Interview 062 • Feb 14th 2018

- Interview and portraits of James Hamilton by Chris Buck

About James Hamilton

James Hamilton began as a painter studying at Pratt Institute in 1964. He spent the summer of 1966 working as an assistant to a fashion photographer and did not return to school, deciding instead to make photographs of his life in New York City. In 1969 he spent five months hitchhiking and taking pictures throughout America. After showing photos from a Texas music festival to editors at Crawdaddy!—the seminal rock 'n' roll publication— he was hired as the staff photographer. This launched a forty-year career of staff positions held at The Herald, The Village Voice, and The New York Times Observer. He has worked on assignment for many magazines including Vanity Fair, The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone and on set with directors George Romero, Francis Ford Coppola, Bill Paxton, Wes Anderson, Noah Baumback and many others producing film stills. Hamilton continues to shoot and lives in New York City.

Links

Foreword

James Hamilton came onto my radar in the early nineties, when we were both shooting regularly for the Village Voice. I'd just moved to New York and had the healthy arrogance of a driven young photographer, seeing almost every shooter around me as over-rated and insufficient. Hamilton was an exception. His work was stark and confident, rich and understated. His photographs often had little going on in them but somehow still packed a psychological punch.

Over the years, he respectfully declined my several requests to interview him, as his furious shooting schedule wouldn’t allow it. In the fall of 2017, he finally agreed, and we met in Little Italy in New York for an epic three-hour discussion (likely the most in-depth interview he’s ever given).

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

How old were you when you were first coming into New York on your own?

12 or 13. I had a grandmother who introduced me to all the cool things in New York. She’d say, “Oh, we have to go to this place called Hubert’s Museum.” And it was a Diane Arbus hangout. It was on Times Square, between 8th and Broadway.

Did you ever see her there?

No, well I wouldn’t have known her. The main drag for all of the theaters was between Broadway and 8th. Every theater had its own genre. In the middle of the block was Hubert’s Museum, on the top floor had game machines – not pinball, because pinball was illegal (Mayor La Guardia banned it) – but they had other kinds of game machines. And then you pay like a quarter to go down the stairs to see the freak show. They had a guy in a turban who was the MC.

Did Arbus ever photograph there?

She was there all the time; photographing Estelline Pike, the Sword Swallower, that was a famous picture of hers. The Jungle Creep. She photographed everybody that I saw in those days, the freakier people.

I used to hang out in the Times Square area, I’d go up and down 6th Avenue, they had a whole slue of backdate magazine stores. I’d go in there and rummage through old paperbacks and magazines.

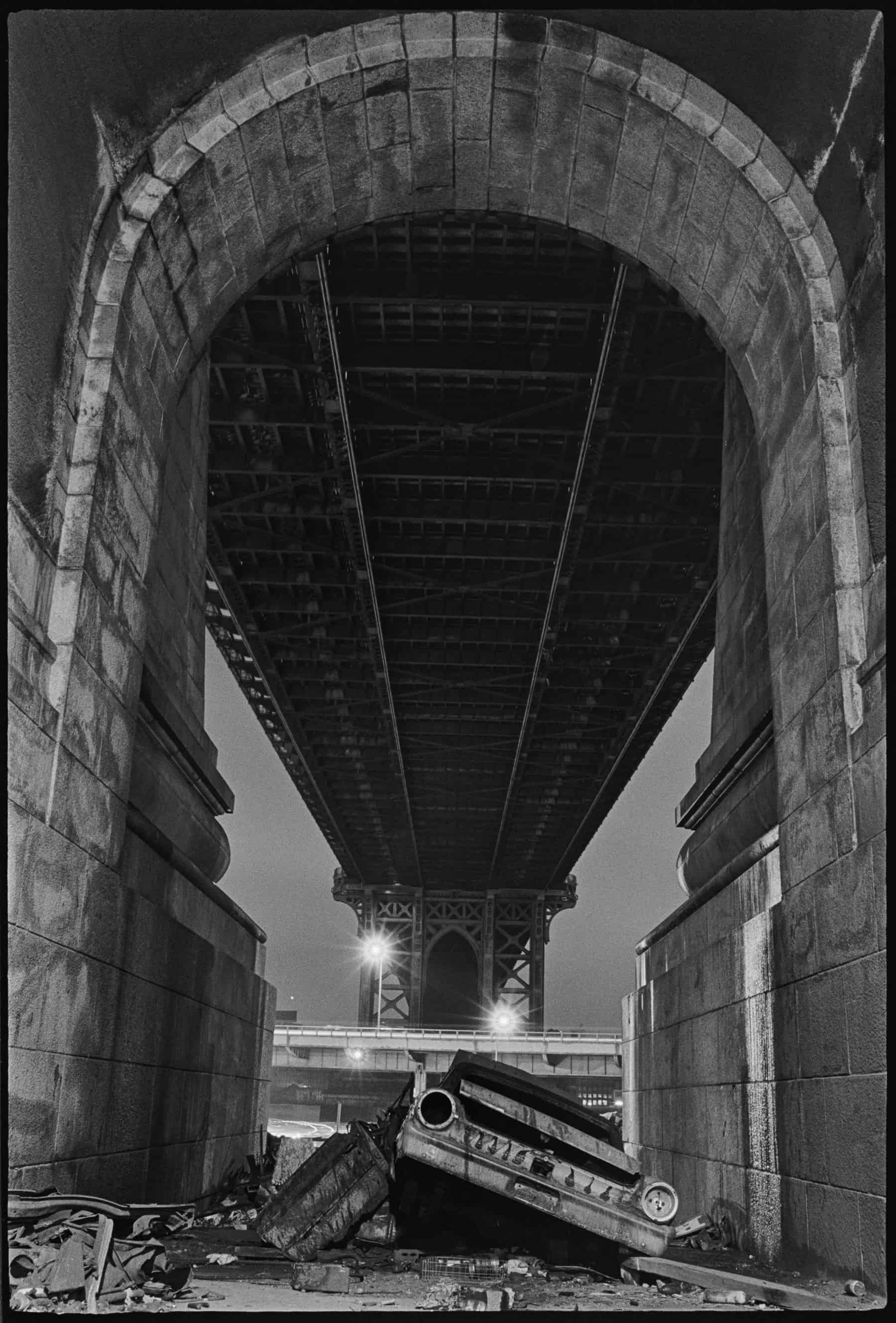

Manhattan Bridge, 1970

When did you start taking pictures in a way that was, I don’t want to use the word “serious,” but when you’re like, “I’m going to take pictures”?

I didn’t even have a camera until I was 20.

Westport, CT, where I grew up, was a bastion of photographers and art directors and illustrators. Mad Men took place in Ossining, but it should have been Westport, because that’s where they all lived.

I was interested in the artists and the painters, even illustrators, because I figured, I’ll be a painter, illustrator, or designer. I knew when I was 11 years old that I was going to go to Pratt.

My parents were good friends with the guy who did a lot of Conde Nast photography, Glamour and Mademoiselle, mostly younger people fashion. His name was George Barkentin. He was my parents’ beatnik friend of the era, and so he had a darkroom in his place, and I would go there.

He had a darkroom in Westport?

Yes, in Westport. He’d invite me over to the darkroom and showed me how it worked. And I was intrigued, but I was just never a technological person.

I started at Pratt in 1964 and in that first year I would always go home to Connecticut. I decided after the second year to stay in New York, when a couple of my friends from high school got the apartment in Greenwich Village that I am in now (in July 1966, that will make it 51 years that since they first rented it).

At the end of the summer those guys moved out with their girlfriends, and I kept the apartment. I needed a job, so through a friend of a friend, I met a photographer who needed an assistant. And I didn’t know shit; I didn’t even know what a strobe was.

When I met him, he was just starting out in New York, was this guy named Alberto Rizzo. Beauty and fashion were his thing – he was a real artist. He became part of the stable of Harper Bazaar‘s photographers.

He was Roman, and he loved all things American, especially the b&w noir movies. He was into all the things I love, so, during our brief interview we completely clicked, so he hired me on the spot…I lied and said I knew what I was doing.

It was on the job training, I learned how to work in the darkroom, like developing film; I learned everything I needed to know.

I bought my first camera, a Nikon Rangefinder, and I went out in the street to shoot, street photography. Robert Frank, and other street shooters were all influences. So I was hitting the street and coming back and using his darkroom, which was great. Free chemicals, free paper, free everything.

But did you learn how to use strobes and things like that?

Oh sure, I had to. It was mostly gorgeous women coming in and out every day.

Sounds like a terrible job.

It was terrible, so of course I didn’t go back to Pratt.

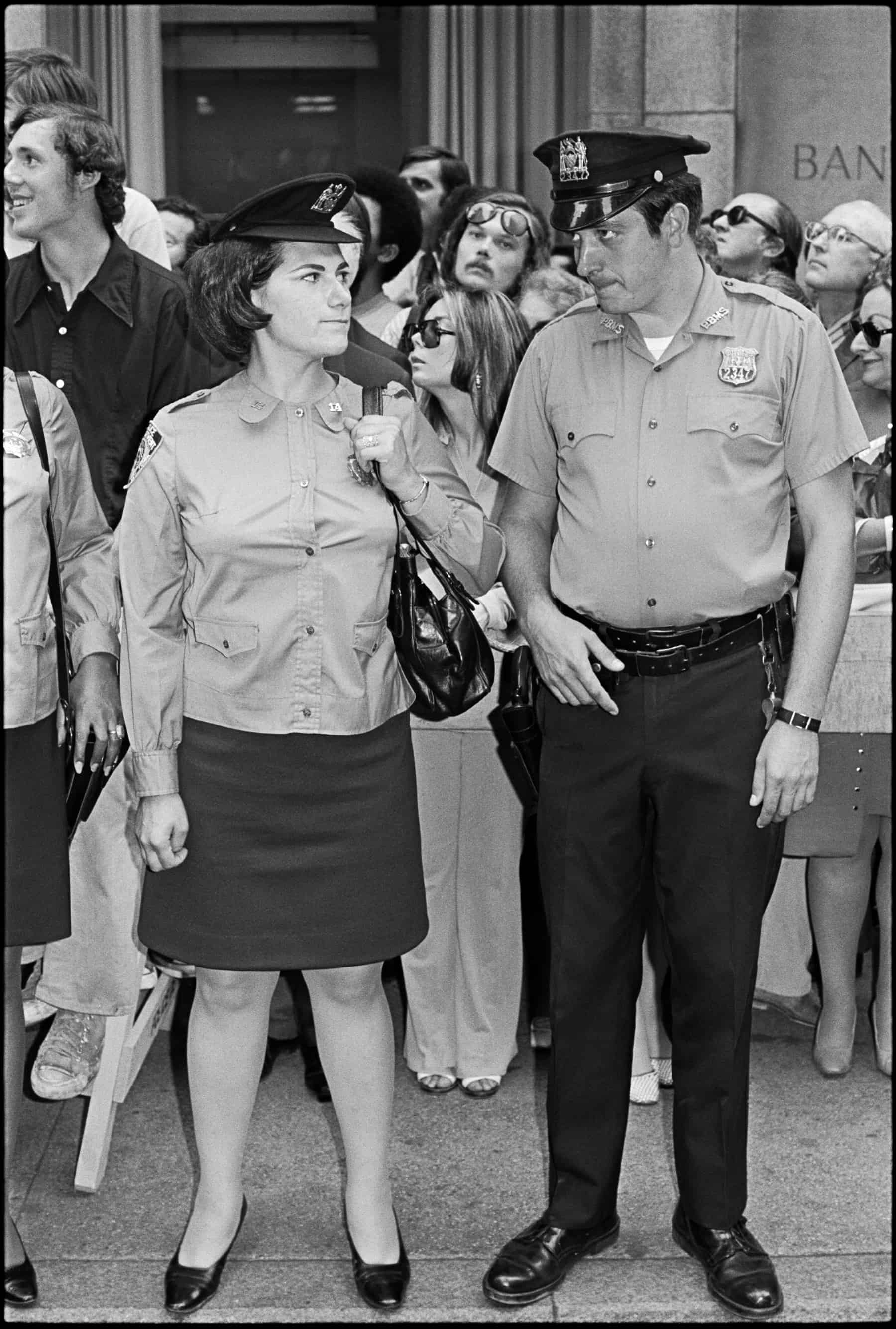

left: Women's Lib March, 1971 right: Sparkler

So you quit Pratt? Well, you probably learned more working with Alberto.

