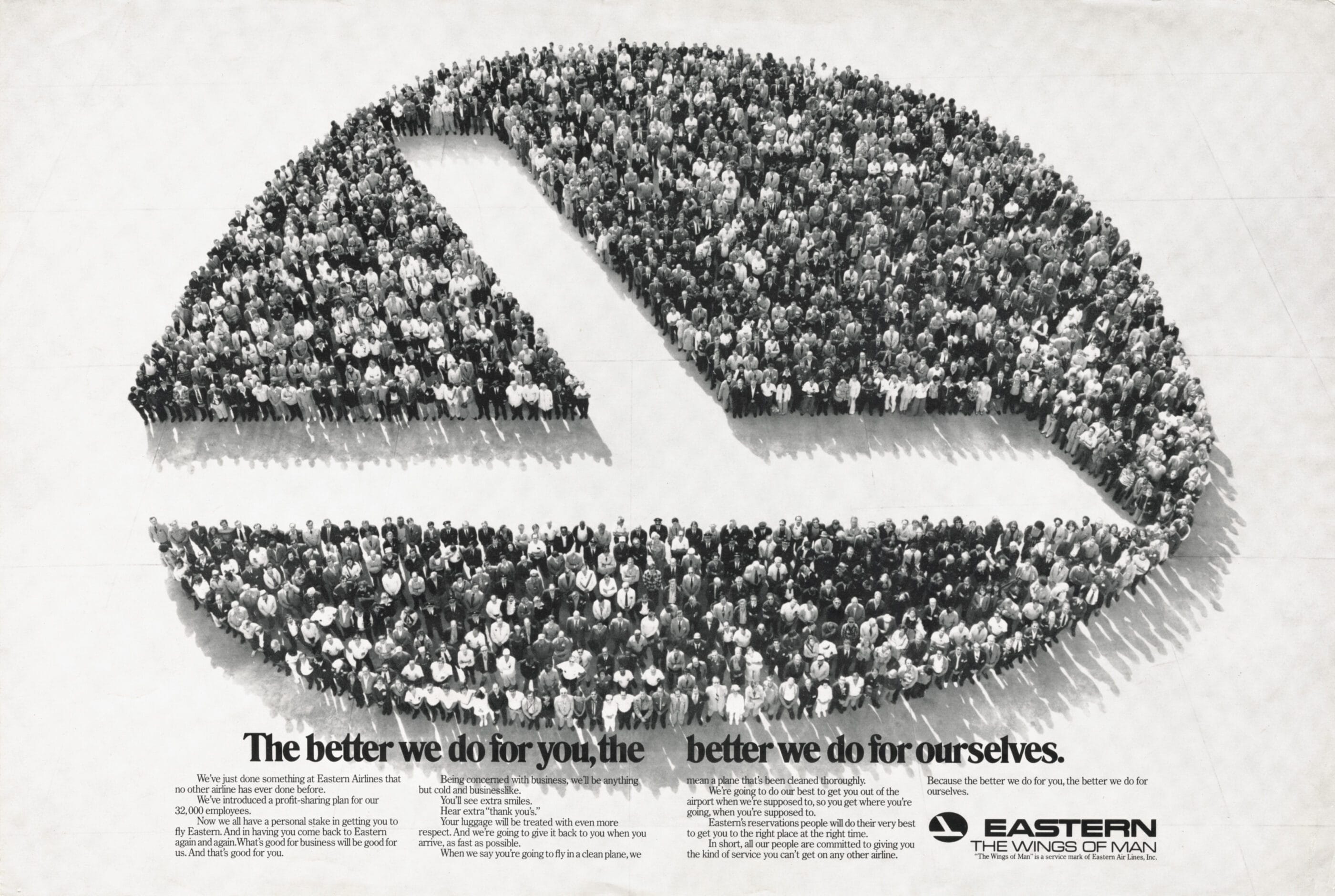

One of your most famously complicated shoots was a group photo for Eastern Airlines. It was an image of the company’s logo but composed entirely of the company’s employees.

