Interview 041 • Mar 7th 2016

- Interview by Lou Noble,

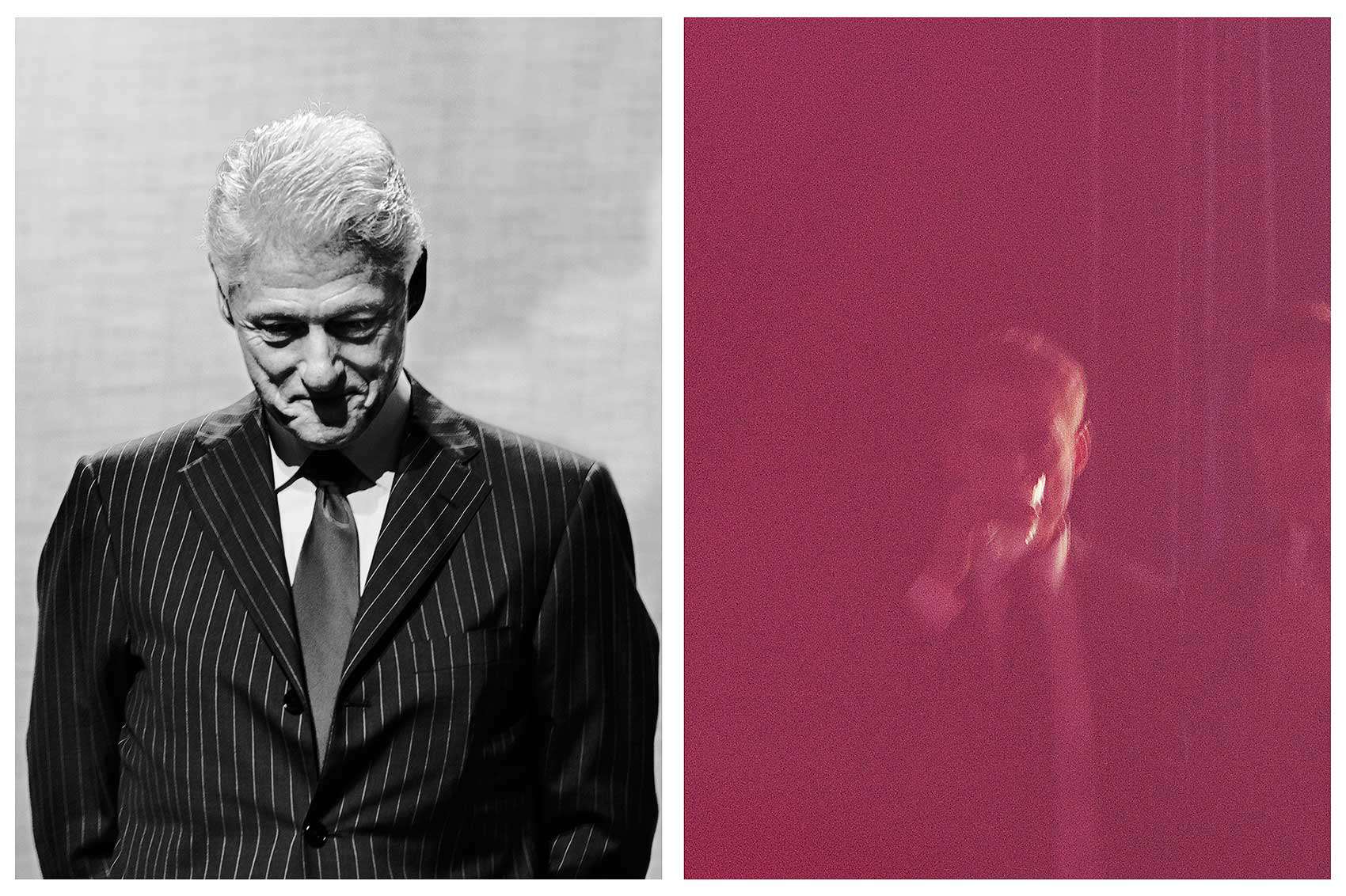

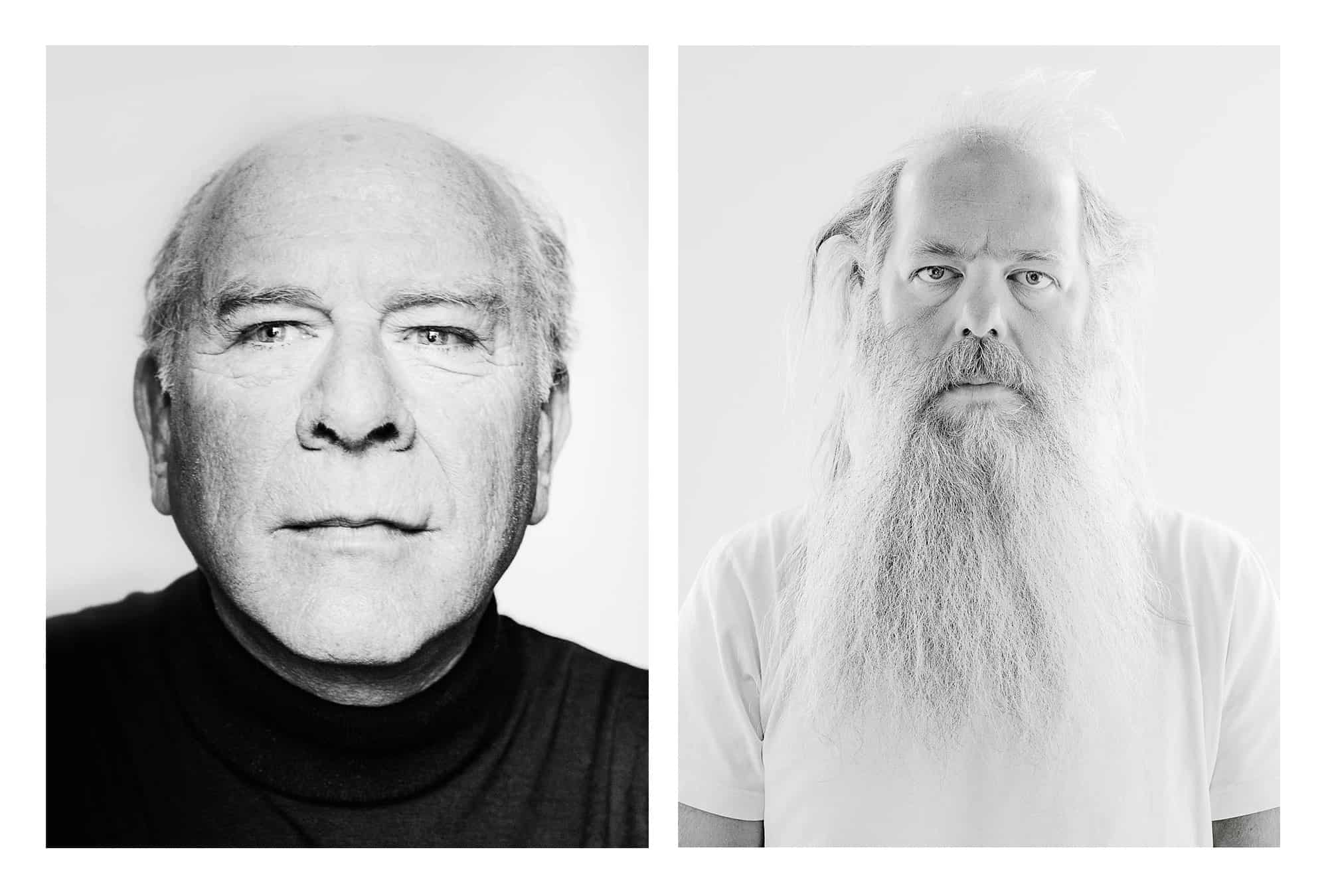

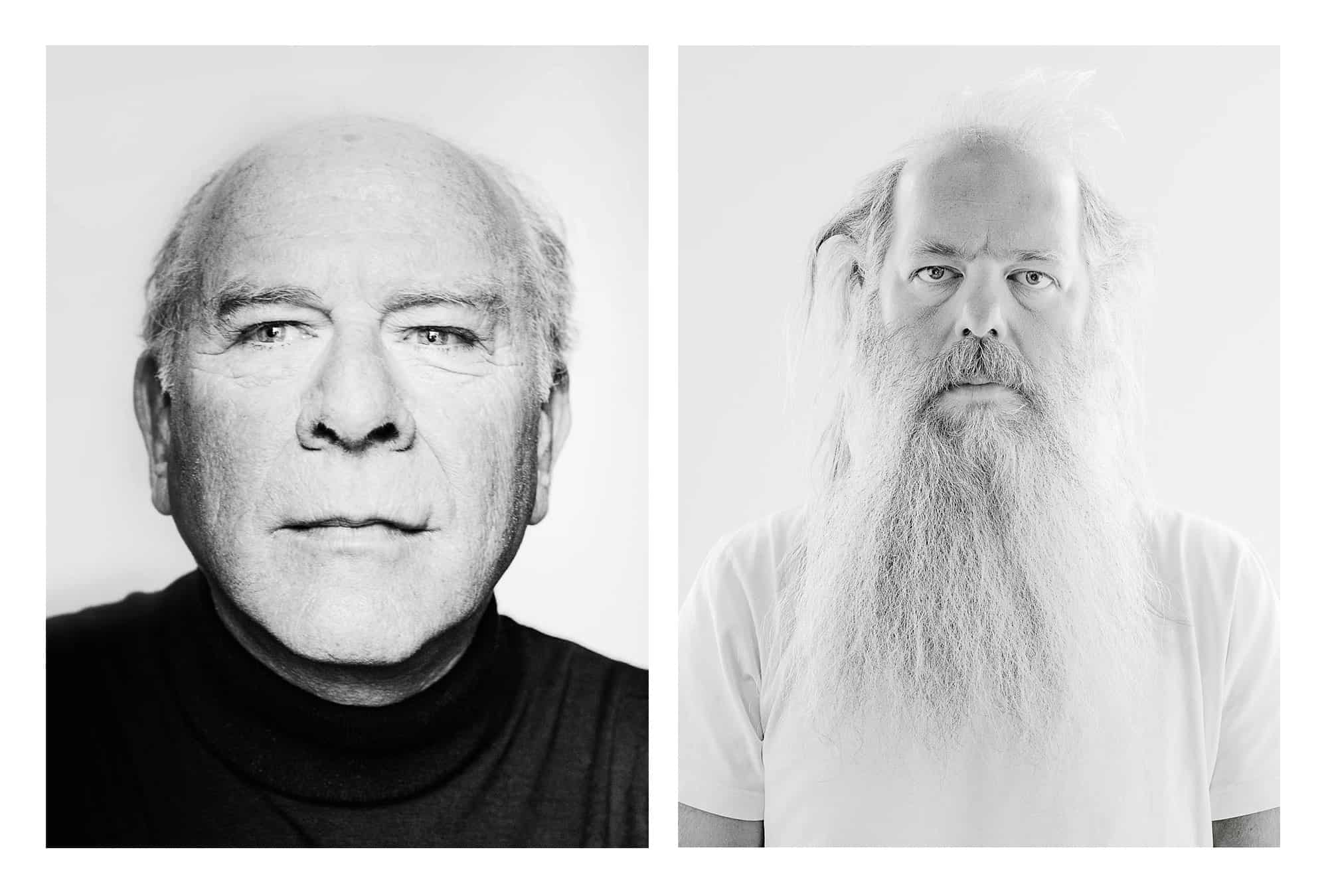

- Christopher Anderson Photographed by Sasha Arutyunova

About Christopher Anderson

Christopher Anderson was born in Canada and grew up in west Texas. He first gained recognition for his pictures in 1999 when he boarded a handmade, wooden boat with Haitian refugees trying to sail to America. The boat, named the Believe In God, sank in the Caribbean. In 2000 the images from that journey would receive the Robert Capa Gold Medal.

Christopher is a member of Magnum Photos and is currently New York Magazine's first ever photographer-in-residence. He is the author of four monographs of photography and most recently coauthored a book with Derek Jeter that will be released in 2014.

Links

Foreword

Lots of interviews are fun, but I especially dig the ones that are rewarding, that I come away with, not just with new knowledge, but with new insight.

Which is exactly how I felt after talking to Christopher Anderson, whose work is both visually stunning and thematically breathtaking. A pleasure, but also a helpful education, our conversation.

This interview has been edited for clarity and content.

Interview

So let me begin by asking you: a few years ago you made the change from “conflict” work, over to portraiture. How did you adjust your style the new subject matter?

I’m not sure that I would say that I converted to portraiture. Now…there’s two things to that. One is that, portraiture, I feel, in a certain sense was always part of my work, even when I was doing “conflict” work. And also, the other side of that is that seems to presume that I think of myself as a portrait photographer solely, now. While yes, I do recognize that there has been a dramatic…I quit doing conflict all together, and there’s been a big shift obviously in sort of the nature of what I do now. But I kind of look at it as a natural extension of what I was always doing.

Mmhm.