It’s the Sixties in New York, gorgeous women, I’ve got my own apartment in Greenwich Village, and I’ve got a studio to work in. I could develop my film in a darkroom, I’m learning lights and all that which is great, and I figured, I’m a photographer, fuck it, so I never went back. I never regretted it.

I worked with him for two years, lived with a girl for a while, we broke up, in the summer of 1969. I figured I’d hitchhike around the country. I spent five months hitchhiking, including a rock ‘n’ roll festival in Texas, it was sort of a mini-Woodstock around a lake in Dallas. It was called the Texas Pop Festival. I went to a stationary store and forged a press pass.

I shot all these great pictures, including Janis Joplin, Johnny Winter, B.B. King, Grand Funk Railroad. I’d picked up my best friend’s girlfriend in California.

I’d just broken up with this girl, Richard had just separated from Lynda, and she was out in Southern California visiting her brother, so I figured, oh I’ll go down to visit her, and then we wound up…(chuckles) when I was about to leave, she was like, can I come with you, so here I am hitchhiking with a girl…to think of doing that now?

Were you taking pictures on the road the whole way?

Oh yeah, with my Lloyd bulk film roller. They still make them, it’s these big black thing, you get 100 feet of Tri-X in a roll. You put it in this black box that’s light tight, and you get these empty canisters to snap on canisters.

So that’s what I did to save money, so I rolled my own and shot hundreds of rolls all across the country.

When do you think you went from getting the occasional interesting shot, and enjoying the discovery to being a photographer, to becoming one who has some clarity of vision?

I’m currently going over all that stuff now, starting with the Seventies.

I always thought of my portraits, especially early on, as an extension of my street photography, not the other way around. I never really thought of myself as a portrait photographer.

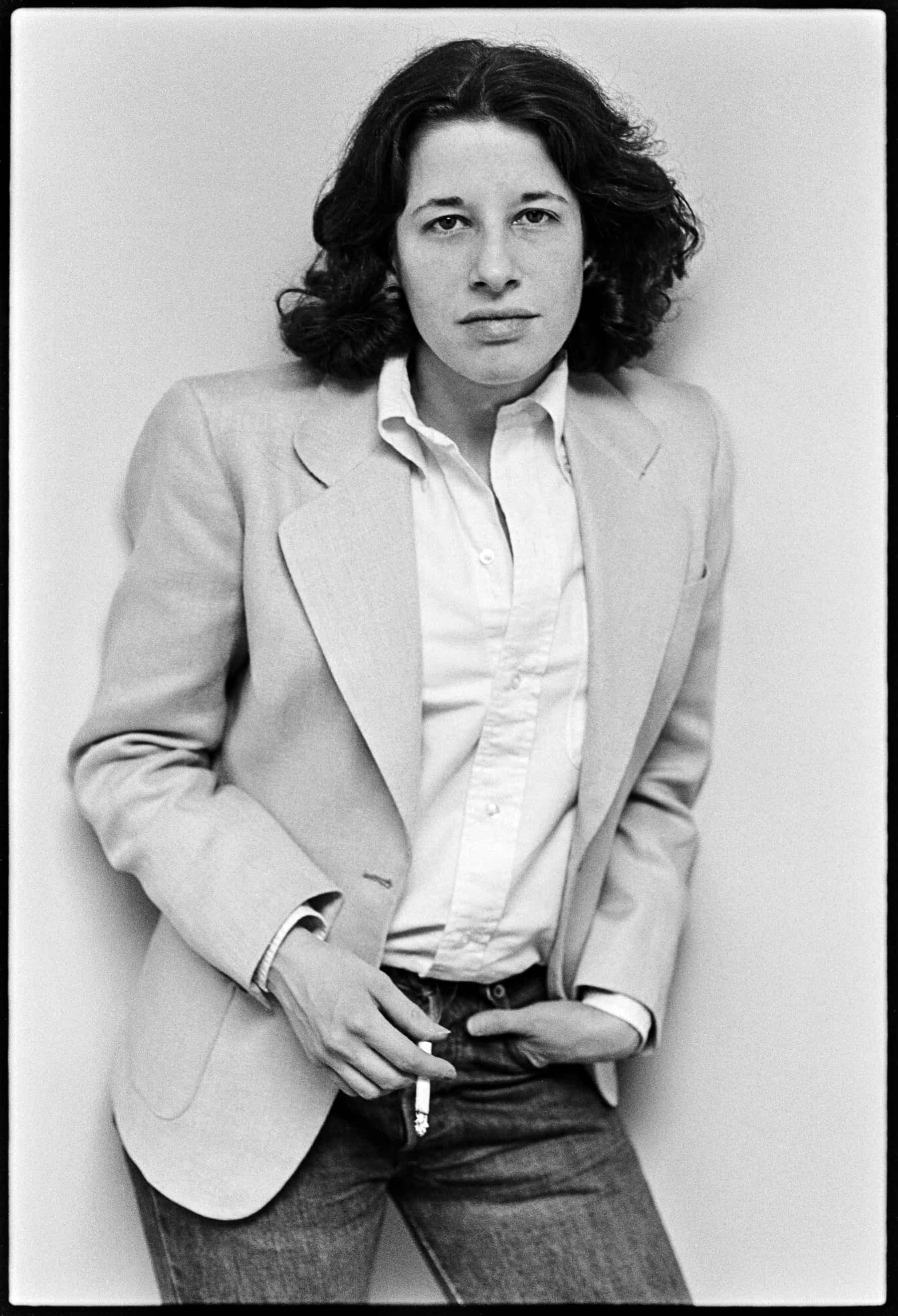

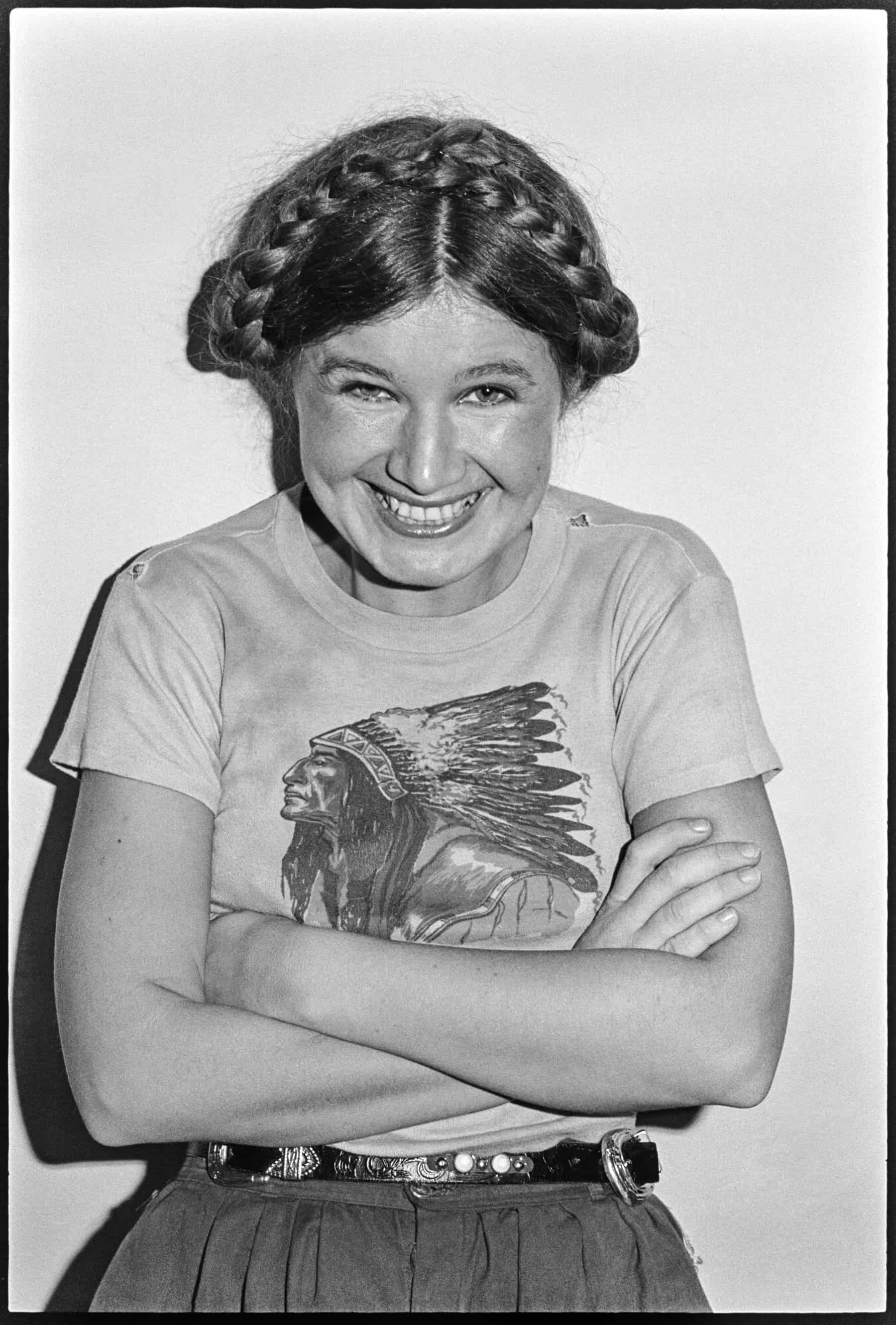

left: Fran Lebowitz, 1978 right: Meryl Streep, 1976

Are you willing to own it more now?

Not really, it was a necessity, you know how it is.

But don’t you think there’s a difference between a reportage photo and something made in a directed sitting? Let me use an example from your music book to illustrate. Here is a shot of Diana Ross shot candidly walking into a room, and Dusty Springfield as a stand-alone portrait. They’re both great photos, maybe it’s my bias because I love portraits but to me there’s something extraordinary about the Springfield one.

It becomes isolated from the world, because even if it’s only directed in the most simple sense of, “Hey, can I take your picture?” and she gives you 60 seconds or whatever, there’s something about she’s broken from her life to connect with you to make a picture.

There’s something about this that is locked in time as being unique and different in a way. There’s nothing fancy going on or whatever, but there’s something magical about it. To me you are a great portraitist.

