Feature 019 • Mar 23rd 2025

- Written and curated by Julia Gilban-Cohen and Ricki Blakesberg, with photos from the Retro Photo Archive

Presented in conjunction with the Retro Photo Archive!

Elizabeth Sunflower (1943-2008) was an esteemed photojournalist based in San Francisco, CA. Having an affinity for capturing local news events and alternative pop-culture trends, Sunflower established herself as a reliable, innovative artist – a reputation that extends outside the borders of San Francisco to the national stage.

Owned by Retro Photo Archive along with the remainder of her portfolio, Sunflower’s photographs of The Occupation of Alcatraz (1969-1971) mark only part of her prolific career.

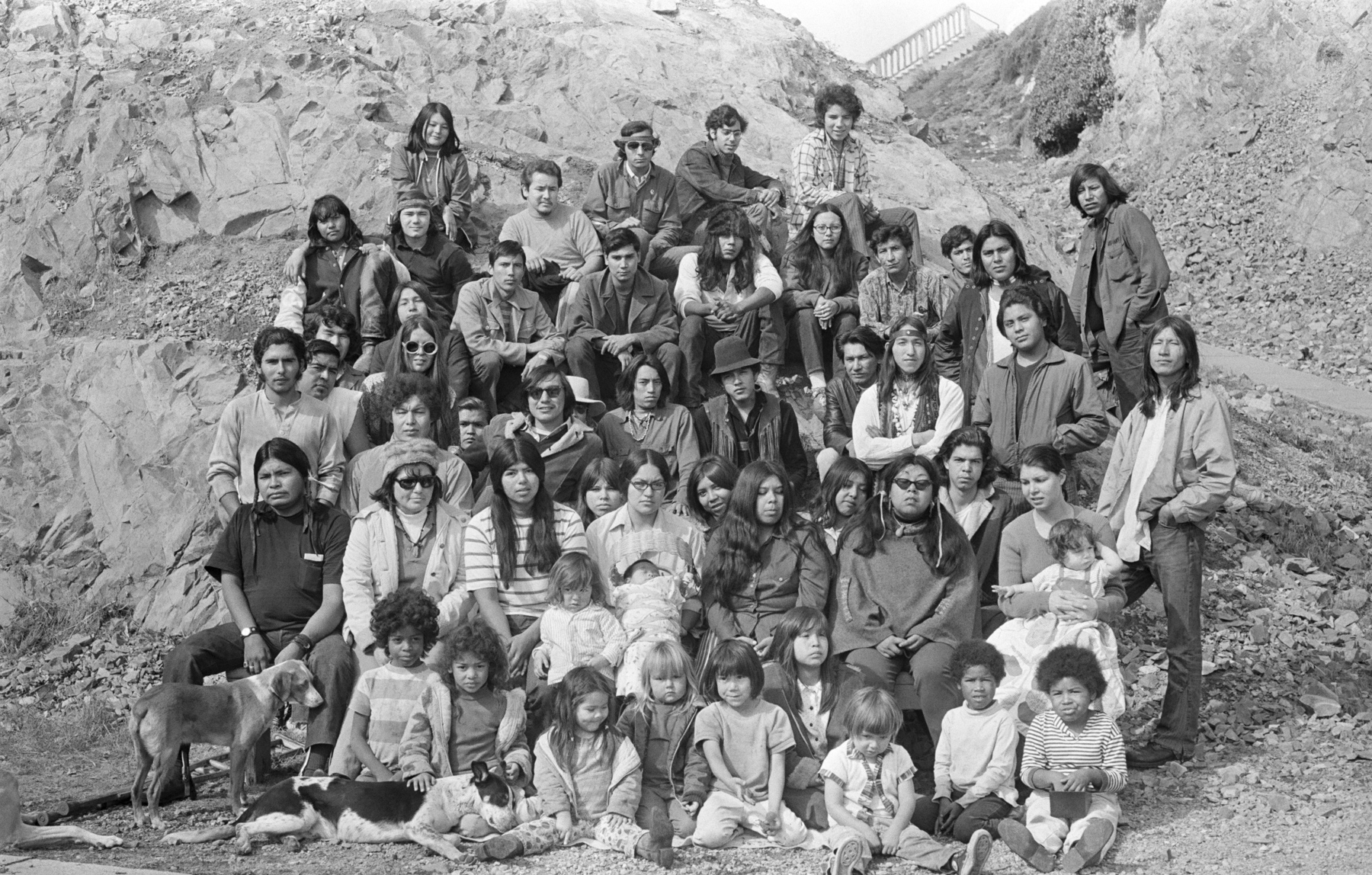

Elizabeth Sunflower documented the 1969-1971 occupation of Alcatraz Island, immortalizing an indigenous peoples’ movement to reclaim native land. The images in this collection capture the raw energy of Native Americans’ desire for self-determination and communal identity, expressing not only the movement’s urgency, but also the everyday humanity within it. Seemingly casual conversations, multi-generational music circles, subjects in native dress represent Sunflower’s attention to the day-to-day life of the island, immersing her audience into the passion, purpose and the fight of the moment. During the 19-month movement, daily life on the island brought joy, allyship, conflict, anger and resistance to the forefront – through her images, Sunflower transports viewers into the eyes of individuals fighting for what they believe to be rightly their own.

We Hold the Rock: A Budding Movement

Seemingly unbeknownst to even most San Franciscans, from November 1969 to June 1971, Native Americans took over and held the famous Alcatraz island as their own. Following the prison’s closure in 1963, the Native American activist group, Indians of all Tribes (IAT), led the occupation, igniting a movement for sovereignty and justice.