I play with different visual languages, I play with a little bit different techniques, the way I make pictures, logistically, has changed a little bit. Sometimes I’m in a studio, I’m choosing the location, I’m controlling the light more, and those things. Those, to me, are all kind of beside the point, external factors that are beside the point. The thing that I’m still looking for in an image is still rooted in the documentary tradition, I think. And I’m still looking for the same heart of the photograph, something that is about an experience and an emotion. The whole idea of it being separated by categories of “was conflict photography, this is now portraiture” to me, makes a false distinction and misses the point.

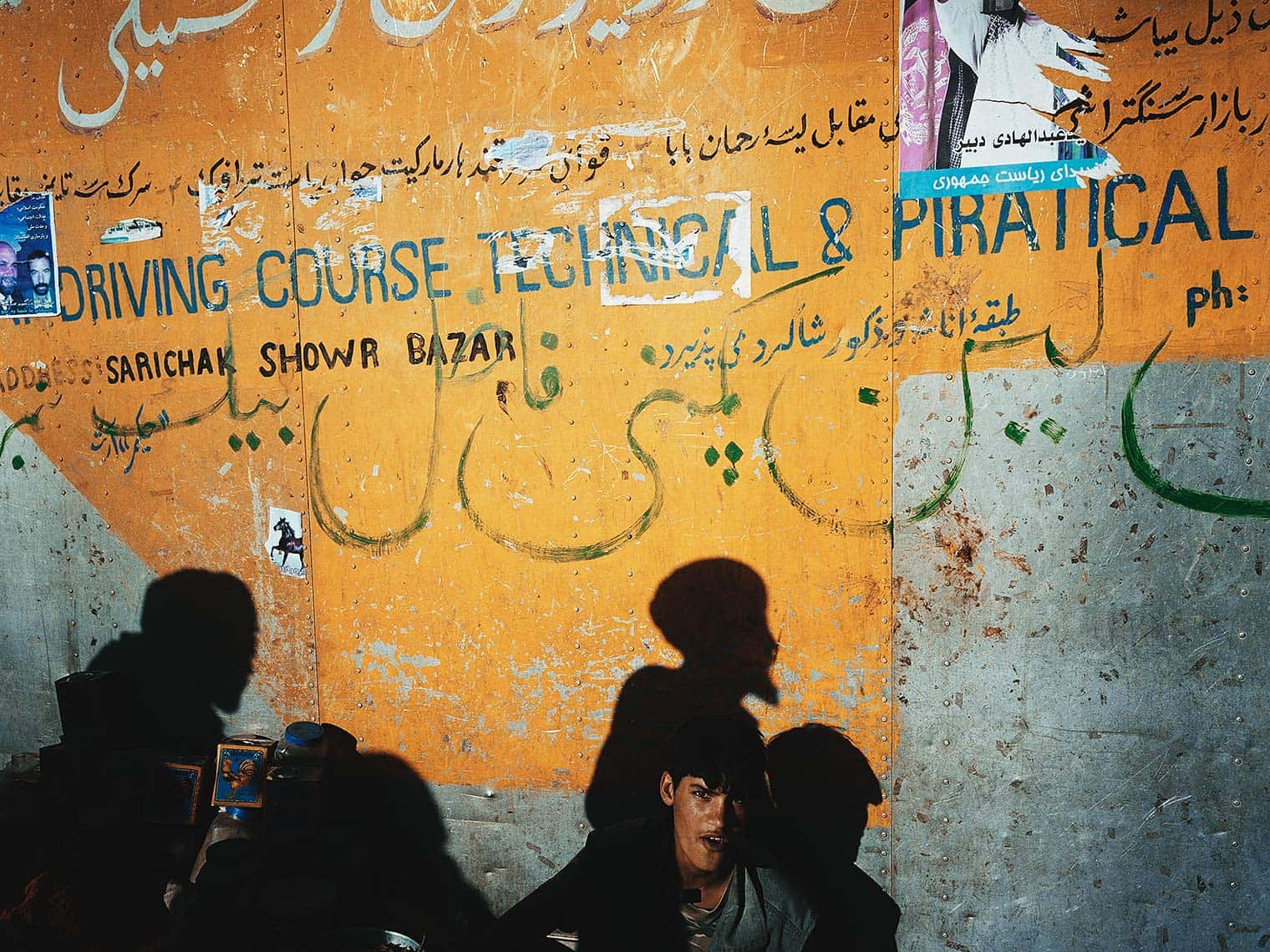

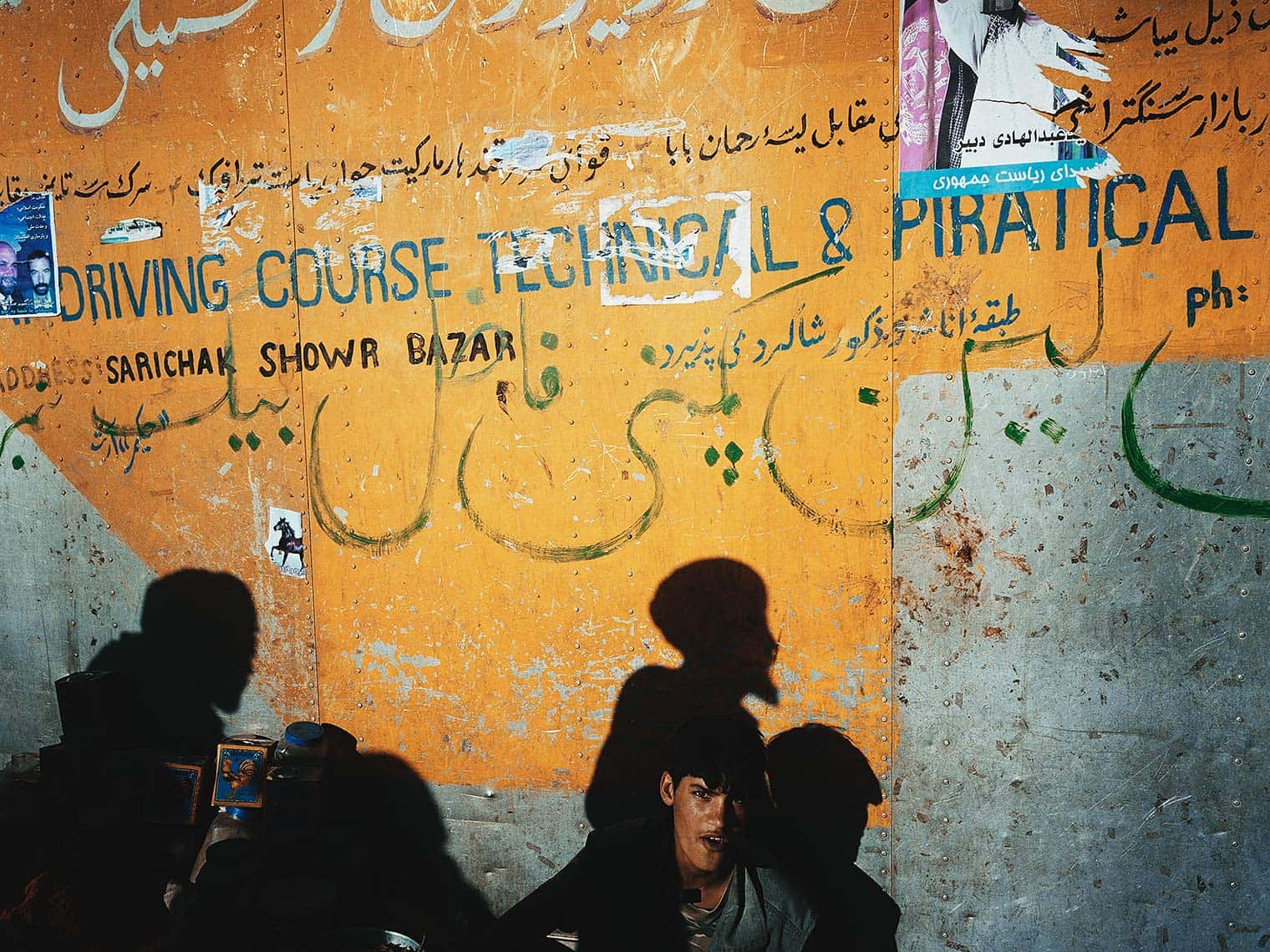

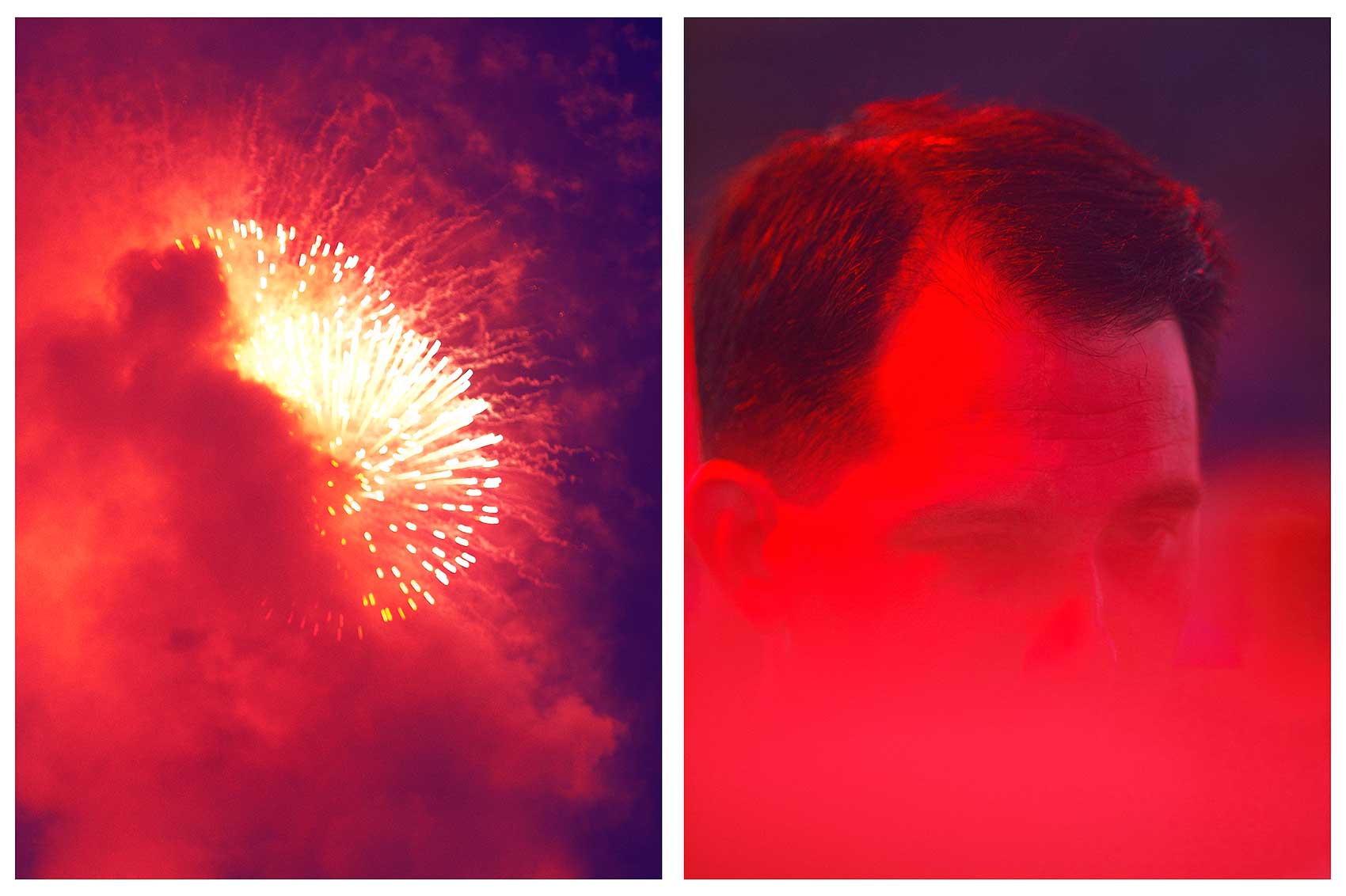

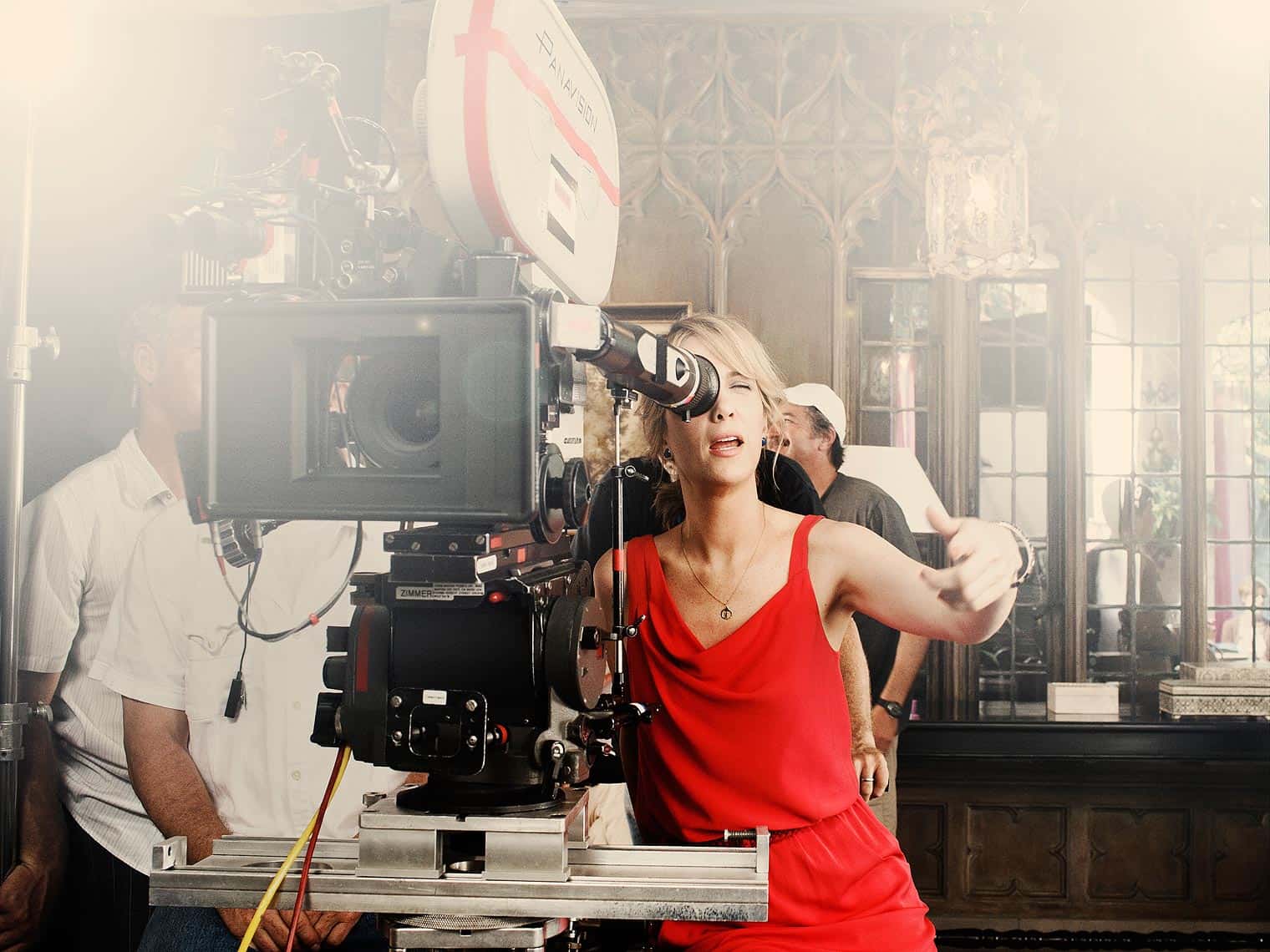

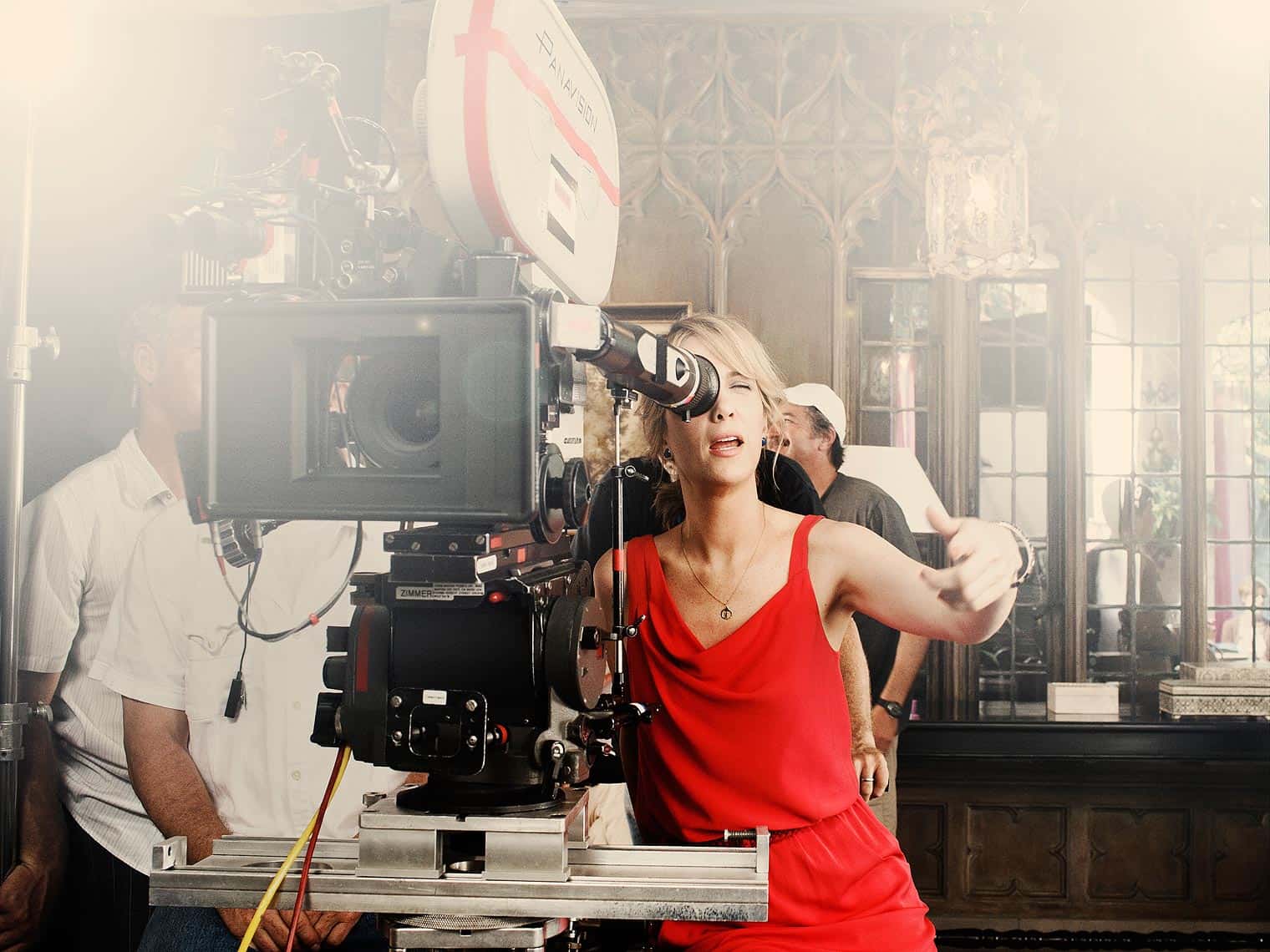

Editorial work from Vanity Fair – Christopher Anderson

Gotcha.

So yeah, what was your original question before I started qualifying it?

Hahahaha, so your target is the same. Do you find that you’re using different tools to achieve that now that you’re in these different environments?

Certainly, yes, I experiment with different tools. Not only different tools, but like I said, the logistical process of how an image gets made changes. If you look at the books that I’ve done, they all kind of use a different visual language.

Right.

Which sometimes is very much tied to a particular tool, or set of tools. But like I said, in my idea of what I’m trying to do with an image, or what I want to say with an image, or what I’m looking for, for that image to do, the most important thing is the essential of what I’m still looking for is something that punches you in the gut. Something that makes you feel something, something that communicates something about an experience that I had or that the subject has. But yeah, I got a set of lights, hahahaha.

Did you enjoy expanding your tool belt?

