Feature 009 • Nov 22nd 2020

- Interviews by Joe Brennan, All Material Compiled by Joe Brennan

When Larry Kramer passed away in May of this year, the news arrived amid the second plague of his lifetime. At the age of 84, the poetic polemicist had already been mobilizing in his typical style, drafting up a play entitled An Army of Lovers Must Not Die in response to a new pandemic that was once again engulfing the everyday. It might have gone on to premiere some four decades after his essay “1,112 and Counting” helped light a thousand or so matches beneath AIDS activism in the pages of New York Native.

A humorist, a dramatist, a pamphleteer, a self-promoter, an angel, a pest, a Pulitzer finalist. As co-founder of both the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in 1982 and grassroots organization ACT UP in 1987, Kramer possessed a famously combative manner that courted the scorn of his compatriots and the admiration of his sworn enemies. Feted and rebuked in equal measure, he was master of the makeshift pulpit, his peerless oration known to form cathedrals out of curbsides and community halls. He was also a man of joy and bracing good humor.

Impossible to hem in and so often cast out, Kramer committed his life to matters of public health and moral outrage—on the stage and in the streets. His prolific fury, like his singularly expressive face, always preceded him. From bustling meeting rooms to the relative quiet of his Greenwich Village apartment, Kramer was accordingly one of the most frequently pictured figures of his movement.

Six months on from his death, seven photographers reflect on their portrait sessions with the late activist and tireless agitator.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