Well it was, again, it was like that’s what the market demanded.

And I loved the process of doing portraits, but I’m just as happy doing landscapes, pictures with no people at all, and I’ve been doing a lot of that.

But don’t you think that portraits are more difficult?

Yeah. They’re more difficult because there’s more of a demand on me and them, you know, so there’s that. It can be a lot of fun, it can be torturous, rarely, but sometimes.

Define “torturous”?

When somebody is utterly uncooperative, utterly couldn’t care less. I can think of one prick that I worked with – Michael Dukakis was a real asshole. And I was merciless with politicians, anyway.

If you look at the contact sheet there’s not one picture that I like, except for the contact sheet itself, and it’s because in every picture he’s the same. He wouldn’t do anything, so that’s what’s funny, the contact sheet.

I’ll briefly tell you my career. When I came back to New York from that summer of hitchhiking with my new girlfriend, who had been my best friend’s girlfriend; we lived together for 7 years in the end. We moved into the apartment, and I built a darkroom kitchen, basically, which I still have and still use. And so I developed the film from the Texas Pop Festival and I heard that there was this rock ‘n’ roll paper starting called Crawdaddy. I went in there with these photos, Crawdaddy hired me on the spot.

My memory of it was that Crawdaddy was more esoteric than Rolling Stone? It just had weirder stories.

Yeah, when Jann Wenner brags that Rolling Stone took Rock ‘n’ roll seriously before anyone else did, that’s bullshit, Crawdaddy did.

It was sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll, because the editor wound up being this guy named Peter Stafford who was very into acid – writing about acid, and the history of acid. Fantastic guy, and he doesn’t care about music at all, and didn’t know about it.

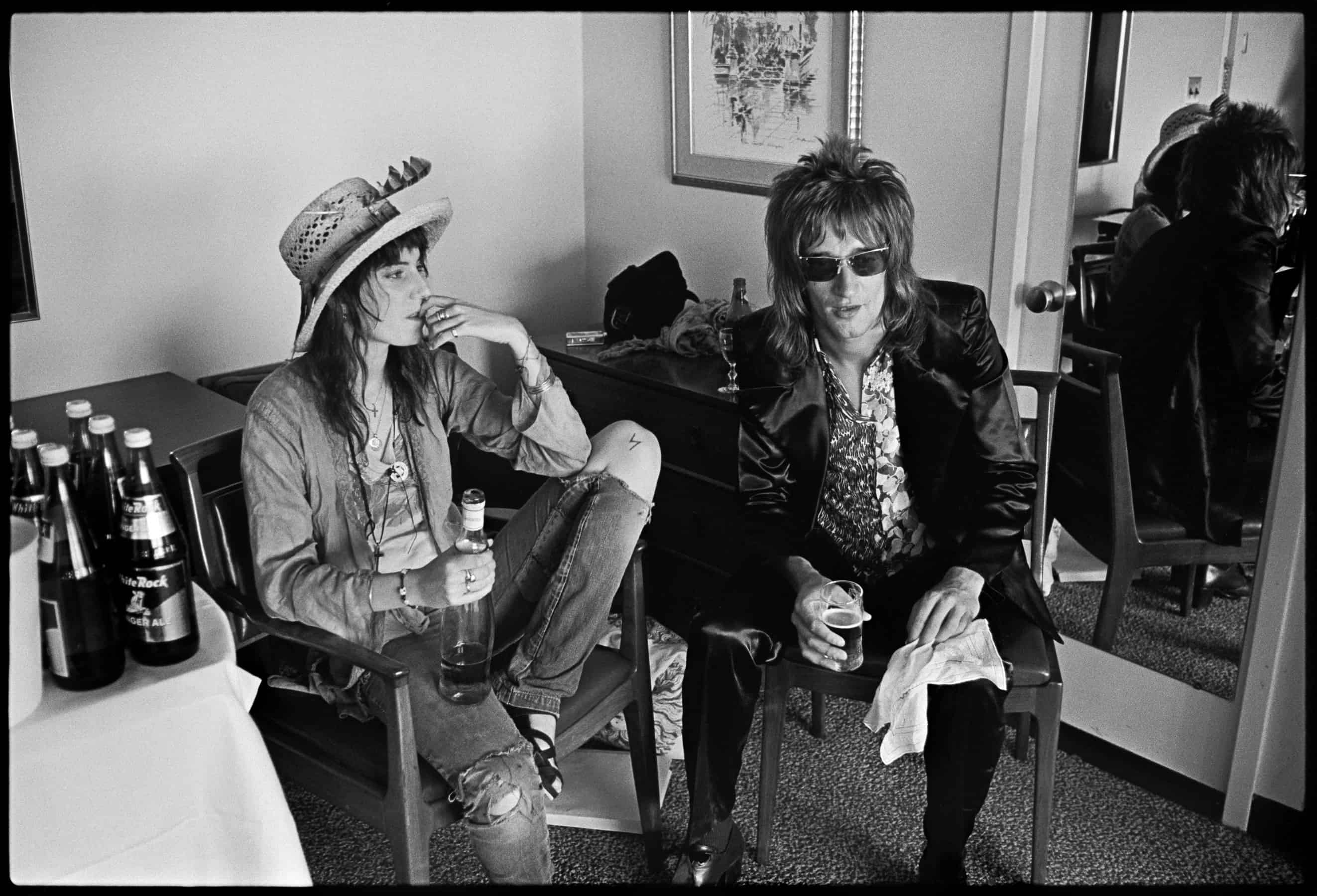

Patti Smith and I would go out and do stories together about musicians…there’s that picture of her with Rod Stewart. So that’s from there. She was writing Rock criticism and stuff like that.

Patti Smith w/Rod Stewart, 1971

Was she already identifying herself as a poet?

Yeah, in addition to.

But you just thought of her as being someone you work with?

No, I met her as a poet, a poet introduced me to her. Although I was in the same class as Mapplethorpe at Pratt, and I would see him around the school.

I want to hear the story about the Rod Stewart picture, it looks like she’s looking at him and saying “I want that hair.”

(laughter) That’s why she wanted to interview him, she loved that Rod Stewart look.

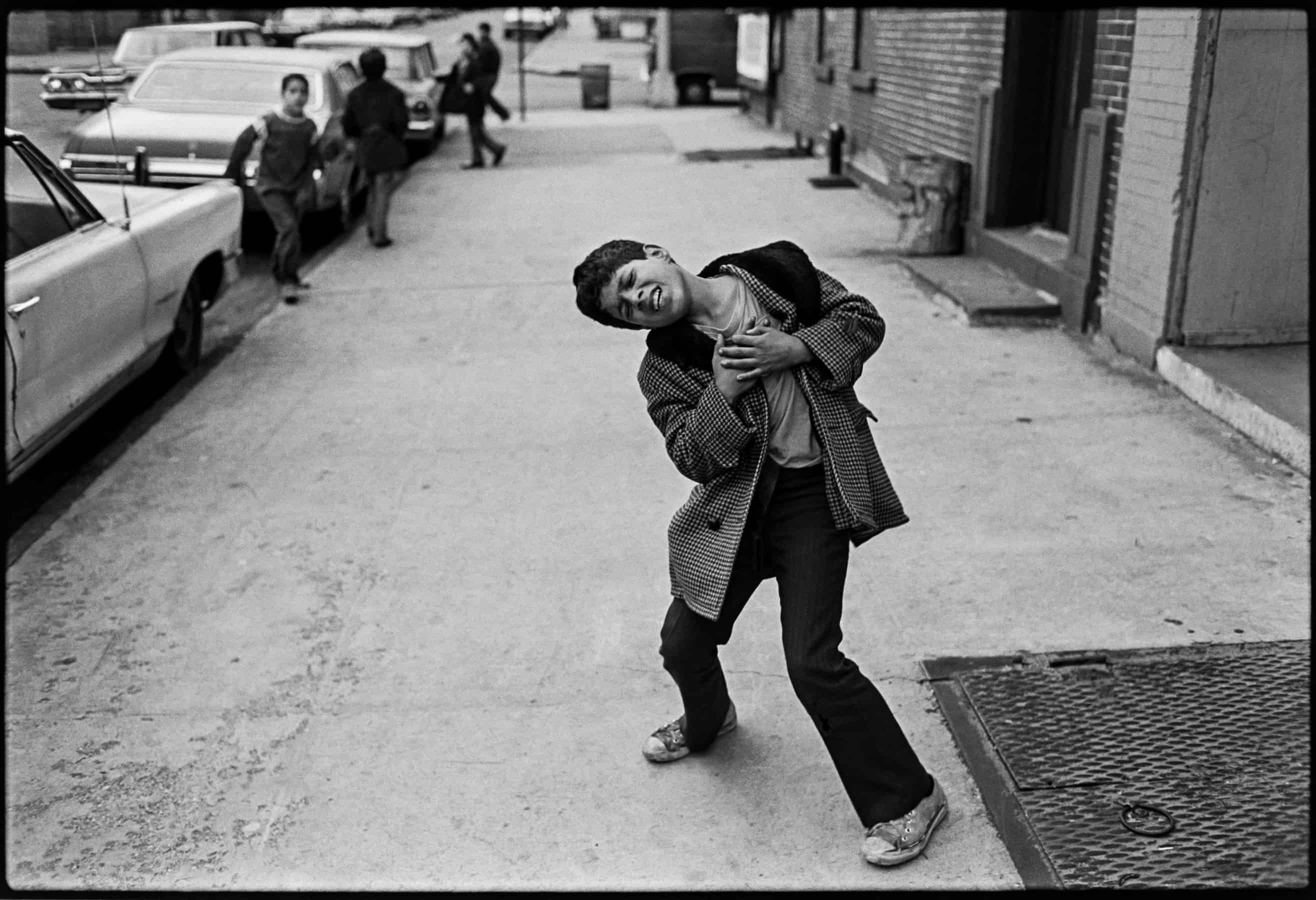

You mentioned earlier about going sorting and scanning your old negatives. Much of it is observed, or street photography.

Well, it’s mostly about New York. One of the hugest subjects was kids. And they’re not sentimental, they’re not corny. And it’s this major collection, so I’m having fun gathering those street photos.

top: Playing Shot, 1973 below: Woman Dog Under Skirt, 1994

At some point I want to ask you about some of the portraits in the Should Have Seen What I Heard book (of music figures).