Yeah, that part of the process has been fun for me. Learning, discovering how to kind of become a technically different photographer, in that sense. That part has kind of been fun in a different way, it’s almost as if it’s another hobby that I’ve got, but it could have been anything. The fact that it was photography is almost beside the point.

Right.

It was fun solving some of those puzzles, and being like, “I wonder how I can make that happen?” Because I had no formal training in photography, so it was all really about feeling my way to a certain thing. I think, very much influenced by my roots as a documentary photographer, as a conflict photographer, even. I still think, even when I’m using artificial light, I’m still trying to find a way to use it, I still see it the way I see natural light, I guess? Even in most of the “lit” photography that I’ve done, a lot of it incorporates natural light.

Do you, as a photographer who is self-taught, do you have a…way you go about learning new processes or studying other photographers?

I don’t know if I could boil it down into a way that I do it, I’m sure there must be, but I’m not really aware of it. I’m constantly experimenting, I guess, with both tools and ways of using those tools. And yeah, I think in my work, my influences are not hidden at all, my influences are pretty obvious. So there are photographers that I look at, that I learn and gain inspiration from, and that has changed, the photographers that I look at has obviously changed as my photography has changed, in that sense. 15 years ago, I probably didn’t even understand why Richard Avedon was interesting, you know? Much less had any desire to look at it.

Right.

And it wasn’t until I started trying to photograph people in the studio, especially more than one person at a time, that I started thinking, “wow.” I had developed an appreciation for what a photographer like that does. And of course, I look at other kinds of photography with a new eye, which, that’s also fun, too, to discover new photographers that I wouldn’t have paid attention to before because it wasn’t the thing that I did. So I expanded my view of what interesting photography is, perhaps.