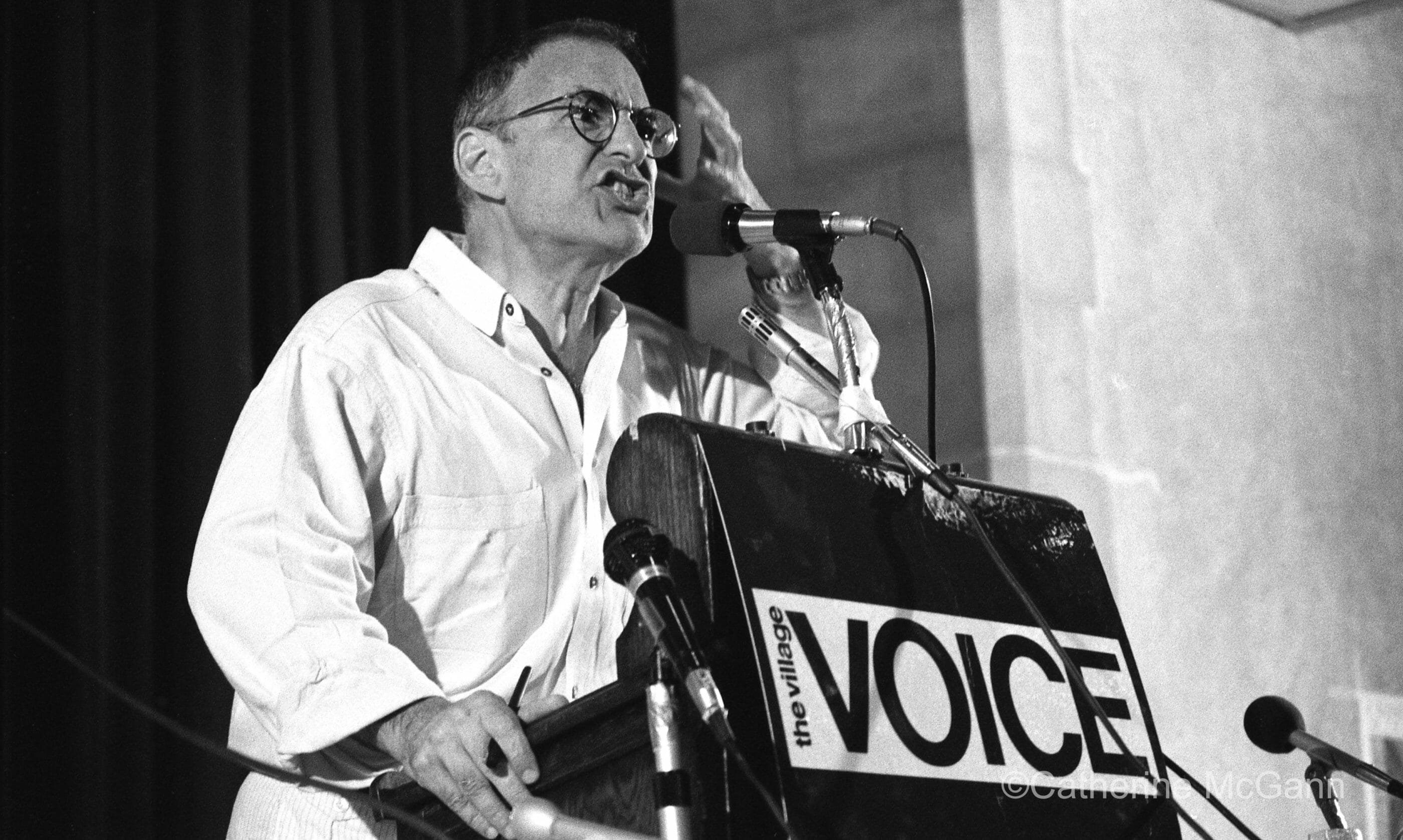

Catherine McGann, 1987 and 1993

At this point in my life, it’s been thirty or so years since I did a lot of these photography assignments but I’ve never forgotten Larry. He is someone that I carry with me. I was 22 or 23 and had only been at the Village Voice for a year when they hosted a conference on AIDS at some strange little community space in the East Village. Basically I was in the right place at the right time.

There was just a handful of people in the room—I can remember Richard Goldstein, Michael Callen and a few other well-known gay New York luminaries. When Larry got up and started yelling at everybody, he was riveting. He was shouting, “My friends are dying. You’re going to be dead if you don’t do something.” He just put everybody into their place and the whole room was stunned. It was a really strong call to action and I totally loved him for it. I love a cantankerous, no-nonsense kind of person. I’ve never met anyone else quite as powerful as that.

I don’t think his influence can be overstated and I’m no one to even say that because it wasn’t my community. It wasn’t my fight but what a privilege. I look back on these things and I can’t believe that I was there the day they broke the glass at the FDA and everything. It was an amazing time period and Larry, to me, he was it. He was really it.