All I got was a drawing when I got the job. “How the hell am I going to figure this out?” It was a lot of people. There was, like, a hundred of them. I was driving to the studio one morning and it popped into my head, “Square footage.”

The shoot was in Florida, so I called the band director at the University of Miami, and I explained to him what I was doing. I asked, “How many square feet do you leave for a guy in a band?” And he said, “A foot and a half.” He said, “What are you doing anyway?” I said, “Listen, I have a layout here, let me FedEx it to you and then you can look at it.”

When I got to the location in Miami, I went up 250 feet, to the top of the hangar, and there wasn’t an airplane in sight (the facility knew what was going on and left it totally wide open). I looked down on the hangar floor, and it was all made up of 25-foot squares. It looked like graph paper.

I called the band leader from up there, and he said, “Alright. I got it all figured out.” As he walked me through the specific dimensions, I wrote it all down.

But the logo is an ellipse, and I couldn’t do it – it was too big.

I went to a sailing store, and I bought $450 of soft rope. I went on top with the camera, with a copy of the layout on a piece of acetate. I was looking in the camera, and we talked through walkie talkies. I said to my assistant, “Keep the rope tight, and walk this way.” And he did, then the rope went to here, to here, to here, to here. [Gestures as if to indicate the oval outline in the layout.] Every time it would match the line on the acetate, I would say, “Tape it, tape it, tape it.” And we went around the whole thing.

So, we’re in there, and I had these prints that were really big, two of them on an easel. It was 100% exactly what the photo was going to be.

Then the day of the shooting – it was a Saturday – I had 2,000 copies of the layout done for each person; it was all there. As they’d come through the gate, everybody got one. We had fifty-five-gallon drums going up with rope on it, so they all had to get in from the back. They all came in, filled the whole thing.

I shot twenty-five sheets of black and white. All 8×10″. And twenty-five sheets of color.

What is the surprising part of being a good photographer? People know the obvious stuff, like composition, and the technical aspects, so what is the additional piece?

The technical shit don’t mean anything; especially today because the cameras are too smart.

Don’t ever get to be a fucking old man, that’s all I gotta say. I don’t know how the hell it happened. When I was shooting pictures, I just thought creatively. You know? And then I used to smoke grass almost every day.