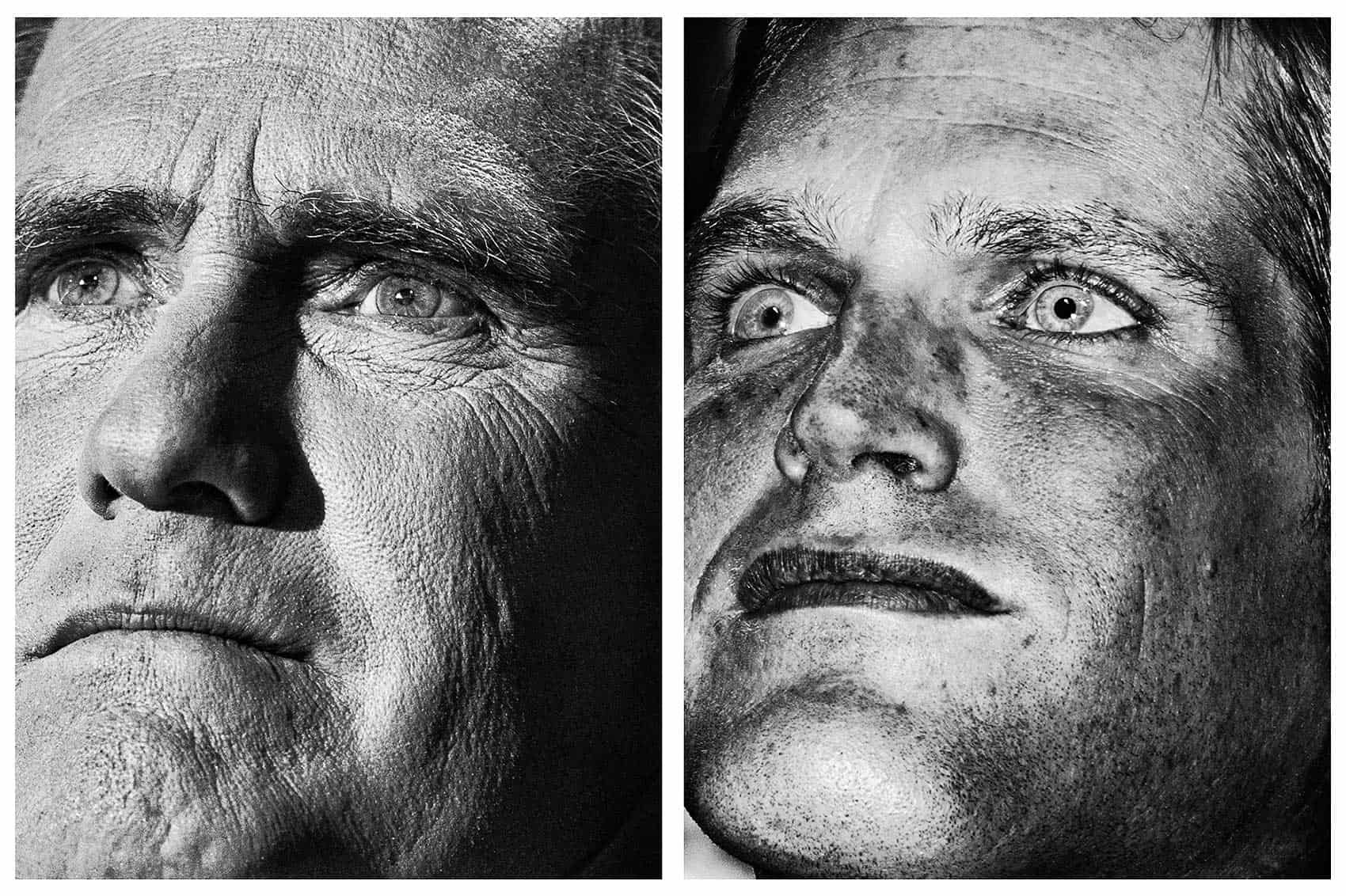

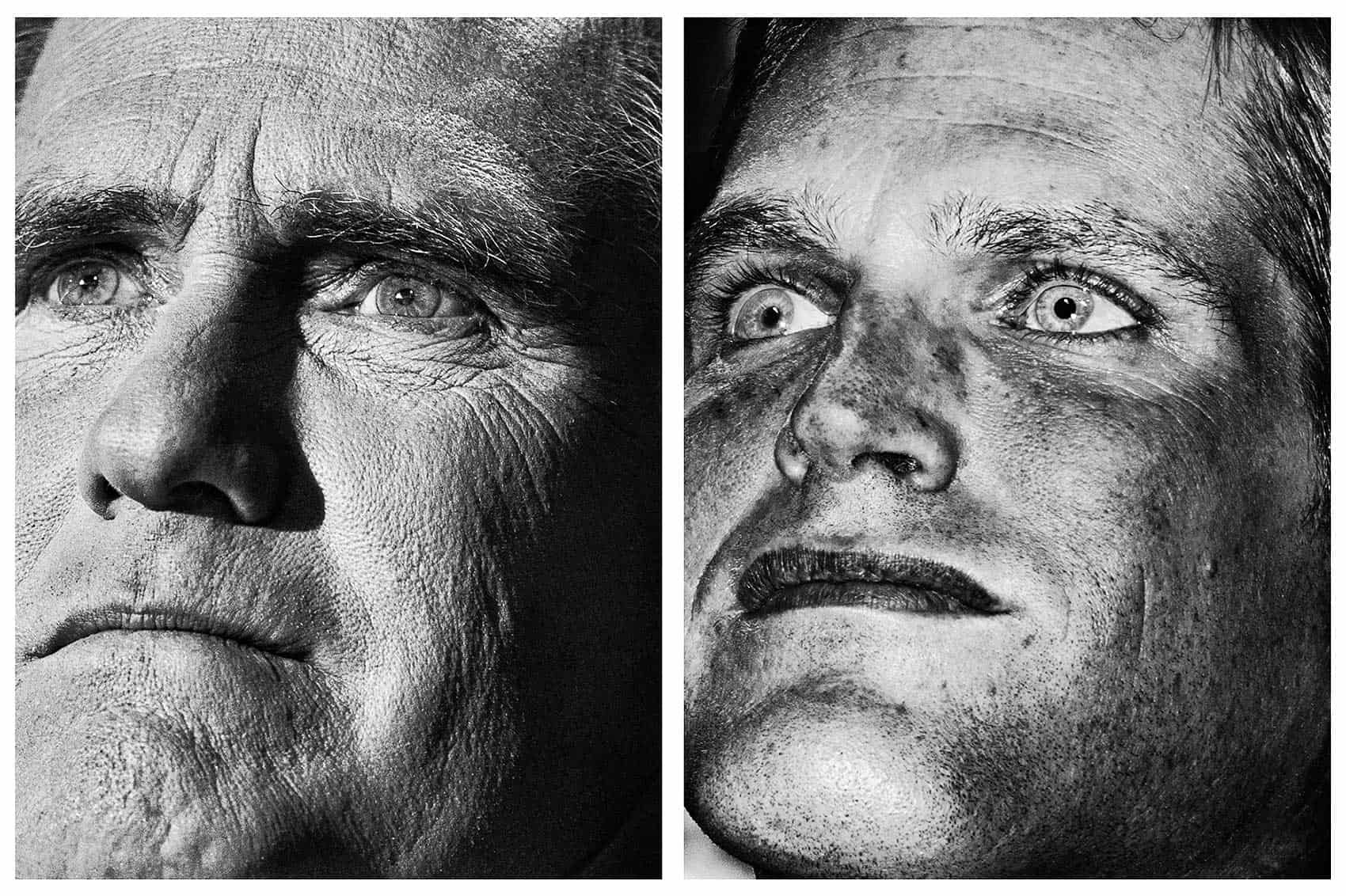

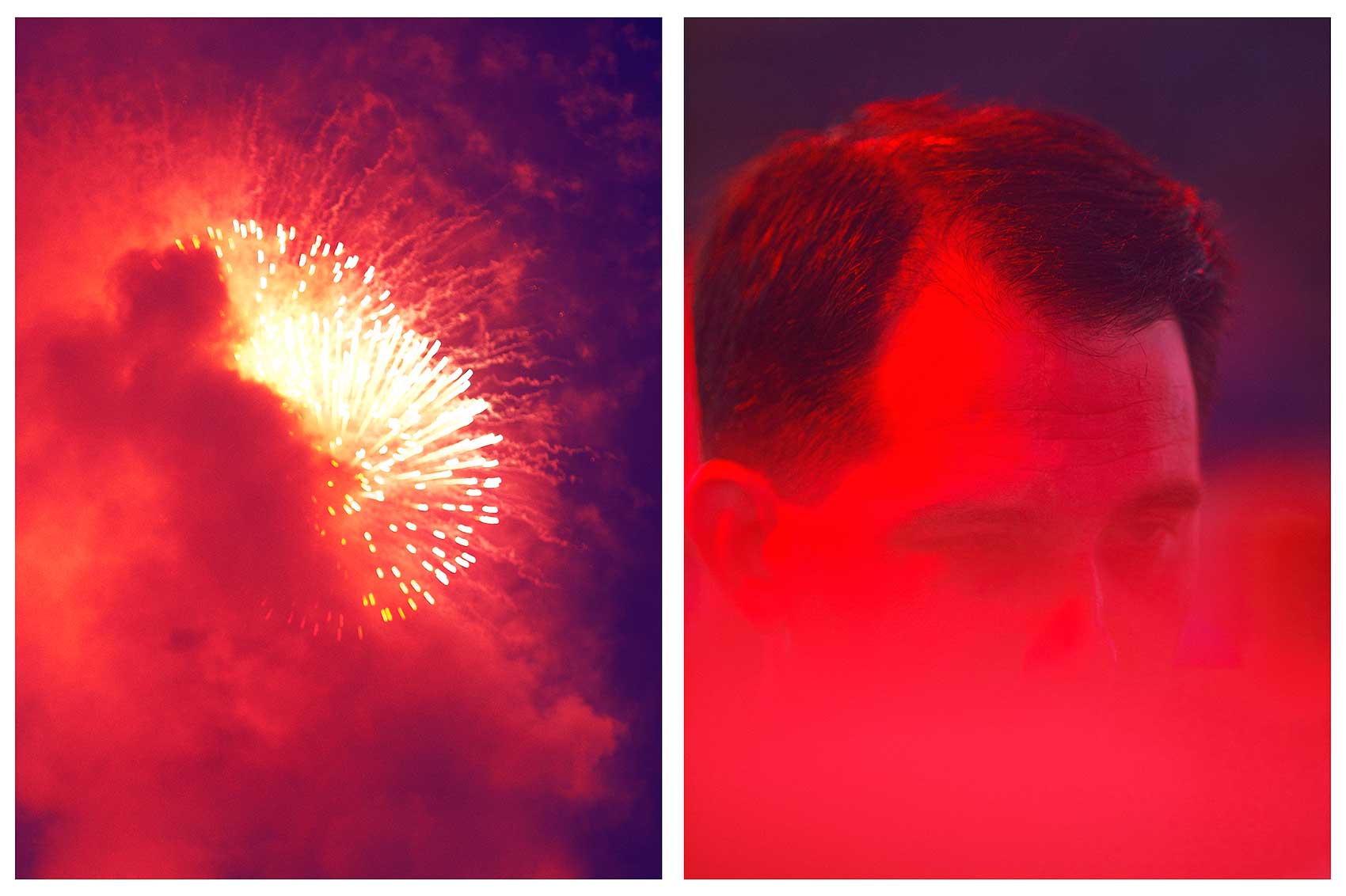

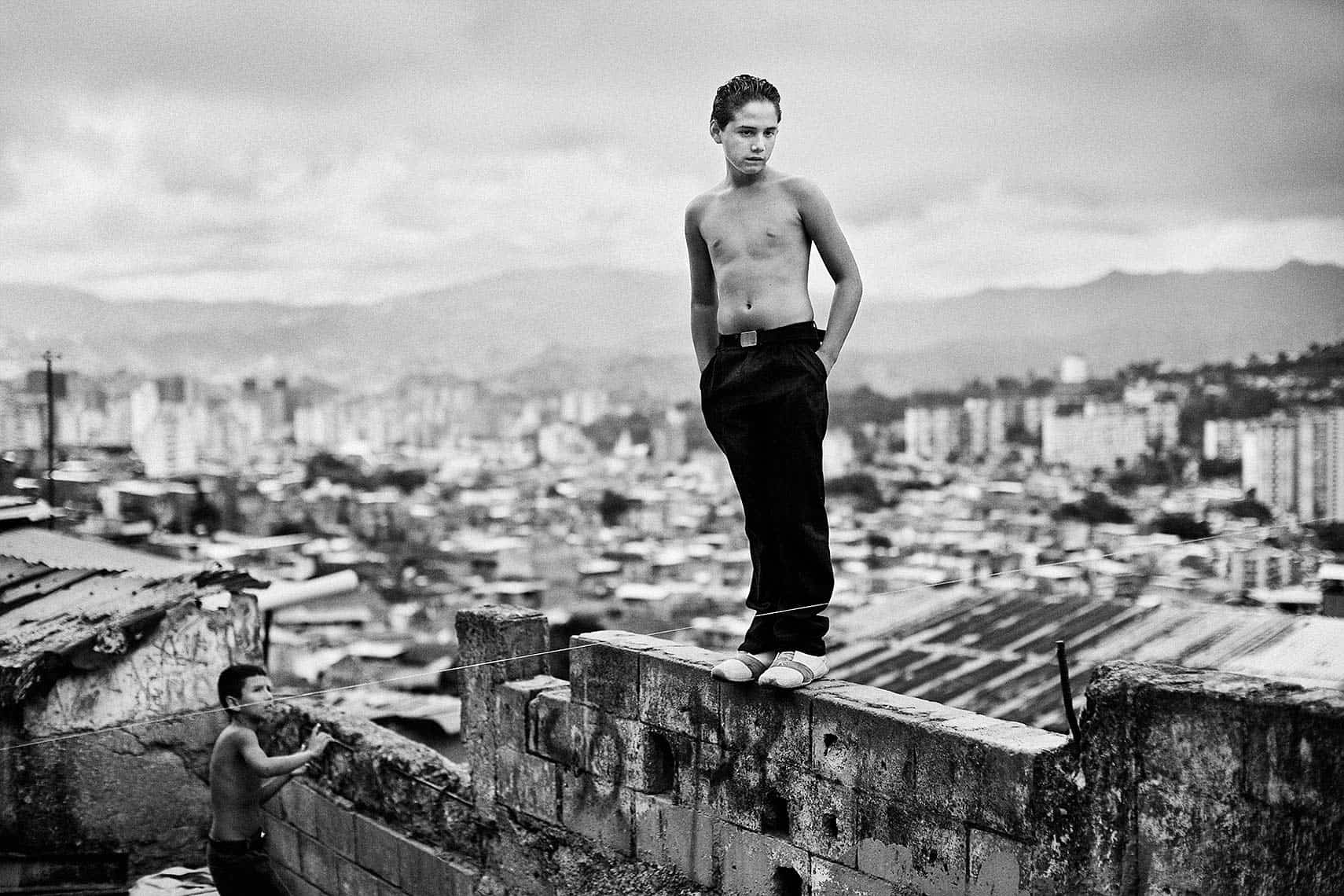

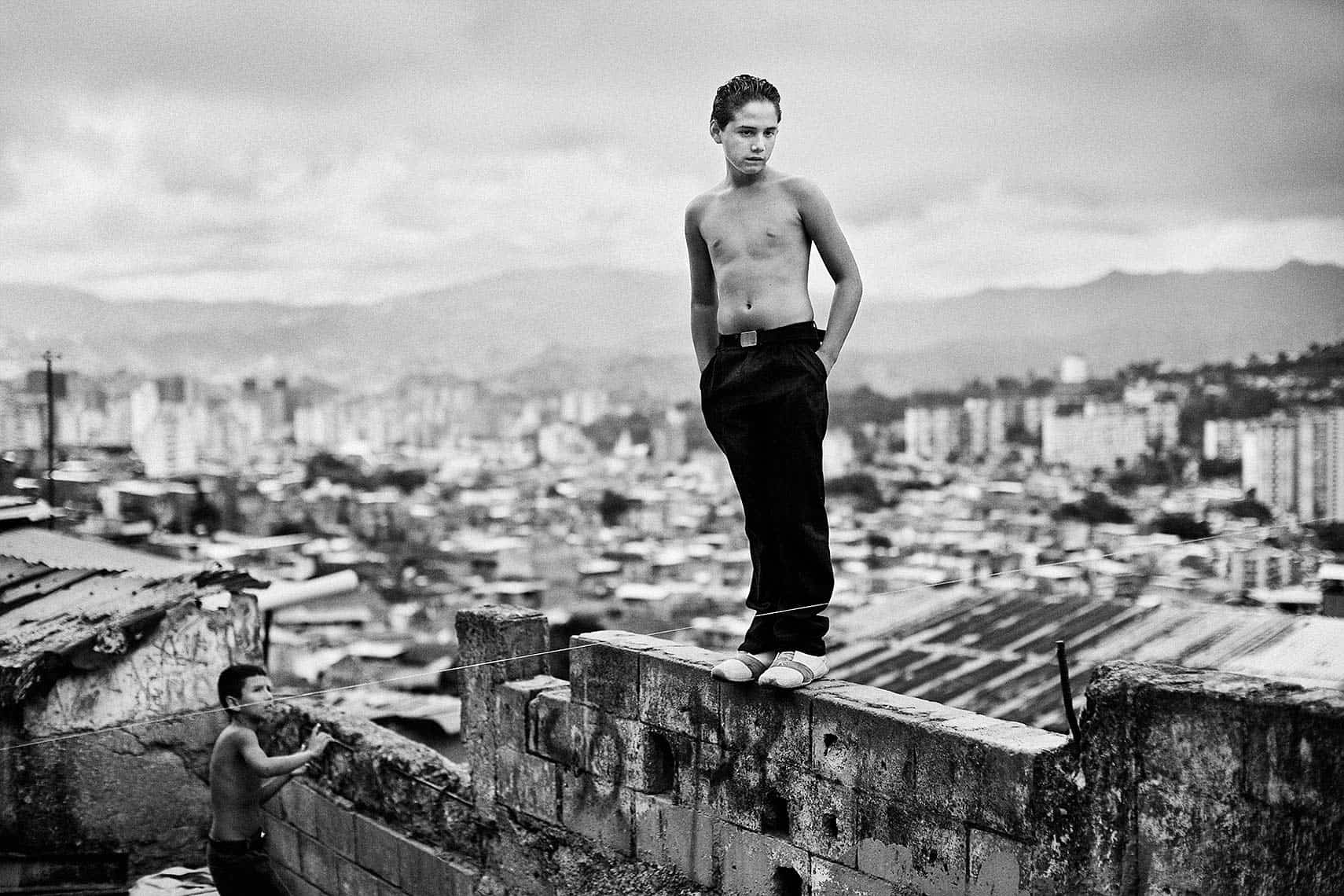

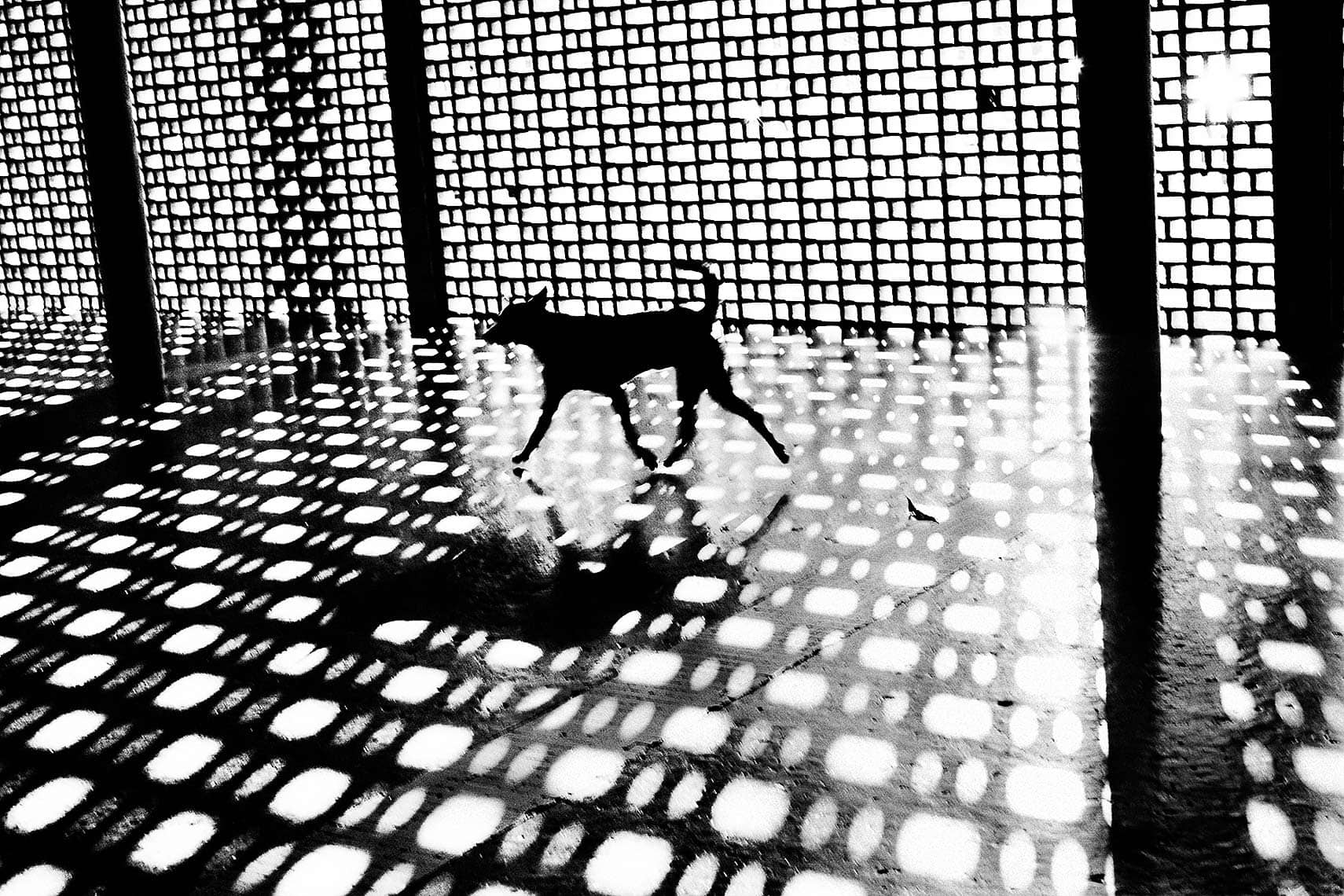

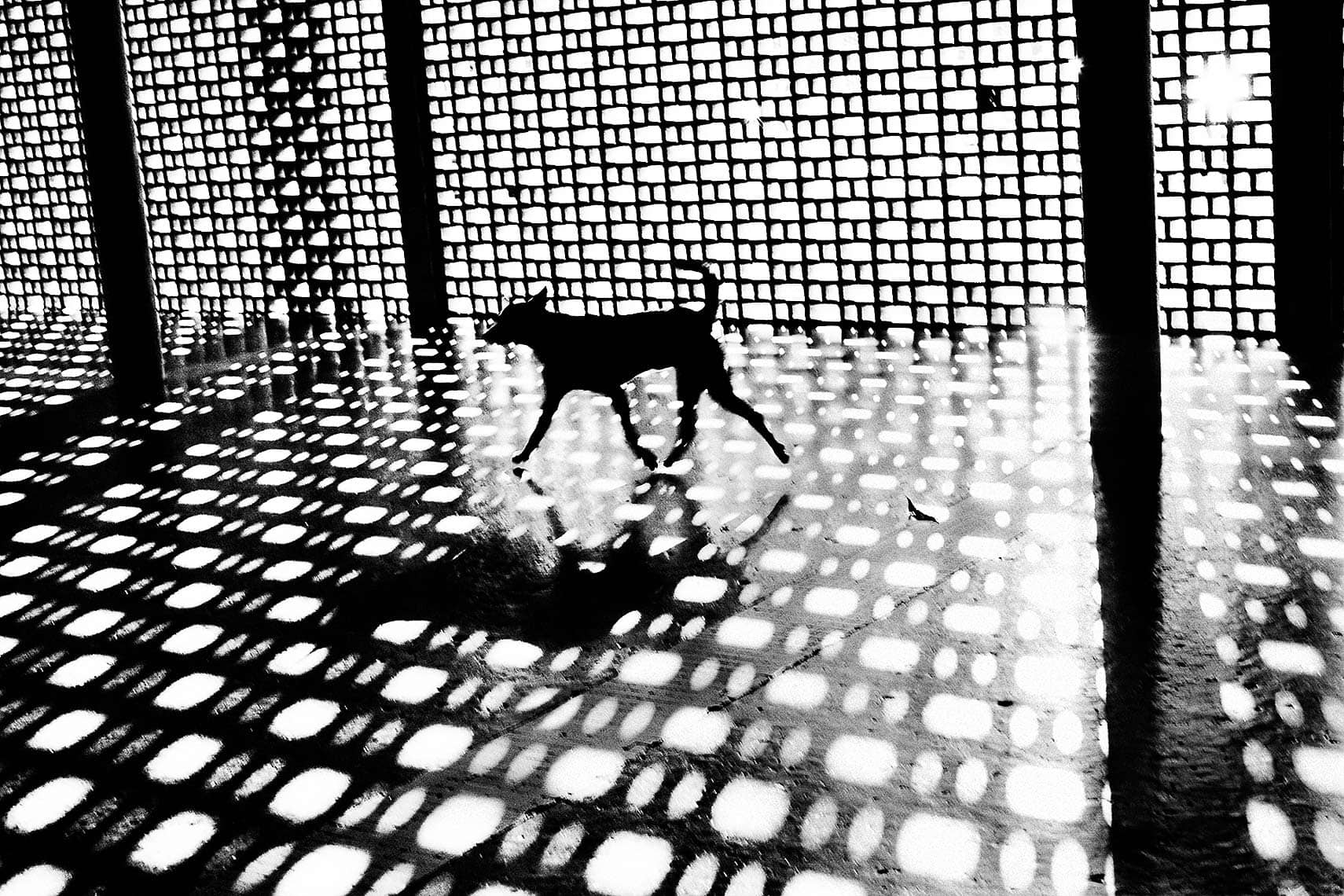

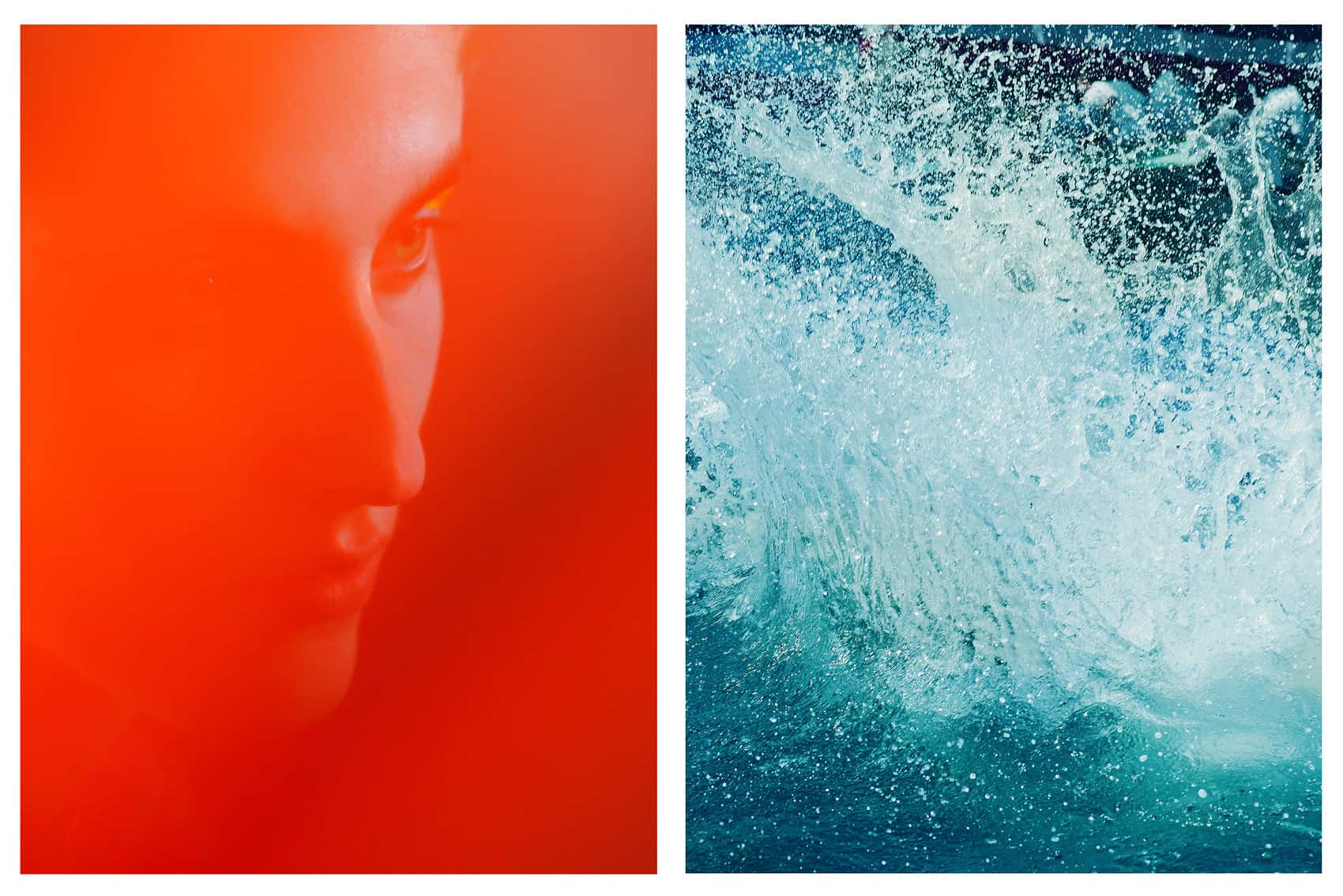

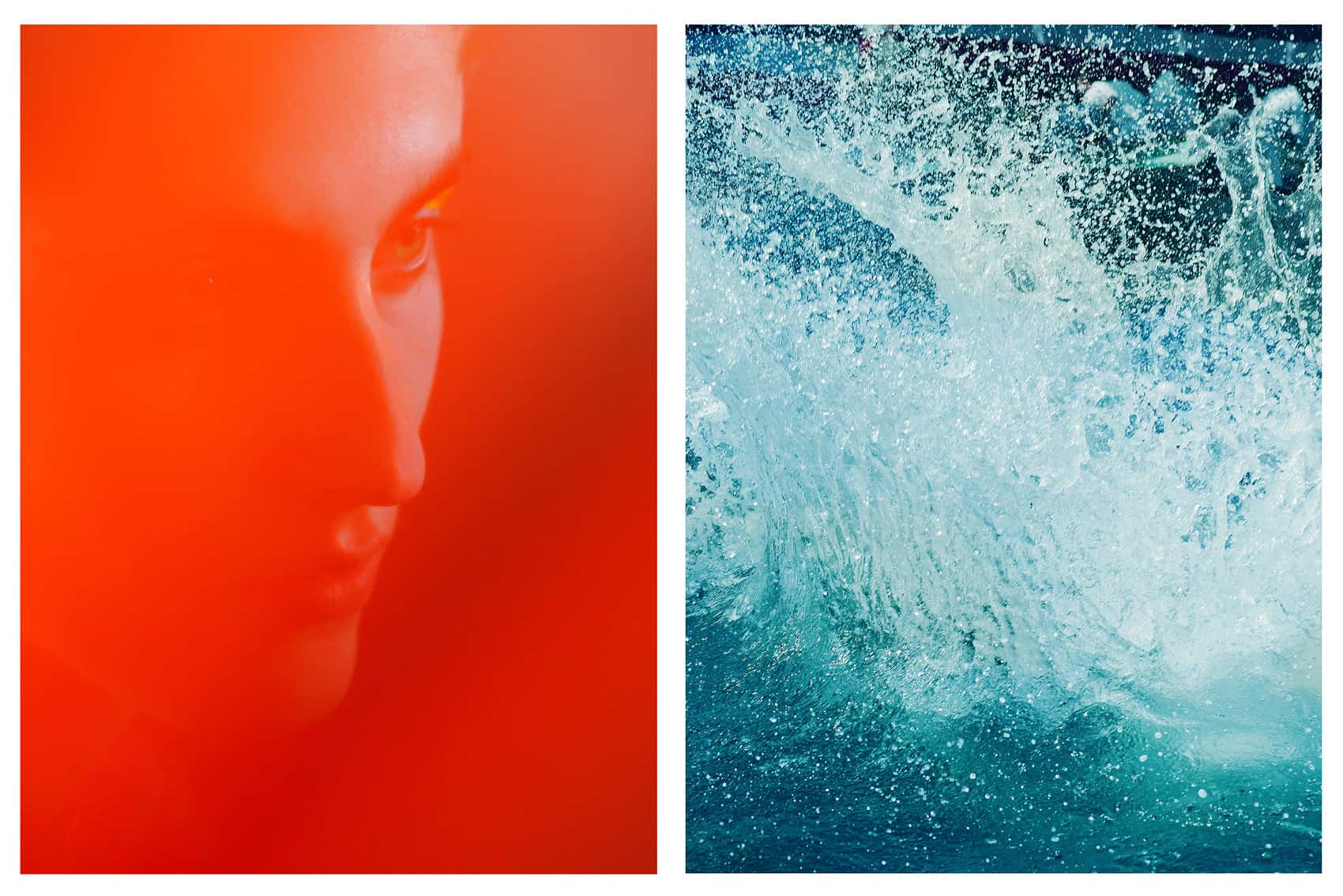

From Stump – Christopher Anderson

Are you constantly taking in the work of other photographers?

Yeah, less and less so as an immediate influence, I guess, because the more I do this, the more I’m trying desperately to remove the filters of other photographers and see it in an honest and pure way that is my own, and to internalize whatever references that I’ve had, both conscious and unconscious over the years, and turn around and produce something that is genuinely me. So in that sense, less and less. But of course, I still look at photography, and I still enjoy to look at other photography, but I probably…I look at it less and less with the sense of amazement that I did before. I know a lot of the tricks now, which makes me less and less interested in that. The photography that I tend to gravitate to tends to be something that is more simple and generally comes from the heart. Which, by the way, is also the same thing I listen to in music or reading literature or looking at a painting, or any other art. I tend to be more attracted to art that felt like it was screamed or shouted, rather than was mapped out with a calculator.

Hahahhaa, yeah. In interviews you talk a lot about truth, and seeking that…when did you hone in on that for yourself as your work? As the target of the work you wanted to make?

It was…well, I remember after…if you’ve done research, you know about the story I did many years ago, where I took a boat trip with people trying to reach the United States, and we sank, and then we were saved, long story short. There was a moment when I was photographing, when we honestly thought that we were not going to make it. I assumed that the pictures that I was making were going to die with me. And for a long time after this, reflecting on this moment of, “why make pictures that won’t exist? What was the point of photographing in that moment?” That was the earliest moment where I had this realization of understanding the reason that I made pictures then had something to do with trying to explain something to myself, and it was through that, knowing at that moment that what I wanted my pictures to do was to communicate that experience.