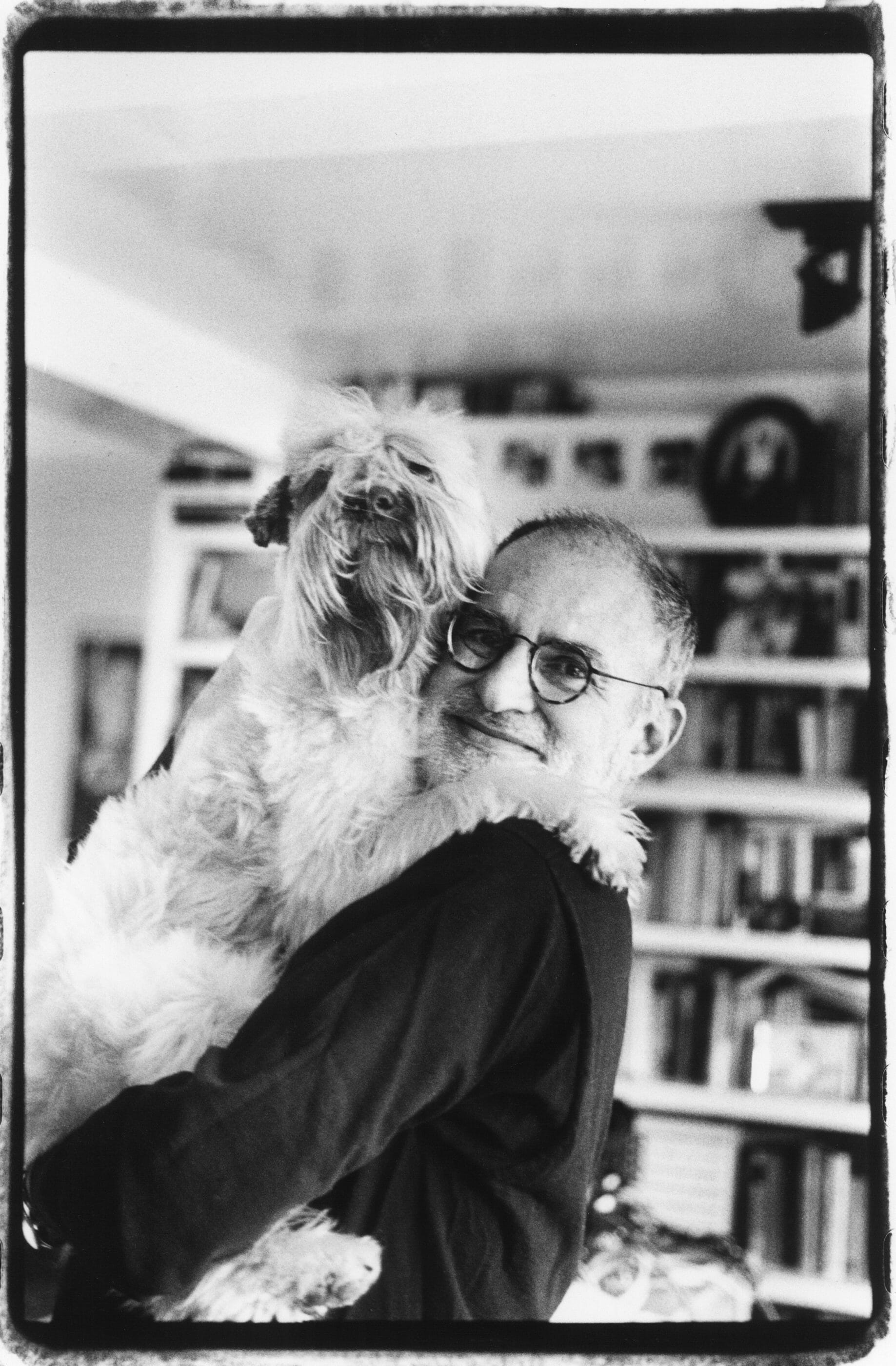

The second time I photographed him was in his apartment where he was much more of a teddy bear. I was a little nervous but it was very sweet. I think by then he was aware of his own importance. He was older and had been through a lot and lost a lot of friends, but he was also a little more at peace. He was wearing a Keith Haring shirt and had this lovely dog he was clearly in love with. I think about him all the time now that we’re in the middle of this pandemic because we need someone like Larry so much.

I don’t have a lot of my own photos around the house but there’s one of Larry that was in a show and didn’t sell, so it’s on my wall. I have to walk past him every day and I almost feel like I’m falling down on the job. I should get out there and be Larry. We all need to get out there and be Larry.