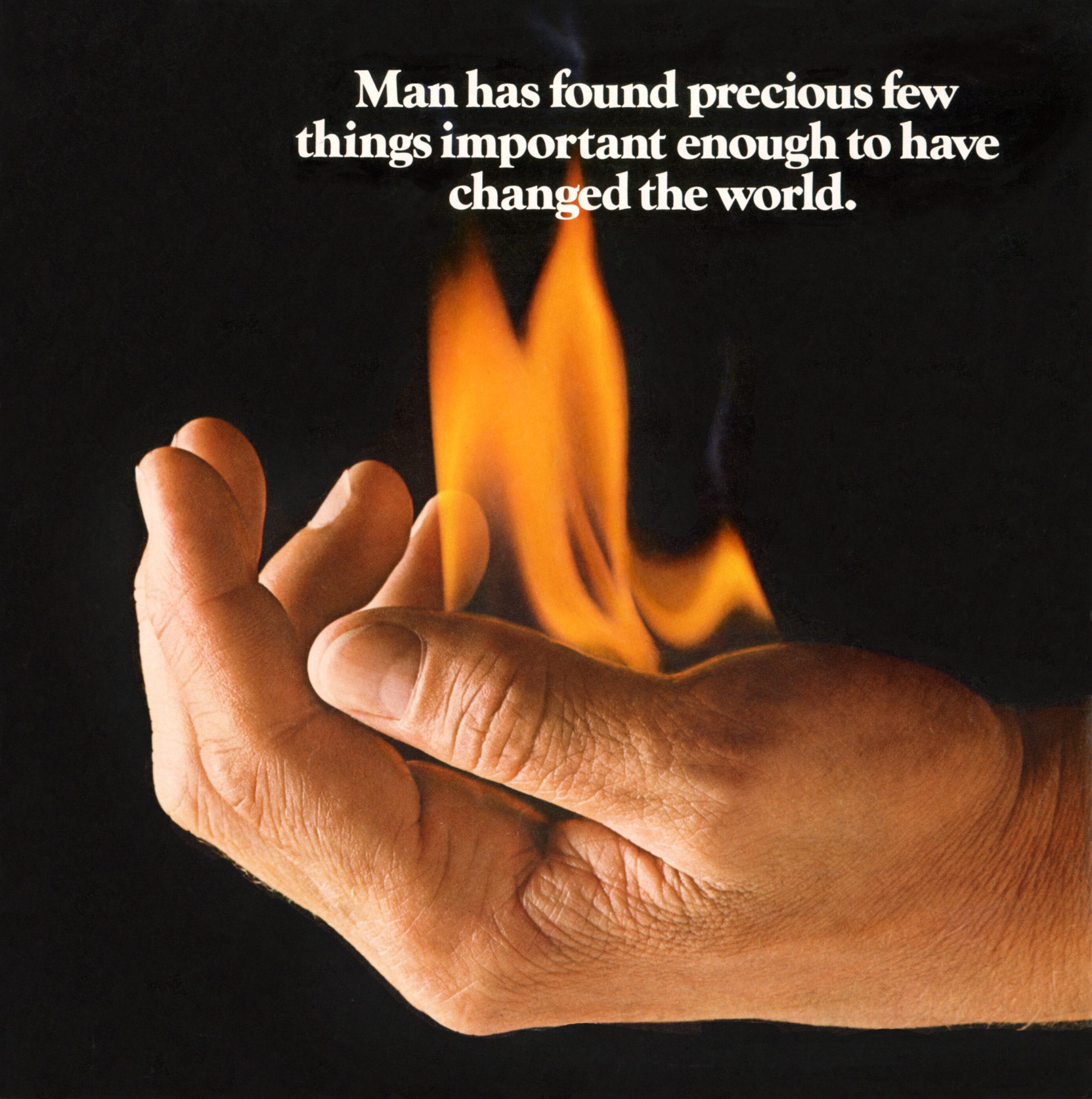

I booked a professional hand model, but once he was on set and saw the setup, he said, “I can't put fire in my hand - I'm a hand model!” He left and the art director stepped in. We poured lighter fluid into a bottle cap and tucked it into the middle of his hand. We shot a long exposure to mix the flame and the strobe-lit hand. It was 1/15th of a second exposure. Everything in one frame, with nothing Photoshopped.

One time an art director asked me, “What do you think about smoking grass every day?” I said, “You want the answer, the truth? It makes me smarter.” When I do a couple of hits on a joint my mind opens up. There is fucking no question about it.

And I’ll tell you something else, I am very lucky. My mother told me that I had a guardian angel. I quit school when I was 16. I was very fucked up because I couldn’t spell. I’m 89 now; I still can’t spell.

When I was young, in my mother’s house, there was a big mirror over the couch. Every Christmas I would paint Santa Claus and the reindeers on the mirror. And underneath it, I would write out “Merry Christmas.”

One year I took my girlfriend (and future wife) home to meet my parents for the holidays. We ate, and it was fun and nice. When we got in the car to drive her home, she said, “Can I ask you a question? Why did it say ‘Mary Chirpmes’ under the reindeers on the mirror?” I had written that; I couldn’t fucking spell, and my mother and father never said a fucking word.

Why did you close your New York studio? Were there changes happening in the nineties?

Everything broke loose! The cameras got way smarter – everybody could shoot anything. You didn’t have to know anything about lighting or anything. And the rates went way the fuck down. So, in 1994 I decided, fuck it, I’m going to close my studio. I had enough money to do shit.

I thought I’d never get assignments in New Jersey. It turned out that I got a lot of jobs, and I opened a studio in Caldwell, it was dynamite.

Alright, any final words?

I was telling my son J.P. the other day, “If I drop dead right now, you better come look at me, because I’m gonna be laying there with a big smile on my face.”