It was not to explain anything, it was not to…dazzle anyone with the “fireworks” of photography, but to make you feel something, that hopefully this emotion could be left on the print that would make someone feel something. I think that was the earliest moment where I had this true sense of, “ah-ha, I know what I’m after! And that’s what I’m gonna go for.”

How did you, in those early days after that experience, how did you go about accomplishing that in your photography?

That is the part I’m not sure that I can really articulate. That’s where words kind of stop functioning well for photography. It was about just wanting to see in a more instinctive way, and to see things through the camera instinctively and emotionally and to really react with my gut to what I was seeing rather than try to make nice pictures. I do a lot of teaching, and that’s often what I try to communicate to students, is to quit trying to make nice pictures and start trying to see something. I know that sounds like a bunch of hocus pocus or hippy dippy stuff…

It’s art, man.

I can’t describe it any better than that, I really wanted it to be…intensely, instinctually, gut-level connected to what I was photographing.

Right, more…reflexive than consciously motivated.

Yep. More heart, less brain. Like I said, one of the things that drives me nuts is academic photography, I don’t connect to it at all, I don’t understand…I don’t want to piss people off, but that to me misses the point of what photography is. If it takes an explanation, that’s when you’ve totally lost me.

Do you think you would have chafed studying photography at a more academic setting?

I don’t know. I sometimes regret the fact that I don’t have an academic foundation for which to hate it, hahahahaha!

Hahahaha!

But yeah, sometimes I think it would be nice to have a better academic background for it. But…I don’t know how that would have changed me. Maybe I would be doing the same thing I am now, maybe it would have crushed my interests, I don’t know, I really can’t tell. Sometimes I think, “wouldn’t it have been nice to have been in school studying photography, that sounds kind of fun!”

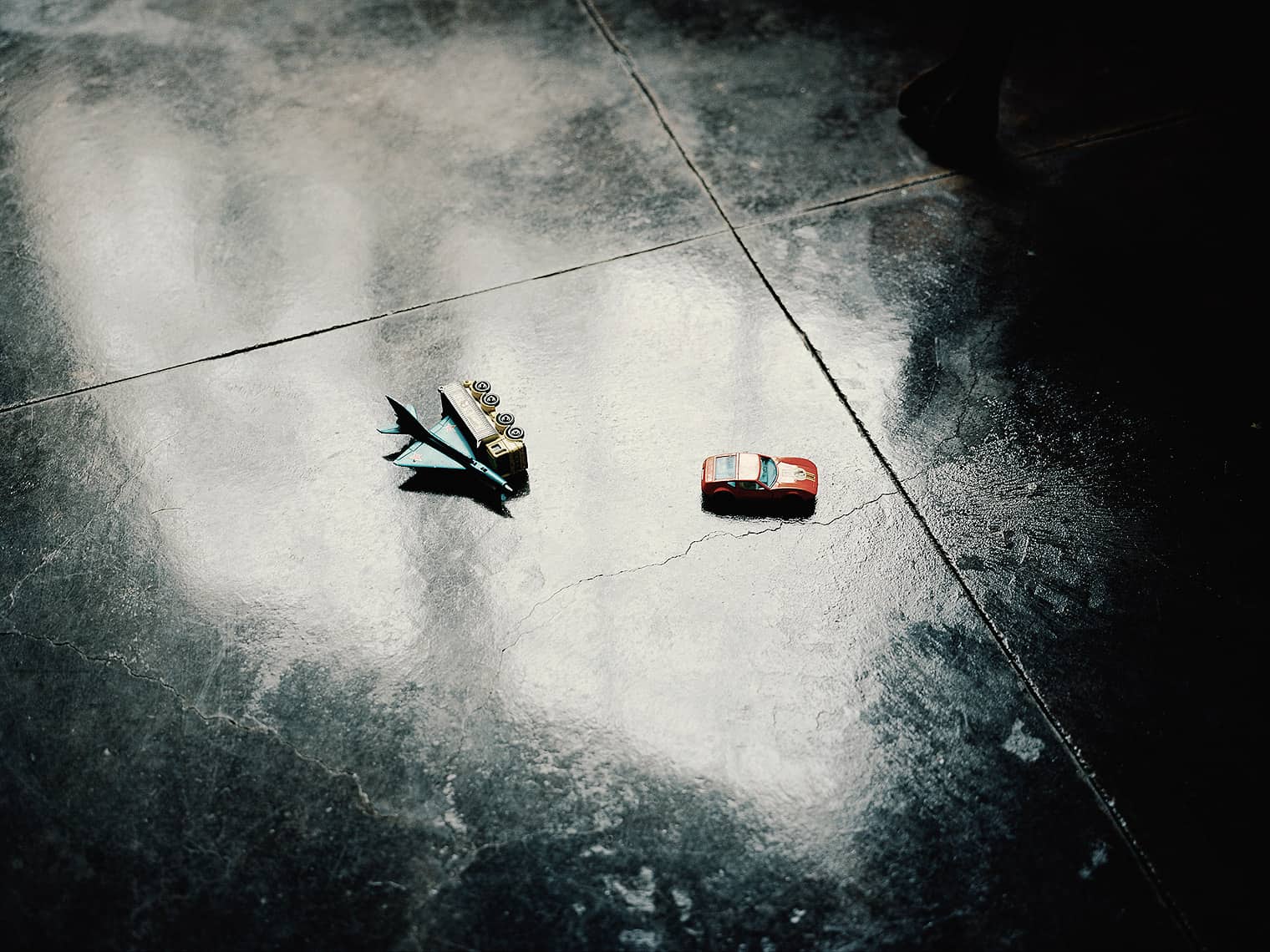

From Son – Christopher Anderson