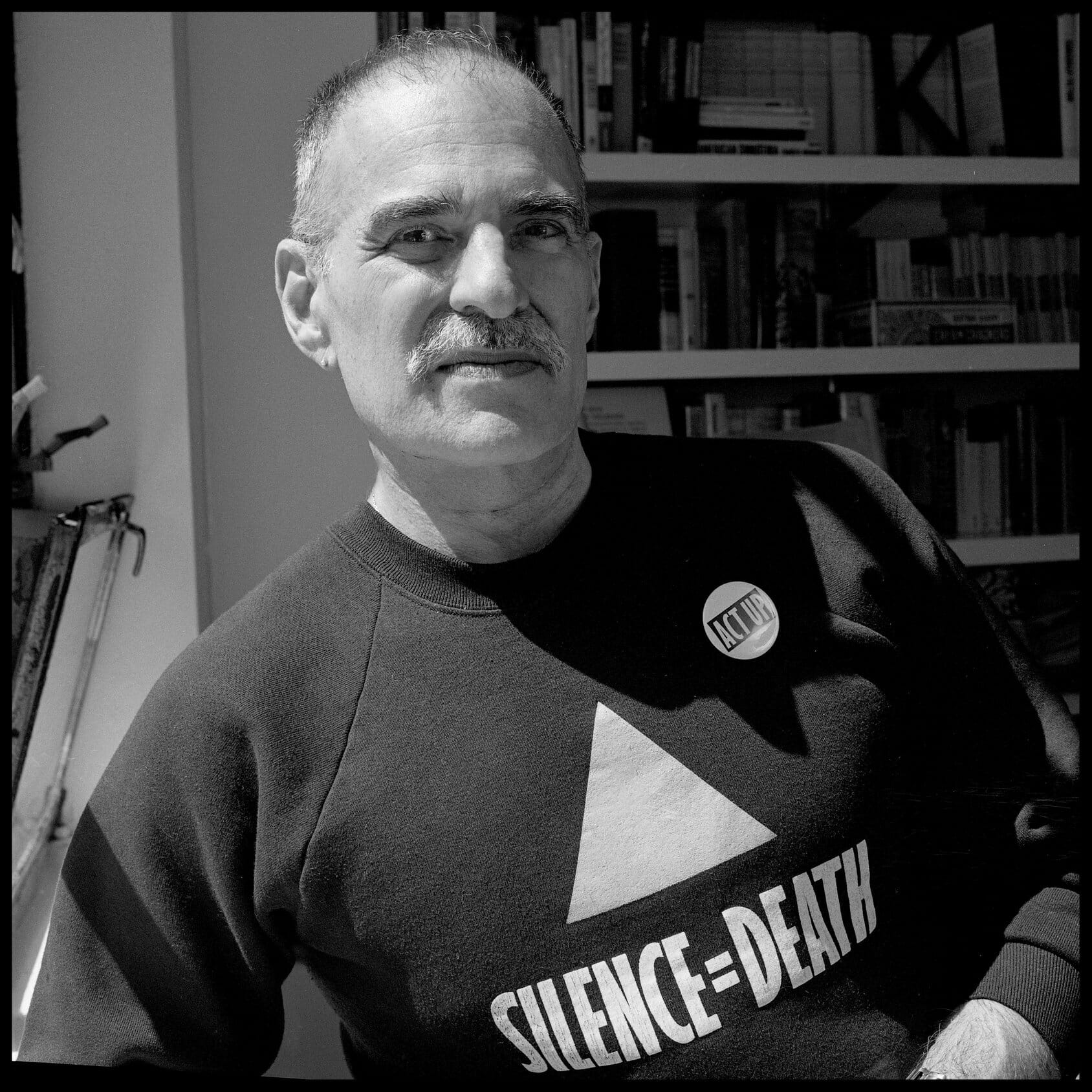

Tracey Litt, 1990

When I attended my first ACT UP meeting in the summer of 1988, I was shy and lacking in confidence and assertiveness. I had no idea how profoundly I would be forever changed when I walked through that door. I remember Larry speaking from the floor and I was in awe. The passion and fury in his words and his voice shook me. Here was a man, in fact, a room full of men and women, unafraid to raise their voices and demand to be heard.

Larry was a complicated man and I know many people had all kinds of different feelings about him. I think I was always a little afraid of him. Until the day I took this photo. It was in his apartment near Washington Square Park and Vito Russo was present. And they were gossiping and laughing and grilling me about my love life. One of them, I honestly don’t remember which one, told me I was “a catch.” I probably blushed. Larry helped me to find my voice and taught me how to use it.

Albert Watson, 1995

There’s very few celebrities who don’t have a presence when they walk in the room. Larry arrived at 4pm in the afternoon and was interesting as soon as he came through the door. And on top of that, he was a super nice person. Back then we had a massive studio and Larry just bred enthusiasm throughout the whole set.

My job is all about research and preparation, preparation and research. For some photographers, especially these days, “preparation” means you make sure your camera has a battery in it and you’ve got your lights working. We actually don’t even include equipment like that in our preparation. For us, that’s an absolute written-in-stone given. Of course the systems are working, of course we have a back-up system. Of course everything has been checked and re-checked. Preparation for us is in the whole mood of the studio, the research into the human being. When I went to photograph Steve Jobs, for example, I had pages and pages of information on him in my head. You do that with everybody and you don’t let them leave the studio until you feel you have good imagery. You don’t let them escape.

The shoot with Larry was easy, though that shouldn’t imply that it wasn’t hard work. In other words, if the sitter is very difficult and picky, you basically just do the shooting as quickly as you can. To put it in less nice terms, you want to get rid of them as soon as possible. In this case, it was the opposite. I knew about him because of his name and had heard people talk about him over the years. I was always intent on photographing him so that he looked strong because he had the reputation of being a fighter. I wanted to display him in a positive light. He was quite simply a very nice human being, that was my real remembrance of meeting Larry. And you could tell immediately that he was a powerful person.