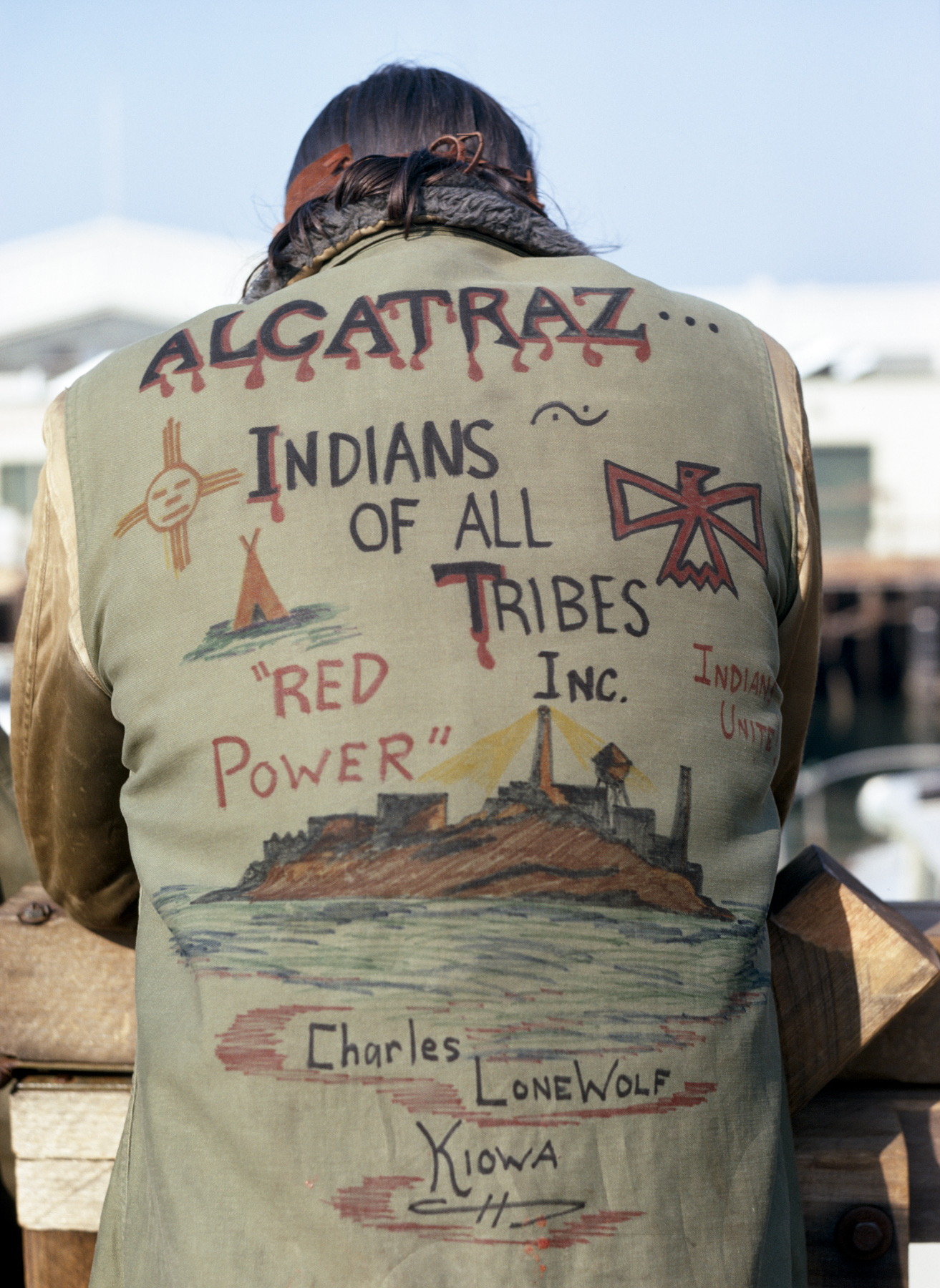

Initially an effort to raise awareness of the continued oppression facing Native American tribes throughout the country, the takeover eventually evolved into a proclamation to permanently take claim over the island. In this photo, the handwritten and illustrated vest points to the scrappiness of the movement, as participants relied on community support and their own resourcefulness; despite the challenges the disruptors faced in occupying the island, their collective belief in and desire for self-determination fueled their actions each day.

According to the U.S. National Park Service, just one month prior to IAT’s takeover of the famed island in June 1969, the San Francisco American Indian Center (AIC) burned down. Formerly located between San Francisco’s Mission and Valencia streets, the former locale was a physical representation of Native American community and political visibility – this tragedy played a significant role in IAT’s decision to occupy Alcatraz, in an effort to emulate the atmosphere of the center and its seemingly lost tenets. The back of the subject’s vest in this photo illuminates this effort, with the island drawn almost as if to be compared to an oasis surrounded by sea.

Red Power activists thus wanted their presence on Alcatraz to constitute more than just a peaceful protest – the occupants and their supporters, the latter of which included students, ally groups, celebrities and other local San Franciscans, hoped to conjure a reality where Alcatraz could serve as its own Native American community. Most importantly, and in line with the organizer’s namesake, IAT aimed to create a space where all Native Americans would have indisputable ownership of the 22-acre island.

Along with the subjects’ collective look out into the distance, Sunflower’s rare inclusion of color in this photo, in contrast to the rest of the largely black-and-white collection, appear to symbolize hope and ideation. Three individuals, presumably Native Americans, peer out on the horizon. Viewers can imagine the photo’s subjects looking at the vast bay, perhaps signifying cleansing and clarity, in addition to the major metropolitan city of San Francisco – a poignant representation of the evolution of tribal life in line with contemporary society – as beautiful, rather than threatening.