You mentioned that when you quit conflict work, you’d had a child, but that was not the main reason, that it was trouble reconciling your feelings with conflict photography. What did you mean by that?

Well…I can’t put this into nice tidy sound bites for you because it’s a long involved conversation…

We want long and involved!

We can go forever!

That’s what we want!

Let’s begin with the simple fact that it’s difficult to look at the suffering of others, and to form that into the aesthetic shape that you need it to be. Even though consciously you can say to yourself, “there is a purpose for this, there is a cause that is just…”

We spoke to Ron Haviv last year about this similar thing, where, for him, it’s definitely a cause.

Yeah. Ron is one of the rare people who can say his pictures actually made a visible difference in the world. His pictures arguably helped stop the Bosnian war. I can’t say anything like that. I hope that perhaps my pictures will be valuable for history in some way, or for the record or whatever. But you start right there, this is a difficult thing to do, even when you tell yourself you have a reason for doing it. I know Ron, so I know that even for Ron, it is a difficult thing to reconcile. But you can still get beyond that and do your job and do what you need to do. But then there’s something else, that for me runs deeper, in just the idea, the myth of objective photography all together. The whole…there’s a certain…oh no I’m going to head into some bad territory, hahahahaha!

Hahahha!

There’s a myth of objectivity that I don’t believe in. And it became more and more apparent to me that what I was doing was not objective journalism, that what I was doing, in order for it to be any good at all, had to be totally subjective.

Sure.

My function, I realized, was as an editorial columnist, not a news reporter. I was giving my opinion and it was clear that this is my opinion. But there’s also these…lines are so blurred in photography, where they’re pretty distinct in journalism, where on the editorial page you have that, and on the other pages you have the news. But my editorial pictures were appearing in the news section. And there’s also this idea that, more and more with this World Press-style of photography, this hyperbolic drama, this melodramatic thing that is infused in photography that’s not real, not true.