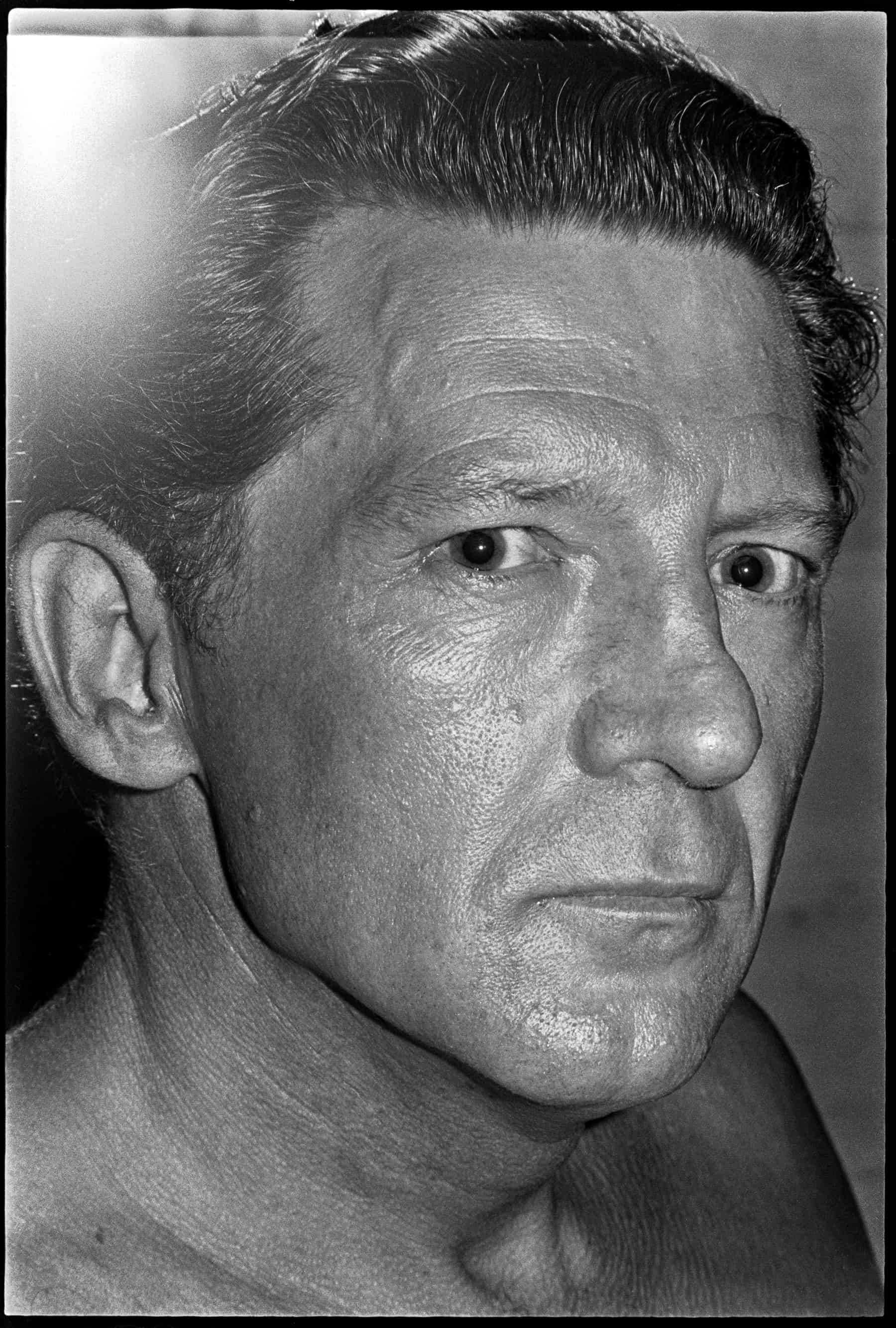

I love this page with Jerry Lee Lewis, I mean, wild, crazy, like a Southern maniac. He had just thrown a knife at me. I photographed him at this club he’s played great, and then I went back into the pressroom to photograph him; he was shirtless, with black pants on. I realized then that he was shitfaced, and he had been so the whole time he did the show, but he held it together. I’m sitting over there loading my Tri-X, and then all of a sudden, a knife goes right here [points next to his head]. And he yells, “MUWAHAHA.” One of those drunks.

Jerry Lee Lewis, 1979

Bea Feitler hired me away from The Herald, to be the first and only staff photographer for Harper Bazaar. That meant parties, events, things like that. The first gig was the Women’s March in 1971. She completely fell in love with the pictures, and they ran them.

We got very conspiratorial, because what had happened was, a guy named James Brady came in as the editor, and he’d come from Women’s Wear Daily, so the dictate was, we want to make this work. More newsy, more tabloidy, obviously still fashion, but we also wanted to have this other quality, and Bea thought I’d be perfect for that. We got conspiratorial about these party pictures, because Brady was sucking up to all these society party people, but Bea and I were satirizing it the whole time, big time, if you saw these pictures…and we got away with it.

She hired me to do this, so the first party I was going to go to do was this thing called the Plaza Ball. I didn’t have anything to wear so I went to this place, and I said, “I need a tuxedo.” I figured I’d play the Harper’s Bazaar card, but I needed it by that night. (chuckle) I went for the fitting in the morning, and they had it ready by nighttime. And it was a really great looking tuxedo – black velvet. Can you believe it? This was 1970’s.

Sounds warm.

It was warm! But it was December. So I run to this place, get the suit, put it on, had my camera, run over to the Plaza. Run in, and first thing that happens is I walk in and Gloria Swanson comes over and says, “I love the suit.” (laughter)

I always like to think that I’m in a bubble floating around the room wherever I was – invisible – which was the ideal scenario, for me, anyway. To feel utterly invisible. And that’s how I shot. They would send me out of town to Nashville to photograph some society ball down there. I felt like a hit man. It was so funny, I’d be flown into town, do the thing, then run out of town, then Bea and I would have a ball laughing over these pictures.

I wouldn’t set up situations, especially back in those days, I was always on the run catching pictures. It was so much more fun, and that’s what I mean, when I compare that time, when I would run around with people rather than set up in a hotel room for ten minutes.

I shot Hitchcock one time, when Frenzy was coming out, and they weren’t interested.

Harper’s Bazaar wasn’t interested?

Yeah, they weren’t interested, but I could call up anybody and say “Hi, I’m the staff photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, I’d like to photograph Alfred Hitchcock,” and they didn’t question it. They didn’t say “Is it going to run? Is there an interviewer?” So I go to the St. Regis, knock on the door, Alfred Hitchcock opens the door, I walk in. We sat there an entire afternoon, talking, laughing, having tea. That was what I loved about it, because the world was my oyster.

How much did you shoot with him?

I think I shot one roll.

You shot one roll and talked the rest of the time?

Yeah! I know I only have 2 contact sheets. So one of them was posed, and it’s a good one but it’s not my favorite, my favorite is with him laughing, because that’s the kind of afternoon it was.

left: Betsey Johnson, 1971 right: David Lynch, 1986

I saw on your website it says you sell prints. How often do you actually sell prints?

A friend of mine set that up.

So you sell prints now, apparently!

I would like to. Well, you know, I’m learning the ways of digital. I was always a good printer.

It actually says traditional silver prints, just so you know what you’re selling. So…then after Harper’s Bazaar you got hired by The Village Voice.

George Delmerico had been at The Herald, and he said why don’t you come on board with The Voice.

So how long were you at The Voice?

20 years. I started in 1973 and left in 1993. So I was brought in and Sylvia Plachy was, I think she was brought in after me.

Fred McDarrah was there, but he wasn’t really doing as much, he was sometimes doing politicians. So I was brought in by my friend George, and Clay Felker was running it then…so I went through all those regimes, and then I started doing an enormous amount of work for New York Magazine, so I was almost staff there; I just did covers, that kind of stuff. And that was almost all color, it started black and white and then was all color.

Are your subsequent books going to have color in them? Even peppering in some color, especially of historical things, it ends up being a fun jump into color.

That’s true. I’ll see, I haven’t really thought it out. So yeah, I worked there for 20 years, and as I said, the Observer offered me this other gig, and what happened was this: I was starting to do a lot of war photography at The Voice, like ridiculous stuff like Graneda, but also serious stuff like Salvador, Nicaragua, things like that.

Because you’re on staff?

Yes. The variety of stuff I shot for The Voice…they sent us to the Philippines twice to do the Marco’s overthrow; can you imagine doing that now?

I was always paired with writers, Mark Jacobson, Michael Daly, all these, they would pair us. And Jacobson and I had a ball doing stories, drive across the country, pick up stories…

Wow.

Joe Conason was one of the writers I was working with, and we had been bugging them to send us to China because all the students were in Tiananmen Square, and we just wanted to go. And then, when it looked like it was all going to be over, they said, “Okay, you can go.” We got there when the confrontation with the students happened.

A lot of the Beijing students were pulling out, getting up, whatever, but the kids from the provinces, and they started filling up the Square, and that’s why there’s no real body count. Who knows where, they came from all over China, and so then, we got there and it all happened.

I gathered up all of the film, or as much of it as I could do, so it’d be on The Voice, and got it out through civilian couriers, civilians, because they were confiscating shit at the airport, so much stuff…but while we were there, there were pictures of dead Chinese students on the cover of The Village Voice.

How’d you get them back to New York? Did you send the shot film, it wasn’t processed?

Yeah I sent the film, it wasn’t processed. It was very dangerous, but I had no other choice. We were still there.

So then we stayed for a few days. We had bicycles, which was the best way to get around, so we could go where cars couldn’t. They took us to this warehouse near a hospital and there was a makeshift morgue. We broke into the warehouse, and we were unzipping body bags. We were literally unzipping body bags and using a flash, and eventually, somebody saw the light, we heard cars coming in and we tore out of there. I was racing on my bicycle, tears streaming down my face from what I had just witnessed.

Tiananmen Square, 1989

And these are teenagers that you photographed?

Yeah, I’ll show you some pictures. Already maggots…so when those pictures ran, I got a call from the London Sunday Times and they needed someone to go to Ethiopia to cover the war.

They said that they’ll pair me with a writer, who turns out to be this Marian Fitzgerald, who knows Africa quite well. We meet in Khartoum, and I head over to Ethiopia to take pictures. I was told it would be a few weeks and lasted four months, because we were in the wild, there was no way to communicate with the outside world. I’m basically covering war in the jungle.

When you were starting to get serious about photography in the early 70’s, what photographers did you look at as a kind of role model?

Robert Frank. I loved The Americans.

I actually loved Eugene Smith, and after I came back from my trip across country, not just the rock ‘n’ roll pictures, all the pictures I took, and I knew where he had a studio, at 6th Ave and 30th street, and I just randomly decided I would go to him and show him my work. I think that it was a pilgrimage for lots of people. I showed him some pictures, and there was one picture that moved him to the point of tears (he was an easy cry).

What was the picture?

It was a picture of a camper and two little girls playing catch. It was a very moody, and kind of beautiful. It was taken in North Dakota or South Dakota, and it has this strange feel to it. It moved him, and it was on the heels of, do you think I have a future in this racket, like anyone could take this picture, etc, etc.

top: Trailer, 1969 below: Mercedes Tomb, 1984

Did you take pictures of him?

No! (laughter) I didn’t have the nerve to do a lot of that!

You’re no longer a working photographer, how did that come about?

Since 1993 I’ve been on staff at The Observer and they brought this new art director in, it was the only time in my life that I had problems with an art director, that’s how lucky I was. She made my life hell because she started cropping my pictures, and she was using bad pictures, it was just fucking awful. To the point where the last few years of the Observer were so awful that I am lying under the wheel of a Cadillac Escalade, 2009, February 1st, and my very first thought was thinking, “Thank God I don’t have to work at The Observer.”

Why were you lying under the wheel?

Because I got run over.

I was crossing the street in Brooklyn Heights at Henry and Montague, and a Cadillac Escalade knocks me down, I land right there, it separated my foot from my leg.

You walk pretty well, considering.

It took four years and four surgeries. That night, Long Island College Hospital was right there, so they pick me up, took me there, put all this metal in there. But I couldn’t walk, and it took four years of therapy.