Moreover, the images contain an undeniable thread of voyeurism; there’s a sense that we, as outsiders, are being granted a privileged glimpse into an unfolding reality, a community in motion. This tension between immersion and detachment is what gives the work its complexity – it challenges us to think not only about what is happening within the frame but about our own relationship to it.

“It’s so easy when you’re fighting on the side of the marginalized when you’re fighting from a position of being among the oppressed to allow your anger, your frustration to turn into hate or even violence. They [the Alcatraz protesters] were unarmed. They were trying to really do something very, very positive. That’s definitely a legacy that I want to be a part of, a legacy I want to help leave behind.”

– Marc Charles, Native American activist, speaker, writer and dual citizen to the United States and Navajo Nation

Sunflower’s collection does not constitute mere documentation, but rather immerses viewers into lived experiences, each framing a testament to the fight, resilience and emotion that shaped the movement. Even in a moment of confrontation, like the interaction between policemen and a Native activist in the photograph above, hostility seems to take a backseat to something more nuanced. IAT’s commitment to nonviolence, as shown in the Native subject’s demeanor and stance, is heightened in contrast to the police officer’s confrontational body language.

Naturally, celebrities played a major role in popularizing the takeover from a local protest to a national movement. Actor Anthony Quinn, pictured in a fedora speaking to a Native activist, left, played Indigenous characters throughout his movie career. At the time, Quinn paused the filming of the movie Flap, to make a high-profile visit to the Alcatraz island takeover. In this photo, Sunflower astutely captures a conversation between Quinn and a Native activist, compelling viewers to wonder: what questions, if any, is he asking? What is Quinn seeking to learn from this activist? What did the activist share? Two peace signs are held between the arms of the activist, presumably made by a child sitting behind him, reminding viewers of the joy interwoven within the entire movement.