I had a harder and harder time reconciling that and realized, because the kinds of pictures that I take, playing with this line of what is factual and what is true, I want my pictures to be true, knowing they cannot be factual. But then we get into the debate of what is fact or fiction, but what I mean by that is, in the sense I don’t believe in facts…we all see the same event a different way. That doesn’t mean that the way we see it isn’t true, but we will all bring different facts to it.

True.

So I want to be committed to truth, which has something to do with honesty. And that often gets confused, and sort of the documentary photojournalistic world press view of what photography is.

When you decided that for yourself, what steps did you take to move into the current kind of sphere you’re in now?

My book, CAPITOLIO, about Venezuela, it was about many things, but part of the thesis of this book was a questioning of this very idea of objectivity and subjectivity. And questioning the idea of photojournalism, which was my roots. To me, in many ways, that book was sort of the demarcation line of when I broke away from that idea, and was sort of my statement on objectivity in photojournalism. The visual language that is used is black and white, melodramatic, photojournalism kind of thing. But the book is constructed in a way that is really ambiguous and is kind of confusing, in terms of information.

It actually works against the very idea of journalism casting light on something, because what I wanted to get at was something more, the area of confusion where I’m saying, “hey, I don’t really understand what’s going on at all, and I’m feeling these sorts of things, and I’m feeling this sort of thing, and the people I meet are experiencing this sort of thing. But to tell you what happened today? I don’t know.” And then following that, my book, SON, which was in other ways much more journalistic, because I wasn’t saying anything.

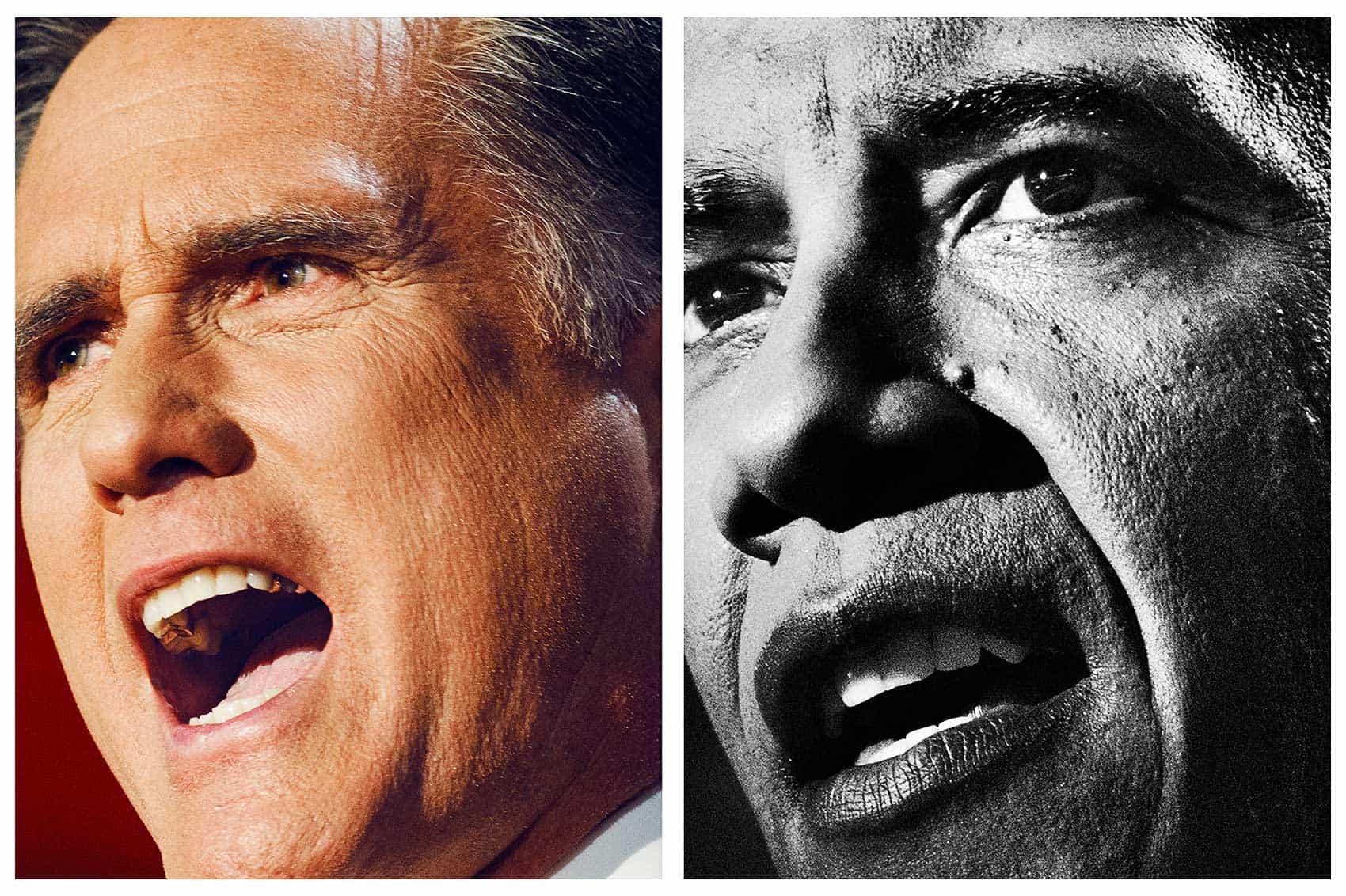

From CAPITOLIO – Christopher Anderson

Because you had no agenda, yeah.

No agenda, I wasn’t reporting on anything. I wasn’t making pictures that were about anything at all, they were my very immediate, very personal reflections on my own life.

Right.

I wasn’t going off to Afghanistan to report on something someone else was going through, this was just like me holding up a mirror and saying, “this is what is going on.”

That sounds very similar to how you felt about the Haitian boat ride, that it’s very immediate, very in the moment, very expressive.

Exactly. That’s why I said at the beginning of this, that to me, this has all been a very natural progression. It’s all been an organic, “this lead to this lead to this” and they’re all connected. You see my portraiture work now, in my mind, even though it may look very different than pictures on the Haitian boat, I’d like to think the cohesive thing is that you still feel my presence, you still feel me looking at the subject, and you still feel me saying something about the subject. Does that make sense?

Definitely does, definitely does. I mean, the way I’ve always thought of photography is that, the people who are best at it, you see them in every photo they take. Their point of view, their visual language is so potent within each image; it’s instant, the recognition is instant.

And that’s the only thing to me that’s interesting in photography, is seeing through someone else’s eyes. This chance that, I tell students a lot this, that movie Being John Malkovich, where they get off at floor 13½, or whatever it is, 7½?

7 ½, yeah.

7½ floor, and they go into a room and get to see through John Malkovich’s eyes, that’s photography. A pretty picture? I’ve seen all the pretty pictures. An academic study on this or that? To read about it is fine for me, I don’t need to see the picture that results from it. But getting that chance to look through someone’s eyes and see the way their brain looks at something and makes that connect? That’s what gives me chills, that’s what puts goose bumps on my arms. That emotional quality of photography, that’s interesting, everything else is a trick, it’s a party trick. Put a light here, I can do this, I can create some kind of artist statement about this notion that I’ve reflected on, which I’ve chosen to do…all of that’s a party trick, I want to be punched in the gut.

Totally. So, did yours books help facilitate you getting more of the commercial work?

Yeah, the commercial work is really weird and a fairly recent phenomenon. A lot of that was, I would have to say, the collaboration I did with New York Magazine for a few years. I think that helped lead a lot to more commercial work, just because, by the very nature of constantly doing this collaboration with the magazine, I wound up photographing many things that I wouldn’t otherwise photograph, in ways that I wouldn’t otherwise photograph something, which linked itself to a commercial translation, I think.

How did you end up with that Photographer In Residence gig?

Well, that came out of a long collaboration with Jody Quan, the director of photography at New York Magazine, and Adam Moss, the Editor-in-Chief of the magazine. Both of whom I’ve worked with at New York Magazine, and The New York Times Magazine, for ten years before that. And I’d photographed a wide range of subject matter with them, many different stories; from portraiture to Haiti boats. The conversation came up with them about doing a collaboration in order to create a series of portfolios and bring out a certain visual voice to the magazine, I guess, that made sense for them and made sense for me, and was an extremely thrilling creative experiment in collaboration with that.

Are you no longer the photographer in residence?

CA: No, not since April of last year. I’m no longer doing it. I’m still working with New York Magazine, just not under those terms, which kept me as an editorial exclusive to the magazine, so now I’m dating again, as they say, hahahahaha!

Ha!

And maybe that has made sense for commercial clients, the fact that I have a background in doing portraiture and documentary type work, and I’d like to think that my history as a photographer is able to inform my commercial work. So I hadn’t pursued a lot of commercial work until relatively recently. I was busy doing my other things, now I’m paying for a family more.

But it sounds like, where, for some people, they might lament not being able to do different work, for you, the problem solving, the challenge, the…seeking the heart of your subject, it doesn’t really matter what sphere of photography you’re in, your goals are the same?

Let me rephrase your question.

Please!

What I think you might be asking, is do I miss what I did before?

It sounds like you don’t miss it!

And the answer is, no. Not any more than I miss being twenty-five years old and doing the things that I was did when I was twenty-five. Yeah, sometimes it would be nice to be young and do that again again, but I don’t miss it in the way that it means that I’m not enjoying where I’m at now. In other ways, it was different phases of life, those were more about a moment of discovery, and now it’s like a moment of doing other things; I’m taken into different creative directions now.

There’s still discovery within your work.

Yeah, there’s still discovery. In that organic, natural progression, I’m having the time of my life right now, I’m very much enjoying being engaged in a different creative way than I was then, or different subject matter maybe? But no, I don’t long for, or regret that I’ve changed gears, or shifted from doing that.

This feels like…what photographers should go after, at a certain point. Conflict work seems, for the most part, Ron Haviv excepted, a younger person’s game. Whereas you’re older, you want different things from your work.

Yeah, and there’s also the idea that, I think I’ve said all that I personally can say about war.

Right.

I don’t have any more to say about that. And when you start repeating yourself, especially with difficult subject matter…there’s already the question of how do you go then and photograph this person suffering, and it’s a situation that you’ve seen before, many many times, and you realize it’s a picture you’ve made many times, so what are you doing then, at that point? Other people may find their ways to reconcile that. Many of my friends do. Me, personally, I couldn’t. I could no longer keep up with that.

Did you notice a psychic toll being taken?

Oh yeah, yeah. And in many ways, it has taken that toll. I’m still…suffering is the wrong word…I’m still injured from that. It’s a hard thing to, do day in and day out, for too many years.

Yeah, definitely.

And it usually doesn’t end well. You get darker and darker, or you get hurt.

So now, in the work you do now, what interests you most about the subjects you’re covering now?

I would say that the same thing that always interests me, which is a sense of humanity.

Because you’re dealing with arguably the second most powerful man in the world at times, you know, like when you photographed Joe Biden.

Joe Biden, yeah, yeah. Even there I’m looking for a sense of humanity, or lack thereof! In Joe’s case, there’s a lot of humanity, I like the guy. But politicians in general…you know. I’m looking at a certain sense of humanity, looking for the poetry in life, I guess. That thing, that emotional quality of photography that says something about our experience.

Do you have any favorites from these past few years? Ones that really stuck out for you?

The only thing I can remember are the pictures of my kids, ahahaha!

That’s a fine answer!

No, I mean, past few years…I tend to think, when I think of my pictures, in terms of the book, because the book is the culmination of the work, it is the ultimate form that I want to see the work in, how I want to use the work. So of course when I think of recent works, I think of my last couple of books. Like Stump, and Son, and the one that I’m working on right now, which has a lot to do with France, and French identity. I know it seems weird, my children happen to be French so…

Makes perfect sense!

And it’s a place I’ve photographed a lot. So that’s the book I’m working on now, I’m actually laying it out and doing the editing right now, not sure when it will be out. But the current project is the one that I seem to think of most fondly of, so when I think of pictures right now, it’s that.

Do you have a particular through line, thematically, to this France project?

It’s a book that is about…you know, it’s a strange time in France for many many reasons, some of which we all are pretty well aware of at this moment, which is linked to other different ideas of what it means to be French these days, which is also a question that a lot of Europe is dealing with, what it means to be a European; German, French, Belgian, or whatever. Which is also a theme that the United States deals with, what it means to be American.