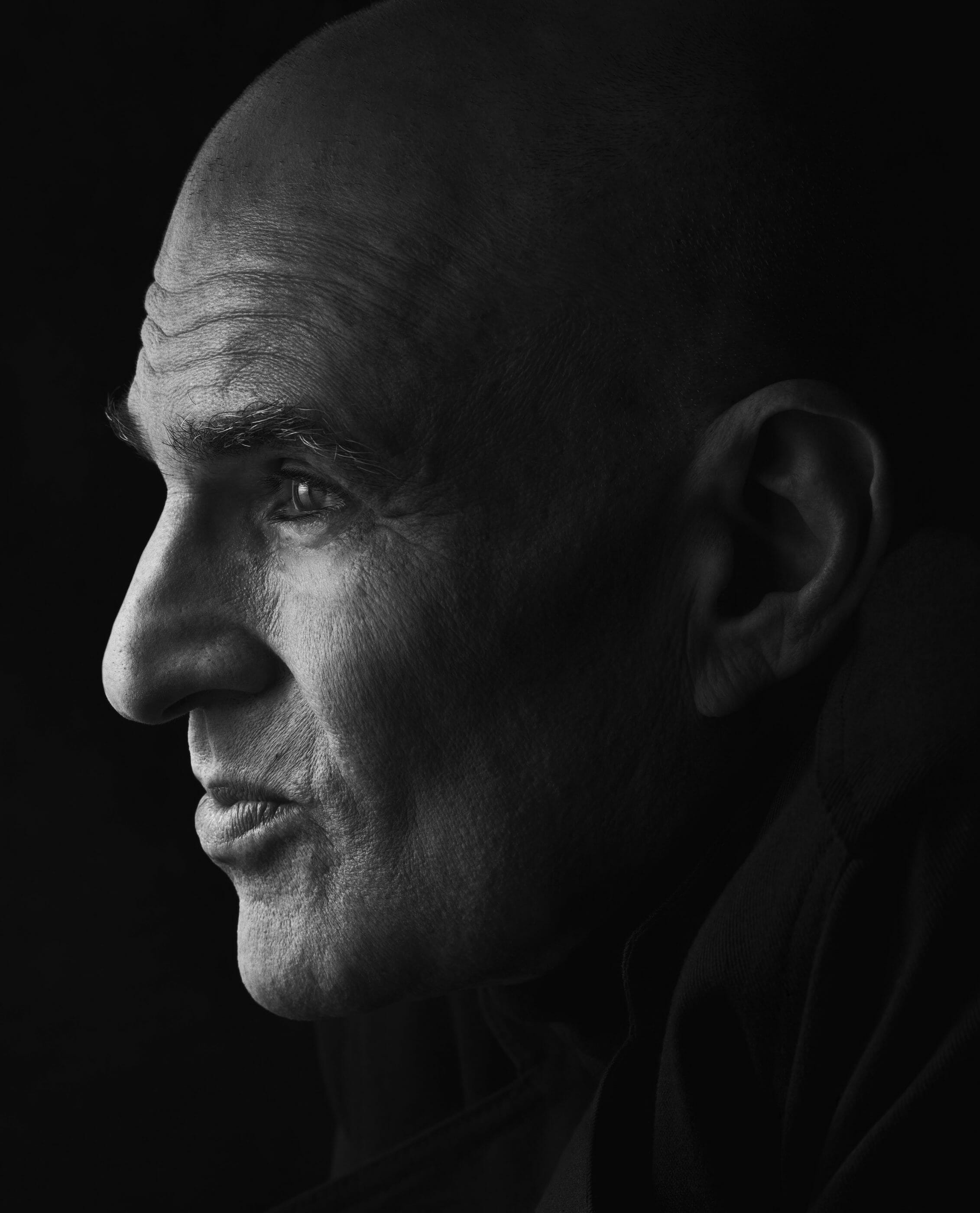

Ethan Hill, 2001

I mean, the guy makes an impression. I never spoke with Larry prior to the shoot but I was given this extremely specific shot list from the photo director and my editor at the time. They’d been dealing with him directly and apparently he’d fired back “That’s all fine, but this guy’s going to come in and he’s going to get out in an hour. I don’t care if he’s done or not, I’m kicking him out of my house.” His reputation preceded him. I loved him and he scared me.