Mainly due to Quinn’s advocacy, Flap offered a sympathetic lens to the plight of Native Americans. According to KQED, promotion for the movie turned attention to the Alcatraz occupation, including posters that read: “A warning to the Mayor: Flap is here! The Indians have already claimed Alcatraz. City Hall may be next. You have been warned.”

In addition to his presence, Quinn contributed financially to the IAT’s takeover of Alcatraz and openly supported the takeover’s aims. He told a press conference: “Alcatraz is a small price for all the sins we committed and indignities we forced on the Indians.”

Among other well-known American figures, Buffy Sainte Marie also visited the island during its takeover and actively supported IAT’s movement for indigenous dignity and self-determination. Sainte Marie, a prominent singer-songwriter who was outspoken about the injustices facing indigenous people throughout her entire career, believed music could change perspectives.

Sainte Marie actively helped fund the Alcatraz takeover through her performances and shows. Her songs, “Universal Soldier”, “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone”, “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” and “My Country Tis of Thee” addressed the challenges facing indigenous people, expressing the rage and anguish from living under colonial oppression whilst conjuring a sense of duty and hope.

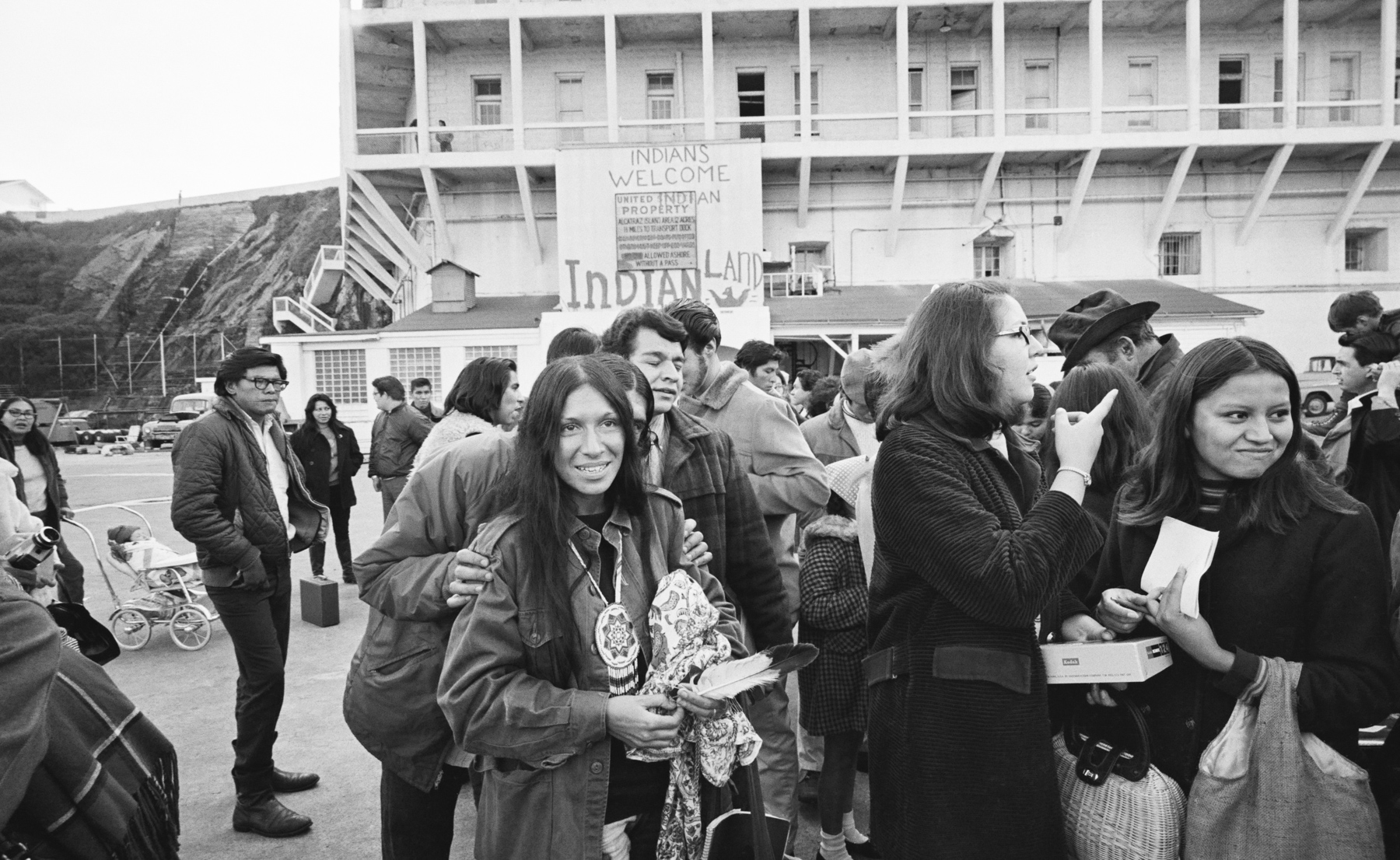

Pictured with long, middle-parted hair and native accessories, including a feather and beaded necklace, Sainte Marie is seen as an exuberant subject, eager to take part in all that surrounds her. Another subject stands behind her, perhaps speaking something into her ear, holding her just below the shoulders – the subjects’ body language, in addition to Sainte Marie’s brightly lit face and growing smile, captures the excitement of the moment and the brewing sense of positive change being near on the horizon.

What stands out most strikingly is the prevailing presence of joy. Perhaps these smiles speak to a deep inner confidence, a recognition that the fight itself is not just about reclaiming land but also about affirming life. In the above photograph, multi-generational subjects wistfully carry out tenets of tribal life, ushering in a younger generation – including non-Native Americans – to sacred practices, performed as a collective.

While resistance is often depicted through a lens of struggle and conflict, Sunflower’s audience is privy to an alternative reality – a narrative woven with smiles, laughter and undeniable moments of connection. Resistance, in this case, is not purely about defiance but rather the sheer will to exist freely and fully.

Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) and the Alcatraz Proclamation

19th century clashes between the U.S. government’s drive for expansion and Native American tribes’ desire to preserve their lands led to the Treaty of Laramie – an agreement made where the United States would “return all retired, abandoned and out of use federal lands” to the Sioux people.

In defense of their protest’s mission, Indians of All Tribes cited the 1868 treaty, claiming that Alcatraz had unequivocally become unused federal land. Activists also argued the island aptly resembled most reservations, namely in the sense that it is isolated from modern facilities and would allow for an independent society.