An orthopedist ran me over, by the way. My friend Julie was waiting in my Jeep up the street, she sees this crowd gather and a camera lying in the street, and she comes over, and I said don’t look (after they had backed off of my leg). So she got out her notepad and started taking names, very subtle, then she goes to the black guy who was driving and goes, “Is that your car?” And he says, “No it’s his,” and this guy is hiding, jumped out of the car, and he’s an orthopedist! If it had not settled, it would have not looked good in court.

But it took four years for that, too. So anyway, that was my very first thought. Thank God I never have to work at this paper anymore. I was on my way to photograph a real estate office in Brooklyn Heights, that’s why I was there.

Yeah. So do you still shoot?

What I’m mostly doing now is scanning. Julie Mihaly will come out to my place in East Hampton, and we flatbed scan negatives. It took two of us to do it rapidly enough, and I said, “This is fucked. I hate this.” So what I do now, is I photograph my negatives, with a Nikon, at RAW at 100 ISO.

And you can actually render an actual picture?

Gorgeous!

I’m almost done with the Seventies, all my street pictures.

top: Waving Street Couple, 1971 below: Kissinger Motel Sign, 1979

I hate driving back and forth, so I leave my car at the train station, take a train in, and I mark contacts sheets all the way in and all the way out. I’ve got one year to go, 1977 I think. I did 1979 recently. Anyway, so I just go month-by-month and I can knock off a year in a weekend.

The weird thing is that I’m reshooting all my photos (laughter) it’s like it completely takes me back to pictures that I have no memory of, and it’s as if I’m shooting for the first time. Sometimes I think, “Jesus these are good, who took these?”

Where’s this drive from you, I remember seeing you at The Observer…I’m like “Wow, that’s impressive; you’re still doing it.” What drove you to still be a staff photographer that long?

The opportunities, really. The luxury of doing what I wanted, and getting paid for it. At The Observer, for many years before Jared Kushner came in, I was doing those 2’s and 4’s, that’s like, what a dream, that’s like having a column! Being a cartoonist, you know, why wouldn’t I want to do that?

And then I shot all the other pictures in the paper, too, you know. 90% was black and white in those days, the only color was for the illustrators, and the illustrators would write me letters about how much they liked my work.

And it’s not just that you’ve worked a long time, the work itself is special.

I like to think it is, but I’ve never been asked to be part of a show. I’m not known in the gallery world, certainly. I’m not known by anybody, but by photographers, and the occasional art director.

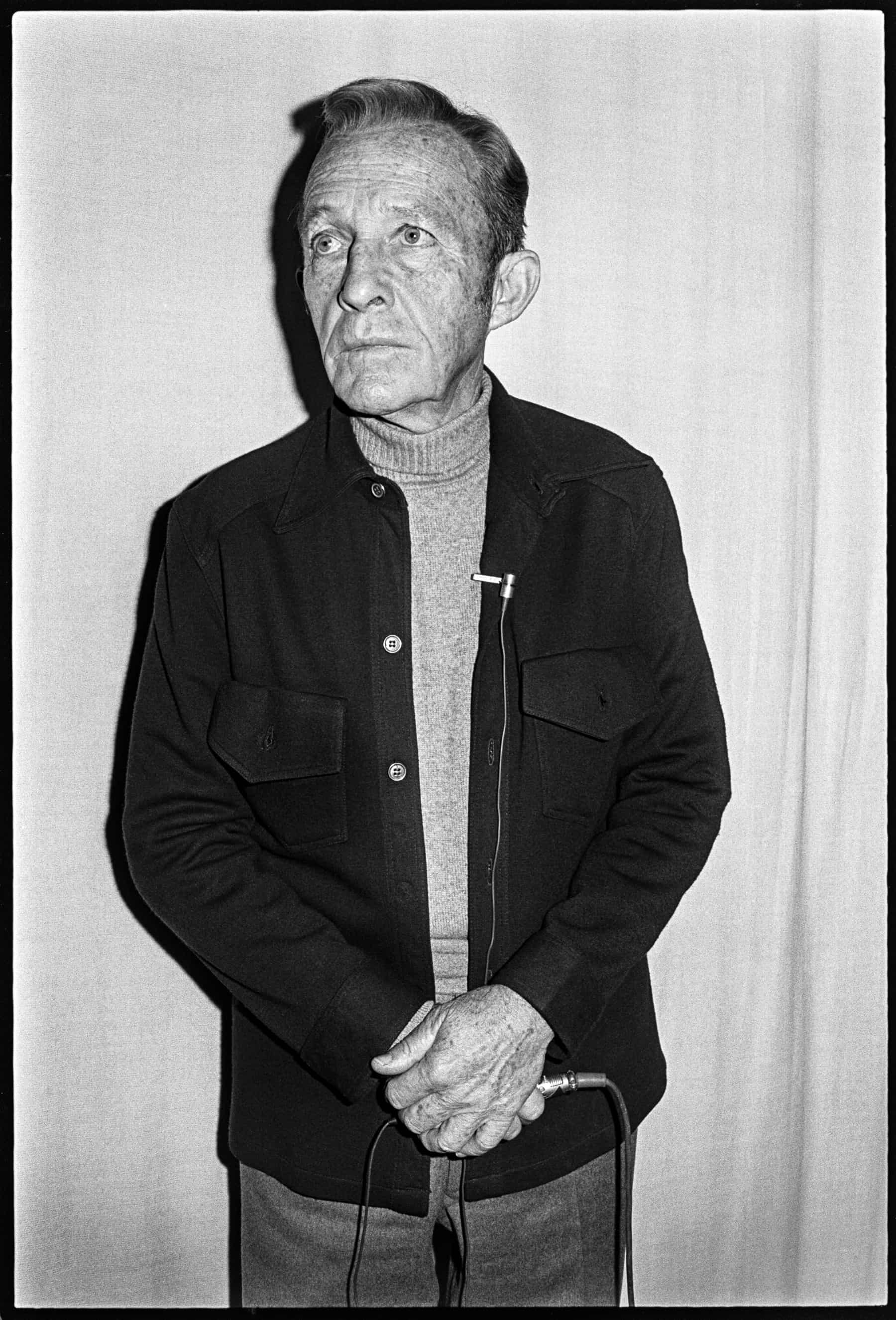

I’d like to ask you about the pictures that jumped out at me as being interesting. Bing Crosby.

After my mom got divorced she moved to the city and ended up being the production coordinator at a show called Mid-Day Live, an afternoon talk show on Channel 5. Everybody would show up there, it was fantastic. So she would call me up and be like, “Bing Crosby is going to be here. Get up here!”

Bing Crosby, 1976

And they just give you access?

Well, because my mom was the production coordinator, she booked the guests.

But no one asked you what’s this for?

No, no. They assumed it was for the station. Nobody asked, ever. And so, I photographed Jimmy Hoffa a month before he disappeared.

Oh my God.

She would call me anytime somebody cool or interesting was going to be there. I would race up there with my camera and shoot them backstage somewhere, often against a white curtain, like Bing Crosby.

And so again, opportunity.

My mother totally got what I was doing. She told me, “When I see your pictures in the paper, they don’t look like anybody else’s, I always know your work!”

It’s important to have that kind of support.

Both my parents were extremely supportive of me, no matter what I wanted to do. So that’s how a lot of those happened.

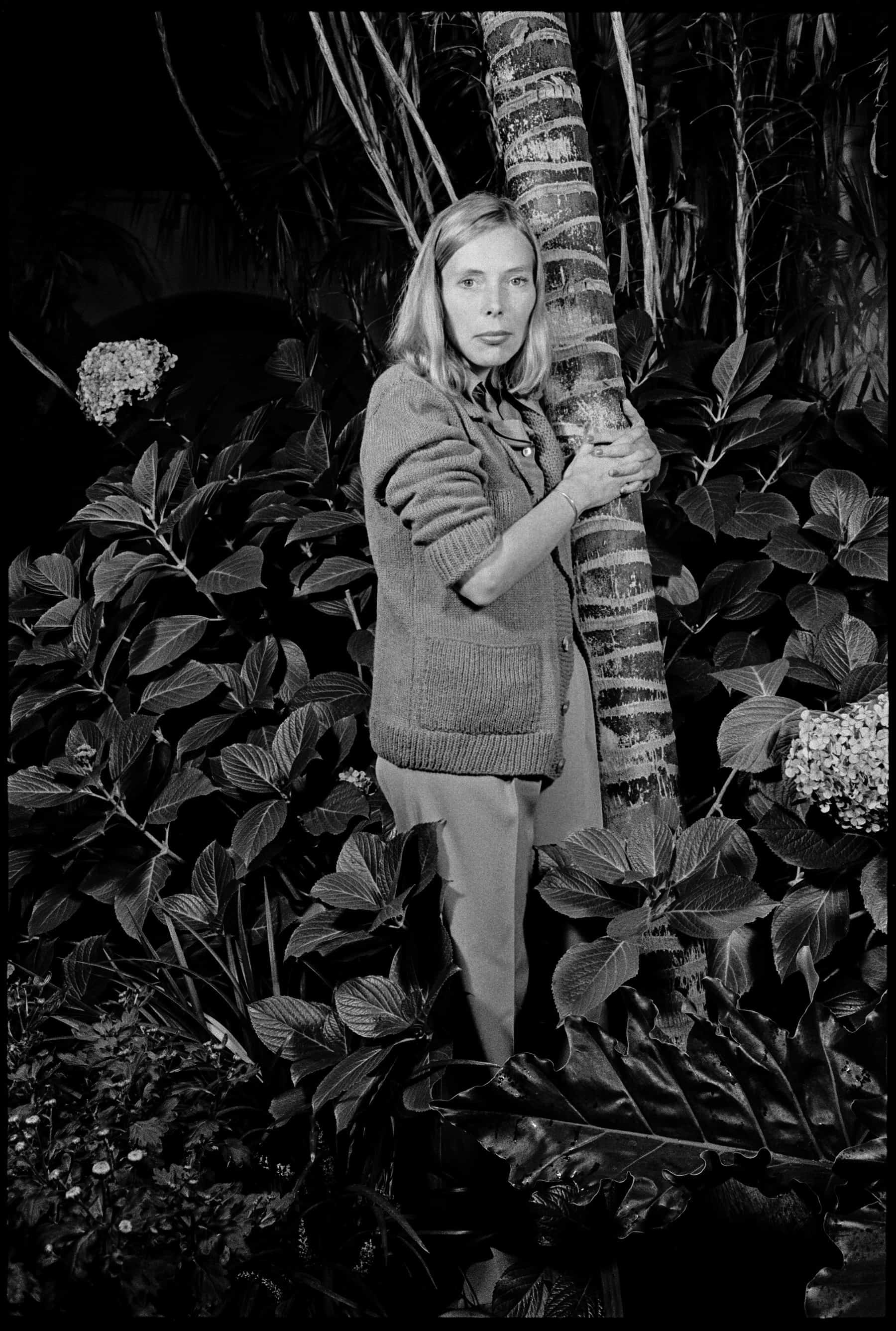

Tell me about the Joni Mitchell shoot.

Jim Brodey and I were pals, he was a mad poet, and a fantastic guy, and he had worked with The Herald, too. Winter was coming hard, and we said, “Let’s get out of here, let’s go to LA.”