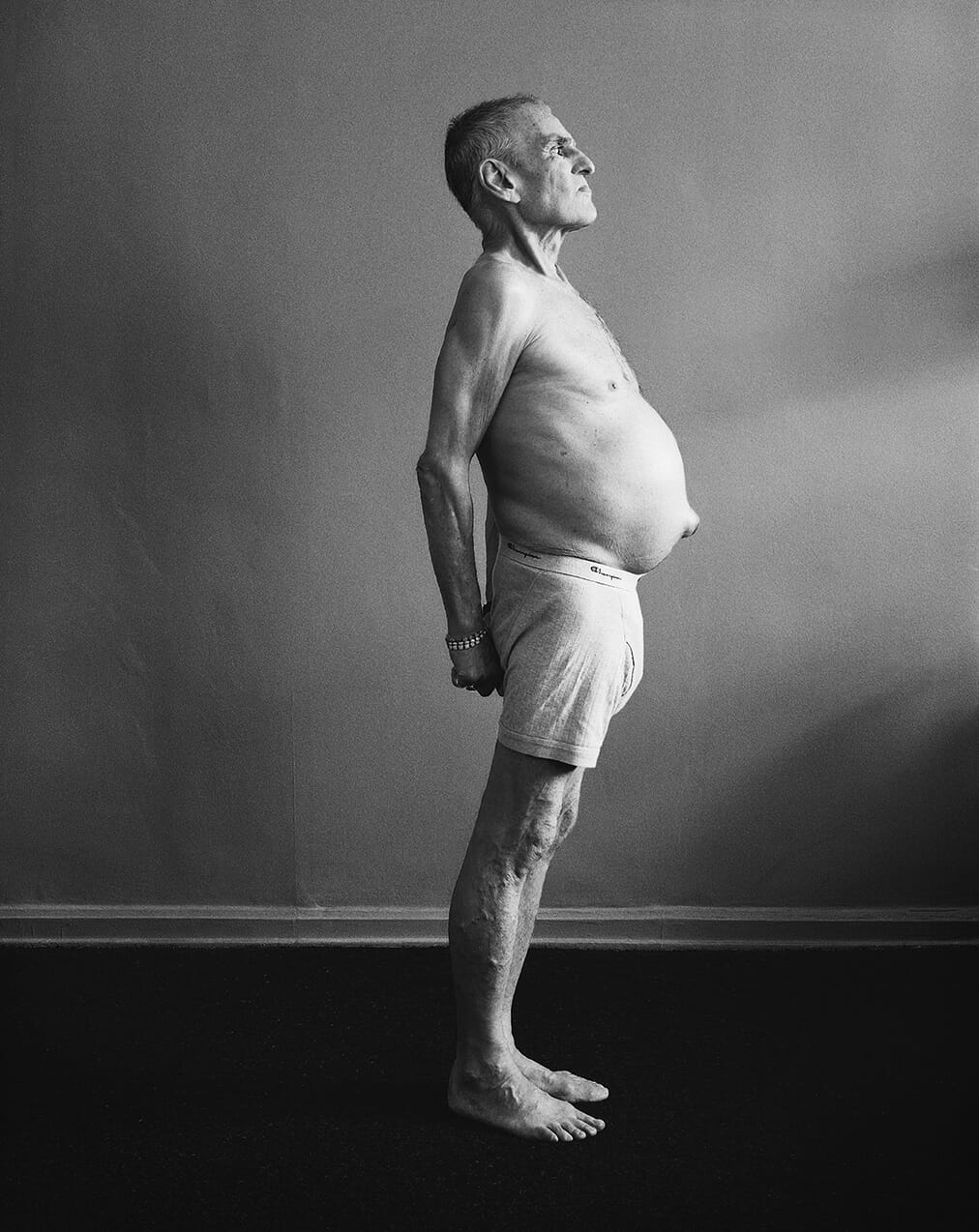

So Larry opened the door to his apartment and I said, “You’re kind of a hero to me.” He turned to David [Webster] with this huge smile on his face and said, “This guy knows who I am.” It was so humble. I had my shit totally together, going through the shot list and getting it all done. He couldn’t have been more cooperative. All of the prior HIV medication was really messing up his liver and he would have to go to the hospital every two weeks and basically get his abdomen drained. That was why his stomach was so distinctive.

This particular picture we did towards the end. I said, “Alright Larry, you know we’re photographing your stomach, so let’s do it now,” and he just stripped. I mean, he did that. I did not ask him for that. I was under the assumption that he would just take off his shirt and we would shoot him from the waist up. The damage that he had to live with at that time, visually it was just so visceral when you saw it from the side. But he just took his pants off and I thought, “Well, this is a gift.”

It wasn’t his aggressive public image. It was just window light and a guy who was totally together and if you wasted his time, he wasn’t interested. You see those videos of him yelling at crowds. I remember one that’s so clear in my mind when he started yelling, “Plague, plague, plague! You take this seriously. We’re in a war.” I could obviously see it being the same person, but here he seemed so kind to me.

Richard Avedon talks about taking that famous blurry portrait of Charlie Chaplin. He says, “Well, that was the night before Charlie was going to remove himself from America and put himself in exile. And he calls me up at nine o’clock at night and says, ‘Come meet me at the studio right now. You have to take my picture.’ Whatever. It’s Charlie Chaplin, you do it.” Then he reads in the paper the next day that Charlie has gotten on a boat and left for Europe. He describes it as this thing where, every once in a while the sitter gives you a gift and that’s what this picture was for me. It was a gift from Larry. I guess he liked the picture because he called me to come back a couple months later and he wanted to see all of the contact sheets. He referred to it as his nude. And I’ll never forget it.

Duane Michals, 2002

Everything in nature is done in abundance and variation. Nature makes 20,000 kinds of beetles, 35,000 kinds of butterflies and, in the sexual spectrum, you always have people that are attracted to their own gender. That’s just the way it works. I’m not a typical photographer and I’m not a typical gay guy. [Fred and I] lived in Vermont for 44 years. We grew our garden. Of course, we were looking at other guy’s asses and we appreciated the company of men, but we didn’t want to get down to Christopher Street.

Larry by contrast was very visible. I knew him peripherally. He was a big mouth, he was in your face. But he was a good big mouth. He was our big mouth. You need a firebrand like him, somebody to say, “The house is on fire. Put down your dresses, put down your makeup, get out of the building. Or go get a bucket of water.” Everybody needs Larry Kramer. I was never that. I usually started fires, I didn’t put them out.