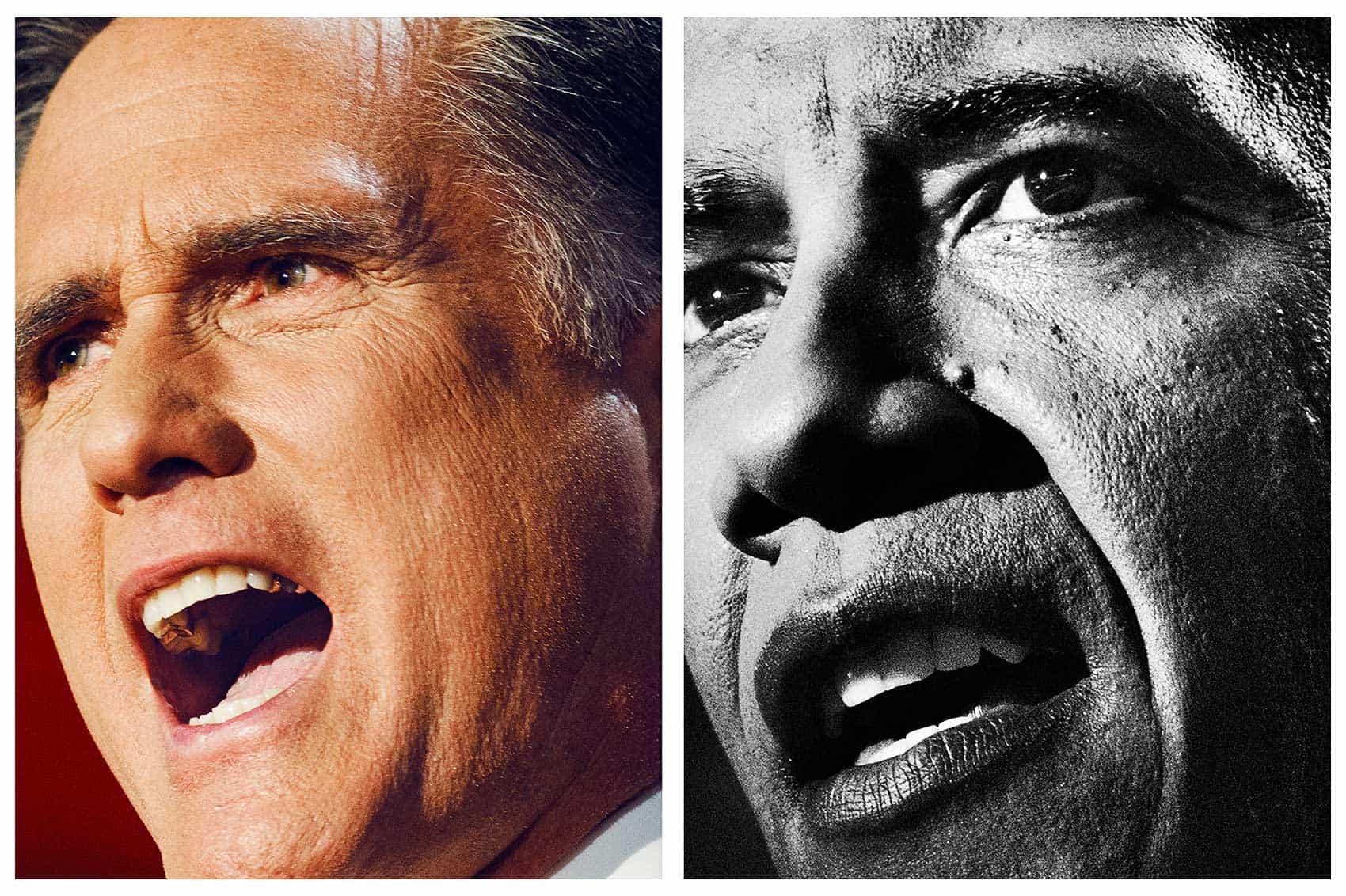

From Blue Blanc Rouge – Christopher Anderson

National identity.

National identity, I’m even scared to say that I’m making a book that deals with race, because it feels pretty pretentious to say that.

I think race is important!

I’m saying, for me to say, “I’m making a book about race!”

I say go for it!

I’m not making a book really about anything. But I guess the pictures touch on ideas of identity and nationalism, and even race, and many things about this idea of where France is at the moment.

Are you seeing things bubble up that you hadn’t realized during the picture-taking portion of this project?

No, unfortunately just the opposite. I never foresaw that things as bad as what has happened recently would happen, but yeah, I started the book with this idea. I started making the pictures with this idea that there are dark days ahead.

When it comes to books, because I’d seen you mention focusing on books more…when you laid out your first book, you said it was filmic,…there seemed to be notions of controlling how fast and how well people took in the images. With this book, do you have that kind of thing in mind, when I heard you talk about that book, it reminded me of comic books, in that, depending on how the images are sequenced and sized, and you can control time in a way.

That is a great analogy that I’ve never used before!

It’s all yours!

That’s what I was trying to play with, with that book. I was doing a lot of experimentation with the limitations of the medium, of the book form, in terms of their connection to cinema and, without even thinking about it, yeah comic book style pacing, timing, a sense of movement, a sense of forward movement.

I think in all of my books, I’ve used that to some degree, not as consciously as that book, where I was really really intent on trying to put cinema on paper. But I think my books are always…certainly Son and Stump both have a certain flow where they’re intended to be read from front to back.

Right.

Rather than just being a collection of nice pictures, there really is a sense of beginning, middle, and end. And this one is no different, as I’m laying it out now. I’m doing a lot more playing with diptychs, and I guess I’ve always done that!

There’s definitely an element of that in Stump.

Yep, it’s always been in my work! This one is really about the diptychs, but then I think Stump was definitely that, too. So, it’s very similar to that, is that I’m more interested in how pictures work together and the meaning that they can build out of that.

The dialogue between images.

Yeah. So there’s a lot of that, there’s the pacing of beginning, middle, and end, but no, it’s not the same direct cinematic structure that CAPITOLIO had. Although, yeah, I think that I’m largely influence by cinema, and that always plays a role in how I think of books, and think of constructing books.

Are there particular filmmakers that you’re drawn to?

Now you’re going to put me on the spot!

It’s what we do here at TPJ.

Anything with a car chase, hahahahaha!

Love a good car chase!

Love a good car chase!

Ronin, you ever see Ronin?

It’s the one I always think of! Exactly!

Ah, I love that film.

You know, filmmakers that I’m influenced by, it’s hard to make a direct connection, but Kubrick is probably, in many ways, the way my bodies of work seem so different, and the way his films seem to be…

Always different subject matter, yeah. But his sensibility is the same, throughout.

Sensibility is the same even though, like, Doctor Strangelove is comic, it was funny, and The Shining is more horror film. But yeah, good car chases.

Now, a question we ask of all our subjects: do you prefer the process or the result, when it comes to photography?

Hmm, I really don’t know how to answer that, because I love them both for different reasons. I guess I would have to say the process, because the pleasure from the results seems so short-lived these days. I see the printer, I see the book, and I’m onto the next thing already. The process, for me, can be part of meeting wonderful people, interesting people, seeing amazing things.

But there’s the other part of the process, the accounting…because when I think of the process, people think my life is romantic, I just wander around and take pictures, but no, I do my taxes. I have to do administrative work, I’m sitting there, cleaning the spots off of photographs, that kind of stuff I don’t enjoy at all. So man, I can’t give you a good sound bite answer.

No, again, we don’t need sound bites. We want truth.

Haha, truth!

I seek Knowledge, and its bastard son, Truth. That’s my personal motto.

Hahahahhaha!

One thing we haven’t really touched on a lot, is what you kind of alluded to here, the business aspect. Having been in the industry for a good number of years, what kind of changes have you observed in the industry? That have affected you the most?

Well, I used to be able to make my living as a documentary photographer, and that’s impossible these days, so that’s affected me. That was a profession, being a conflict photographer, or documentary photographer, whatever you want to call it. It was a profession that somebody had, and you made a living, and there were magazines to support that industry, or other ways. Now, that kind of doesn’t exist anymore.

And then the other sheer fact of being just absolutely inundated with images. I feel like I’m standing in an avalanche path of images. And how to make an image that stands the test of time and rises above all that noise out there and cuts through it to actually reach people. It still shocks me that an image of mine can sometimes do that. That happens, and it amazes me.

Does it actually feel harder these days to take an image you’re happy with?

Oh I’m not talking about pictures I’m happy with, I take pictures that I’m happy with, when I take a picture that I feel is an honest reflection of my experience, I’m happy.

Okay, yeah.

But how to take a picture that cuts through that noise, that is the challenging thing. That is harder than ever, because the sheer number of images out there. That’s the big change, and I can’t imagine…thinking back now, what if I were starting out, and being a young photographer, how daunting that must seem? Not even the “how do I get my work out there” part of it, because any person that’s good enough with self-promotion is going to figure that out. It’s more about “how do I make images that get into peoples minds, but beyond the noise? How do I make an image that people will remember years from now, that will be the image that filters through all the stuff.” And that would seem absolutely terrifying right now for a beginning photographer.

I’m fortunate now, I’ve had a bit of a career behind me, and have been published in magazines and pictures have been seen, and nice people like you have interviewed me and put me on the web, so I’ve kind of had avenues to get work seen, in a way, but I can’t imagine starting right now at zero, like, how to even make a picture that someone is going to remember, that’s going to mean something ten years from now, twenty years from now. I don’t mean to depress all your readers.

It is a common refrain from our more experienced interview subjects.

But yeah, if there’s one thing that’s on my mind other than trying to be honest in what I’m doing, is how to make pictures that will stand the test of time, that’s the constant challenge, I guess.

And you’re still represented by Magnum?

Yes.

How has that been for you, professionally?

Well, its been my home and my family, I’m sure it helps to open some doors that have nothing to do with me, that are just because I have Magnum attached to my name, which is a very useful, fortunate thing. It’s also a maddening place, a dysfunctional place in some ways, and a beautiful and human place in other ways. I still pinch myself whenever I get to sit down next to someone like Josef Koudelka or Elliott Erwitt and have a conversation with them, I still can’t, to this day, believe that I get to do that. To get to learn from my colleagues and be motivated by them and inspired by them, is a pretty fortunate thing.

Do you have a lot of photographer friends? When you’re not working, do you want to distance yourself from the work? Or is it something you immerse yourself in constantly?

My closest friends are photographers, and we don’t really talk about photography together…that’s not true, we do. Yeah, I’m surrounded by photographers, that’s the nature of being in a photo ghetto, I guess. But yeah, I…talking about photography is boring? I guess, yeah. Photography and the photography industry, the photography industry talking about photography, and sort of the staring at our navels aspect of the photography industry, I find really boring. But I’m surrounded by photographers, inevitably it comes up, but I’m much more interested in talking with them about life or car chases in movies.

Hahaha. Does the equipment interest you at all that you use? Or is it just different tools for different jobs?

Just different tools, yeah. I experiment a lot with stuff, I have lots of conversations with people about it, because you’re totally right. I grew up building fences and working construction, and having the perfect hammer was really important to me. Same with photography, I spent a lot of time getting the right tool, but it’s not interesting to me at all. Especially when it comes to the photography itself, when I look at photography, I don’t want to be aware of the presence of a camera.

Ah, mhmm.

I don’t want to be reminded of the process of photography, I want to be transported somewhere else. And whenever I’m aware in any way of the process or the equipment, or the tricks of photography, is usually immediately when I’m turned off by a picture. That’s the moment in the film when the boom mic comes in.

And then, an audience question. The friend of mine who actually put me on to you was very curious, they were wondering are you fully digital now?

Yes! Yep.

Was there any kind of issue with that, for you?

It’s only recently that I admitted that to myself, because I still had film cameras, and I still think, “oh yeah, I’m doing this digital right now for the job, but I’m a film photographer!” And then I realized that I hadn’t picked up my film cameras in a couple years. But beyond that too, film is nostalgic, I love film, film is beautiful, don’t get me wrong. And in certain ways, it’s more beautiful than digital, and of course, I try to achieve a certain color palette, filmic color palette in my digital, etc etc. But there’s a certain nostalgic quality that I’m trying to escape. I don’t want to look back. I don’t want people to like my pictures because it looks like they could have been made in the seventies.

I want to be here in the present, in the here and now. The masters that inspired me who shot on film, I kind of think that if they were photographing now, they would be using digital because it is the medium of today. Henri Cartier-Bresson took the small camera, and said, “oh let’s see what we can do with this small camera, and how does that change what we’re seeing in photography today.” I kind of think the same way now, like, “how does digital affect that?” I don’t have the answer for that, but I’m more interested in pushing the medium that is of my generation rather than nostalgically holding on or going back to something from before. And I’m very aware that it dates me now, because nowadays, it actually means you’re an old guy if you’re shooting digital. All the hipster kids, I know all the hipster kids, my interns and assistants, they’re all shooting film, I know that. Being the guy shooting digital makes me the old guy!

I hadn’t thought about it that way! Speaking of your interns and students, what was it that brought you to teaching?

Teaching is interesting because in order to teach, you have to be able to articulate what it is that you do. And in order to articulate what it is you do, you have to understand what you do. So teaching, actually, was very rewarding for me, because it forced me to examine and understand myself. And to put questions to myself, very basic ones, like, “why do I photograph? What does a photograph mean to me?” Which, in my work, is the starting point for knowing who I am, because that’s what the pictures are about, the pictures are about me, so it starts with knowing yourself.

What kind of things did you end up teaching? Was it a workshop? In what environment were you teaching?

Workshops usually, yeah.

What was the theme of the workshop?

Usually my workshops tend to be about finding your voice. Which is all about knowing who you are.

So you’re teaching them what you have discovered through the act of teaching?

No, hahaha, I think I’m teaching them that it’s important to find out who they are on their own. I’m teaching them that I won’t be able to teach them anything, they’ll have to figure it all out!

But it takes eight hours a day to teach them that.

Exactly, it’s a journey.