“Why don’t we do a story about musicians who are also artists, writers, drawers, whatever.” So we made a list of all the people who we knew happened to paint. Well, she did.

We wanted to hang out with Randy Newman, so we said, “We’ll say he draws.” Commander Cody, Don Van Vliet – Captain Beefheart. We made up this list, and we went to Esquire and said, “We want to do this story” and they said, “Okay, great!” They paid for the whole trip.

How long were you shooting with Joni?

It was just a day.

Joni Mitchell, 1975

JUST a day!?! You mean you spent all day with her?

I guess we got there around 3 o’clock, something like that, and we left at around midnight.

That shot was in the backyard.

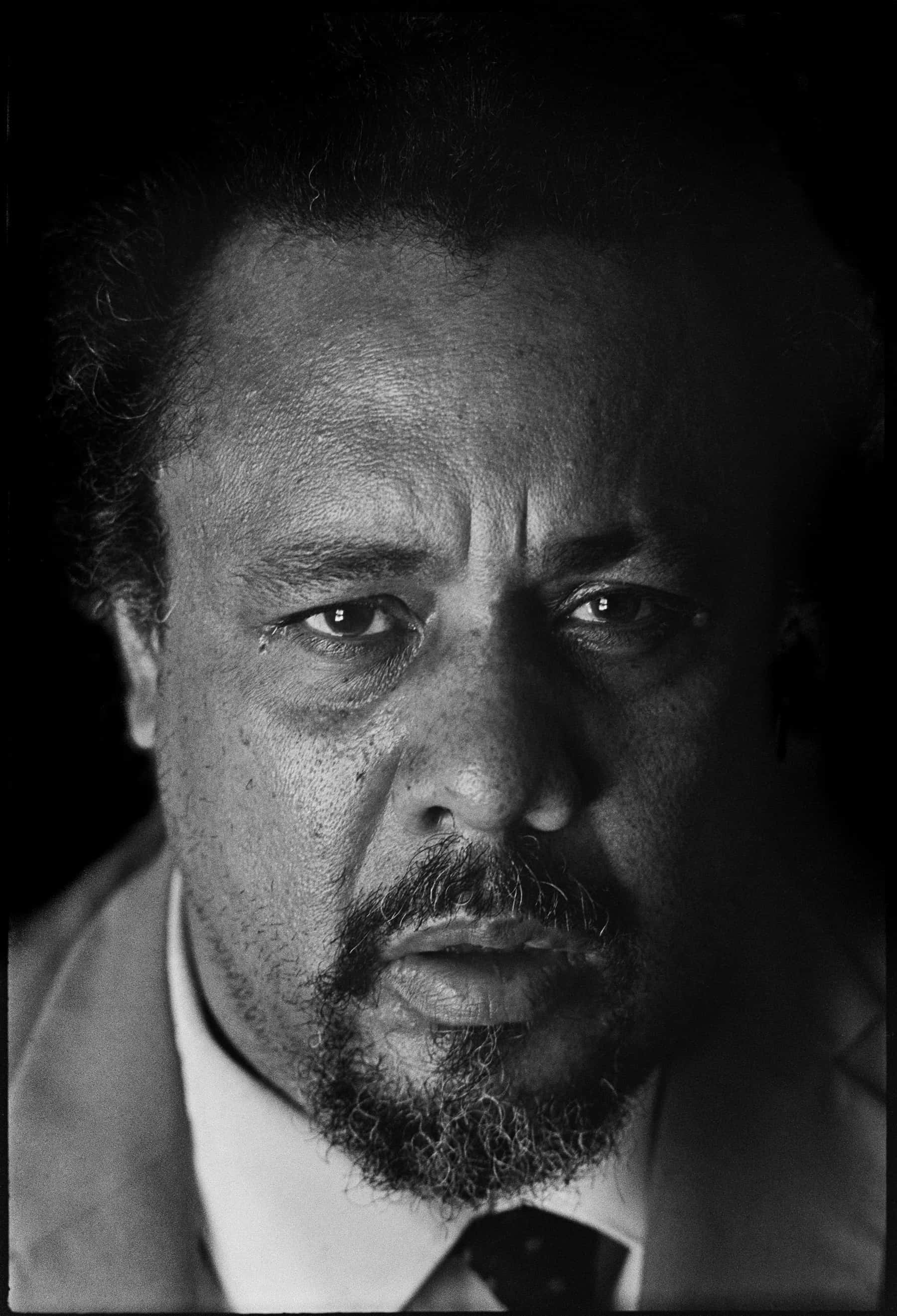

Here’s a good transition: Charles Mingus. That was at his home, right?

Yeah. He was living with a woman named Sue Graham. And I got there, it was so funny, she had him all dressed up.

It was sweltering afternoon in the summer of 1970. He’s all dressed up, in his tie and everything, and sitting there like a kid waiting for his portrait. I was amazed that she let me do it in his shape, because when I got there, it was clear that he was nodding out from the medication, must have been some sort of downers.

Charles Mingus, 1970

Every once in a while I would say something and he’d laugh or something like that, but it was very painful to shoot, for me, because I was dealing with somebody who obviously was in some sort of distress or pain.

I managed to get this picture that I felt was strong, but otherwise it was a very hard shoot, there’s not one other picture that works.

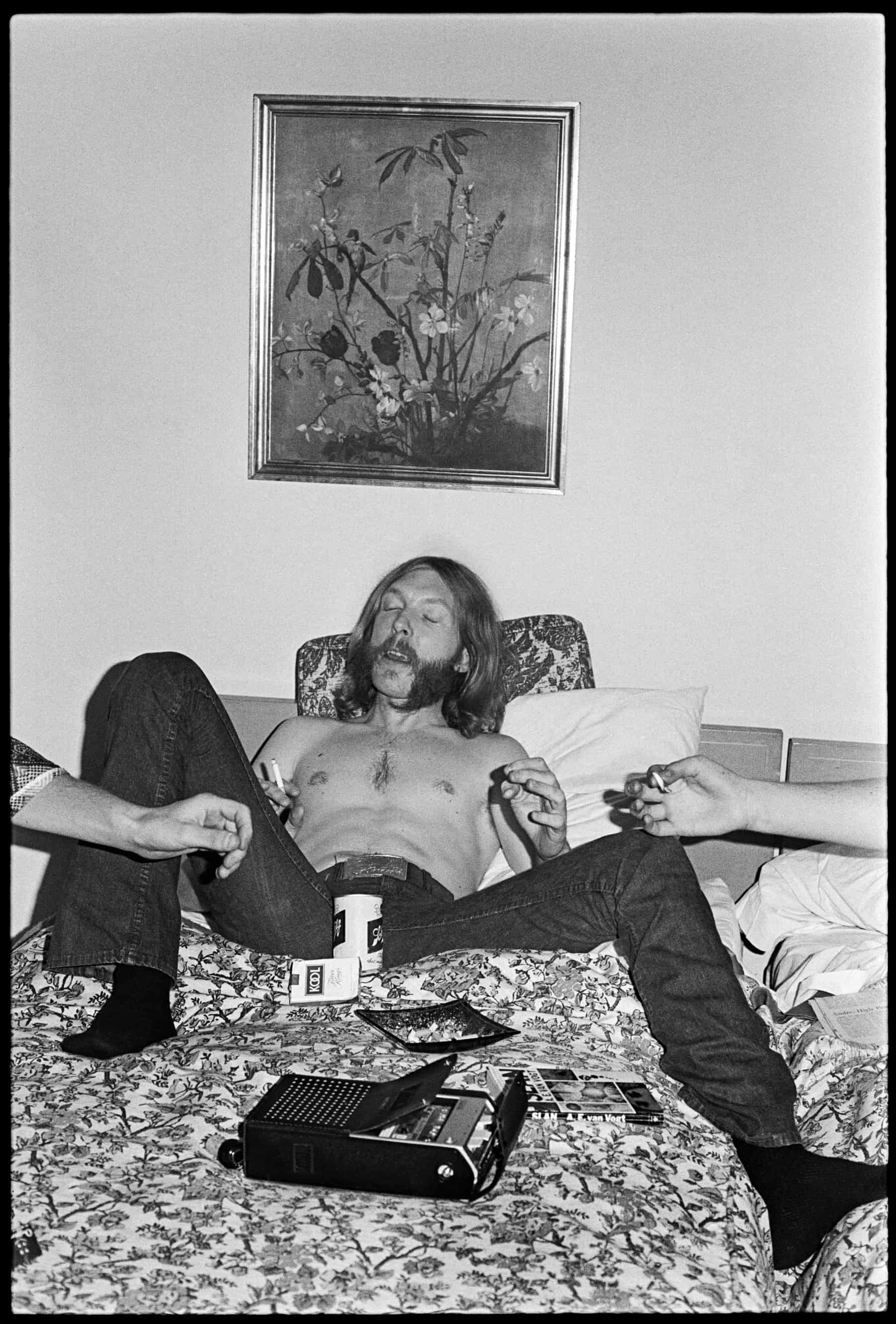

Duane Allman.

They were playing at Fillmore East, it was one of their last concerts.

So we get to Duane’s room in the Chelsea Hotel, he lets us in, and I take pictures of him with his guitar, something like that, and then of course we break out the pot. Gregg shows up, a couple other guys from the band, so we’re all sitting around smoking dope, and I got that shot.

Duane Allman, 1971

What I love about it is, apart from the two hands reaching for the joint is the science fiction novel, the old tape player. It’s all there.