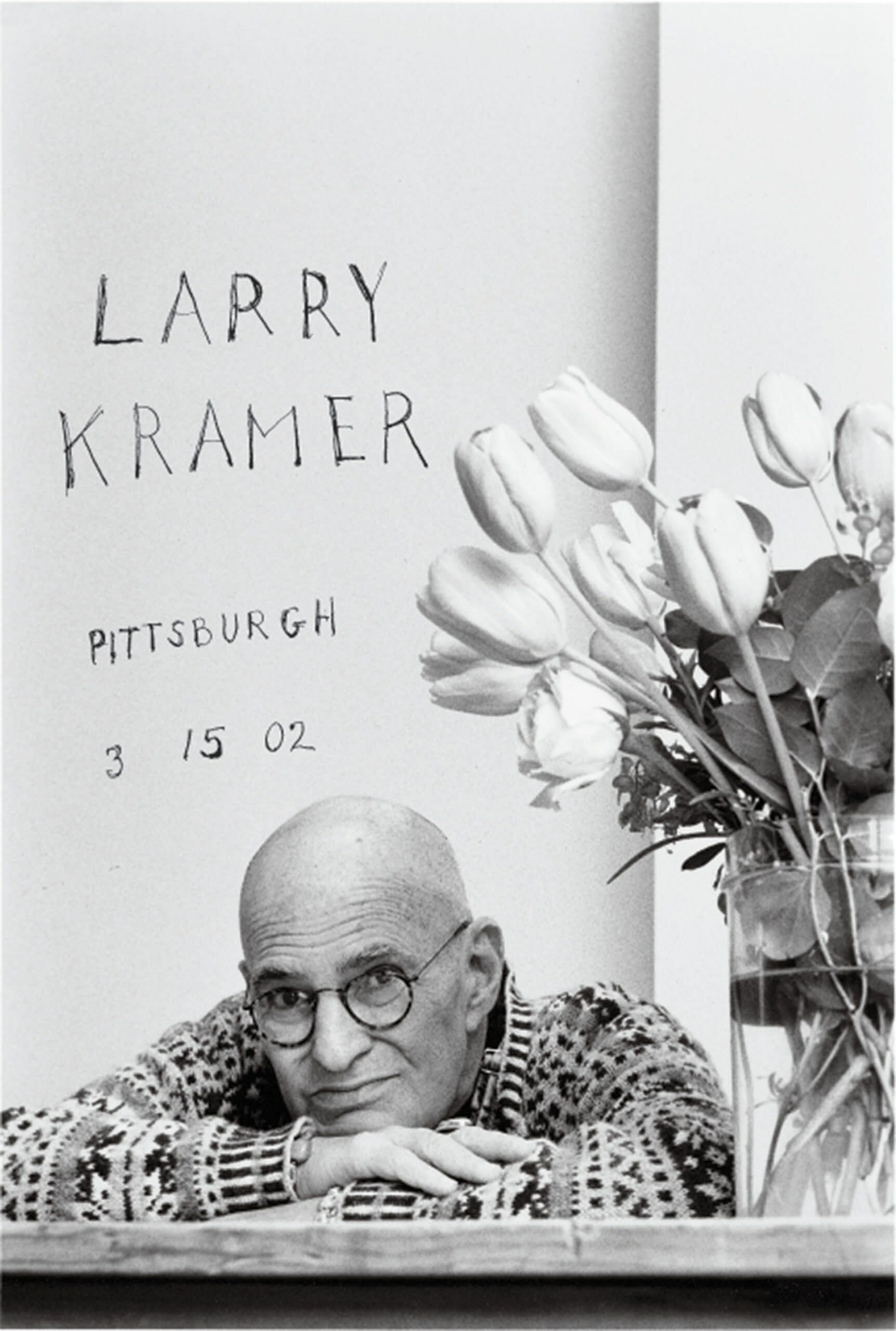

He was very annoying, though. I went to Pittsburgh to photograph him while he was recovering from surgery. I’m from Pittsburgh so I was double-treated, going back there and then meeting Larry Kramer. But he started taking over the shoot, you know? I said, “Fuck you, come over here and do this.” To deal with people like Larry, you have to Kramer-ize him yourself, you know? You can’t let him take charge.

I don’t think any two portraits should look alike and so each person should require a different solution. When you take a famous person and you put them up against a wall and then they stand and stare, what is that? It’s just anatomy. I wrote the date and location on the wall. I liked the flowers. It was all very specific to that moment. He wasn’t giving me the finger, he wasn’t Larry on fire. He was Larry the poet. So underneath all the firebrand, there was this tenderness.