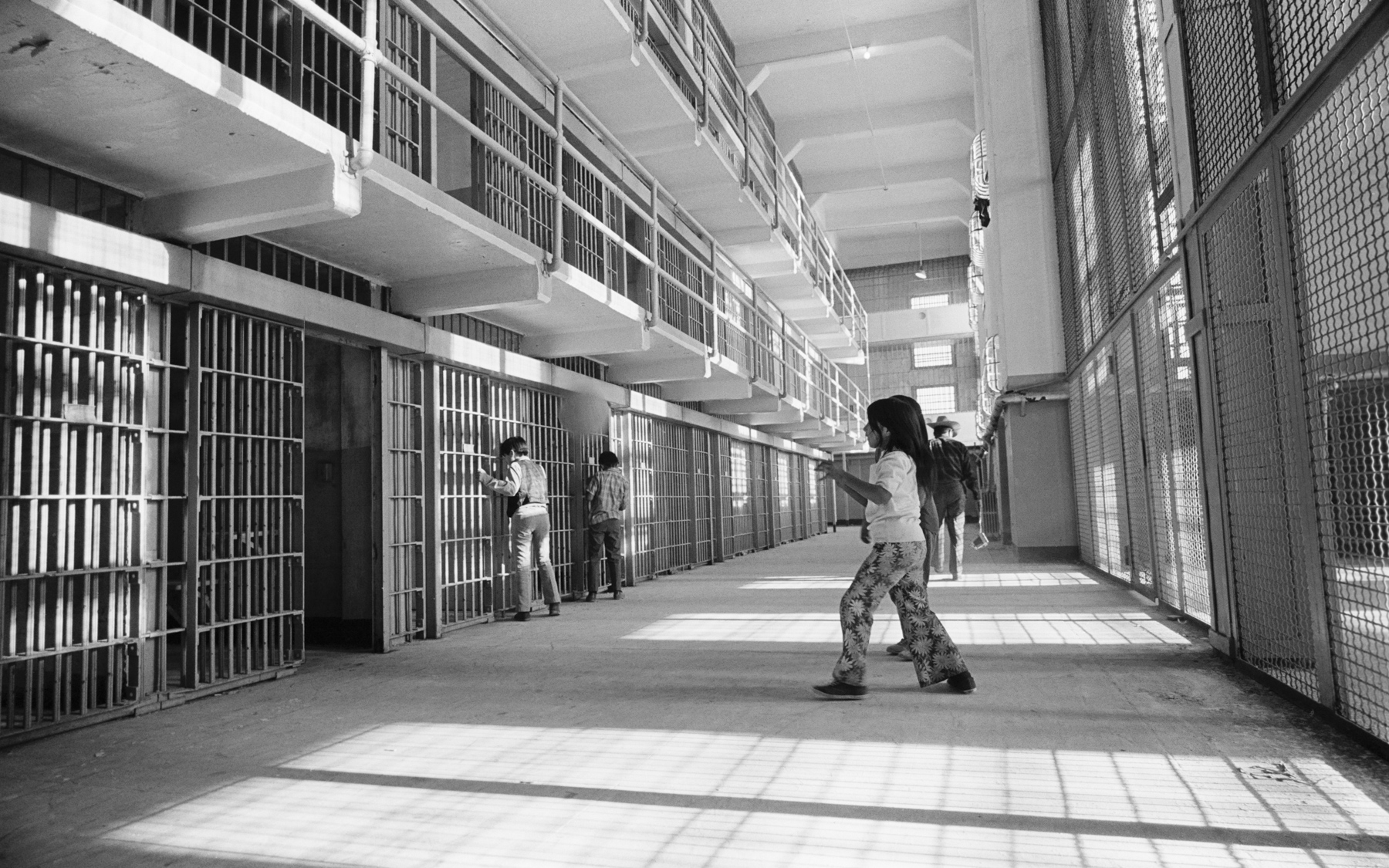

It’s difficult for viewers to ignore the irony of indigenous Americans taking over the infamous prison; an environment once used for detainment and control, a place to isolate harmful actors from society, being reclaimed by a historically marginalized demographic as a space for community, inclusion and tradition. The child in the above photograph encourages playfulness, despite the bleak backdrop of concrete floors and barred cages, highlighting the IAT’s inherent desire to recreate the locale’s narrative.

According to the protesters’ statements, especially since the destruction of the American Indian Center, there was no place for Native Americans to assemble and carry out tribal life within the confines of San Francisco. The above claims and more were developed into the Alcatraz Proclamation:

“It would be fitting and symbolic that ships from all over the world, entering the Golden Gate, would first see Indian land, and thus be reminded of the true history of this nation. This tiny island would be a symbol of the great lands once ruled by free and noble Indians […] “We feel this claim is just and proper, and that this land should rightfully be granted to us for as long as the rivers shall run and the sun shall shine.”

Indicative of allyship, a white man (below) in traditional Native dress holds the proclamation toward Sunflower’s lens. The subjects’ stoic expressions reveal a sobering declaration to retrieve what is believed to be rightfully their own. Not to mention, the choice of the activists to use animal hyde as a canvas for their proclamation emphasizes the desire to reclaim indigenous practices.

Throughout Sunflower’s collection, there is a pattern of educating – whether it be Anthony Quinn conversing with a native activist, older folks playing drums with youth or an activist in full Native dress speaking to a blonde female subject, likely a reporter, and handing her two feathers. These types of interactions Sunflower was able to capture emphasize the movement’s desire to teach, to call others in, and to envision a more just, beautiful world that promotes dignity for society’s most marginalized communities.

The occupation lasted a remarkable 19 months, until the city of San Francisco allegedly cut off basic resources, like water and electricity, to those living on the island. The 1960s ushered in a slew of civil rights movements within the U.S. and a global era of self-determination; Alcatraz’s occupation by several hundred Native Americans, community members and additional supporters served as a catalyst for the ongoing Red Power Movement.

The deliberate crossing out of “states” to put “Indian” in its place further promotes indigenous peoples’ collective identity – and the communal yearning for self-determination. Sunflower also captures the subjects, located on the top right of the photo, standing up high, almost looking down at anyone who may try to challenge their stance.

By declaring Alcatraz as Native land, the 19-month occupation echoed centuries of resilience, commitments to nonviolence and the belief in tribal life as sacred.