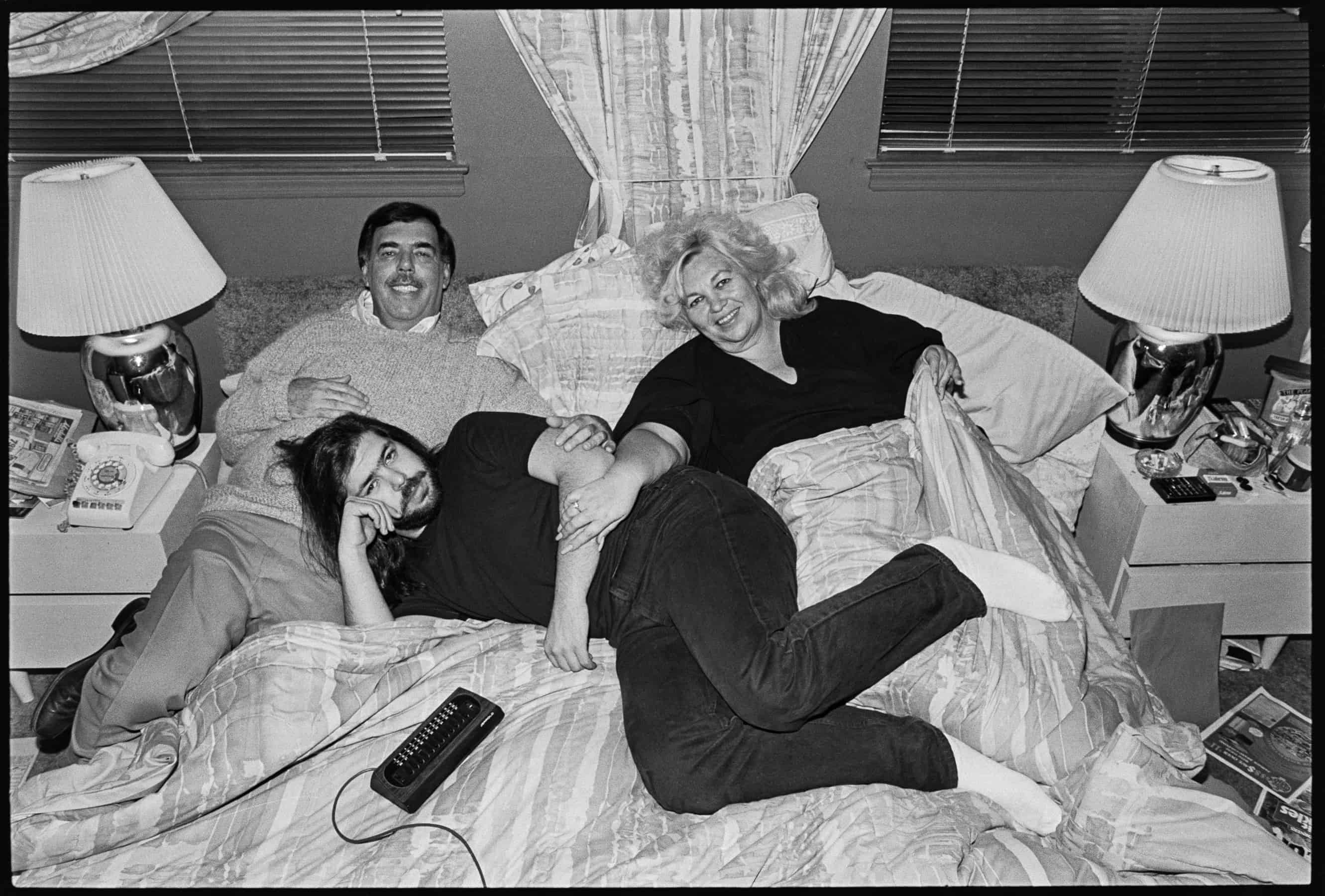

Rick Rubin with his parents.

That was for The Voice, and it was like, “Spend a few days with Rick Rubin,” and it was great, we had a ball. He loved White Castle hamburgers, so we binged on White Castle, and drove all around, photographed him at his studio, stuff like that. But then, we more or less go out to see his parents’ house.

Rick Ruben, 1986

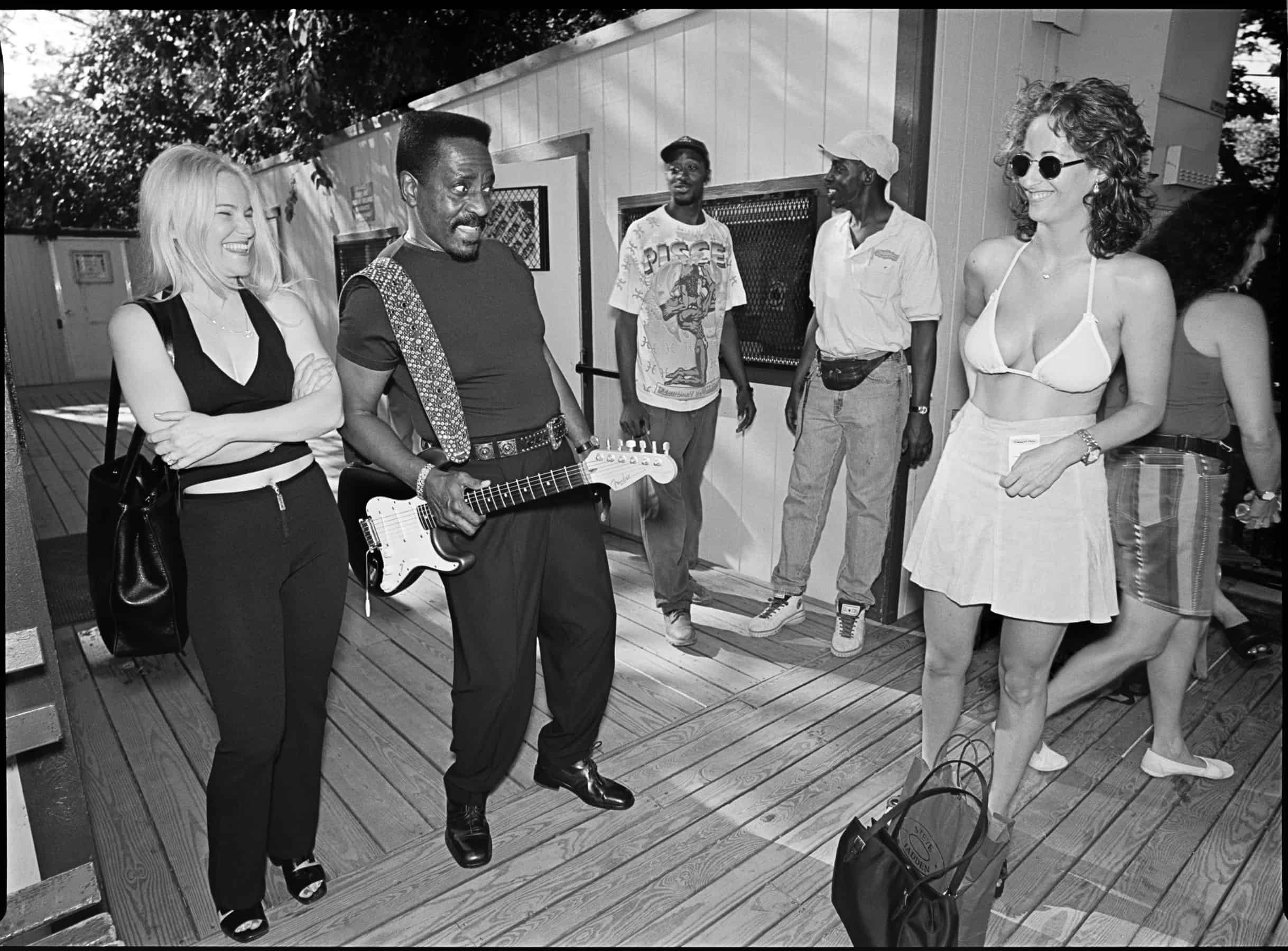

Ike Turner.

Eva didn’t even want that picture in the book.

Oh! Why?

I had to kind of fight for it. I don’t know why.

Ike Turner, 1997

I think it’s a great picture. This was backstage, he was performing with SummerStage in Central Park. This is his wife, his girl, I like the way she’s digging him, and he’s digging her.

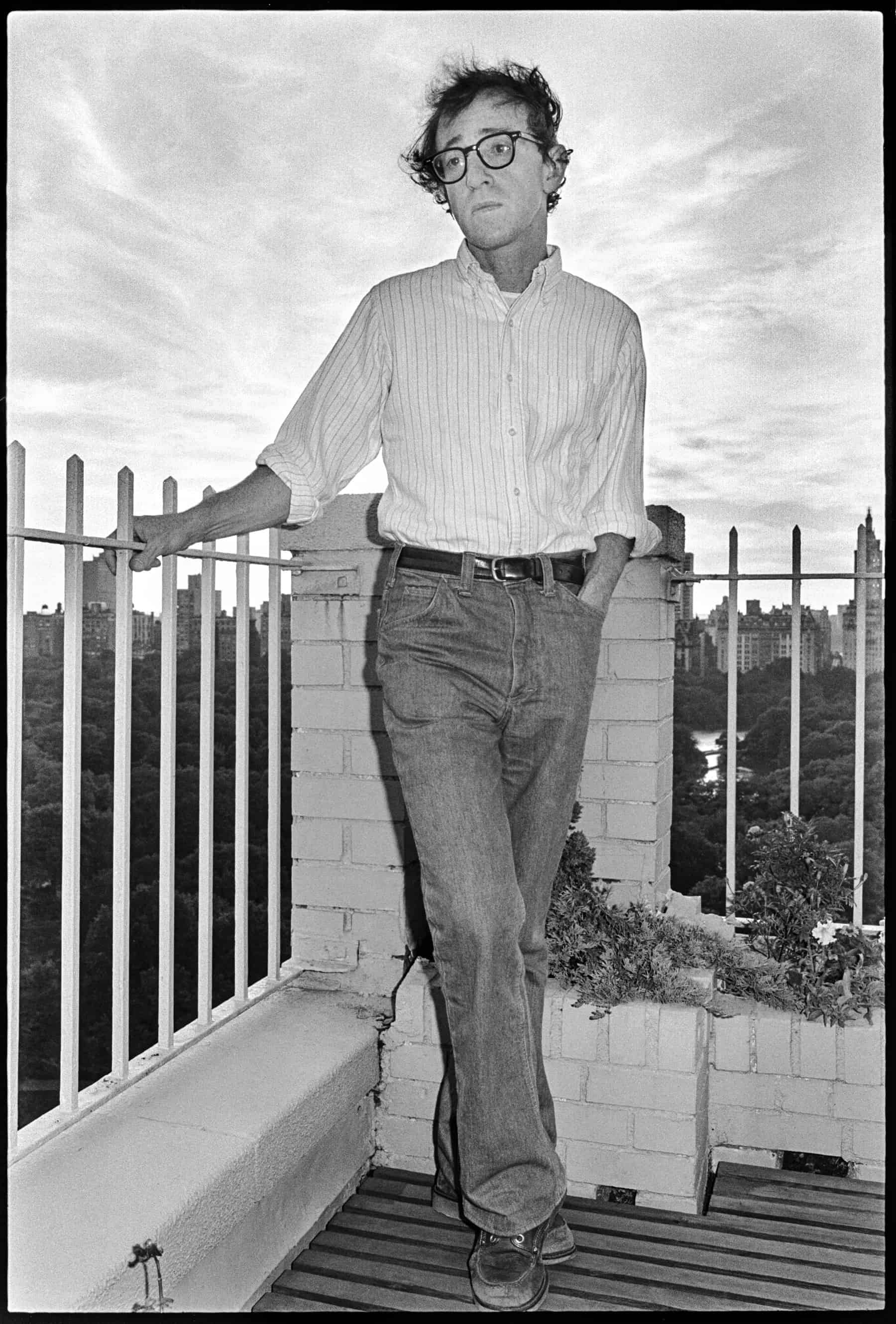

Woody Allen.

You know, Woody said I’ll give you 5 minutes, so the article is titled “5 Minutes With Woody Allen.”

Both you and the writer shared the 5 minutes?

I just grabbed a couple pictures at the end.

Woody Allen, 1979

John Denver. There’s something with the picture that has a kind of like…

…it’s kind of sad.

It’s kind of sad, but it also has the look of an in-between shot.

Exactly, it was the in-between. I felt that, too. But I liked it for that reason. I liked it because he’s, he was on tour…

You were starting shooting seriously in the early Seventies, and you only stopped shooting regularly a few years ago; that’s amazing.

Well, when I got run over. (laughter)

I know, that’s exactly what happened!

And you had a reporter with you to take detailed notes! But you’re still shooting. What do you shoot? How do you shoot?

Nowadays I’m just shooting whatever I come across. I don’t do portraits.

If someone came to you with an assignment, would you take it?

They have, and I haven’t. Mostly what I get called about, somebody called me from the Boston Globe the other day, but it was just because I happened to be on their list and they had called six other people. Most people don’t think I’m in the game anymore, which I’m really not.

But I was getting calls for all the time when I was laid up was movies, stills in movies, and I couldn’t do them because I couldn’t walk.