The big secret I always tell students is that if you leave this school asking fewer questions than when you arrived, then you did not get an education. It’s all about curiosity, really, and most photographers don’t have any of it. I love writers because they’re interested in what life feels like and not what life looks like. Forget about fame. Fame is transient and useless. It’s only interesting to people that don’t have it. Fame should never be a goal. The goal is to be expressive, to realize you’re alive.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, 2013

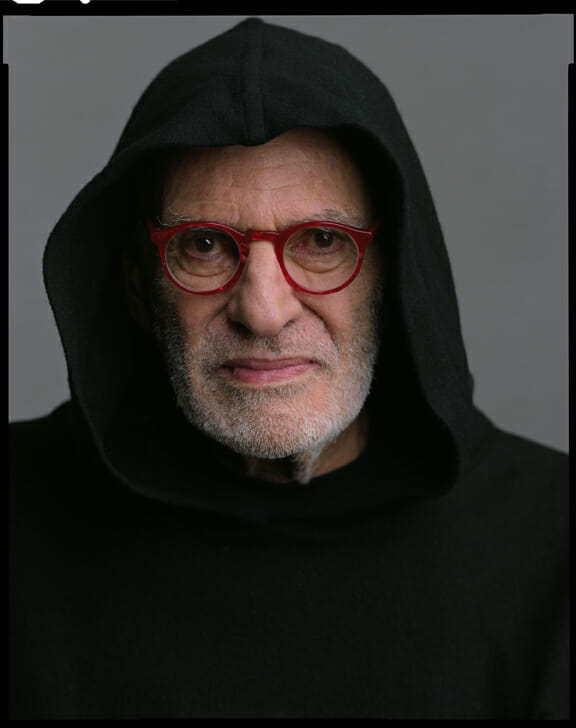

As a portrait photographer, you’re always dealing with a perception of who the person is based on what you’ve read. I try not to judge people until I’ve met them. Larry had a lot of baggage with him, in a sense, in terms of who he had been, his career, his toughness, his extraordinary tenacity. I knew about him very early on when I was in my late twenties. I was living in New York in the ‘80s and many of my friends had died. I can remember driving David Wojnarowicz to Peter Hujar’s funeral with my wife. I was very aware of ACT UP and I followed all the politics of the moment.

I can recall the day of that shoot very well. It was exciting to have him there, we all felt very honored. There was a sense that he was a truly historic figure. The process of selecting and organizing sitters for The Out List project was very complicated. The hardest thing is to decide the balance, between men and women, of professions, of ages etc. But Larry was certainly someone we wanted from the start and I don’t think it would have been as important a film without him.

He hadn’t been well and wasn’t really in a great mood when he got to us. I’m very good at sensing someone’s anxiety or exhaustion, and what they might need. So the moment he walked in, I knew to take him upstairs and sit for a while, share a little tea. All these things that one does as a photographer to get the sitter in the mood to do what we want.

Once he got to the set, he was just fabulous. I shot him both ways, with and without the hoodie, but the minute I saw his sweater I knew that it could work. I kind of saw it as “Death”, you know? He died several years later of course, but I thought he was going to die within a few months at that point. It’s not something I really do that much. If you look at my portraits, there’s rarely any gimmicks. But in this case I remember thinking that instead of just looking like an old, sick man, the hoodie stepped the image into another dimension.

Large format is a very difficult but rewarding way to photograph. You can’t just shoot and shoot, hoping you’re going to get something while wearing the subject out. You are forced as a photographer to concentrate. I try to work quickly so it’s enjoyable for the sitter. You have to know what you want. With Larry I probably shot six frames, maybe seven. And that was it. He was an amazing person.

Nathan Perkel, 2017

The weight of a person’s reputation can definitely change my approach to photographing them. Larry was really running the show when we came to his house. He was a total character. At first when he came into the room, he seemed to me to be very fragile. But knowing his history and hearing the power in his words, he still felt like a God of sorts. It was a little intimidating but he was very kind.

Being in his older years and not so mobile, we had to photograph him on his terms. He had just gotten out of the hospital and wasn’t feeling so well, but he would perk up brightly with anecdotes here and there. I loved the color of his glasses, his necklace and the energy in his eyes. The apartment was right next to Washington Square Park, right near the monument. It reminded me of an old school spot with the entrance and the doorman. It felt like I was entering a part of New York that I didn’t really get to see all too often.

His husband was really sweet and gave me a bit of advice on how to photograph Larry and not push him too much. Having [Gay Men’s Health Crisis CEO] Kelsey Louie there too helped with making Larry feel comfortable, you know? As a big fan of his work, I think Kelsey was star-struck more than anybody else in the room, not to point any fingers. It definitely seemed easiest to just let them talk and catch up while documenting him in his house. I think that’s probably how we got the better portrait of him— just snatching a moment in the midst of him chatting with everybody. I could tell Larry liked the attention a little bit.

I respected him in everything that he had done but I was definitely walking on eggshells to some extent, just to make sure I wasn’t getting on his bad side. I figured you would not want to be on Larry Kramer’s bad side. Looking back on these images now, I was just so grateful to have been able to meet him.

Joe Brennan (b. 1996) is a photographer and writer based in Sydney. His work can be found on his website and on Instagram.