You’re pretty mobile now.

Oh yeah I could do it now, but it’s such a grind, and the hours…

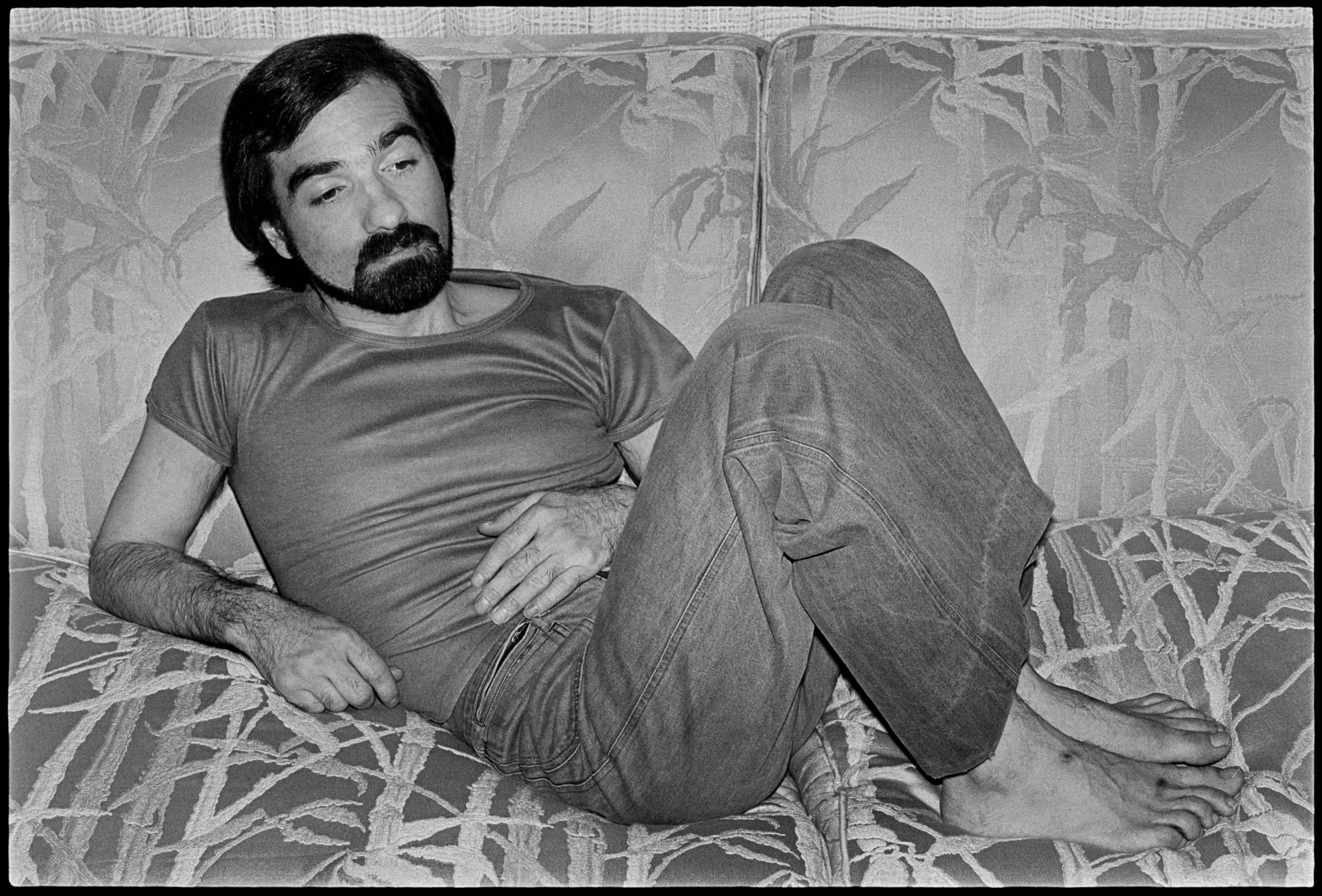

So why did you do it? It seems like, given the excitement of the work you’ve done on staff, it seems like doing stills on movies would be so boring.

I’ll tell you why I did it, because A) I would be working with people I liked and knew and had fun with, B) I made a documentary about it, I shot more backstage; the drag of doing that gig is that they want you to get what the camera gets, and nowadays, especially with digital, why the fuck can’t you pull frames from the movie for God’s sake. But it’s a union job, so somebody’s always got to be there, but I would make it a documentary, the making of a movie, that was my game, to make it more interesting to me. Otherwise, forget it.

It was good to keep your eye working backstage, catching things, it’s good training. But the copying of the movie is the dumbest thing.

top: Martin Scorsese, 1978 below: Jack Nicholson, 1975

You work with Wes Anderson, and he’s super color! Is that a problem for you?

No, I mean, I can adapt. You know, I work with color but I don’t love it.

Have you learned anything from working with directors like Wes? He’s so visual.

Oh yeah, but I think we have a lot in common, it’s kind of a direct method. He likes master shots, and I like master shots. I love working with him because I admire what he does. Whether you like his stuff or not, God knows he gets what he wants.

I’ve always liked deliberate artists, especially film makers, I mean, Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick. Bunuel makes it all deliberate.

So what books do you have planned right now? Do you have a timeline?

Not really, right now I’m just collecting street pictures from my life, collecting, eventually printing, it’s going to cost me a lot of ink. I quit drinking and that’s where I spend my money now (laughter). I quit booze for ink!

Sure.

New York landscapes, I have tons of those, without people. Because I was always respite to get away from people, do landscapes. And portraits, I guess, but they could be divided into so many categories. Thurston wants to do a book on my poets and writers.

Yeah. I think a Greatest Hits one is a good idea. A Greatest Hits monograph.

I do, too, but God. It’s huge! Wes is constantly saying, “What can I do? What can I do? What can I do?”

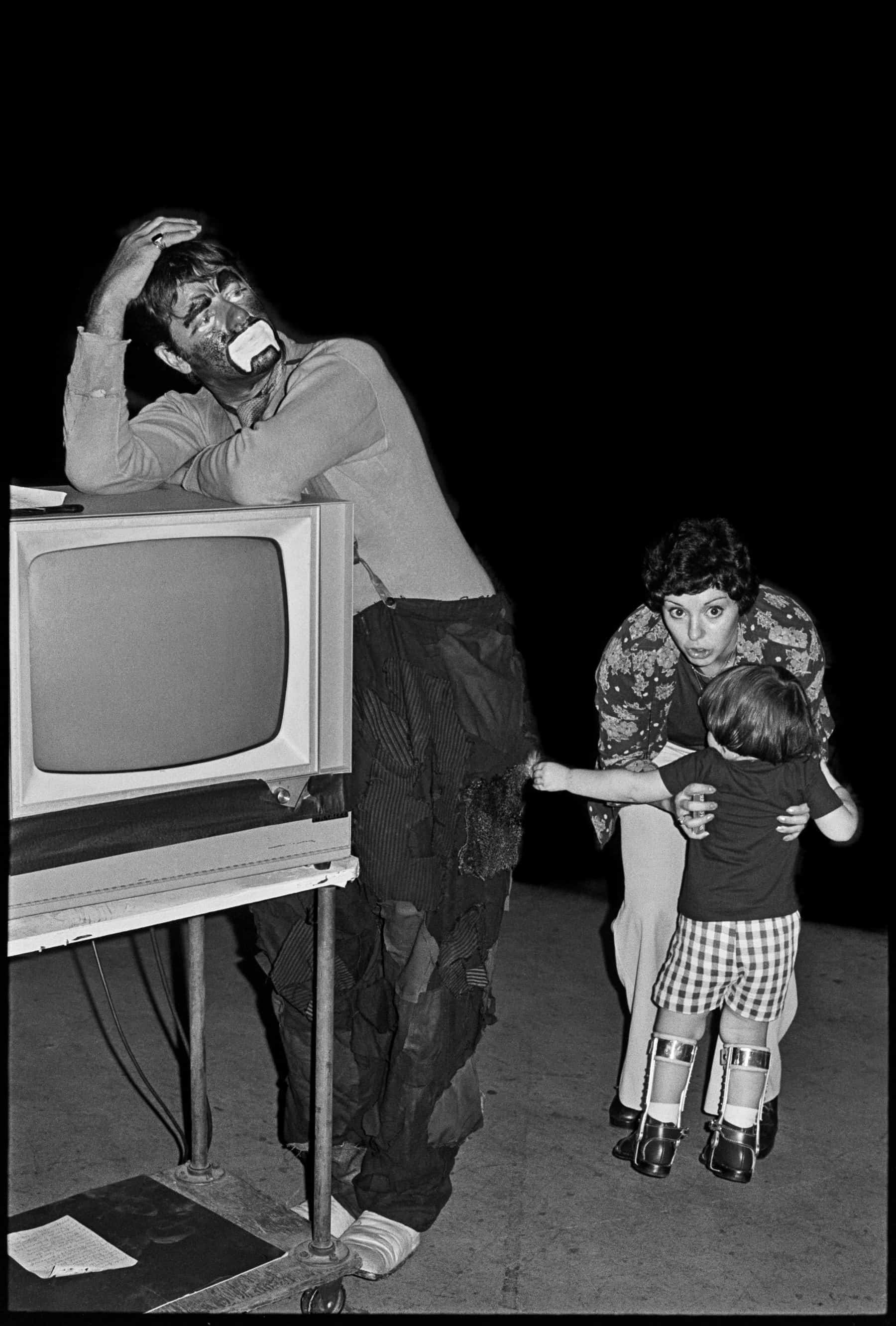

I love that Jerry Lewis picture, what’s the story behind that?

Again, that’s from my mother. Jerry Lewis was doing a promo for muscular dystrophy. I didn’t set that up – it looks like I did – he’s leaning on a TV, and there’s this sort of stage mother with her paralyzed kid.

That could be the cover of the book.

That’s what Wes said!

Jerry’s whole story comes through that picture. It feels like the ultimate Jerry Lewis picture.

It’s full of his sort of self-regard, and his maudlin nature.

And yet, but it seems genuinely sad and lonely, too.

And all of that, and absolutely all of that, but it’s got some of the other, too, and it wouldn’t be the picture, obviously, without the kid and the woman.

Of course it makes it darker. Wes, at one point did say, “That could be the cover,” and I said, “Maybe the back cover.”

Jerry Lewis, 1975

Is there a way you define your style, or your philosophical approach to shooting? Because it’s subtle, but it’s there.

I hope that there’s some sort of penetration, that I’m penetrating.

What’s this gesture you’re doing?

Trying to get in there, you know…

(whispering) He’s turning his wrist like a screwdriver.

(chuckles) I’m really trying to get something out of them, and at the same time, impose my sense of humor, my sarcasm sometimes, my attitude. I’m trying to impose my point of view, the best pictures look like mine, somehow, and sometimes it’s indefinable. But there is an edge to a lot of them that I think is my edge, I think I own that.

top: Jackie Chan, 1987 below: Nuns on Mountaintop

In 2010 a monograph of James Hamilton’s music photography, You Should Have Heard What I Seen, was published, with Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth as its co-editor and co-publisher. His first book, Pinball! (with color photographs by Hamilton and text by E.P. Dutton) came out in 1977 when this pastime was at it popular peak.